A new translation of the Thousand and One Nights can be quite a hard sell. You'll note that I've listed some 27 of them at the foot of this post - and that's just a selection ...

They range from the first - and still most influential - Antoine Galland's 12-volume French translation (1704-17), to a more recent 4-volume Spanish translation by Salvador Peña Martín (2016).

Among them there are a dozen or so English versions, at least three of them - Payne, Burton, and Lyons - claiming to be 'complete' (whatever, precisely, that can be taken to mean):

- Anonymous (from Antoine Galland) [1706-21] (French / English)

- George Lamb (from Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall) [1826] (French / English)

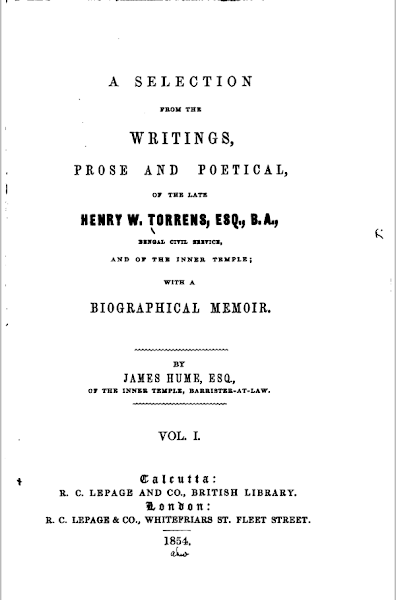

- Henry Torrens [1838] (English)

- Edward W. Lane [1839-40] (English)

- John Payne [1882-89] (English)

- Richard F. Burton [1885-88] (English)

- Andrew Lang (mostly retold from Galland) [1898] (English)

- Laurence Housman (mostly retold from Galland) [1907-14] (English)

- E. Powys Mathers (from Dr. J. C. Mardrus) [1923] (French / English)

- A. J. Arberry [1953] (English)

- N. J. Dawood [1954-57] (English)

- Husain Haddawy [1990-95] (English)

- Malcolm & Ursula Lyons [2008] (English)

The Annotated Arabian Nights, together with her earlier single-volume Aladdin, constitute all that we've seen so far of French-Syrian poet and translator Yasmine Seale's 1001 Nights. It's possible that there may be more to come, however. According to her Wikipedia entry Seale "is the first woman to translate the entirety of The Arabian Nights from French and Arabic into English."

The "entirety of The Arabian Nights" cannot be referring solely to Seale's and her collaborator Paulo Lemos Horta's Annotated Arabian Nights. While that book certainly presents a very extensive selection from the immense body of materials which constitute the Nights, it can certainly not be called "complete."

Richard F. Burton (1885-88) filled 16 closely-printed volumes with his own attempt to provide a complete Arabian Nights. A good deal of that consisted of annotation and commentary, but the same cannot be said of John Payne (1882-89), whose translation eventually occupied 13 volumes of text, covering much the same territory.

The most recent "complete" English version of the Egyptian recension of the Nights (by far the most extensive of the various textual traditions), by Malcolm C. & Ursula Lyons (2008), occupies three volumes and 2,700-odd pages. But even that has been (lightly) edited for repetitions and redundancies.

Perhaps the most complete (and most universally praised) modern translation, Jamel Eddine Bencheikh and André Miquel's 3-volume French version for the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (2005-07) clocks in at 3,504 pages.

So what precisely is Seale's contribution to the Arabian Nights tradition? Here's Wikipedia again, in their page dedicated to the One Thousand and One Nights:

A new English language translation was published in December 2021, the first solely by a female author, Yasmine Seale, which removes earlier sexist and racist references. The new translation includes all the tales from Hanna Diyab and additionally includes stories previously omitted featuring female protagonists, such as tales about Parizade, Pari Banu, and the horror story Sidi Numan.The reference to Hannā Diyāb is to a young Syrian traveller who visited Europe in the early eighteenth century, and - among all the other adventures detailed in his recently translated travel book - seems to have been the informant "Hanna from Aleppo" who told (or wrote out for?) Antoine Galland the so-called "orphan tales" which occupy the bulk of the last four volumes - roughly a third - of his translation.

To call Hannā Diyāb the co-author of the collection, as Paulo Lemos Horta does in his 2017 book Marvellous Thieves, is therefore no real exaggeration. Galland's diary for the period 1708-15 record details of 14 stories told him by the sbove-mentioned "Hanna from Aleppo". Roughly ten of these, albeit in greatly expanded form, made it into the final text of his Mille et une nuits (1704-17):

As you can see, they include such classic tales as "Aladdin" and "Ali Baba". Galland made no reference to this indebtedness in any of his published writings. However, since he died while his translation was still in progress (the final two volumes appeared posthumously), this may have been more inadvertent than deliberate.

