by Bronwyn Lloyd

[Stella Benson: Self-portrait]Part One: Hyde & Benson

[Stella Benson: Self-portrait]Part One: Hyde & BensonIn a letter written by Robin Hyde in 1935 to her editor friend John Schroder, Hyde made the following declaration:

John, I'd rather be Stella Benson than anyone else in the world. [1]

The following year another of Hyde's friends, Allan Irvine, recorded in his notebook a similar sentiment expressed by Hyde during his visit to the Wilkinson home on 2 December 1936:

Stella Benson is the woman in modern letters whom I’d like to be like. [2]

Time and again within Robin Hyde's correspondence, essays, and literary reviews English writer Stella Benson (1892-1933) was singled out for special attention. Hyde proclaimed Benson as one of the twentieth century's four great women writers; as an unsung genius; as one of a group of modern writers who showed the way forward; as a writer who demonstrated humour, courage, and unstriving humanity.

Hyde also predicted a long life for Stella Benson's work beyond the imagination of her small but devoted following of readers:

Stella Benson's public may be comparatively small, but it will be steadfast for the next twenty years at least, and if she gets her dues, for far longer. [3]

Time has not confirmed Robin Hyde's high estimation of Stella Benson's achievement as a writer, nor the longevity she expected for Benson's work. Benson is a writer who did not receive her dues and who has all but disappeared into literary obscurity. None of Stella Benson's books are in print today; the last reprint of her 1931 novel

Tobit Transplanted, which won the

Fémina-Vie Heureuse Prize and the silver medal of the Royal Society of Literature, was published in America in 1972 under the variant title

The Far-Away Bride.

Stella Benson's absence from the literary canon, however, should not be seen as an indictment of her ability as a writer. Indeed, Benson's status as something of an anomaly and an outsider among her literary peers, writing against the grain of the modernist age of technical invention and literary trickery, was regarded by Hyde as a measure of Benson's success:

Why is the genius of Stella Benson not better appreciated among her contemporaries? I think it is because she was always so perfectly human that these machine-made young men and women suspected there was a catch in her. Breaking their necks, themselves, to achieve new tricks and gadgets, they looked about for Stella Benson's trick or gadget, and could not find it. If they had criticised her work adversely, they would have proved themselves idiots, so they took the simpler course and left her alone. The consequence is that Stella's books are in a world of their own. She is neither recognised 'highbrow' nor would the 'lowbrow' understand her. But she is very important: she had an insight into the fatal flaw of twentieth century construction – its dehumanising character – and she knew exactly how to reveal it. [4]

Hyde's devotion to Benson was such that she mourned the writer's premature death in 1933 at the age of 41. In a letter to Muriel Innes in 1936, Hyde wrote: 'I think you'd understand and love Stella Benson. She is dead and I

howled at the news of her death.'

The degree of Hyde's enthusiasm and deep emotional attachment to Benson's work has made it abundantly clear that more needs to be known about this forgotten writer, a writer in a world of her own, a writer so admired by Hyde that she desired to emulate her, even become her.

d.jpg) 2. Stella Benson

2. Stella BensonThere is some difficulty attending the creation of an accurate biographical profile of Stella Benson despite the fact that two biographies of her have been published. The first of these was written by R. Ellis Roberts, a freelance literary journalist who came to know Benson during the last five years of her life. Roberts'

Portrait of Stella Benson, 1939, is a highly sentimental memoir in which he asks the reader to 'look at this book as they would look at a painted portrait.' [6]

Drawing on his brief friendship with Benson along with information gleaned from the letters of her family and friends he created a biographical portrait that is at best a tribute to a woman and writer deeply admired by Roberts and at worst a saccharine and speculative record of a life, to the extent that he even supplies an account of Benson's dying thoughts, surely known only to herself. The following extract from Roberts' memoir illustrates the futility of relying on this biography for an objective or accurate account of Stella Benson's life and work:

Stella was a dancer. All her art, much of her life had the character of the dance. Is there not always sadness in the heart of the dancer? The gaiety of movement, the flight, the stillness and the following passionate movement, are controlled by the profound quiet at the centre: and there is melancholy, and a wondering doubt. The dancer in Stella, in Stella the woman more than Stella the artist, craved for immediate applause, for the deep murmur of an entranced audience, for the heedless impersonal adoration given to the world's charmers. She desired that success to cheer the melancholy in her heart. [7]

A second Benson biography, by Joy Grant, was published in 1987. Grant had access to Benson's forty diaries housed at the Cambridge University Library. The diaries, spanning thirty-one years of Benson's life, were embargoed for fifty years following her death and became available to researchers on 6 December 1983. In the preface to her book Grant described the enormous project of mining the wealth of Benson's diaries and selecting material for the resultant modestly sized 339 page biography:

Basing a biography upon a diary, I have learned, is like trying to sail a course in a cockleshell across a wild and stormy sea: there is altogether too much water, and it seems to be going in every direction at once. The best that the poor mariner-biographer can hope to do is hang on and pray that the tide will bring her in. [8]

Grant's biography offers a whistle-stop survey of Benson's life in which a raft of largely uncited diary entries and fragments from letters are connected by scant commentary. There is little system holding the biography together and the cockle shell boat of this mariner-biographer founders beneath the weight of the project she has undertaken; that of transforming and condensing Benson's highly detailed, diaristic account of her life into a coherent biography.

The inadequate referencing in the biography was a deliberate act as Grant explains in a brief section of notes and sources near the end of the book:

The main source for this book was the Diary of Stella Benson in the University of Cambridge Library. To provide separate references for each of the many quotations from this source would add an air of pedantry to its pages and vastly extend the notes to little advantage.Virtually all the diary quotations can in fact be dated, if not by day then by month and year, from the context. Where quotation is made from letters interleaved with the diary, however, a reference is supplied, and the location given as the University of Cambridge. [9]

This lack of pedantry on Grant's part has the unfortunate consequence of rendering the biography all but valueless as a scholarly research tool. [10]

Excavating the bones of biographical fact from the pages of the two skeletal biographies we learn that Stella Benson was born on 6 January 1892 at Lutwyche Hall, an Elizabethan Mansion in South Shropshire, England. She was the third of four children born to Ralph Benson, a member of the Shropshire landed gentry, and Caroline Essex Cholmondeley, sister of novelist Mary Cholmondeley. Stella’s early years were marred by ill health including a series of bronchial ailments and pleurisy. Her illness resulted in permanent deafness in her right ear by 1907.

By the time Stella was six, the family was living in London and moving frequently. She was educated at home under the direction of her mother, her maternal aunts, and governesses, and for a short period in Germany and Switzerland where she spent 17 months convalescing following a severe bout of pleurisy in her early teens. When Stella was fourteen, her parents publicly separated although for some years they had lived apart. Ralph Benson maintained sporadic contact with Stella and her two brothers George and Stephen (her older sister Catherine died in 1899 aged nine). Alcoholism and declining mental health took its toll on Stella's father and he died of a brain haemorrhage in 1911.

An enthusiastic reader, Stella had a powerful imagination and kept an almost daily diary from the age of ten until only a few months before her death. Interested in social issues from an early age, Stella was influenced by her mother and aunts who supported women’s suffrage. During the First World War Stella participated in the united war effort by working as a gardener on the land and by helping poor women in the East End of London earn a living. These jobs inspired her first three novels, beginning with

I Pose in 1915.

Shortly before the war ended, Benson wanted desperately to see more of the world. America was her first stop. With letters of introduction from feminist and literary contacts, including the poet Amy Lowell, Benson found congenial friends in a bohemian and artistic community in the San Francisco-Berkeley area. Here she came to know the minor poet Witter Bynner and the photographer Ansel Adams. Many of her Bay area acquaintances were to become life-long friends. Her experiences in California provided her with material for

The Poor Man (1922).

From California Benson made her first trip to China, where in 1920 she met James O’Gorman Anderson, an Anglo-Irish officer in the Chinese Customs Service (CCS). They married in 1921. Benson was thrust into the role of Colonial wife, a role she resisted throughout her marriage. An avid and perceptive reader, Anderson took considerable interest in his wife’s writing, but largely put his own profession first. A skilled linguist, he was an invaluable member of the CCS and committed to his profession. Marriage was disappointing to Benson. She found physical relations difficult and acknowledged her reticence. Although both wanted children, they did not succeed in having a family. Life in the remote Treaty Ports was lonely for Benson. An agnostic without children, she had little in common with the only other Western women nearby, wives of missionaries who were usually mothers of large families, without much interest in or time for literature.

