Le tombeau d'Edgar Poe

Tel qu’en lui-même enfin l’éternité le change,

Le Poëte suscite avec un glaive nu

Son siècle épouvanté de n’avoir pas connu

Que la mort triomphait dans cette voix étrange !

Eux, comme un vil sursaut d’hydre oyant jadis l’ange

Donner un sens plus pur aux mots de la tribu

Proclamèrent très haut le sortilège bu

Dans le flot sans honneur de quelque noir mélange.

Du sol et de la nue hostiles, ô grief !

Si notre idée avec ne sculpte un bas-relief

Dont la tombe de Poe éblouissante s’orne,

Calme bloc ici-bas chu d’un désastre obscur,

Que ce granit du moins montre à jamais sa borne

Aux noirs vols du Blasphème épars dans le futur.

- Stéphane Mallarmé (1887)

I thought I'd start off my discussion of the recent Netflix movie The Pale Blue Eye - which I very much enjoyed, in case anyone's wondering - by quoting Mallarmé's immortal poem "The Tomb of Edgar Poe."

I was going to add a literal translation of it, but then I ran across the one below, by American poet Richard Wilbur, which it's hard to imagine improving on:

The Tomb of Edgar Poe

Changed by eternity to Himself at last,

The Poet, with the bare blade of his mind,

Thrusts at a century which had not divined

Death's victory in his voice, and is aghast.

Aroused like some vile hydra of the past

When an angel proffered pure words to mankind,

Men swore that drunken squalor lay behind

His magic potions and the spells he cast.

The wars of earth and heaven - O endless grief!

If we cannot sculpt from them a bas-relief

To ornament the dazzling tomb of Poe,

Calm block here fallen from some far disaster,

Then let this boundary stone at least say no

To the dark flights of Blasphemy hereafter.

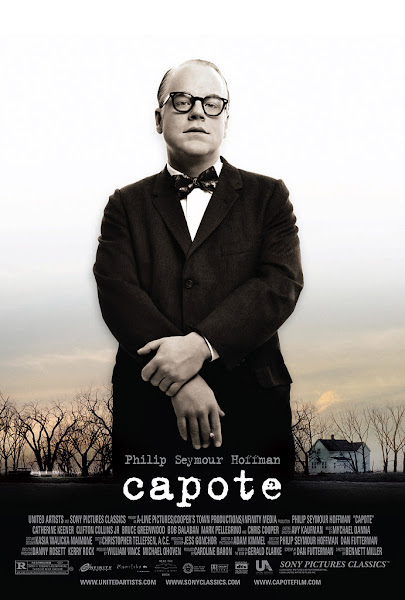

Is it just me, or do you see some resemblance between the whiskery face of France's greatest symbolist poet and that of Christian Bale, above, in his role as "Landor" in the movie?

Mallarmé's implication that it is poets who are meant to give "a purer sense to the words of the tribe" [Donner un sens plus pur aux mots de la tribu] lies at the heart of Modernist aesthetics. It ranks with Baudelaire - another Poe fanatic - and his view of the poet as a wave-riding albatross, expounded in his verse of the same name:

Le Poète est semblable au prince des nuées

Qui hante la tempête et se rit de l'archer;

Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,

Ses ailes de géant l'empêchent de marcher.

The Poet is like that wild inheritor of the cloud,(The translation, this time, is by George Dillon, Edna St. Vincent Millay's collaborator in their joint 1936 version of Baudelaire's Flowers of Evil)

A rider of storms, above the range of arrows and slings;

Exiled on earth, at bay amid the jeering crowd,

He cannot walk for his unmanageable wings.

Edgar Allan Poe ... yes, we know all about him (or think we do): the inventor of the detective story; the misunderstood genius, betrayed by the vindictive jealousy of his literary executor, Rufus Griswold, who almost single-handedly constructed the myth of his drunkenness and infamy; the visionary poet, first recognised by the French before the English-language world reluctantly followed their example; and - somewhat surprisingly - once, briefly, a cadet at West Point, where the film is quite correct in placing him.

What then of the Holmes to Poe's Watson, Augustus Landor? Well, the "Augustus" comes, presumably, from Poe's own prototypical detective Auguste Dupin, the protagonist of "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt", and the distinctly Borgesian "Purloined Letter".

As for "Landor", rather than English poet Walter Savage Landor, it seems probable that his surname is meant to refer to the little-known vignette "Landor's Cottage" - the last story Poe ever wrote, in fact - which describes the house he himself was living in at the time. The Landor of the film, too, inhabits a particularly picturesque and bookish cottage.

Mind you, most of this inventiveness must be attributed, not so much to the film-makers as to the author of the novel the movie is based on, Louis Bayard. I'm guessing, like many of us, he found frustrating the inconclusiveness of "Landor's cottage": a long descriptive preamble to a promised story to be told in a next instalment which, alas, was never to appear.

All this trivia aside, I have to admit that I was somewhat surprised to find so lukewarm a response to the movie in a number of quarters. Most of them criticised the film's "implausibility" and "inaction", which struck me as a little perverse, given the prevalence of both factors in Poe's own published writings.

As critics then and now have often failed to grasp, with Romantic artists such as Poe, it's all or nothing: you're in or you're out. If you have a problem with orangutans committing murders or with the propensity of Poe's heroines to get themselves buried alive or have their teeth extracted post-mortem, then you'd better stick to realists like Dickens or Trollope.