- Histoire d'Aladdin ou la Lampe merveilleuse [The Story of Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp] (told in 1709: May 5) [included in Galland, Vol. 9]

- Les aventures de Calife Haroun Alraschid [The Night Adventures of Caliph Haroun-Al-Raschid] (May 10) [Vol. 10]

- Histoire de l'Aveugle Baba-Alidalla [The Story of the Blind Baba-Alidalla]

- Histoire de Sidi Nouman [History of Sidi Nouman]

- Histoire de Cogia Hassan Alhababbal [The Story of Cogia Hassan Alhababbal] (May 29) [Vol. 10]

- Histoire d'Ali-Baba et de quarante voleurs exterminés par une esclave [Tale of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves] (May 27) [Vol. 11]

- Histoire d'Ali Cogia, Marchand de Bagdad [The Story of Ali Cogia, Merchant of Baghdad] (May 29) [Vol. 11]

- Histoire du Cheval enchanté [The Ebony Horse] (May 13) [Vol. 11]

- Histoire du prince Ahmed et de la fee Pari-Banou [History of Prince Ahmed and the Pari-Banou] (May 22) [Vol. 12]

- Histoire des deux Soeurs jalouses de leur cadette [The Story of the two sisters jealous of their younger sister] (May 25) [Vol. 12]

But going back to Yasmine Seale's original translation of Aladdin. In his Guardian review of the book (2/11/18), Richard Lea quotes her as admitting that these recent discoveries of the full extent of Galland's indebtedness to Hannā Diyāb have had little effect on her version, since “the only text we have is Galland’s, and that is what I have to work with”:

But knowing the story of the tale’s construction makes Aladdin “a document of exchange, of translation on several levels, a product of both the Arabic and French literary traditions.”Seale continues, “I’m less interested in what ‘a Frenchman’ or ‘a Syrian’ might have invented than in the particular voices of these two men”:

Both came from learned, cosmopolitan cities. They were complex products of their knowledge and experience – who isn’t? Each was familiar with and fascinated by the other’s culture and language.As for the Nights themselves, she sees them as "part of the bloodstream of world literature. They’re furniture, like the great myths. Because of their endless, slippery nature (a sea of stories without an author) they have flowed freely across borders of language and genre.”

In an earlier interview with Wendy Smith for Publisher's Weekly (10/10/18), Seale revealed something of her own background, and the reason why she sees herself as such an ideal translator for such "slippery", cross-cultural works:

My mother is Syrian, but my father was a mix: his parents were Russian and Tunisian, he had grown up in Britain, and both my parents wrote in English. I grew up speaking and hearing three languages: French, English, and Arabic. For a long time I felt that I was just going to be French; my studies focused on French literature, and that was going to be my identity. Then I thought, ‘No, I must learn Arabic and understand it properly — that’s part of my heritage.’ That’s why this work has been so pleasurable; I feel I can bring all that to the table and I don’t have to choose. Galland’s description of Topkapi Palace — which I can see from my window — finds its way into the descriptions of the mythical palaces in Aladdin, but so do Diyab’s experiences at the palace of Versailles. Aladdin is neither just an Orientalist fantasy, nor is it just the vision of a Syrian person in France; it’s both at the same time, and I find it moving that it can be both.

This sense of the Nights as a work so contaminated by diverse cultural influences that the very notion of "fidelity to the original", normally so crucial in translation, becomes literally meaningless, underlies Seale's work on both Aladdin and the Annotated Arabian Nights. As she herself puts it:

Fidelity to what? When you have a story that exists in 80 different versions, you have to make choices. To translate the Nights means continuing to shape the stories and acknowledging that you are bringing your own sensibility to them rather than pretending it doesn’t exist.Finally, it seems, the Nights may have found a translator who not only understands but actually embodies their paradoxical nature:

I was trying to bring out the freshness, vivacity, and wit I saw in the original French; Galland was an incredibly witty and playful person. I didn’t want to do what a lot of other translators of the Nights have done, which is to translate it into deliberately archaic language. The 19th-century translators all did this, Richard Burton most famously; his translations, even by Victorian standards, are incredibly florid and elaborate. It was a way of creating this sense of distance from the world these texts came from — a sense that the East was unfathomable, strange, and alien. I wanted to bring out the modernity that is already in the text.

I have to acknowledge the truth in this. Much though I adore Burton's Nights, it is almost necessary to learn a new language, Burtonian, to understand them. Perhaps that's why they've had such an influence on writers who were not native speakers of English: Jorge Luis Borges, most famously, but also Hugo von Hoffmansthal in Austria and Junichiro Tanizaki in Japan.

Her comments on the actual process of translation are fascinating, too:

Translating the 14th-century Arabic texts is “a completely different experience,” Seale comments. “Galland’s style is fairly close to what we would recognize as English prose, but in the Arabic there is no punctuation; clauses are separated by the word wa, which means and, or the word fa, which can mean so, or then, or however, or because. As a translator, you have to intervene to shape the narrative and create a readable English paragraph. To want ‘authenticity’ in The Arabian Nights is a bit of a misnomer: these are stories that have continually shifted, that are constantly changing, that are made of their accretions and layers.”

It's perhaps a bit cheeky - not to mention somewhat predictable - to suggest an analogy here with the legendary Scheherazade herself, subject - as well as putative author - of the Arabian Nights in much the same sense as we postulate the authors of other "inspired" writings. But then, Seale does almost invite the comparison:

"In the framing story that begins the Nights, this king kills his unfaithful wife and decides to take a new woman every night and kill her in the morning,” she explains. “Scheherazade intervenes and says, ‘I will save my sisters from this fate.’ What we know about her from the story is that she has collected books, she has a library, she has studied and memorized tales from previous times and the history of bygone ages. She is in this sense a translator and reinterpreter of these stories. Thinking about Scheherazade helped me think about the whole text as a series of conduits — stories being channeled through a series of vessels, Scheherazade being one. Every single person who has written them down, every translator, everyone who’s added to this ocean of stories, is a kind of boatman ferrying the stories along. It makes sense to me, rather than thinking about this binary of original and translation, to break down that boundary.As for her own relationship to the text:

Translating Aladdin, Yasmine Seale says, “made me feel like there was a plan in my life all along and everything had been leading to this moment.” Speaking from a sun-drenched room in her home in Istanbul, she explains, “It was written down in the 18th century by a Frenchman, Antoine Galland, based on the story he was told by a young Syrian traveler named Hanna Diyab, so it is both a product of France and also of the Arab world. I grew up in France and studied French literature, with a particular interest in the 18th century, and then went to university and studied Arab literature. So it’s a text that combines my two great interests."In other words, she too has "collected books", she too "has a library", and "has studied and memorized tales from previous times and the history of bygone ages."