This lack of close friends abroad and her increasing deafness, may be why Benson found comfort in her writing, diaries and correspondence, as well as with her pet dogs. Benson had a keen interest in psychology and used her diary to explore her inner emotions. The diaries reveal how very ill she was much of the time and the tremendous physical effort she gave to her writing. The chaotic conditions of civil wars in China made sending manuscripts and correcting proofs especially complicated.

Benson did enjoy the friendship of many fellow writers and intellectuals at home in Britain, including Winifred Holtby, Naomi Mitchison, Rebecca West, and Vita Sackville West. She admired women like Eileen Power and Virginia Woolf, but felt intellectually inferior to them. Power and Benson met in 1920 in India when Power was travelling on the Kahn Fellowship and Benson was visiting barrister and social reformer Cornelia Sorabjee. Both Power and Benson interviewed Gandhi. The women’s friendship lasted for the rest of Benson’s life.

Benson not only wrote fiction but also frequent journalistic articles for publications in the English-speaking world. These articles helped her achieve financial independence and often reflected her social concerns. Feminism, embraced by her mother and aunts, and their friends like Sorabjee, remained important to Benson. She spoke out against the abuse of women in traditional cultures, specifically prostitution and the sale of young Chinese girls, and joined forces with a group of Hong Kong Christian English women to effect legal changes regarding prostitution. Known as a witty writer who was not afraid to express unpopular views, she was often criticised by fellow expatriates in Asia. The issues of colonials, nationals, and colonialism were never far from Benson’s thoughts about her experience in China, Hong Kong, and the Treaty Ports. Her unfinished novel,

Mundos, addresses these issues. She was writing this novel at the time of her sudden death from pneumonia in Hongay Indo-China in 1933. Stella Benson was buried in the small French cemetery on the Île de Charbon, a little island near Hongay.

Stella Benson's corpus includes seven novels (published between 1915 and 1931), an additional unfinished novel (published posthumously in 1935), two limited-edition collections of short stories (published in 1931 and 1932), a complete collection of short stories (published in 1936), one slim volume of twenty poems (published early in Benson's career, in 1918), an expanded edition of poems selected by the author (published posthumously in 1935), a privately printed edition of the verse drama 'Kwan-Yin', two limited editions of individual short stories, 'The Awakening' and 'The Man Who Missed The Bus', two volumes of travel sketches (illustrated by Benson), and a biography of Russian-born Count Nicolas de Toulouse Lautrec de Savine.

3. Robin Hyde

3. Robin HydeA timeline of Robin Hyde's reading of Stella Benson's work gathered from letters, reviews and articles confirms that Hyde read at least six of Benson's novels, the collected poems and short stories and the first volume of travel sketches,

The Little World, 1932.

Robin Hyde first encountered the work of Stella Benson in her teenage years at Wellington Girls College (1919-1922) and her admiration for Benson endured for the remainder of Hyde's brief adult life. In a letter to poet Eileen Duggan, Hyde recalled that she left college ‘fathoms deep in love with’ a handful of authors, among whom was Benson. [11]

Wellington Girls College do not currently have any of Stella Benson's books in their library and they have no record of their collection during Hyde's time at the school. It is therefore a speculative but nonetheless interesting exercise to consider which of Benson's books Iris Wilkinson, the young Robin Hyde, might first have read. By 1922 Stella Benson had published four novels:

I Pose, 1915;

This is the End, 1917;

Living Alone, 1919;

The Poor Man, 1922; and a collection of twenty poems, called

Twenty, 1918 (most of which had appeared within the pages of her first two novels). Hyde did not read Benson's first novel

I Pose until 1928 [12]. The College library may well have had a copy of Benson's two early fantasy novels

This is the End and

Living Alone, featuring witches, dragons, and imaginary friends set against the unlikely backdrop of wartime London.

Such stories would certainly have appealed to Iris Wilkinson, the young 'schoolgirl poetess', writer of verse about goblins, fairytales and Arthurian legend who played the role of a wicked witch in the school's French Club production based on the Perrault fairytale 'La Belle au Bois Dormant' [13]. The disjunctive narrative of Benson's novel

The Poor Man, however, expressing a deeply cynical view of modern American culture, is less likely to have appeared on the Wellington Girls College library shelves. Hyde did in fact read

The Poor Man, referring to it briefly in her 1937 article 'Women Have No Star - Questions, Not Answers,' although it is not known in which year she read the novel.

While there is no mention of

This is the End or

Living Alone in Hyde's letters or reviews, the startling thematic and stylistic similarities beween

This is the End and Hyde's own fantasy novel

Wednesday's Children, 1937, (discussed in more detail below), make a compelling case that Hyde had most certainly read this book. It seems extremely probable that she also read

Living Alone.

In a letter to John Schroder, 23 March 1928, Hyde refers to three Stella Benson novels:

Goodbye Stranger, 1926;

I Pose, 1915; and

Pipers and a Dancer, 1924:

I'm so glad you liked Stella Benson. Because, later, I lent that book, Goodbye Stranger, to my mother: and she returned it with the comment, ‘Of course, the only excuse for the man is that he must have had a fall in childhood and been insane for some years.’ So that was that! But I loved the book and the fairies. Have read Pipers to [sic] a Dancer (why didn’t Ipsie jump over the moon while she had the chance?) and this week-end I’m going to extract I Pose from its lair in the library and indulge in more fairy-isms. [14]

Writing to Schroder three weeks later Hyde included her response to

I Pose, which is not a book of 'fairy-isms' but a story about the escapades of an unnamed militant suffragette who thwarts the love of an unnamed gardener by blowing herself up for the cause:

And did I tell you that I read Stella Benson's I Pose and could with pleasure have danced on her for hurting her gardener when she blew the little suffragette to pieces? I agree with you that she is sometimes cruel. She makes real people and then deliberately hurts them. [15]

Hyde and Schroder's shared reading and mutual admiration for Stella Benson's work developed over time from an informal conversational response into a more contextual and critical commentary on Hyde's part [16]. In 1932 Hyde discussed her reading of Schroder's copy of

Tobit Transplanted. She likens Benson to English fantasist Ronald Fraser and in doing so offers her first comparative response to Benson's writing:

I read your Tobit Transplanted. Wasn't the dog lovely - and can't one feel the breezes blow in Stella Benson's books? I don't remember whether you've ever told me if you liked Ronald Frazer [sic], who wrote Landscape With Figures, The Flying Draper, and Phantom Flowers [sic]. If by any lucky chance you don't know his books back to front, read them and I shall be happy in knowing that I've introduced you to someone you will like. He has some sort of likeness to Stella Benson - he is fourth dimensional too - but his people aren't her marvellous human folk. He really doesn't care a damn for humanity. He gives them eyes in the back of their heads and long flame-coloured plaits and then makes them ride on peach-coloured dragons across the China Sea. [17]

In a letter to Schroder written in 1935 from her voluntary residence at the Grey Lodge, the women's home at Auckland Mental Hospital, Hyde refers to Benson's volume of travel sketches

The Little World and her last unfinished novel

Mundos:

You read Stella Benson's The Little World, and her last and nearly loveliest, Mundos? John, I'd rather be Stella Benson than anyone else in the world. For she not only understood creatures, but she had music and a kindly laughter. There is no writer else does things like Tobit Transplanted, the dog in it, nor like her reflections on Excellencies in Mundos. If anyone has an excuse to be a ghost and run about spiritualist meetings babbling, it is Sam Wylie, in this book she half-finished. [18]

In December 1936 Hyde published a review of Benson's posthumous collection of short stories. Hyde's son and co-biographer Derek Challis observes perceptively that the review also served as an obituary for a much admired writer:

Stella Benson, of all modern writers, typified that with the most courage, the most humour, and the most skill. She was an artist who gives the impression of never having spent a moment worrying how to be an artist; her gift of writing was almost fully fledged when she started out (,) though her last two novels, ‘Tobit Transplanted’ and ‘Mundos’ were probably the most spirited of her work (…)

(…) She was almost always laughing, not with a J.M. Barrie Great-Chief-Smile-In-The-Rain whimsicality, not with any elaborate attempt at irony, but because, like the rest of her kind, she was rather a funny little creature and knew it. [19]

A further review of Benson's short stories appeared in

The Observer a month later, in January 1937. It is in this review that Hyde ranked Benson as one of the four great women writers of the twentieth century:

(…) Macmillan's paid her the rare compliment of publishing last year, after her early death, her half-finished novel, 'Mundos.' Now the first volume of collected short stories has appeared – not, I hope, the last one. This volume has all the brilliant and yet human talent of the woman who ranks as one of the twentieth century's four great women writers – the others being Mary Webb, Virginia Woolf, and, a long way after, Willa Cather.

