Way, way back in history, virtually at the dawn of time, I remember hearing a lot of buzz about a brand new TV show about a subversive young punk named Bart. His catch-phrases: "Eat my shorts!," "Ay, caramba!," and "Don't have a cow, man!" were already legendary.

But then I watched the programme.

It didn't take long to work out that Bart's was a mere bit part - along with the saxophone-playing Lisa and the long-suffering Marge. There could be only one hero: the fat, stupid, bigoted paterfamilias Homer.

I couldn't really understand it at first. Why was he the star? The other characters were so much more interesting. Why should he be the sun they all revolved around?

But then I started to grasp it. In the bizarre travesty of "family-friendly" (i.e. thought-hostile) norms which had gradually accreted in American pop culture - first in Hollywood, then Network TV - the change-resistant, ideologically as well as racially conservative white man must ipso facto be at the centre of everything.

The workings of this machine are adroitly analysed in Slavoj Žižek's notorious "Pervert's Guide to Cinema", where he points out the "secret motif" in (for instance) all the key Spielberg movies: "the recovery of the father, of his authority."

Archie Bunker was one of the most successful archetypes of this hero with a thousand faces. Again, at the time, I couldn't work out why the butt of almost all the jokes in the show was gradually humanised and centralised until he, inexorably, assumed the mantle of the whole production (remember Archie Bunker's Place?).

It put me in mind of Toril Moi's celebrated comment (from her 1985 book Sexual/textual Politics) about the oppressed subject "internalising the standards of the aggressor." [1] A character may start as a target for satire (like Archie Bunker's original, Alf Garnett, in the mordant British sit-com Till Death Us Do Part), but then the picture begins to adjust back to normal: and the unwise-at-times but basically loveable head-of-the-family model reasserts itself.

It also reminded me of the infamous 2005 "Monkey Pay-per-View" study, where a group of Macaques turned out to be willing to trade cups of fruit-juice for a chance to look at pictures of attractive, celebrity monkeys. Male macaques wanting to look at sexy females seems normal enough - but monkeys of all genders paying out juice to gaze on the images of powerful males is, I fear, yet another manifestation of this thesis.

Let's not pretend that this is an exclusively American phenomenon. Colin Watson's entertaining analysis of the classic English Crime Story gives some startling data about the kinds of heroes who flourished in Britain between the wars. Take "Sapper"'s protagonist Bulldog Drummond, for instance. Here are a few salient quotes from his merry adventures:

[To an adversary he addresses as "fungus face']: "Only a keen sense of public duty restrains me from plugging you where you sit, you ineffable swine."In the last case, it appears to be their disrespect for officers which weighs more in the balance for Drummond than any other aspect of the Bolshevik creed.

[His idea of a hobby]: "Years ago we had an amusing little show rounding up Communists and other unwashed people of that type. We called ourselves the Black Gang, and it was a great sport while it lasted."

[His views on Russia, "ruled by its clique of homicidal, alien jews"]: "The most frightful gang of murderous-looking cut-throats I've ever seen (officers seem to have no control)."

Prominent leftist poet Cecil Day-Lewis (himself an accomplished detective story writer) referred to Bulldog Drummond as "that unspeakable Public School bully." But, as Colin Watson explains:

... fantasy heroes usually are bullies. They must win, and since their opponents seem to enjoy a monopoly of cunning, sheer physical advantage has to be invoked.It rather puts one in mind of Goering's much-quoted remark: "When I hear the word 'culture', I reach for my revolver." [2]

There was an interesting case reported in the media the other day about a British woman who was "shot dead by her father after a heated argument about Donald Trump." As so often on these occasions, it's the line taken by the defence that's really jaw-dropping. The father, a certain Kris Harrison, explained that:

he owned a Glock 9mm handgun for “home defence” and had received no formal firearms training. He initially denied drinking that day but later admitted consuming a 500ml carton of wine in the morning, though he insisted alcohol did not influence his actions [my emphasis].He further claimed that "he had a conversation about guns with his daughter and she asked to see the gun" - despite never having "discussed his gun ownership with him before."