So if we are being invited here to imagine Yasmine Seale as a Scheherazade for our own times, what better USP [= Unique Selling Point] could there be for a new translation of this most evergreen, baffling, and slippery of works, the Arabian Nights?

Seriously, how can you hesitate to add this beautifully illustrated and annotated new translation to your own bookshelf? I, for one, am thoroughly sold.

-

Texts & Translations:

- Texts [c.800-1986] [Arabic]

- Antoine Galland [1704-1717] (French)

- Dom Dennis Chavis & M. Cazotte [1788-89] (French)

- Maximilian Habicht [1824-25] (German)

- Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall et al. [1826] (French / German / English)

- Gustav Weil [1837-41] (German)

- Henry Torrens [1838] (English)

- Edward W. Lane [1839-40] (English)

- John Payne [1882-89] (English)

- Richard F. Burton [1885-88] (English)

- Max Henning [1895-97] (German)

- Andrew Lang [1898] (English)

- Dr. J. C. Mardrus [1899-1904] (French)

- Cary von Karwath [1906-14] (German)

- Laurence Housman [1907-14] (English)

- Enno Littmann [1921-28] (German)

- M. A. Salye [1929-36] (Russian)

- Francesco Gabrieli [1948] (Italian)

- A. J. Arberry [1953] (English)

- Rafael Cansinos-Asséns [1954-55] (Spanish)

- N. J. Dawood [1954-57] (English)

- René R. Khawam [1965-67 & 1985-88] (French)

- Felix Tauer [1928-34] (Czech & German)

- Husain Haddawy [1990-95] (English)

- Jamel Eddine Bencheikh & André Miquel [1991-2001 & 2005-7] (French)

- Malcolm & Ursula Lyons [2008] (English)

- Salvador Peña Martín [2016] (Spanish)

- Yasmine Seale [2019-2021] (English)

- Miscellaneous

- Alph Laylé Wa Laylé. 4 vols. Beirut: Al-Maktaba Al-Thakafiyat, A.H. 1401 [= 1981].

- Arabic Key Readers. A Thousand and One Nights: Graduated Readings for English Speaking Students – Book 1: Story of the Book, Nights 1 through 9. Retold by Michel Nicola. Troy, Michigan: International Book Centre, 1986.

- Zotenberg, Hermann. Histoire d’Alâ al-Din ou La Lampe Merveilleuse: Texte Arabe publié avec une notice sur quelques manuscrits des Mille et une nuits. Paris; Imprimerie Nationale, 1888.

- Galland, Antoine, trans. Les Mille et Une Nuits: Contes arabes traduits par Galland. 12 vols. 1704-17. Ed. Gaston Picard. 2 vols. 1960. Paris: Garnier, 1975.

- Galland, Antoine, trans. Les Mille et Une Nuits: Contes arabes. 12 vols. 1704-17. Ed. Jean Gaulmier. 3 vols. 1965. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1990, 1985, 1991.

- Arabian Nights Entertainments: Consisting of One Thousand and One Stories, Told by the Sultaness of the Indies, to divert the Sultan from the Execution of a bloody Vow he had made to marry a Lady every day, and have her cut off next Morning, to avenge himself for the Disloyalty of his first Sultaness, &c. Containing a better Account of the Customs, Manners, and Religion of the Eastern Nations, viz. Tartars, Persians, and Indians, than is to be met with in any Author hitherto published. Translated into French from the Arabian Mss. by M. Galland of the Royal Academy, and now done into English from the last Paris Edition. London: Andrew Bell, 1706-17. 16th ed. 4 vols. London & Edinburgh: C. Elliot, 1781.

- The Arabian Nights. Illustrated with Engravings from Designs by R. Westall, R. A. 4 vols. London: Printed for C and J. Rivington et al., 1825.

- Forster, the Rev. Edward, trans. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. 1812. Rev. G. Moir Bussey. Illustrated by 24 Engravings from Designs by R. Smirke, Esq. R. A. London: Joseph Thomas / T. Tegg; and Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1840.

- Galland, A. Las Mil y Una Noches: Cuentos orientales. Trans. Pedro Pedraza y Páez. Biblioteca Hispania. Barcelona: Editorial Ramón Sopena, 1934.

- Mack, Robert L., ed. Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. The World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Chavis, Dom, and M. Cazotte, trans. La Suite des Mille et une Nuits, Contes Arabes. Cabinet des Fées 38-41. 4 vols. Geneva: Barde & Manget, 1788-89.

- Habicht, Max., Fr. H. von der Hagen, and Carl Schall, trans. Tausend und Eine Nacht, Arabische Erzählungen. 1824-25. Ed. Karl Martin Schiller. 12 vols. Leipzig: F. W. Hendel, 1926.