Like the poetess Dorothy Wellesley, Stella Benson is modern without ever straining after modernism: there are no loud, fat, clanging machines in her stories, nor do the wheels creak, but through the mouths of commercial travellers, American 'Willies' like the typical one in 'An Out-Islander Comes Home,' (sic) down-trodden little figures like the spinster nurse in 'Hope Against Hope,' Stella Benson gives a panorama of the twentieth century which shows, on the small scale the short story can best handle, all the twentieth century's clash of machinery and individual hopes trodden into the dust or scattering like the mice who scattered before the giant wheels in 'The Man Who Missed the Bus,' hope dying lonely and with some nobility in the last tale, 'Story Coldly Told.' (…) [20]

Hyde referred to Benson's poetry in her 1937 article 'Women Have No Star - Questions Not Answers,' in which she reflects on the existence or non-existence of great women writers:

Stella Benson's poems, collected and published after her death, came into my hands the other day. She isn't the pure, that is, the abstracted, poet that Ruth Pitter is; but where among other writers of the twentieth century is the equal of her unstriving humanity? Her verses stick in the mind, with the haunting quality of old ballads; but there's a clearer, finer point to them than the sea rollings, and ship-swingings of such poets as, for instance, Masefield. And suddenly she laughs, or as suddenly, lets the mercy of Kwan-Yin speak from golden lips, or 'sows the dawn with birds.' [21]

4. Comparisons

4. ComparisonsThe process of formulating a timeline of Hyde's reading of Benson's work and assembling in chronological sequence her formal and informal responses highlights the fact that Hyde was more than simply a fan or admirer of Benson. She probed far beneath the surface of Benson's writing looking for the essence of her craft. It is my contention that by reading Benson, we learn a great deal about Hyde's own development as a writer.

My own (long-term) project is to unearth certain of these forgotten works of Stella Benson and to consider them in light of Hyde's commentary. Most importantly, here, I wish to put Hyde's own production alongside that of Benson and explore the idea that Hyde's practice as a writer was indebted to Benson. Ultimately I intend to reveal Benson as a secondary presence, a liminal author, existing at the threshold of Robin Hyde's writing.

The eclecticism of Hyde and Benson's writing practice is the first point of commonality between the two writers and provides an ideal starting point for a comparative analysis of their work. Their published work included poetry, fiction, short stories, journalism, travel articles, and biography.

Benson and Hyde shared a habit of interleaving poetry and prose. A number of Benson's early novels contain her own untitled poems as chapter breaks. Hyde noted this device in a letter to Muriel Innes, 8 February 1936:

And did you ever dig in one or two of Stella Benson's novels and find her scraps of poetry? [22]

Hyde used her own poetry in this way, as well as quotations from others, in her novels

Wednesday's Children, 1937,

The Godwits Fly, 1938, and in the unpublished novel 'The Unbelievers', 1935. In addition Michele Leggott has commented on Hyde's interleaving of poetry and prose in her 1934 autobiographical fragment (later published as

A Home in this World, 1984), and in the draft typescript of her collection of articles,

Journalese, 1934. Leggott suggests that these productions 'show clearly how the prose writer emerged from the poet and began testing the difference' [23].

I would suggest, however, that Hyde's adoption of this practice was influenced by her reading of Benson's work. Any comparative analysis of Benson and Hyde's fiction should include a discussion of their approach to the genre of fantasy, with particular emphasis on Benson's novel

This is the End, 1917 and Hyde's novel

Wednesday's Children, 1937. The two books are psychological fantasies set against a real life backdrop; in Benson's novel, London during World War I, and in Hyde's, Auckland in the 1930s. Hyde, it now seems clear, modelled

Wednesday's Children on Benson's earlier book, expanding on Benson's central theme of the imaginary life versus real life.

The popularity of the fantasy genre waned in the 1930s, a fact highlighted by setting the commercial and critical success of Benson's two wartime fantasy novels beside the failure of Hyde's own fantasy novel, published some twenty years later. The waning public interest in fantasy might also be considered in light of Hyde's inability to find a publisher for her collection of fantasy stories 'Unicorn Pasture' and her second fantasy novel 'The Unbelievers'.

There are a number of other examples of thematic and stylistic confluence in the work of Benson and Hyde which would warrant further investigation. In the novel

Tobit Transplanted Benson transplanted the Book of Tobit from the Old Testament Apocrypha into a modern context. This process recalls Robin Hyde's prophetic poem

The Book of Nadath.

The setting for Benson's unfinished novel

Mundos is the invented small island of Mundos, a British Crown Colony somewhere in the Atlantic governed by an ineffectual leader. The novel is a tragi-comedy of separateness that focuses on the complex relationships between a diverse cast of characters. An interesting comparison might be made between

Mundos and Hyde's unpublished novel 'The Unbelievers,' a fantasy story set on two fictional islands Aleua and Aüe, which Hyde described as 'comedy and fantasy with a magic island and communists and psychiatrists and idealised portraits of all my fair and false friends…' [24]

Hyde's effusive response to Stella Benson's short stories clearly motivated her own efforts in this genre. She published a number of stories in magazines and newspapers, as well as writing many more for the projected collection 'Unicorn Pasture.' It would be interesting to ask whether Hyde's stories succeed, like Benson's, in deploying the small scale of the genre to evoke a panoramic view of the twentieth century.

Benson and Hyde's creative approach to biography also provides a lively comparison. In the book

Pull Devil - Pull Baker, 1933, Benson produced a memoir of a colourful old gentleman whom she encountered in a hospital in Hong Kong. A penniless itinerant in failing health, Count Nicolas de Toulouse Lautrec de Savine sold his stories for ten dollars apiece to anyone who was willing to pay. Presenting himself as something of a Don Juan he told of how he once eloped with a Spanish royal princess, courted a French prima ballerina, along with a great many more romantic escapades, as well as an account of his youthful adventures as an officer in the Russian cavalry and his later ascent to the position of Tsar of Bulgaria for a single day.

Benson's book is constructed as a battle of wits between the analogical devil / editor and the baker / subject with alternating chapters representing their divergent points of view:

With regard to the title of our book I do not know…the origin of the phrase Pull Devil, Pull Baker … But my ignorance gives me the phrase to play with, and so I am free to identify the Count with a maker of airy blossom-white moral confectionery, and myself with a minor devil of sour eye and sweet tooth - and the two of us pulling in opposite directions. Pull Devil, Pull Baker expresses, at any rate, the lack of team-work only too apparent in the making of this book. [25]

The story of an equally spirited individual is recounted in Robin Hyde's

Check to Your King, 1936, the historical novel/ biography of Frenchman Baron Charles de Thierry and his attempt to establish a kingdom on the Hokianga in 1835. Hyde used a novelist's licence to compose the book, imaginatively expanding the framework of the story sourced from the de Thierry papers held at Auckland Public Library. Hyde regarded her role in the telling of de Thierry's story as an interpreter rather than historian as she made clear in a letter to writer Eric Ramsden:

I am not a historian, and don't want to be one. It is the individual and the mind moving behind queer, unreasonable actions which seem to me to produce a good deal of the fun of this old world; and I think that any writer has the right to interpret this as best he can, always allowing that the public has an equal right to criticism, or, worse, of failing to buy our confounded books. [26]

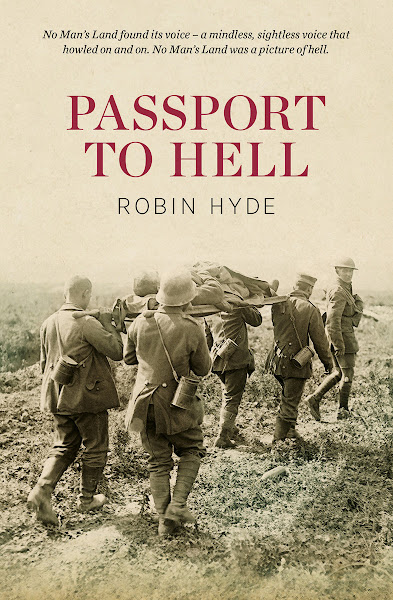

Hyde found a living subject for her book

Passport to Hell, 1936, a biography of James Douglas Stark, a bomber in the Fifth Regiment of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces during World War One. Stark's early life as an unhappy child who aggressively defied authority led to a life of notoriety as a young soldier whose antagonistic attitude toward his commanding officers was tempered by his quite extraordinary feats of bravery on the battlefields.