Or, in this case, you'd better stick to bad parodies of Agatha Christie, such as the dreadfully tedious and poorly plotted recent whodunit above. I was interested to see that many of those who'd awarded The Pale Blue Eye two or three stars had given See How They Run four or five.

It's not, you understand, that I have a problem with Agatha Christie or the other luminaries of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction in their own right - just with the decision to replay them badly as farce. It does make me realise, though, that in detective films as well as in novels, I'm not really looking for the same things as most aficionados of the genre.

For me, it's all about atmosphere and character. I like the kinds of scenes - so abundant in The Pale Blue Eye - where characters wander around deserted graveyards, or sit in crowded taverns trading witty banter. Best of all are the occasions when large books are taken down from dust-laden shelves and opened to salient passages - translated impromptu, in this case, by Poe himself as Robert Duvall and Christian Bale look on approvingly.

Does any of this advance the plot, or assist us in unmasking the criminal? Not really, no. I don't care. Murders don't really interest me very much - but I do like a picturesque detective, with lots of hidden demons, and a taste for bamboozling even his closest collaborators.

All of this, of course, is anathema to the true devotees of detective fiction. They like an ingenious solution to the mystery, and such curlicues as believable characters or well-painted backdrops are largely irrelevant to them. Hence their preference for the pasteboard mechanics of See How They Run over the ice-bound dramatics of The Pale Blue Eye.

I suppose, in the end, it's best to have both. I did enjoy the original Knives Out, as well as its sequel Glass Onion, I suppose mainly because Daniel Craig was so obviously having the time of his life playing absurd anti-Bond chicken-fried Southerner Benoit Blanc.

There was, as I recall, some kind of a murder being investigated at the time, but I was more interested in watching the characters score points off one another as each of the superannuated stars tried to steal scenes with ever more outrageous business.

Poe, too, could be ridiculous at times (some would say all the time). But he was, in the end, a very serious guy. He felt strongly about the need for rigorous critical judgements in the infancy of American literature, and the hatchet jobs he performed on many of his more celebrated contemporaries were legendary. Funnily enough, many of those authors are now known simply because Poe decided to critique them.

Harry Melling - perhaps better known as Harry Potter's spoilt cousin Dudley Dursley - does an excellent job of animating the touchy, emotional, fiercely intelligent contradiction that was Poe. Some viewers have commented on the incongruity of a Southern accent for someone born in Boston, but Poe did like to portray himself as a Virginian, so this is certainly an arguable quirk to impose on him.

After all, somewhat closer to our own time, Boston Brahmin poet Robert Lowell affected a Southern accent in his own poetry readings - presumably as a salute to his Southern Agrarian mentors John Crowe Ransom and Allen Tate - as you can hear in this recording of his 1964 poem "For the Union Dead".

Talking of poetry, there's been a certain amount of discussion of the verses - allegedly dictated to him by his dead mother - Poe quotes halfway through the movie:

Needless to say, these were not written by Poe - he may have used some dodgy rhymes at times, but I can't see him combining "hurry" with "flurry" and "slurry". Nor is the syntax precise enough for his almost over-controlled style. They do have a pleasing ring in context, though.Down, down, down

Came the hot threshing flurry

Ill at heart, I beseeched her to hurry

Lenore

She forbore the reply

Endless night

Caught her then in its slurry

Shrouding all, but her pale blue eye

Darkest night, black with hell

Charneled fury

Leaving only

The deathly blue eye

His own poem "Lenore", which presumably inspired these lines, is somewhat more conventional in form:

The sweet Lenore hath "gone before," with Hope, that flew besidePresumably the flimmakers also had in mind the narrator's sorrow for "the lost Lenore" in "The Raven":

Leaving thee wild for the dear child that should have been thy bride -

For her, the fair and debonair, that now so lowly lies,

The life upon her yellow hair but not within her eyes -

The life still there, upon her hair - the death upon her eyes.

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow; — vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow — sorrow for the lost Lenore —

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore —

Nameless here for evermore.

Somewhat bewilderingly, Poe has more than one grave. The simple headstone above - with its appropriately superimposed raven - is in Baltimore, Maryland. His remains were, however, disinterred in 1875 to be shifted under the rather more pompous monument below - presumably the one which inspired Mallarmé's poem.

A somewhat less accomplished verse - by an equally distinguished admirer, Alfred, Lord Tennyson - was composed for the occasion:

Fate that once denied him,

And envy that once decried him,

And malice that belied him,

Now cenotaph his fame.

What more need one say? If you love the hothouse atmosphere of Gothic extravagance, thrill to the overblown prose of H. P. Lovecraft or Ray Bradbury's early collection Dark Carnival - why not return to their admitted master, the divinely gifted Mister Poe?

As his literary soulmate and principal French translator Charles Baudelaire put it in an 1864 letter to Théophile Thoré - with, perhaps, a mixture of admiration and chagrin:

The first time I opened a book he had written, I saw with equal measures of horror and fascination, not just the things that I had dreamed of, but actual phrases that I had designed and that he had penned twenty years earlier.One thing's for certain, there will always be a certain region of the imagination identified with Poe's name. If you'd like to explore it further, I strongly recommend a viewing of The Pale Blue Eye.