The sequence of events appears to have been more-or-less as follows: the father got into an argument with his daughter, Lucy Harrison, over the merits of Donald Trump's dismissal without penalty after his conviction for falsifying business records to hide the payment of hush-money to adult film actress Stormy Daniels.

Lucy's boyfriend, Sam Littler, told the court that:

Harrison asked her father: “How would you feel if I was the girl in that situation and I’d been sexually assaulted?”And the father's explanation?

He said Kris replied that it would not upset him much because he had two other daughters living with him. Harrison then ran upstairs, visibly distressed.

Around half an hour later, Kris took his daughter’s hand and led her into his bedroom. Seconds later, a gunshot rang out.

Littler said he rushed in and found Harrison lying on the floor, while her father screamed incoherently.

Police later concluded she died from a gunshot wound to the heart fired at medium range.

"As I lifted the gun to show her I suddenly heard a loud bang. I did not understand what had happened. Lucy immediately fell."Needless to say, "a grand jury in the US ... determined there was insufficient evidence to charge anyone in connection with Lucy Harrison's death."

He told police who attended the scene: "We got it out to have a look and just as I picked it up it just went off."

I mean, don't get me wrong, it may have been an accident. The contention that she "asked to see the gun" sounds a little unlikely, though, given her well-documented abhorrence of firearms. Also, it seems an odd thing to want to do a few minutes before leaving for the airport to fly home.

Back in Britain, at the Cheshire Coroners' Court, matters panned out a little differently:

Coroner Jacqueline Devonish announced that she found Lucy Harrison died due to unlawful killing on the grounds of gross negligence manslaughter.Unfortunately these findings are from a coroner's court and not a criminal court, so have no actual effect on Kris Harrison, "described by the coroner as a functioning alcoholic."

The coroner said: "To shoot her through the chest whilst she was standing would have required him to have been pointing the gun at his daughter, without checking for bullets, and pulling the trigger.

"I find these actions to be reckless."

So just what does a guy have to do to get indicted for manslaugher - let alone murder - in a court in Texas? Maybe if it had been the other way round, and the daughter was the Trump suppporter? I suspect Kris Harrison might well be looking at a bit of jailtime then ...

Given these contradictory responses from two courts in two different countries ("divided by a common language," as George Bernard Shaw once put it), the question remains: Is there something in American culture which particularly lends itself to idealisation of the violent bully?

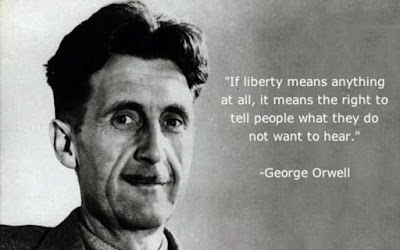

George Orwell certainly thought so. As he said in his classic 1944 essay "Raffles and Miss Blandish":

In America, both in life and fiction, the tendency to tolerate crime, even to admire the criminal so long as he is successful, is very much more marked [than in England]. It is, indeed, ultimately this attitude that has made it possible for crime to flourish upon so huge a scale. Books have been written about Al Capone that are hardly different in tone from the books written about Henry Ford, Stalin, Lord Northcliffe and all the rest of the “log cabin to White House” brigade. And switching back eighty years, one finds Mark Twain adopting much the same attitude towards the disgusting bandit Slade, hero of twenty-eight murders, and towards the Western desperadoes generally. They were successful, they “made good,” therefore he admired them.This may be a little unfair to Mark Twain. Orwell may have read as blind admiration a description originally meant ironically. At this distance in time, it's hard to be sure. Certainly Twain had no time for that bully extraordinaire, the much-hyped "hero" of San Juan Hill, President Theodore Roosevelt.