Nor The Years Condemn, something of a fictionalised biography and the sequel to

Passport to Hell was published two years later. The story followed Stark's difficulties readjusting to life in New Zealand after the horrific experience of war and his attempts to eke out a living in the depressed economic climate of post-war New Zealand. Hyde's prefatory note to

Nor The Years Condemn asserts that the book is largely a work of fiction, the object for its creation being the representation of the 'boom and bust' period in New Zealand and its effect on the lives of ordinary New Zealanders.

Finally, there is Hyde's book

Dragon Rampant, 1939, an account of her experiences travelling through China in 1938. This should be read alongside Benson's two collections of travel articles

The Little World, 1925 and

Worlds Within Worlds, 1928. For the most part Benson's travel sketches recount her observations of local life and customs in China. The articles, originally published in periodicals including the

New York Bookman, the

Nation and

Athenaeuem, and the

South China Morning Post, provided the writer with a steady income although this was a source of consternation for her. Benson berated herself for writing in a tone of excessive sprightliness in order to guarantee the appeal of her articles to readers of the popular press. [27]

Comparing the China caught in the midst of Japanese invasion, witnessed by Hyde in 1938, with the China experienced by Benson only a few years earlier, puts into stark relief the similarities and differences between the two writers. The poems from Hyde's China notebook include the enormously powerful 'East Side,' which describes the remains of a temple in a bombed and deserted village housing a statue of Kwan-Yin, the Chinese Goddess of Mercy. Hyde's poem can be compared to Benson's verse drama

Kwan-Yin, a work deeply admired by Hyde.

A question remains as to why Hyde went to China, thus deviating from her original plan to travel to London via Australia, Manila, Hong Kong, Kobe, Vladivostok, Moscow, Warsaw, and Berlin. In the first of a series of articles titled 'I Travel Alone' Hyde wrote:

Theoretically I have been in London for some months, but it is now April 13, and I still find myself in Hankow. Really the intervening stages are hard to explain, except that as soon as I stood on the not at all Chinese soil of Hong Kong, the conviction that I wasn't going any place but China came over me, and took root. [28]

Was her decision to travel to China in any way impelled by her desire to follow in the footsteps of Stella Benson?

c.jpg) 5. Pulling up the Chooks

5. Pulling up the ChooksThe ideal analogy for my project can be found in a diary entry written by Stella Benson on St George's Day, 23 April 1917. As a landwork volunteer during the war Benson was planting potatoes and pulling weeds (which she called chooks) at a farm owned by an ill-tempered old farmer called Mash. She described the nature of this back-breaking work:

Some chooks are so long that I think they must go right through to New Zealand, especially as they are green at the nether tip. I suppose they are New Zealandish chooks at the other end. The whole field seems to quake as they come up, and then they often snap when one has got no more than two or three hundred yards out, which makes me think there may be somebody weeding simultaneously in New Zealand, occasionally hitting on the same chook as me, and pulling the other way. [29]

The image of Benson tugging at a green tipped weed in an English field that is being simultaneously tugged by someone in New Zealand perfectly encapsulates the notion of Hyde's desire to emulate Benson.

Unbeknownst to Benson, a New Zealand writer fourteen years her junior was engaging her in a tug-of-words. A more expansive analogy of working the land might have it that Hyde cultivated the terrain of Benson's writing, excavating meaning, digging at the ideological layers of Benson's work, and harvesting her unique expressive and stylistic ability. Like tilling a field Hyde turned over all of these things in her mind and then into that same field she planted and cultivated her own creative self. The result, as the following comparison will hopefully elucidate, is that a number of aspects of Hyde's writing can be viewed as an outcrop of Benson's not strictly in an imitative sense but in the sense that Benson's work is a clearly discernible vein running through Hyde's creative production.

Part Two: Wednesday's Children and This is the End

* Plot summary:Stella Benson. This is the End. London: Macmillan, 1917.

Set during the war, the main character Jay has run away from home and taken a job as a bus conductress; only her beloved brother knows where she is and he's sworn not to tell. She sends false letters home telling her family not about her real life in East London but about her imaginary home, a 'House by the Sea', where she lives with her secret male friend and a host of happy children. Her family, (made up of a similar cast of characters to those in Wednesday’s Children) set out to look for her. They are accompanied by a Mr Russell, a middle-aged married man who, unawares, has already met Jay in her role as a bus conductress and been attracted to her and her to him. In his past Mr. Russell was himself a denizen of the world of fantasy (just like Bellister) and through his agency they locate the spot where Jay's House by the Sea should be. It has been demolished. When Jay learns about her family's discovery her fantasy world starts to crumble. She settles for married life with a pleasant but dull man and the House by the Sea becomes only a ghostly memory for her.

Although there is no mention in Hyde's letters of her reading Stella Benson’s second book, the many similarities between the story and the characters in

Wednesday's Children (1937) and

This is the End (1917) suggest strongly that Hyde had read the novel. Perhaps it was one that she read at Wellington Girls College between 1919-22 which had, according to Derek Challis an 'extensive. well-endowed school library' (

Book of Iris, 27) [30].

Textual clues include the names of minor characters in

Wednesday’s Children: Mavis Trelawney / Constable Kew.

In

This is the End the central character Jay has a brother named Kew and her secret friend residing in her imaginary world has a dog called Trelawney. There is a reference to a Mavis Trelawney in

Wednesday’s Children: Ronald Gilfillan is remembering Wednesday, the sixth bridesmaid at his wedding:

He saw her brown paws fly up into the air, as Brenda, turning at the bend of the stairs, tossed to the laughing girls her bouquet of white heather, white lilac. He heard the high, honey coloured giggle of Mavis Trelawney, who had caught the bouquet. His heart felt warm and sad for Wednesday. (29)

Then there is Jay's brother Kew in

This is the End. Constable Kew in

Wednesday’s Children searches for the runaway Attica who has kidnapped a member of the Vienna Boys choir (150-151). Both Kew's are men in uniform - Policeman and soldier. But constable Kew is in plain clothes.

Both novels begin with a veiled call for the suspension of belief in the machinations of the world, address to the reader a veiled request that the reader needs to suspend ideas about reality, of what is known and seen and accurate recordings that this is not the stuff that will be found in the pages of these two novels. The narrator of Benson's novel, in particular, directs the reader away from the illusion of facts and into a second, much vaster illusory space of the imagination:

This is the end, for the moment, of all my thinking, this is my unfinal conclusion. There is no reason in tangible things, and no system in the ordinary ways of the world. Hands were made to grope, and feet to stumble, and the only things you may count on are the unaccountable things. System is a fairy and a dream, you never find system where or when you expect it. There are no reasons except reasons you and I don't know.

I should not be really surprised if the policeman across the way grew wings, or if the deep sea rose and washed out the chaos of the land. I should not raise my eyebrows if the daily press became the Little Sunbeam of the Home, or if Cabinet Ministers struck for a decrease of wages. I feel no security in facts, precedent seems no protection to me. The wisdom you can find in an Encyclopedia, or in Selfridge's Information Bureau, seems to me just a transitory adaptation to quicksand circumstances.

But if the things which I know in spite of my education were false, if the eyes of the sea forgot their secret, or if the accent of the steep woods became vulgar, if the fairy adventures that happen in my heart fell flat, if the good friends my eyes have never seen failed me,--then indeed should I know emptiness, and an astonishment that would kill.