- Lamb, George, trans. New Arabian Nights' Entertainments, Selected from the Original Oriental Ms. by J. Von Hammer, and Now First Translated into English. 1826. 3 vols in 1. Milton Keynes, UK: Palala Press, 2015.

- Weil, Gustav, trans. Tausendundeine Nacht. 1837-41. Ed. Inge Dreecken. 3 vols. Wiesbaden: R. Löwit, n.d. [c. 1960s]

- Torrens, Henry, trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night: Translated from the Arabic of the Ægyptian M.S. as edited by Wm. Hay Macnaghten, Esqr. 1838. India: Pranava Books, n.d.

- Lane, Edward William, trans. The Thousand and One Nights, Commonly Called, in England, The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. A New Translation from the Arabic, with Copious Notes. 3 vols. London: Charles Knight, 1839-41.

- Lane, Edward William, trans. The Thousand and One Nights; Commonly Called The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Ed. Edward Stanley Poole. 3 vols. 1859. London: Chatto, 1912.

- Lane, Edward William, trans. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Ed. Stanley Lane-Poole. 4 vols. 1906. Bohn’s Popular Library. London: G. Bell, 1925.

- Lane, Edward William, trans. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments or The Thousand and One Nights: The Complete, Original Translation of Edward William Lane, with the Translator’s Complete, Original Notes and Commentaries on the Text. New York: Tudor Publishing Co., 1927.

- Lane, Edward William, trans. The Thousand and One Nights, or Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Wood Engravings from Original Designs by William Harvey. London: Chatto and Windus, 1930.

- Payne, John, trans. Oriental Tales: The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night [and other tales]. 1882-97. 15 vols. Herat edition (limited to 500 copies): No. 141. London: Printed for Subscribers Only, 1901.

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night; Now First Completely Done into English Prose and Verse, from the Original Arabic. 9 vols (London: Villon Society, 1882-84)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 2)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 3)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 4)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 5)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 6)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 7)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 8)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (vol. 9)

- Tales from the Arabic of the Breslau and Calcutta (1814-’18) Editions of the Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, Not Occurring in the Other Printed Texts of the Work; Now First Done into English. 3 vols. (London: Villon Society, 1884)

- Tales from the Arabic (vol. 2)

- Tales from the Arabic (vol. 3)

- Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp; Zein ul Asnam and the King of the Jinn: Two Stories Done into English from the Recently Discovered Arabic Text (London: Villon Society, 1889)

- The Persian letters, with introduction and notes, done into English from the original by Montesquieu (London, 1897)

- A Thousand and One Quarters of an Hour and Tartarian Tales, by Thomas Simon Gueulette (London, 1897)

- Payne, John, trans. The Portable Arabian Nights. 1882-1884. Ed. Joseph Campbell. 1952. New York: The Viking Press, 1963.

- Payne, John, trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night. 1882-1884. Publisher's Note by Steven Moore. 3 vols. Ann Arbor, MI: Borders Classics, 2007.

- Burton, Richard F, trans. A Plain and Literal Translation of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, Now Entituled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: With Introduction, Explanatory Notes on the Manners and Customs of Moslem Men and a Terminal Essay upon the History of the Nights. 10 vols. Benares [= Stoke-Newington]: Kamashastra Society, 1885. N.p. [= Boston]: The Burton Club, n.d.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Supplemental Nights to the Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night with Notes Anthropological and Explanatory. 6 vols. Benares [= Stoke-Newington]: Kamashastra Society, 1886-88. 7 vols. N.p. [= Boston]: The Burton Club, n.d.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments. 1885. 10 vols. U.S.A.: The Burton Club, n.d. [c.1940s].

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Supplemental Nights to the Book of the Thousand and One Nights with Notes Anthropological and Explanatory. 1886-88. 6 vols. U.S.A..: The Burton Club, n.d. [c. 1940s].

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments. 1885. Decorated with 1001 Illustrations by Valenti Angelo. 3 vols. New York: The Heritage Press, 1934.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments. 1885. Decorated with 1001 Illustrations by Valenti Angelo. 3 vols. 1934. The Heritage Press. New York: The George Macy Companies, Inc., 1962.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, or The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Selection of the Most Famous and Representative of these Tales. Ed. Bennett A Cerf. 1932. Introductory Essay by Ben Ray Redman. New York: Modern Library, 1959.

- Burton, Sir Richard, trans. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Notes by Henry Torrens, Edward Lane, John Payne. Illustrations by Arthur Szyk. 1955. The 100 Greatest Books Ever Written. Norwalk, Connecticut: The Easton Press, 1983.

- Burton, Richard F. Love, War and Fancy: The Customs and Manners of the East from Writings on The Arabian Nights. Ed. Kenneth Walker. 1884. London: Kimber Paperback Library, 1964.

- Chagall, Marc, illus. Arabian Nights: Four Tales from a Thousand and One Nights. Introduction by Norbert Nobis. Trans. Richard F. Burton. Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1988.

- Zipes, Jack, ed. Arabian Nights: The Marvels and Wonders of the Thousand and One Nights, Adapted from Richard F. Burton’s Unexpurgated Translation. Signet Classic. New York: Penguin, 1991.

