We didn't really intend to make a tradition out of it, but at the beginning of 2022 I posted a piece about finishing a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle called The World of Charles Dickens; then, in 2023, another about completing a new puzzle called The World of Dracula to usher in the New Year:

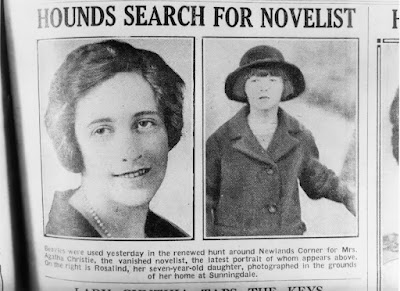

This year, as you'll have gathered from the picture at the head of my post, we have the world of Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot - and here I am starting on the task on (or about) Christmas day:

So why Poirot? I can remember a time when some people adopted a rather sneering attitude towards Agatha Christie. Not a real author, they said (whatever that means) - a mere hack, a penny-a-line writer with no real sense of style of atmosphere.

She was contrasted adversely with more self-consciously literary crime writers such as Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton - wordsmiths for whom detective fiction was simply a day-job, a way to finance their more artistic endeavours. How absurd - and patronising - all that sounds now!

I guess what did it for me - and, no doubt, for many others - was David Suchet's superlative interpretation of the character in the wonderfully entertaining British TV show Poirot, which ran for a quarter of a century, from 1989 to 2013.

I'd read a number of the books as a teenager (my father had a huge collection of them upstairs jammed onto an old wire display frame he'd liberated from a local stationery shop which was going out of business; it made a horrible graunching sound when you swung it around, so we always referred to it as 'the squeaker' ...)

I, however, I tended to prefer such stand-alone mysteries as Crooked House (1949) and The Hound of Death (1933) to what seemed to me then the more predictable puzzles of Poirot and Miss Marple (let alone the egregious Tommy and Tuppence).

I did enjoy Albert Finney's interpretation of Poirot in the original 1974 movie, and (to a somewhat lesser extent) that of Peter Ustinov in Death on the Nile (1978) and its successors. David Suchet took the character in an entirely new direction, though: away from slapstick to the intensely serious world Poirot himself inhabits.

It's not that the Suchet Poirot isn't funny - it's just that he himself is completely unaware of the fact. Ustinov, in particular, tended to play to the audience on the other side of the camera. Suchet never does that.

Which leads us to the vexed question of Kenneth Branagh's Poirot trilogy (if it actually is a trilogy, that is - there seems little reason for him to stop at three if they're still pulling in audiences). There's no question that they're all sumptuous-looking films, with dazzling casts of A-listers.

They are awfully gloomy, though. Branagh's Poirot is constantly castigating himself for various crimes of omission (and commission), and large slabs of invented biography - his First World War service, for instance - have been rather awkwardly shoehorned into the original plots.

It's hard not to admire the durability of stories which continue to invite this kind of reappraisal and reinvention so many years after they were written, though. The ingenuity and originality of Agatha Christie's plots continues to astonish after all this time. She was, it seems, constantly being castigated for offending against the spirit (if not the letter) of the oath sworn solemnly by members of the Detection Club:

Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition , Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence or Act of God?It was Monsignor Ronald Knox who codified these rules into a set of Ten Commandments (or Decalogue) for detective writers:

- The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.

- All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

- Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

- No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

- No Chinaman must figure in the story.

- No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

- The detective himself must not commit the crime.

- The detective is bound to declare any clues which he may discover.

- The "sidekick" of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any thoughts which pass through his mind: his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

- Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

In any case, as the proverb has it, "the dogs bark, but the caravan moves on.' Whatever your opinion of Branagh's own innovations, the result is certainly very watchable, if a little too self-consciously Orson-Wellesian at times. In any case, it's very much in the spirit of other modern adaptations of Christie. Such films as Crooked House (2017) and And Then There Were None (2015) showed that there was still lots of room for manoeuvre in these old tales.

For me, The ABC Murders (2018) went a step too far. John Malkovich's portrayal of Poirot as an aging loser suffering from depression at his failing powers was certainly original, but not precisely enchanting - if that's the right word. The joy and zest of Christie's story was lost in a morass of self-pity (together with a truly awful performance by Rupert Grint as a grim and humourless young police detective). But no doubt the book will survive it, and go on into further incarnations in the future ...

That is, if the Agatha Christie Estate can be dissuaded from rewriting all her old books in line with modern sensibilities. It's not that it's not shocking to come across the "n-" word in the original title of And Then There Were None, and the offensively racist and misogynist attitudes of many of Christie's characters might well be a stumbling block to some readers (as they are in that throwaway remark about "Chinamen" in Knox's Decalogue, quoted above).

But Bowdlerising Shakespeare doesn't seem to have done much good in the long run: except to illustrate the absurdity of rewriting an author to fit a completely different cultural context. One of the many reasons we read is to learn about the past: how people lived, how they thought. If we try to recast them in our own (surely equally flawed?) image, then all we're really doing is adding another wing to our own hall of mirrors.

No comments:

Post a Comment