Hyde has a more convoluted way of saying much the same thing. In the opening chapter of

Wednesday's Children we are introduced to a small woman in a fur coat entering a newspaper office in Auckland at 'precisely 7.30 on the night of June 22nd. (13) This activity is followed by the narrator's analysis of different kinds of people:

There are still some Flat-Worldians, or, as Swift called them, Big-Endians, who have not yet been trained by crossword puzzles, the increasing strangeness of politics, or the mystery of the League of Nations (which is so rapidly replacing that of the Holy Trinity in modern life), to use their imagination. To these, such a statement as the above will convey nothing. It will be heard absently, with one or with half one ear, received into a brain like cotton-wool, and forever forgotten. You must have met such people. In the midst of a rubber of bridge, they quite suddenly het up, twiddle the black knobby nose on the expressionless face of the radio, and produce out of nowhere the most appalling shrieks, cut clean amidships. You cannot for the life of you tell whether it is one of those Russian art murders, where everyone stands about saying 'Tovarish' as the pig bleeds his last, or merely Gracie Fields soothing the savage breasts of the Lancastrians.They return to their chairs, with neat, tucked-in little smiles of gratification on their lips. They have, however, not the faintest idea of the appalling thing they have done, or why they did it. Their functioning is purely automatic, and involves neither purpose nor recollection. I should explain that from this class is drawn the larger number of ghosts. At the end of their lives, they fail to realse that they have died, and go on doing and saying just what they have always said and done. This accounts for the surprisingly inane character of the séance.

At a karma-stage slightly higher are those who, hearing mention of actions in a strange city, a strange country, will lay down their newspapers, saying vaguely: 'Auckland? Auckland?' Is New Zealand in Australia, they will wonder, or is it the other way about? But they will go no further with the matter.

By elimination, we come thus to the ideal type of listener… the man who knows a bit, and can believe or imagine much more

* Introductions:This is how Benson introduces us to Jay - The outer Jay:

I want to introduce you to Jay, a 'bus-conductor and an idealist. She is not the heroine, but the most constantly apparent woman in this book. I cannot introduce you to a heroine because I have never met one.

She was a person who took nothing in the world for granted, but as she had only a slight connection with the world, that is not saying very much. Her answer to everything was "Why?" The fundamental facts that you and I accept from our youth upwards, like Be Good and You Will Be Happy, or Change Your Boots When You Come In Out Of The Wet, or Respect Your Elders, or Love Your Neighbour, or Never Cross Your Legs Above The Knee, did not impress Jay.

I never knew her as a baby, but I am sure she must have been born a propounder of questions, and a smiler at the answers she received. I daresay she used to ask questions--without result--long before she could talk, but I am quite sure she was not embittered by the lack of result. Nothing ever embittered Jay, not even her own pessimism. There is a finality about bitterness, and Jay was never final. Her last word was always on a questioning note. Her mind was always open, waiting for more. "Oh no," she would tell her pillow at night, "there must be a better answer than that ..."

Perhaps it is hardly necessary to add that she had quarrelled with her Family, and run away from home. Her Family knew neither what she was doing nor where she was doing it. Families are incurably conceited, and this one supposed that, having broken away from it, Jay was going to the bad. On the contrary, she was a 'bus-conductor, but I only tell you this in confidence. I repeat the Family did not know it, and does not know it yet.

The Family sometimes said that Jay was an idealist, but it did not really think so. The Family sometimes said that she was rather mad, but it did not know how mad she was, or it would have sent her away to live in a doctor's establishment at Margate. It never realised that it had only come in contact with about one-fifth of its young relation, and that the other four-fifths were shut away from it. Shut away in a shining bubble world with only room in it for one--for One, and a shining bubble Story.

And what of the inner Jay?

I do not know how universal an experience a Secret Story and a Secret Friend may be. Perhaps this wonder is a commonplace to you, only you are more reticent about it than Jay or I. But to me, even after twenty years' intimacy with what I can only describe as a supplementary life that I cannot describe, it still seems so very wonderful that I cannot believe I share it with every man and woman in the street.

The great advantage of a Secret Story over other stories is that you cannot put it into print. So I can only show you the initial letter, and you may if you choose look upon it as an imaginary hieroglyphic. Or you may not.

Just this, that a bubble world can contain a round and russet horizon of high woods which you can attain, and from the horizon a long view of an unending sea. You can run down across the dappled fields, you can run down into the cove and stroke the sea and hear the intimate minor singing of it. And when you feel as strong as the morning, you can shout and run against the wind, against the flying sand that never blows above your knees. And when you feel as tired as the night, you can climb slowly up the cliff path and go into the House, the House you know much better than any house your ordinary eyes have seen, and there you will find your Secret Friends. The best part about Secret Friends is that they will never weary you by knowing you. You share their House, your passing hand helps to polish the base of that wooden figure that ends the banisters, you know the childish delight of that wide short chimney in the big turret room, a chimney so wide and so short that you can stand inside the great crooked fireplace and whisper to the birds that look down from the edge of the chimney only a yard or two above you. You know how comfy those big beds are, you sit at the long clothless table in the brown dining-room. With all these things you are intimate, and yet you pass through the place as a ghost, your bubble enchantment encloses you, your Secret Friends have no knowledge of you, their story runs without you. Your unnecessary identity is tactfully ignored, and you know the heaven of being dispassionate and detached among things you love.

All these things can a bubble world contain. You have to get inside things to find out how limitless they are. And I think if you don't believe it all, it is none the less true for that, because in that case you are the sort of person who believes a thing less the truer it is.

If Jay's Family did not know she was a 'bus-conductor, and did not know she was a story-possessor, what did it know about her? It knew she disliked the smell of bananas, and that she had not taken advantage of an expensive education, and that she was Stock Size (Small Ladies'), and that she was christened Jane Elizabeth, and that she took after her father to an excessive extent, and that she was rather too apt to swallow this Socialist nonsense. As Families go, it was fairly well informed about her.

How are we introduced to Wednesday in Hyde's novel? On the one hand there's the outer Wednesday, a small woman in a fur coat stepping out of the rain and pushing her way through the doors of the

Comet offices:

Wednesday did not look like a sea-lion, as she wrote out her advertisement, for which one of the clerks handed her a form, saying: 'Tuppence-word-over-there-please.' But she did look like some kind of friendly wet animal, and not only because of her coat. Her eyes, deep-set and brown, sometimes looked small as hazel-nuts. On the other hand, she had the trick of letting two black flowers in their centres suddenly open out, wide and lustrous. She had a little brown face, running to smile and wrinkle, with delicate plucked brows which tried to get together and commune at the top of her nose. Wrinkles lay softly under her skin, from which you might deduce that she was every day of thirty-seven. Her fawn-coloured kid gloves were damp, and when she peeled them off you could imagine her hands busy shelling acorns or removing the blood-red peel from some tropical fruit. They were little, deft, wrinkled, with pointed fingers thin as claws. (15)

On the other hand there's the inner Wednesday:

The clerk who received Wednesday's advertisement along with the correct sum had sealed eyes and 'he saw no more than a lady who wore démodée sealskins. But a drunkard outside the Comet office saw a very different Wednesday descending the stairs.

He was drunken, white-haired and unshaven, drunken enough to remember his youth. He came forward and caught at her sleeve, saying: ''Scuse me, lady, 'scuse me.' Wednesday did not much like drunken men, not because she disapproved of them as a fact, but because there seemed so little she could do with them. She drew her arm away, smiling uncertainly. But the drunken man remembered yet more of his youth. With wonderful clearness he saw the great rosy and crystal wings unfold behind her head. He saw the lissome slightness of Wednesday's body, and how it could dance like a mad shepherdess, who is nevertheless at heart so respectable that she might easily induce Pan to wear pants. He saw Wednesday girt about with symbols, corn-sheaves, stout doves and olive branches.

[…]

Behind her voleishness, the other and taller presence shone out. It could carry wheat-sheaves and poppies without looking incongruous. It was a sort of domesticated angel, yet not without a sense of humour (16)

Thus, in the opening pages of both novels, we learn that the two central female characters are doubles and that they are leading double lives. They are not what they appear at first sight to the casual observer. For example (

This is the End, 40):

From the moment when Mr. Russell left her 'bus, Jay became stupefied by an invasion of the Secret World.