- Zipes, Jack, ed. Arabian Nights, Volume II: More Marvels and Wonders of the Thousand and One Nights, Adapted from Sir Richard F. Burton’s Unexpurgated Translation. Signet Classic. New York: New American Library, 1999.

- Henning, Max, trans. Tausend und eine Nacht. 1895-97. Ed. Hans W. Fischer. Berlin & Darmstadt: Deutsche Buch-Gemeinschaft, 1957.

- Lang, Andrew, ed. Tales from the Arabian Nights. Illustrated by H. J. Ford. 1898. London: Wordsworth Classics, 1993.

- Lang, Andrew, trans. Tales from The Arabian Nights. 1898. Illustrated by Edmond Dulac. Afterword by Pete Hamill. The World’s Best Reading. Sydney & Auckland: Reader’s Digest, 1991.

- Mardrus, Dr. J. C., trans. Le Livre des Mille et une Nuits. 16 vols. Paris: Édition de la Revue blanche, 1899-1904. Ed. Marc Fumaroli. 2 vols. Paris: Laffont, 1989.

- Mathers, Edward Powys, trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night: Rendered from the Literal and Complete Version of Dr. J. C. Mardrus; and Collated with Other Sources. 1923. 8 vols. London: The Casanova Society, 1929.

- Mardrus, Dr J. C. The Queen of Sheba: Translated into French from his own Arabic Text. Trans. E. Powys Mathers. London: The Casanova Society, n.d. [1924].

- Mathers, E. Powys. Sung to Shahryar: Poems from the Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night. London: The Casanova Society, 1925.

- Mathers, E. Powys, trans. Arabian Love Tales: Being Romances Drawn from the Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, Rendered into English from the Literal French Translation of Dr. J. C. Mardrus. Illustrated by Lettice Sandford. London: The Folio Society, 1949.

- Mathers, E. Powys, trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night: Rendered into English from the Literal and Complete French Translation of Dr. J. C. Mardrus. 4 vols. 1949. 2nd ed. 1964. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972.

- The Arabian Nights: The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, Rendered into English from the Literal and Complete French Translation of Dr. J. C. Mardrus by Powys Mathers. Introduction by Marina Warner. 6 vols. London: The Folio Society, 2003.

- Vol. 1: with 8 colour illustrations by Kay Nielsen, 375 pp.

- Vol. 2: with 8 colour illustrations by Grahame Baker, 424 pp.

- Vol. 3: with 8 colour illustrations by Debra McFarlane, 424 pp.

- Vol. 4: with 8 colour illustrations by Roman Pisarev, 424 pp.

- Vol. 5: with 8 colour illustrations by Jane Ray, 431 pp.

- Vol. 6: with 8 colour illustrations by Neil Packer, 448 pp.

- Karwath, Cary Von, trans. 1001 Nacht: Vollständige Ausgabe in 18 Taschenbüchern mit einem Zusatzband: Nach dem arabischen Urtext angeordnet und übertragen von Cary von Karwath. 1906-14. 19 vols. München: Goldmann Verlag, 1987.

- Housman, Laurence. Stories from the Arabian Nights. Illustrated by Edmund Dulac. 1907. New York: Doran, n.d.

- Housman, Laurence. Sindbad the Sailor and Other Stories from the Arabian Nights. Illustrated by Edmund Dulac. 1907. Weathervane Books. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1978.

- Littmann, Enno, trans. Die Erzählungen aus den Tausendundein Nächten: Vollständige deutsche Ausgabe in zwölf Teilbänden zum ersten mal nach dem arabischen Urtext der Calcuttaer Ausgabe aus dem Jahre 1839 übertragen von Enno Littmann. 1921-28. 2nd ed. 1953. 6 vols in 12. Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1976.

- Littmann, Enno, trans. Geschichten der Liebe aus den 1001 Nächten: Aus dem arabischen Urtext übertragen von Enno Littmann. Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1973.

- Salye, M. A., trans. Тысяча и Одна Ночь. 1929-36. 6 vols. Санкт-Петербург: «Кристалл», 2000.

- Gabrieli, Francesco, ed. Le mille e una notte: Prima versione integrale dall’arabo. Trans. Francesco Gabrieli, Antonio Cesaro, Constantino Pansera, Umberto Rizzitano and Virginia Vacca. 1948. Gli struzzi 35. 4 vols. Torino: Einaudi, 1972.

- Faccioli, Emilio, ed. Le mille e una notte: Scelta di racconti. Dall’edizione integrale diretta da Francesco Gabrieli. Letture per la Scuola Media 56. Torino: Einaudi, 1980.

- Arberry, A. J., trans. Scheherazade: Tales from the Thousand and One Nights. London: Allen and Unwin, 1953.

- Arberry, A. J., trans. Scheherazade: Tales from the Thousand and One Nights. Illustrations by Asgeir Scott. 1953. A Mentor Book. New York: New American Library, 1955.

- Cansinos Asséns, Rafael, trans. Libro de las mil y una noches, por primera vez puestas en castellano del árabe original. Prologadas, anotadas y cotejadas con las principales versiones en otras lenguas y en la vernácula por Rafael Cansinos Asséns. 3 vols. 1954-55. Mexico: Aguilar, 1990.

- Dawood, N. J., trans. The Thousand and One Nights: The Hunchback, Sindbad, and Other Tales. Penguin 1001. 1954. Penguin Classics L64. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1955.

