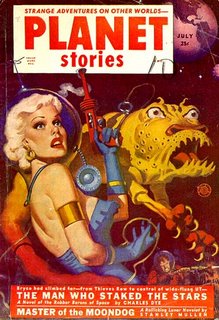

Planet Stories (July 1952) -- Philip K. Dick's first published story, "Beyond Lies the Wub" appeared in this issue (though it isn't mentioned on the cover ... I take it that lobster thing is meant to be a moondog rather than a wub).

Planet Stories (July 1952) -- Philip K. Dick's first published story, "Beyond Lies the Wub" appeared in this issue (though it isn't mentioned on the cover ... I take it that lobster thing is meant to be a moondog rather than a wub).When Tina Shaw and I were kicking around suggestions for a book we could do together last year, one of the ideas that came up was for an historical anthology of New Zealand Science Fiction. In fact, we ended up editing a collection of contemporary stories about myth instead (due out from Reed in late 2006 -- watch this space), but it still seems to me quite an interesting project.

Now John Dolan writes to say that he's writing an essay on what has (inevitably), to be called NZSF. I don't in the least grudge him his priority. In fact, I'm very curious to see what he makes of it. I hope he's not too unkind to them, though, our pioneering SF writers -- they are, after all, "ours, by God, / peculiarly by virtue of whatever was / held in common with other colonies." (Kendrick Smithyman, "Research Project").

Yes, I mean, how different can a specifically New Zealand SF actually be? Ours ... by virtue of whatever was held in common with other -- in this case pulpy scribblers about Androids and Rockets and Mars and the Future and Alternate History, etc. etc.

I don't know. It would have been interesting to speculate about it. My first impression is that SF has always had slightly more of a high culture cachet in NZ than elsewhere. A surprising number of so-called "serious" writers have tried their hand at it here. I drew up a list of the ones who were most interesting to me at the time, though it could undoubtedly be updated and expanded:

Samuel Butler (1835-1902) Erewhon; or Over the Range (1872)

Erewhon Revisited (1901)

Julius Vogel (1835-1899) Anno Domini 2000; or, Woman's Destiny (1889)

M. K. Joseph (1914-1981) The Hole in the Zero (1967)

The Time of Achamoth (1977)

Maurice Gee (b.1931) Under the Mountain (1979)

The World Around the Corner (1980)

The Halfmen of O (1982)

The Priests of Ferris (1984)

Motherstone (1985)

Margaret Mahy (b.1936) The Catalogue of the Universe (1985)

Aliens in the Family (1986)

The Tricksters (1986)

The Door in the Air and Other Stories (1988)

Dangerous Spaces (1991)

(TV miniseries) Typhon’s People (1994)

A Dissolving Ghost: Essays and More (2000)

Alchemy (2002)

Maddigan’s Quest (2006)

Craig Harrison (b.1942) Tomorrow Will Be a Lovely Day (1975)

Broken October (1976)

The Quiet Earth (1981)

Days of Starlight (1988)

Phillip Mann (b.1942) The Eye of the Queen (1982)

Master of Paxwax: Book One of the Story of Pawl Paxwax, the Gardener (1986)

The Fall of the Families: Book Two of the Story of Pawl Paxwax, the Gardener (1986)

Pioneers (1988)

Wulfsyarn: A Mosaic (1990)

A Land Fit for Heroes. 4 Vols (1994-1996)

Michael Morrissey (b.1942) The Fat Lady & The Astronomer: Some Persons, Persuasions, Paranoias, and Places You Ought to Encounter (1981)

(ed.) The New Fiction (1985)

Octavio’s Last Invention (1991)

Paradise to Come (1997)

Mike Johnson (b.1947) Lear: the Shakespeare Company Plays Lear at Babylon (1986)

Anti Body Positive (1988)

Lethal Dose (1991)

Dumb Show (1996)

Counterpart (2001)

Stench (2004)

Hugh Cook (b.1956) (10 vols) Chronicles of an Age of Darkness (1986-. )

Phillip Mann wrote a very useful entry about it for The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature, ed. Roger Robinson & Nelson Wattie (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998) 481-83.