She gave the tickets and change with accuracy, she kept count of the stream of climbers on to the top of the 'bus, she stilled the angry whirlpool of people on the pavement for whom there was no room, she dislodged passengers at the corners of their own streets--even that gentleman (almost always to be found in an obscure corner of an east-going 'bus) who had sunk into a sudden and pathetic sleep just when his pennyworth of ride was coming to an end,--she received an unexpected inspector with the smile that comes of knowing every passenger to be properly ticketed; she even laughed at his joke. She weeded out the Whitechapel Jewesses at the Bank, and introduced them to the Mile End 'buses. She handed out to them their sombre and insolent-looking babies, and when one mother thanked her profusely in Yiddish, she replied, "Bitte, bitte...." Yet all the while the wind blew to her old remembrances of the low chimneys and the bending roofs of the House by the Sea, and the smell of the high curving fields, and the shouting of the sea. And all the while her hands must grope for the handle of the heavy door, and her eyes must fill with blindness because of the wonderful promise of distant cliffs with the sun on them, and because the sea was so shining. And all the while her ears must strain to hear a voice within the house....

It is a very great honour to be given two lives to live.

Both Russell and Bellister are outsiders drawn into family affairs, and -- in particular -- the case of the missing female relation.

Russell encounters Jay in her other occupation as a London bus conductor.

Bellister encounters Wednesday in her other occupation as Madame Mystera.

Both men fall in love with the alternate persona - Wednesday and her island and Jay and her house by the sea.

Wednesday and Jay are both loved by 'older and wiser' men: Hugo Bellister and Herbert Russell. These men have links to the secret world but have forgotten the connection and the way there. Wednesday and Jay awaken their dormant fantasy selves.

Both are struggling to remember their youth. The drunk outside the post office in Wednesday’s Children who is drunk enough to remember his youth and sees Wednesday's other presence prefigures the character of Bellister and his forgotten second self.

* Mr Russell:

(This is the End, 28) Russell's remembrance of Jay's house by the sea is triggered by Anonyma's description of the place they seek in order to recover their runaway relation Jay as described to them in a letter from her:

"It is a quest with a certain amount of romance in it," agreed Anonyma. "We are seeking a House By The Sea. We know very little about it except that it exists. We know that its windows look west, and that the sun sets over the sea. We know that it stands ungardened on the cliff and has a great view. We know that it is seven hundred years old, and full of inspiration ..."

"We know," continued Kew, "that you can--and often do--drop a fishing-line out of the window into the sea when you are tired of playing the goldfish in the water-butt. We know that the owner of the house is a rotten shot, and that the stone balls from the balustrade are not at this moment where they ought to be. We know that aeroplanes as well as seagulls nest in those cliffs...."

"We know--" began Mr. Russell, but this was too much for Mrs. Gustus. After all, the lady was her admirer.

"What's all this?" said Mrs. Gustus. "What do you people know about it?"

"I just thought I would talk a little now," said Kew. "I get quickly tired of hearing other people giving information without help from me."

"At any rate, Russ," continued Mrs. Gustus, "you can't know anything whatever about the matter. You have hardly listened when I read Jay's letters."

"I told you that I remembered," said Mr. Russell. "I don't know how. I remember sitting on a high cliff and seeing three black birds swim in a row, and dive in a row, and in a row come up again after I had counted hundreds."

"Nonsense," said Mrs. Gustus, trying not to appear cross before the visitor, "you're thinking of something else. You can see such a sight as that at the Zoo any day."

Russell imagines he knows Jay's secret place, just as Bellister feels an immediate affinity with Wednesday's island (

This is the End, 38):

"What's the use of looking for this girl?" she asked, after a round of duty. "Why not leave her on her happy shore? Do you know, sir, I sympathise enormously with that girl."

"I don't expect you would if you knew her," said Mr. Russell. "She must be quite different from you, by what I hear from her relations. I think she must be an aggressive, suffragetty sort of girl. Girls nowadays seem to find running away from home a sufficient profession."

"You say that because you are so dreadfully much Older and Wiser," said Jay. "Why are you looking for her, then?"

"I'm not," said Mr. Russell. "She is just a trespasser. I'm looking for the place because I know I know it."

"I hope you'll never find it," said Jay crossly. She announced Ludgate Circus in a startling voice, and ended the conversation.

A second letter from Jay stirs Mr Russell's memory further (

This is the End, 51):

On the breakfast table, when they returned, they found a letter from Jay, evidently written for private circulation in the Family.

Dear Kew--I have just come in from a walk almost as exciting as it was beautiful. We walked through our village, which clings to both sides of a crack-like harbour that might just contain a carefully navigated walnut-shell. The village is grey and white, all its walls are whitewashed, all its roofs are slate with cushions of stone-crop clinging to them. Sea-thistles grow outside its doors, seagulls are its only birds. The slope on which it stands is so steep that the main road is on a level with the roofs on one side, and if you were absentminded, you might walk on to a roof and fall down a chimney before you became aware that you had strayed from the street. But we were not absent-minded. We sang Loud Songs all the way. We ran across the grass after the shadows of the round clouds that bowled across the sky. In single file we followed the dog Trelawney after the seagulls. Everything was so clear that we could see the little rare island that keeps itself to itself on our horizon. I don't know its name; they say it bears a town and a post-office and a parson, but I don't think this is true. I think that island is an intermittent dream of ours. When you get beyond the village, the cliff leaves off indulging in coves and harbours and such frivolities, and decides to look upon itself seriously as a giant wall against a giant sea. Only it occasionally defeats its own object, because it stands up so straight that the sea finds it easier to knock down. On a point of cliff there was a Lorelei seagull standing, with its eye on Trelawney. It had pale eyes, and a red drop on its beak. And Trelawney, being a man-dog, did what the seagull meant him to do. He ran for it, he ran too far, and fell over the edge. Well, this is not a tragic incident, only an exciting one. Trelawney fell on to a ledge about ten foot below the top of the cliff, and sat there in perfect safety, shrieking for help. My Friend said: "This is a case of 'Bite my teeth and Go.'" It is a saying in this family, dating from the Spartan childhood of my Friend, that everything is possible to one who bites his teeth and goes. The less you like it, the harder you bite your teeth, and it certainly helps. My Friend said: "If we never meet again, remember to catch and hang that seagull for wilful murder. It would look rather nice stuffed in the hall." The cliff overhangs rather just there, and when he got over the edge, not being a fly or used to walking upside down, he missed his footing. We heard a yelp from Trelawney. But the seagull's conscience is still free of murder, my Friend only fell on to Trelawney's ledge. So it was all right, and we ate our hard-Book of Irisled eggs on the scene of the incident.

"I remember--" said Mr. Russell.

Neither Jay nor Wednesday will allow Russell or Bellister entry into their secret world. Bellister arrives at the shore of Wednesday's island but she will not take him further. Jay tried to drag Russell there in her imagination but he got left outside (

This is the End, 63):

She thought a good deal about Mr. Russell. I am sure that he would have laughed painfully could he have seen the picture of himself that remained with the 'bus-conductor. The picture made him thinner, and his eyes more intelligent, and the line of his mouth happier, but it did not make him look younger, because Jay liked him to be Older and Wiser. He never came into the Secret World; several times she tried to drag him thither, but always at the critical moment he got left outside. Yet I cannot say that in her Secret World she missed him; the point of the bubble enchantment is that there is nothing lacking in it.

* Love:What is the nature of Wednesday and Jay's love for Bellister & Russell? (

This is the End, 63):

Jay filled her day with unsatisfactory thinking. She found to her surprise that one may love life and yet also think lovingly of death. To live is most interesting in an uneasy way, but to die is to forget at once all these trivial turbulences, to forget equally the people you have loved and the people you have hated, to forget everything you ever knew, to be alone, and to be no longer disturbed by unceasing voices.

At this time I think Jay felt more hatred of everybody than love of any one person. But then, of course, she had vowed to Chloris after the affair with young William Morgan that she would never fall in love again. She said, "I have been through love. It is not a sea, as people say. It is only a river, and I have waded through it."

"Yet there is certainly something very remarkable about that man," she thought. "I don't believe I like him much, I don't want to know him better, though I should like him to know me. I believe he is my real next of kin. I believe he has a Secret World too."

When Russell declares his love ... (

This is the End, 73):

"Ladylike!" snorted Jay. "What's the use of ladyliquity even for five minutes? So Kew sent you as an antidote? I suppose he didn't know you were one of my fares?"