- Dawood, N. J., trans. Aladdin and Other Tales from The Thousand and One Nights. Penguin Classics L71. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1957.

- Dawood, N. J., trans. Tales from the Thousand and One Nights. 1954-57. 2nd ed. 1973. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

- Khawam, René R., trans. Les Mille et une nuits. Traduction Nouvelle et Complète faite sur les Manuscrits par René R. Khawam. 4 Vols. Paris: Editions Albin Michel, 1965-67.

- Khawam, René R., trans. Les Mille et une nuits. 4 vols. 1965-67. 2nd ed. 1986. Paris: Presses Pocket, 1989.

- Khawam, René R., trans. Les Aventures de Sindbad le Marin. Paris: Phébus, 1985.

- Khawam, René R., trans. Les Aventures de Sindbad le Terrien. Paris: Phébus, 1986.

- Khawam, René R., trans. Le Roman d’Aladin. Paris: Phébus, 1988.

- Tauer, Felix, trans. Tisíc a Jedna Noc. 1928-34. 5 vols. 1973. Praha: Ikar, 2001.

- Tauer, Felix, trans. Erotische Geschichten aus den tausendundein Nächten: Aus dem arabischen Urtext der Wortley Montague-Handschrift übertragen und herausgegeben von Felix Tauer. 1966. Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1983.

- Tauer, Felix, trans. Neue Erzählungen aus den Tausendundein Nächten: Die in anderen Versionen von »1001 Nacht« nicht enthaltenen Geschichten der Wortley-Montague-Handschrift der Oxforder Bodleian Library; Aus dem arabischen Urtext vollständig übertragen und erläutert von Felix Tauer. 2 vols. 1982. Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1989.

- Haddawy, Husain, trans. The Arabian Nights: Based on the Text of the Fourteenth-Century Syrian Manuscript edited by Muhsin Mahdi. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1990.

- Haddawy, Husain, trans. The Arabian Nights II: Sindbad and Other Popular Stories. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1995.

- Heller-Roazen, Daniel, ed. The Arabian Nights. The Husain Haddaway Translation Based on the Text Edited by Muhsin Mahdi: Contexts, Criticism. 1990 & 1995. A Norton Critical Edition. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010.

- Miquel, André. Un Conte des Mille et Une Nuits: Ajîb et Gharîb (Traduction et perspectives d’analyse). Paris: Flammarion, 1977.

- Miquel, André. Sept contes des Mille et Une Nuits, ou Il n’y a pas de contes innocents, suivi d’entretiens autour de Jamaleddine Bencheikh et Claude Brémond. Paris: Sindbad, 1981.

- Bremond, Claude, ed. Les Dames de Bagdad: Conte des Mille et une nuits. Trans. André Miquel / Claude Bremond, A Chraïbi, A. Larue, and M. Sironval. La Nébuleuse du conte: Essai sur les premiers contes de Galland. Paris: Desjonquères, 1991.

- Bencheikh, Jamel Eddine, and André Miquel, ed. Les Mille et Une Nuits: Contes choisis. Trans. Jamel Eddine Bencheikh, André Miquel & Touhami Bencheikh. 4 vols. Folio. Paris: Gallimard, 1991-2001.

- Bencheikh, Jamel Eddine, and André Miquel, trans. Les Mille et Une Nuits. 3 vols. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Paris: Gallimard, 2005-7.

- Album Mille et Une Nuits: Iconographie. Choisie et commentée par Margaret Sironval. Albums de la Pléiade, 44. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Paris: Gallimard, 2005.

- Lyons, Malcolm & Ursula, trans. The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights. Introduction by Robert Irwin. 3 vols. Penguin Classics Hardback. London: Penguin, 2008.

- Lyons, Malcolm & Ursula, trans. The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights. Volume 1: Nights 1 to 294. Introduction by Robert Irwin. 3 vols. 2008. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2010.

- Lyons, Malcolm & Ursula, trans. The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights. Volume 2: Nights 295 to 719. Introduced & Annotated by Robert Irwin. 3 vols. 2008. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2010.

- Lyons, Malcolm & Ursula, trans. The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights. Volume 3: Nights 719 to 1001. Introduction by Robert Irwin. 3 vols. 2008. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2010.

- Lyons, Malcom C., trans. Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange. Introduction by Robert Irwin. Penguin Classics. 2014. London: Penguin Random House UK, 2015.

- Peña Martín, Salvador, trans. Mil y una noches. 4 vols. 2016. Madrid: Editorial Verbum, 2018.

- Seale, Yasmine, trans. Aladdin: A New Translation. Ed. Paulo Lemos Horta. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

- Seale, Yasmine, trans. The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights. Ed. Paulo Lemos Horta. Foreword by Omar El Akkad. Afterword by Robert Irwin. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021.

- Blyton, Enid. Tales from the Arabian Nights: Retold by Enid Blyton. Illustrated by Anne & Janet Johnstone. 1951. London: Latimer House, 1956.

- Bull, René, illus. The Arabian Nights. Children’s Classics. Bath: Robert Frederick, 1994.

- Ouyang, Wen-Ching, & Paulo Lemos Horta, ed. The Arabian Nights: An Anthology. Everyman’s Library 361. A Borzoi Book. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014.

- Pinson, R. W., ed. Märchen aus 1001 Nacht: Die berühmten Geschichten aus dem Morgenland. Selected by G. Blau, A. Horn & R. W. Pinson. 1979. Bindlach: Gondrom Verlaf GmbH, 2001.