My introductory essay didn't really get very far. To be honest, I'm really more interested in trying to write Science Fiction than in writing about it. I suppose I hoped that the two interests might fruitfully overlap -- hence my opening question:

Night in the City:

Strange Days in NZ sf

How does one actually go about writing a science fiction novel?

In a 1964 letter to his close friend, Ron Goulart, the appallingly prolific (and intermittently brilliant) Philip K. Dick explained how he wrote one:

this is how PKD gets 55,00 words (the adequate mileage) out of his typewriter: by having 3 persons, 3 levels, 2 themes (one outer or world-sized, the other inner or individual sized), with a melding of all, then, at last, a humane final note. [Quoted from Lawrence Sutin, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick (1989): 138].

The three characters should be, respectively:

· “First character, not protagonist but … less than life, a sort of everyman who exists throughout book but is, well, passive; we learn the entire world or background as we see it acting on him”;

· “In Chapter Two comes the ‘protag,’ who gets a two-syllable name such as ‘Tom Stonecypher,’ as opposed to the monosyllabic ‘Al Glunch’ tag for the Chapter One ‘subman’”;

· “through Mr. S’s eyes and ears, we glimpse for the first time … superhuman reality – and the human being, shall we call him Mr. Ubermensch? Who inhabits this realm.”

So, “just as Mr G. is the taxpayer and Mr S. is the ‘I,’ the median person, Mr. U is Mr. God, Mr. Big” – the plot development of the book is based on blending the original personal dilemma (“marital problems or sex problems or whatever it is”) of Mr. S with the worldwide “Atlas weight” problems faced by Mr. U, until:

The terminal structural mechanism is revealed: THE PERSONAL PROBLEM OF MR. S IS THE PUBLIC SOLUTION FOR MR. U. And this can occur whether Mr. S is with or pitted against Mr. U.

It all sounds a bit mechanical, and certainly helps to explain how Dick managed to churn out eleven novels in two years, but when one adds that among them were classics such as Martian Time-Slip, Now Wait for Last Year, Dr Bloodmoney, The Simulacra, and Clans of the Alphane Moon, one has to acknowledge that there may be something to be said for such formulaic blueprints after all. Possibly the most disconcerting of them all, however, was The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, which depicts an invasion of Earth by some kind of Gnostic demiurge who has taken on the form of the slit-eyed, prosthetic-handed, steel-jawed Terran entrepreneur, Palmer Eldritch ...

I'm still very interested in that Phil Dick prescription for how to write a novel, but wresting it around to a discussion of specifically NZ themes was undoubtedly going to be a bit of a chore. So I had go at a different kind of beginning to the essay ...

At the end of his fifties post-nuclear holocaust novel The Chrysalids, John Wyndham’s telepathic characters are making their way to a remote haven in the South Seas called something like “Sealand.” That tends to be it for New Zealand in classic Golden Age Sf: a place sufficiently remote for civilisation to survive there after the devastation of Europe, Asia and America ...

With the advent of the new wave, though, psychological factors began to become primary within a genre previously dominated by space opera and hard science (Ursula Le Guin’s “fiction for young engineers”).

I’m not proposing to write a history of NZ’s involvement with Sf here - that would be a bit beyond my scope, but just to talk about some interesting (and otherwise almost inexplicable) texts which that tradition has thrown up.

.... And so on to talk about Mike Johnson's Lear, Phillip Mann's Pioneers, and a few other eccentric (and therefore strangely characteristic) NZ SF classics.

Well, that's as far as I got with the idea, anyway. It's interesting how many of these writers have been transplanted Brits, for one thing ... Anyway, over to you, John.

No comments:

Post a Comment