"A fare," said Mr. Russell sententiously, "may, I suppose, be a wonderful revelation, because you only see your fare's eyes for a second, and the things you may see have no limit, and you never know the silly little truth about him. Yet even so, there is more than a ticket and a look between you and me, and you know it."

"Possibly there is a Secret World between you and me," said Jay. "But that's a pretty big thing to divide us."

"Supposing it doesn't divide us?" said Mr. Russell, looking fiercely at the road in front of him. "Supposing it showed me how much I love you?"

"How disappointing!" said Jay in the worst of possible taste. (She was like that to-day.) "You're ceasing to be an Older and Wiser, and trying to become an ordinary Nearah and Dearah."

("Oh, curse," she thought in brackets. "I shall kick myself to-night.")

"That's a horrid thing to say," said Mr. Russell. "But still I do love you."

"It sounds very Victorian and nice," said Jay, wondering if he could still see her through her veil of bad temper. "But, you know, in spite of Secret Worlds, and secret souls, and centuries of secret knowledge, we still have to keep up this 1916 farce, and leave something of ourselves in sensible London. How do I know you're not married?"

Mr. Russell thought for a very long time indeed, and then said, "I am."

Jay was not very well brought up. She did not stop the car and step out with dignity into respectable Hackney. She was just silent for a long time.

"As you were," she said to herself, when she found herself able to think again. "This is a bad day, but it will be over in something less than a hundred years."

"You drive well," she said presently, looking with relief from Mr. Russell's face to his hands. Christina the motor car and two 'buses were just then indulging in a figure like the opening steps of the Grand Chain. "You drive as though driving were poetry and every mile a verse."

"After all," she told herself, "the man loves me, and I must at least take an intelligent interest in him."

* Peter and Paul:Compare Mr Russell on St Paul (

This is the End, 38) ...

Mr. Russell was too early for his business, and he went into St. Paul's and sat on a seat far back.

St. Paul was an anti-saint, I think, who very badly needed to get married and be answered back now and then. I believe it is possible that he was unworthy of that great house called by his name. The gospel of a very splendid detachment speaks within its walls, its windows turn inward, its music sings to itself. Tossed City sinners go in and out, and pass, and penetrate, but still the music dreams, and still the dim gold blinks above their heads. A muffled God walks the aisles, and you, in the bristling wilderness of chairs, can clutch at His skirts and never see His eyes. Nothing comes forward from that altar to meet you. It is as if He walked talking to Himself, and as if even His speech were lost in those devouring spaces.

... to Mr Bellister on St Peter: (

Wednesday's Children, 169):

'Saint Peter,' said Mr Bellister, 'who lets people in at the gates. I should think society might be astonished if they knew just whom he does let in, and whom he bars. Over a period of twenty centuries, one should become a shrewd judge of bores. ...'

* Getting to the truth:Compare Bellister/ Wednesday with Russell/Jay:

They both confide the truth. Jay shares stories about her house by the sea and all the little details. Russell tells about his secret friend too. They think they have happiness and then go home to the news that Kew has died. The dream dies with him.

Wednesday tells the truth in a letter and drowns herself.

* The final scene:Bellister and Russell are both at the location of the house by the sea. One is a shack, one is a drowned house.

Reality has blown the bubble world away.

Bellister's creation of shell tombstones and seeing an image of Attica rush by.

Russell and Bellister imagine footprints in the sand.

* Plot similarities:They are both runaways.

They both pose in other jobs. Wednesday as fortune teller/ Jay as bus conductor.

Both Jay and Wednesday have an affinity with the poor. Wednesday donates all her winnings to the Anstruther Children's home for orphans. Jay had been working in the Brown Borough with poor families since War broke out. (

This is the End, 7)

J & W both have similar families and have been taken in by relations and don't fit in. Wednesday has a harder time though - made to feel unwanted.

Uncle Elihu is akin to Kew - complicit in the great deception and delighting in the game being played.

Wednesday's Children has a lot more supplementary characters and a lot more intertextual clues - Michael Arlen's

Green Hat, fairytales, poetry, Fitzgerald's

Rubaiyat ...

They both fabricate other lives and struggle with the truth:

"You haven't told me about the sea yet," said Kew.

"Because I don't think you'd believe me. We were always liars, weren't we? That's because we're romantic, or if it's not romance, the symptoms of the disease are very like. Why can't we get rid of it all as Anonyma does? She has no gift except the gift of being able to get rid of superfluous romance. She takes that great ease impersonally, her pose is, 'It's a gift from Heaven, and an infernal bore.' But I never get nearer to joy than I do in this Secret World of mine, and with my Secret Friend."

"But what is it? What is he like?"

"I should be guilty of the murder of a secret if I told you. He isn't particularly romantic. I have seen him in a poor light; I have watched him in a most undignified temper; I have known him when he wanted a shave. I don't exist in this World of mine. I am just a column of thin air, watching with my soul."

"Then you're really telling lies to Anonyma when you write about it all? I'm not reproaching you of course, I only want to get my mind clear."

"I suppose they're lies," assented Jay ruefully, "though it seems sacrilege to say so, for I know these things better than I know myself. But Truth--or Untruth, what's the use of words like that when miracles are in question?" (This is the End, 12)

Compare these ideas about the truth to Wednesday's suicide letter to Bellister:

'It's all William Shakespeare's fault,' wrote Wednesday, 'Shakespeare, at all events, began it […] It was Shakespeare who in after years kept saying to me, "To thine own self be true."

'And then when it all went so badly - living where I wasn't wanted, and looking such an insignificant plain kitchen pot, and dropping stitches in bedsocks no same person would have worn, anyway, I began to wonder, 'Which self? Which self? True to which self? You see Mr Bellister, most surface selves are such lies. […]

'I was always in bad trouble, Mr Bellister, with the truth. Not so much knowing what it is, as knowing which it is. My truths were amoebae, they had second selves, split personalities, double faces. If I write to you now the really true truth, you'll say, 'Poor daft Wednesday,' and your faith in me will vanish like mist. If I write you the other, the seeming truth, it's so inadequate. Oh, well.' (197-98)

* Home:The perfect homes for both Wednesday and Jay are imaginary constructs - The House by the Sea for Jay and the House by the Sea for Wednesday: 'Entente Cordiale'.

Jay's secret world is populated by an unnamed secret friend, dream children, an old woman and a dog named Trelawney. Wednesday's by five children, ocasional visitors from those who have fallen off the edge of the world, occasional lovers, a Maori nanny Maritana.

This is Jay's House by the Sea (

This is the End, 40):

She found presently that the great weight of copper money was gone from her shoulder, and that it was evening, and that Chloris was coming down Mabel Place to meet her. Chloris was wagging her whole person from the shoulder-blades backwards; she never found adequate the tail that had originally been provided for that purpose. Jay stumbled up the step of Eighteen Mabel Place, and found at last the path she wanted.

The path was one that had never been touched by a professional pathmaker. Feet, not hands, had made it. The rocks impatiently thrust it aside every little way, and here and there were steps up and down for no reason except that the rock would have it so. The path chose its way so that you might see the sea from every inch of it. The thundering headlands sprang from Jay's left hand, and she could see the cliffs written over with strange lines, and the shadow that they cast upon deep water. It was the colour of a great passion, and against that colour pink foxgloves bowed dramatically upon the fringe of space. The white gulls were in the valleys of the sea. I wish colour could be built by words. I wish I could speak colour to myself in the dark. I can never fill my eyes full enough of the colour of the sea, nor my ears of the crying of the seagulls. I am most greedy of these things, and take no thought for the morrow, so that if my morrow dawns darkly I have nothing stored away to comfort me.

The path joins the more civilised road almost at the door of the House by the Sea. You tumble over a great round rock that still bears the marks of the sea's fingers, and you are at the door.

The house was full of sunlight. Great panels of sunlight lay across the air. The fingers of the honeysuckle in the rough painted bowl by the window caught and held sunlight. In every room of the house you can always hear the eternal march of the sea up and down the shore. Nothing ever drowns that measured confusion. Sometimes the voices of friends thread in and out of it, sometimes the dogs bark, or a coming meal clinks in the stone passage, or you can catch the squealing of the children in their baths, sometimes your heart stops beating to listen to the speech of the ghosts that haunt the house, but no sound ever usurps the throne of the sea.