- Samsó, Julio, trans. Antología de Las Mil y Una Noches. Libro de Bolsillo: Clásicos 599. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1975.

- Scott, Anne, ed. Tales from the Arabian Nights. Retold by Vladimir Hulpach. Trans. Vera Gissing. Illustrated by Mária Zelibská. London: Cathay Books, 1981.

- Weber, Henry, ed. Tales of the East: Comprising the Most Popular Romances of Oriental Origin, and the Best Imitations by European Authors: with New Translations, and Additional Tales, Never Before Published: to which is prefixed an introductory dissertation, containing the account of each work, and of its author, or translator. 3 vols. Edinburgh: James Ballantyne, 1812.

-

Vol. I:

- The Arabian Nights [Galland (1704-17)]

- New Arabian Nights' Entertainments [Chavis & Cazotte (1788-89)] Vol. II:

- New Arabian Nights' Entertainments (cont.)

- Persian Tales [Pétis de la Croix (1710)]

- Persian Tales of Inatulla [Alexander Dow (1768)]

- Oriental Tales [A. C. P., Comte de Caylus (1749)]

- Nourjahad [Frances Sheridan (1767)]

- "Four Additional Tales from the Arabian Nights" [Caussin de Perceval (1806)] Vol. III:

- The Mogul Tales [Thomas-Simon Gueullette (1723)]

- Turkish Tales [Pétis de la Croix (1710)]

- Tartarian Tales [Thomas-Simon Gueullette (1723)]

- Chinese Tales [Thomas-Simon Gueullette (1723)]

- Tales of the Genii [James Ridley (1764)]

- History of Abdalla the Son of Hanif [Jean Paul Bignon (1713)]

- Wiggin, Kate Douglas & Nora A. Smith, eds. The Arabian Nights: Their Best-Known Tales. Illustrated by Maxfield Parrish. New York: Quality Paperback Book Club, 1996.

- Williams-Ellis, Amabel. The Arabian Nights Stories Retold. 1957. London: Blackie, 1972.

Arabic

Antoine Galland (1646-1715) – [12 vols: 1704-1717] (French)

Denis Chavis & Jacques Cazotte (fl. 1780s / 1719-1792) – [4 vols: 1788-89] (French)

Maximilian Habicht et al. (1775-1839) – [15 vols: 1824-25] (German)

Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall / Guillaume-Stanislas Trébutien / George Lamb (1774-1856 / 1800-1870 / 1784-1834) – [3 vols: 1826] (German / French / English)

Gustav Weil (1808-1889) – [4 vols: 1837-41] (German)

Henry Whitelock Torrens (1806-1852) – [1 vol: 1838] (English)

Edward William Lane (1801-1876) – [3 vols: 1839-40] (English)

John Payne (1842-1916) – [13 vols: 1882-89] (English)

Richard F. Burton (1821-1890) – [16 vols: 1885-88] (English)

Max Henning (1861-1927) – [24 vols: 1895-97] (German)

Andrew Lang (1844-1912) – [1 vol: 1898] (English)

Dr. J. C. Mardrus (1868–1949) – [16 vols: 1899-1904] (French)

Cary von Karwath (?) – [19 vols: 1906-14] (German)

Laurence Housman (1865-1959) – [4 vols: 1907-14] (English)

Enno Littmann (1875-1958) – [6 vols: 1921-28] (German)

Mikhail Alexandrovich Salye (1899-1961) – [8 vols: 1929-36] (Russian)

Francesco Gabrieli (1904-1996) – [4 vols: 1948] (Italian)

Arthur John Arberry (1905-1969) – [1 vol: 1953] (English)

Rafael Cansinos-Asséns (1882-1964) – [3 vols: 1954-55] (Spanish)

Nessim Joseph Dawood (1927-2014) – [2 vols: 1954-57] (English)

René R. Khawam (1917-2004) – [7 vols: 1965-67 & 1985-88] (French)

Felix Tauer (1893-1981) – [8 vols: 1928-34] (Czech & German)

Husain Haddawy (?) – [2 vols: 1990-95] (English)

Jamel Eddine Bencheikh & André Miquel (1930-2005 / 1929- ) – [10 vols: 1977-2001 & 2005-7] (French)

Prof. Malcolm C. & Dr. Ursula Lyons (1929-2019 / ?-2016) – [3 vols: 2008] (English)

Salvador Peña Martín (1958- ) – [4 vols: 2016] (Spanish)

Yasmine Seale (1989- ) – [2 vols: 2019-2021] (English)

Miscellaneous

- Abou-Hussein, Hiam & Charles Pellat. Cheherazade: Personage Littéraire. Algiers: Société Nationale d’Édition et de Diffusion, 1976.

- Ali, Muhsin Jassim. Scheherazade in England: A Study of Nineteenth-Century English Criticism of the Arabian Nights. Washington: Three Continents Press, 1981.

- Baroud, Mahmoud. The Shipwrecked Sailor in Arabic and Western Literature: Ibn Tufail and His Influence on European Writers. London & New York: I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2012.

- Bencheikh, Jamel Eddine. Les Mille et une Nuits ou la parole prisonnière. Bibliothèque des Idées. Paris: Gallimard, 1988.

- Bencheikh, Jamel Eddine, Claude Bremond and André Miquel. Mille et un Contes de la Nuit. Bibliothèque des Idées. Paris: Gallimard, 1991.