Here are a few extracts from Matt Seybold's amusing article "The Nastiest Things Mark Twain Said About Teddy Roosevelt":

“[Roosevelt] is naively indifferent to the restraints of duty and even unaware of them; ready to kick the Constitution into the back yard whenever it gets in the way; and whenever he smells a vote, not only is he willing but eager to buy it, give extravagant rates for it and pay the bill not out of his own pocket or the party’s, but out of the nations, by cold pillage.” (February 16, 1905)

“The list of unpresidential things, things hitherto deemed impossible, wholly impossible, measurelessly impossible for a president of the United States to do — is much too long for invoicing here.” (May 29, 1907)

“Mr. Roosevelt is the most formidable disaster that has befallen the country since the Civil War – but the vast mass of the nation loves him, is frantically fond of him, even idolizes him. This is the simple truth. It sounds like a libel upon the intelligence of the human race, but it isn’t; there isn’t any way to libel the intelligence of the human race.” (September 13, 1907)

“Mr. Roosevelt is the Tom Sawyer of the political world of the twentieth century; always showing off; always hunting for a chance to show off; in his frenzied imagination the Great Republic is a vast Barnum circus with him for a clown and the whole world for audience; he would go to Halifax for half a chance to show off, and he would go to hell for a whole one.” (December 2, 1907)

“We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission.” (January 5, 1909)

“Roosevelt is the whole argument for and against, in his own person. He represents what the American gentleman ought not to be, and does it as clearly, intelligibly, and exhaustively as he represents what the American gentleman is. We are by long odds the most ill-mannered nation, civilized or savage, that exists on the planet to-day, and our President stands for us like a colossal monument visible from all the ends of the earth.” (April 3, 1906)

Is it just me, or could one just as easily substitute another recent presidential surname for "Roosevelt" above?

Interestingly, Mark Twain's main theme here seems to be the President's vulgarity and lack of culture. The examples Twain analysed in more detail were mostly instances of "ungentlemanly" disrespect towards women - though he was also unsparing in his denunciations of the hypocrisy and perfidy shown by his countrymen in the brutal annexation of the Philippines.

In conclusion, I guess I'd like to see this set of interesting - to me, at any rate - data-points as a bit more than just another anti-Trump diatribe. Most of those try to present him as something egregious, unprecedented in American - possibly in world - culture.

On the contrary, I'd like to argue that the real problem is that he's so completely typical. Every run-of-the-mill male chauvinist has contributed a little to this particular conundrum. Even in little old New Zealand we have more than our fair share of such consummate asses.

I think that one of the most striking instances of the cult in full cry would have to be the bizarre monologue delivered by Laura Linney at the end of Clint Eastwood's 2003 film Mystic River, where she extols her murderous criminal of a husband, played by Sean Penn, because he is, in her eyes, "a king." The fact that he's just ordered the killing of an old schoolmate, whom he and his gang suspected (wrongly) of having raped Sean Penn's daughter, simply serves to redouble her blind adoration.

We hear the same poisonous slop every day from the grovelling fools surrounding the great Don - even though each of them knows beyond question that they'll be replaced in an instant the moment they cease to genuflect ... and start to question.

Is it his fault they're such spineless jellyfish? No, it's theirs - and ours.

Notes:

1. While I did myself (I think) first encounter "internalising the standards of the aggressor" in Toril Moi's influential book, the actual source of the phrase is Hungarian Psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi. In his 1932 paper "Confusion of the Tongues Between the Adults and the Child," Ferenczi argued that children facing extreme aggression or abuse "survive by internalizing ... the attacker, turning themselves into the object of use, and dissociating from their own feelings." This has a tendency to lead to "self-blame and compliance" to manage trauma.

2. My friend Richard Taylor has reminded me that the quote "When I hear the word 'culture', I reach for my revolver," frequently attributed to Hermann Goering, "actually originates from the play Schlageter by Hanns Johst. The original line from the play is slightly different: "Wenn ich Kultur höre ... entsichere ich meinen Browning!" (When I hear culture, I release the safety catch of my Browning!). This line was performed in 1933 to celebrate Adolf Hitler's birthday and has been misattributed to several prominent Nazis, including Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler."

•