As for the occupants of Jay's House by the Sea (

This is the End, 41):

They were all on the stairs, the Secret Friend and the children. They all wore untidy clothes, and hard-Book of Irisled eggs bulged from their pockets. The Secret Friend has red hair, you might call its colour vulgar. But Jay likes it very much. He hardly ever sits still, you can never see him think, he has a way of answering you almost before you have finished speaking. His mind always seems to be exploring among words, and sometimes you can hear him telling himself splendid sentences without meaning. For this reason everything connected with him has a name, from his dog, which is called Trelawney, to the last cigarette he smokes at night, which is called Isobel. This trick Jay has imported into her own establishment: she has an umbrella called Macdonald, and a little occasional pleurisy pain under one rib, which she introduces to the Family as Julia.

The children in the house were just those very children that every woman hopes, or has hoped, to have for her own.

They were just starting for a walk, and the Secret Friend was finishing a story.

* Names:Wednesday Sabrina GilfillanWednesday - child of woe

Sabrina - latin meaning from the border land

Sabrina means "goddess of Severn River" or "legendary princess" in English. In Latin, Sabrina means "from the border". Another variant of this name is Breen, Breena, Brina, Zabrina, Zavrina.

Stella Benson's

Living Alone includes a chapter entitled 'Regrettable Wednesday'

Jay / Kew:'The great advantage of a Secret Story over other stories is that you cannot put it into print. So I can only show you the initial letter, and you may if you choose look upon it as an imaginary hieroglyphic. Or you may not. (

This is the End, 2).

Jane Elizabeth becomes Jay - the initial letter all her family knew of her.

* Poems:R. Ellis Roberts.

Portrait of Stella Benson. London: Macmillan, 1939, 46.

In these early books Stella interspersed the text with poems. An author who does this confesses, as a rule, that he doubts whether he has in the main body of his work told his dearest secret; or he is hoping for readers who will delight in the ambiguity that is so much characteristic of poetry than prose; or, in re-reading his work, he feels suddenly the need for the sharper, directer communication that is the poet's privilege…(Roberts 46)

Benson explains the impetus for writing poetry through the narrator in

This is the End (61):

I hope that the feeling of making poetry is not confined to the people who write it down. There is no luxury like it, and I hope we all share it. I think perhaps the same thrill that goes through Mr. Russell and me when the ghost of a completed thing begins to be seen, also delights the khaki coster who writes his first--and very likely last--love-letter from France; and the little old country mother who lies awake composing the In Memoriam of her son for a local paper; and the burglar "down 'Oxton" who takes off his cap as a child's funeral goes by. The feeling is: "This is a thing out of my heart that I am showing. This is my best confession, and nobody knew there was this within me." I am sure that that great glory of poetry in one's heart does not wait on achievement. If it did, what centuries would die unglorified. It is just perfection appearing, to your equal pride and shame, a perfection that never taunts you with your limitations.

In Benson's

Goodbye Stranger, 1926, each of the 14 chapters begins with a poem. Benson's verse drama 'Kwan Yin, Goddess of Mercy,' is placed at the beginning of her novel

The Poor Man, 1922.

The difference between Hyde and Benson is that Hyde also quotes from the poems of others in her work. Eg: Attica reading "Heart's Desire" from the

Rubaiyat (142-43):

'Before you go,' said Wednesday, who had drained several glasses of burgundy and was feeling mildly exhilarated, 'just one stanza, darling.'

'Hand then of the potter shake?' asked Attica.

'Never blows so red the rose,' suggested Dorset. Wednesday shook her head. 'Heart's desire,' she said. So Attica, in crimson velvet and with the tiniest fragment of attar-of-roses buried under her black cloud of hair, stood in the middle of the room, and said:

'Ah, love, could thou and I with Fate conspire

To grasp this sorry scheme of things entire

Would we not shatter it to bits – and then

Remould it nearer to the heart's desire.

Ah, Moon of my delight, that know'st no wane,

The moon in Heav'n is rising once again….'

The lovely young voice went on till the end of the poem. 'That's all right,' said Wednesday, the garnet in her wine-glass and the crimson-black of her daughter's toga mixed with the multitude of rose-petals smouldering and falling in the Rubaiyat, 'life couldn't be better…' (143)

Benson describes Jay as a busconducting Omar Khayyam (

This is the End, 68)

"There are only dreams," she thought very lucidly, "to keep our souls alive. We are lucky if we get good dreams. We'll never get anything better."

Through the glass between the patriotic posters that darkened the windows she could see the morbid colour of London air.

"Apart from dreams," thought this busconducting Omar Khayyám, "there is nothing but disappointment. We expected too much. We expected satisfaction. There is nothing in the world but second bests, but dreams are an excellent second best. Our last attitude must be 'How interesting, but how very far from what I wanted....'"

The speed of time, and the hurry of life suddenly rushed upon her again.

"I must hurry," she said. "Or I shan't have lived before I die. I must hurry."

* Critical responses to This is the End and Wednesday’s Children:Why was Benson's novel successful and Hyde's not?

At the time of its publication

This is the End sold well and received excellent reviews in

The Bookman,

The Times Literary Supplement and

Punch. Benson's biographer Joy Grant suggests that a reason for the favourable reviews might be because the 'vogue for Barrie made critics more indulgent of waywardness and whimsy than they would otherwise have been.' (Grant: 99)

Consider the popularity of the fantasy genre in fiction in the period preceding and during WW1. Fantasy and War; escapism? Joy Grant writes that at the time of writing

Living Alone, Stella Benson felt she had 'the key to a marvellous, if dangerously seductive, theatre of fantasy available only to the privileged few.' (Grant: 139)

Consider the significance of the setting of Benson's fantasy novel in wartime. The plot navigates between the real world and a fantasy world like Hyde's

Wednesday’s Children. Perhaps one reason for

Wednesday’s Children's lack of success was that it came 20 years too late when the appeal of the fantasy genre and Stella Benson's fantasy style of writing was on the wane.

Bibliography:

Bibliography: Books by Stella Benson

Books about Stella Benson

Footnotes:1. Iris Wilkinson, letter to John Schroder, [Friday night] 1935, Schroder 83, Lisa Docherty '"Do I speak well?": a selection of letters by Robin Hyde 1927-1939' PhD Thes., U of Auckland, 2000.

2. Allan Irvine, Notebook 1936, Derek Challis and Gloria Rawlinson, The Book of Iris: A Life of Robin Hyde, Auckland: Auckland UP, 2002, 392.

3. Robin Hyde, 'Rare and Understanding; Collected Short Stories by Stella Benson,' The New Zealand Observer. 7 Jan.1937, Rpt. in Disputed Ground: Robin Hyde, Journalist, ed. Gillian Boddy and Jacqueline Matthews, (Wellington: Victoria UP, 1991) 226.

4. Robin Hyde, 'Rare and Understanding,' Boddy and Matthews, 226.

5. Iris Wilkinson, letter to Muriel Innes, 8 Feb. 1936, Challis and Rawlinson, 314.

6. R. Ellis Roberts, Portrait of Stella Benson (London: Macmillan, 1939) vii.

7. Roberts, 357.

8. Joy Grant, Stella Benson: A Biography (London: Macmillan 1987) xviii.

9. Grant, 323.

10. Marlene Baldwin Davis, Lecturer in English at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia is currently researching Benson's diaries with a view to publishing a book. The book will be modelled on historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's 1990 Pulitzer Prize winning book A Midwife's Tale: The life of Martha Ballard Based on her Diary, 1785-1812. Ulrich's meticulously detailed book in which diary entries, historical context and insightful commentary are brilliantly interwoven would act as an ideal template for the analysis of Stella Benson's diaries.

In April 2005 Adam Matthews Publications, England, specialists in the publication of historical research collections, released the complete set of Stella Benson's diaries on microfilm.

Irish novelist Annabel Davis-Goff, great niece of Stella Benson's husband James O'Gorman Anderson, is currently writing a book about Benson, Anderson and his brother Sainthill Anderson who died in the First World War.

11. Robin Hyde, letter to Eileen Duggan, 12 April 1935, Lisa Docherty, ed., 'Stumblers in the hinterlands: Robin Hyde's letters to Eileen Duggan'.

12. Iris Wilkinson, letter to John Schroder, 23 March 1928, Challis and Rawlinson, 106.

13. Challis and Rawlinson, 32.