- Campbell, Kay Hardy, Ferial J. Ghazoul, Andras Hamori, Muhsin Mahdi, Christopher M. Murphy, & Sandra Naddaff. The 1001 Nights: Critical Essays and Annotated Bibliography. Mundus Arabicus 3. Cambridge, Mass.: Dar Mahjar, 1983.

- Caracciolo, Peter L., ed. The Arabian Nights in English Literature: Studies in the Reception of The Thousand and One Nights into British Culture. London: Macmillan, 1988.

- Chauvin, Victor. Bibliographie des ouvrages arabes ou relatifs aux arabes publiés dans l’Europe chrétienne de 1810 à 1885. 12 vols. Liège: H. Vaillant-Carmanne, Leipzig: O. Harrassowitz, 1892-1922.

- Vol. 1: Préface (pp. v-xxxix). 1892.

- Vol. 2: Kalîlah. 1897.

- Vol. 3: Louqmâne et les Fabulistes. Barlaam. Antar et les Romans de chevalerie. 1898.

- Vol. 4: Les 1001 Nuits (1ere partie). 1900.

- Vol. 5: Les 1001 Nuits (2ème partie). 1901.

- Vol. 6: Les 1001 Nuits (3ème partie). 1902.

- Vol. 7: Les 1001 Nuits (4ème partie). 1903.

- Vol. 8: Syntipas. 1904.

- Vol. 9: Recueils Orientaux. (pp. 57-95). 1905.

- Vol. 10: Table des Matières. (pp. 145-46). 1907.

- Chauvin, Victor. La Récension Égyptienne des Mille et Une Nuits. Bruxelles: Office de Publicité / Société Belge de Librairie, 1899.

- Chebel, Malek. Psychanalyse des Mille et Une Nuits. 1996. Petite Bibliothèque Payot. Paris: Editions Payot & Rivages, 2002.

- Diyāb, Hannā. The Book of Travels. Trans. Elias Muhanna. Foreword by Yasmine Seale. Introduction by Johannes Stephan. Afterword by Paulo Lemos Horta. Library of Arabic Literature, 87. 2021. New York: New York University Press, 2022.

- Eliséef, Nikita. Thèmes et motifs des Mille et Une Nuits: Essai de Classification. Beirut: Institut Français de Damas, 1949.

- Gerhardt, Mia I. The Art of Story-Telling: A Literary Study of the Thousand and One Nights. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1963.

- Ghazoul, Ferial Jabouri. The Arabian Nights: A Structural Analysis. Cairo: Cairo Associated Institution for the Study and Presentation of Arab Cultural Values, 1980.

- Ghazoul, Ferial J. Nocturnal Poetics: The Arabian Nights in Comparative Context. Cairo : The American University in Cairo Press, 1996.

- Hamori, Andras. On the Art of Medieval Arabic Literature. 1974. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- Horta, Paulo Lemos. Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2017.

- Irwin, Robert. The Arabian Nightmare. 1983. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988.

- Irwin, Robert. The Arabian Nights: A Companion. London: Allen Lane, 1994.

- Kilito, Abdelfattah. L’oeil et l’aiguille: Essai sur “les mille et une nuits.” Textes à l’appui: série islam et société. Paris: Editions la Découverte, 1992.

- Lahy-Hollebecque, Marie. Schéhérazade ou L’éducation d’un Roi. 1927. Collection Destins de Femmes. Paris: Pardès, 1987.

- Lane, E. W. Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians. 1836. Ed. E. Stanley Poole. Everyman’s Library 315. London: Dent, New York: Dutton, 1963.

- Larzul, Sylvette. Les Traductions Françaises des Mille et Une Nuits: Études des versions Galland, Trébutien et Mardrus. Précédée de “Traditions, traductions, trahisons,” par Claude Bremond. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Muslim Discovery of Europe. 1982. London: Phoenix, 1994.

- Lynch, Enrique. La Lección de Sheherazade. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama, 1987.

- Mahdi, Muhsin. The Thousand and One Nights. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1995.

- Marzolph, Ulrich, & Richard van Leeuwen, with the assistance of Hassan Wassouf, ed. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. 2 vols. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

- Marzolph, Ulrich, ed. The Arabian Nights Reader. Series in Fairy-Tale Studies. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 2006.

- May, Georges. Les Mille et une nuits d’Antoine Galland, ou le chef d’oeuvre invisible. Paris: P.U.F., 1986.

- Naddaff, Sandra. Arabesque: Narrative Structure and the Aesthetics of Repetition in the 1001 Nights. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991.

- Nicholson, Reynold A. A Literary History of the Arabs. 1907. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1969.

- Pinault, David. Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights. Studies in Arabic Literature 15. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1992.

- Ranelagh, E. J. The Past We Share: The Near Eastern Ancestry of Western Folk Literature. London: Quartet, 1979.

- Sallis, Eva K. Sheherazade through the Looking Glass: The Metamorphosis of the Thousand and One Nights. Curzon Studies in Arabic and Middle Eastern Literatures. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1999.

- Von Grunebaum, Gustave E. Medieval Islam: A Study in Cultural Orientation. 1946. Phoenix Books 69. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Weber, Edgard. Imaginaire Arabe et Contes Erotiques. Collection Comprendre le Moyen-Orient. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan, 1990.

•