The Works of George Borrow: Edited with Much Hitherto Unpublished Manuscript. Ed. Clement Shorter. Norwich Edition (limited to 775 copies). 16 vols. London: Constable & Co. Ltd. / New York: Gabriel Wells, 1923-24.

- The Bible in Spain: or the Journey, Adventures, and Imprisonment of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula (1843)

- The Bible in Spain [vol. 2]

- Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest (1851)

- Lavengro [vol. 2]

- The Romany Rye (1857)

- The Romany Rye [vol. 2]

- The Songs of Scandinavia, and Other Poems & Ballads (1829)

- The Songs of Scandinavia [vol. 2]

- The Songs of Scandinavia [vol. 3]

- The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies in Spain (1841)

- Romano Lavo-Lil: A Wordbook of the Anglo-Romany Dialect (1874)

- Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery (1862)

- Wild Wales [vol. 2]

- Wild Wales [vol. 3]

- Miscellanies [vol. 1]

- Miscellanies [vol. 2]

Does this set of books remind you of anything? Probably not. After all, this is quite an unusual juxtaposition of authors - and texts:

The Works of Herman Melville. Ed. Raymond Weaver. 16 vols. London: Constable, 1922-24.Same publisher. Same number of volumes. Roughly the same date of publication, and (at the time, at least), almost the same degree of obscurity.

- Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846)

- Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847)

- Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849)

- Mardi [vol. 2]

- Redburn: His First Voyage (1849)

- White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War (1850)

- Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851) [1]

- Moby-Dick [vol. 2]

- Pierre; or, The Ambiguities (1852)

- Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855)

- The Piazza Tales (1856)

- The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857)

- Billy Budd and Other Prose Pieces (1924)

- Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876)

- Clarel [vol. 2]

- Poems (1924)

Of course we now know that this same edition of Melville - the first to collect all of his disparate works (including "Billy Budd", published here for the first time) - would lead directly to the Melville revival, that swelling chorus of interest, appreciation, and (eventually) obsession which would culminate in crowning him one of the world's great authors.

I've written more about this process here.

But what of George Borrow? No such luck, I'm afraid. His mid-nineteenth-century vogue, based principally on that swashbuckling travel yarn The Bible in Spain (1843) - just as Melville's was on Typee (1846) - grew into something of a cult among readers of his distinctly less bestselling autobiographical novels Lavengro (1851) and The Romany Rye (1857).

He even reached the level of being mocked and parodied by the frontrunner of a new wave of popular fiction writers, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in his 1913 short story "'Borrow'-ed Scenes":

"It cannot be done. People really would not stand it. I know because I have tried." — Extract from an unpublished paper upon George Borrow and his writings.

Doyle's rather malicious story portrays the misadventures of a deluded fan who attempts to go about the countryside behaving like the semi-autobiographical protagonist of Borrow's books: accosting Gypsies with snatches of Romany, offering to fist-fight unruly tinkers, and attempting to impress barmaids with his high-flown patter.

Naturally the results are not good. But then anyone who set out to cross America using the methods of Jack Kerouac's similarly semi-autobiographical spokesman "Sal Paradise" from On the Road would hardly fare much better ...

What then, in the Victorian era, seemed bizarre: the deliberate fabrication of a "travel persona" to act as your print protagonist, is now commonplace. The "Bruce Chatwin" or "Bill Bryson" of the travel books resemble only in part those actual individuals.

Travel literature, though it continues to be shelved under "non-fiction" in libraries and bookshops, has always contained a good deal of more-or-less true, or grotesquely exaggerated, or even downright invented material.

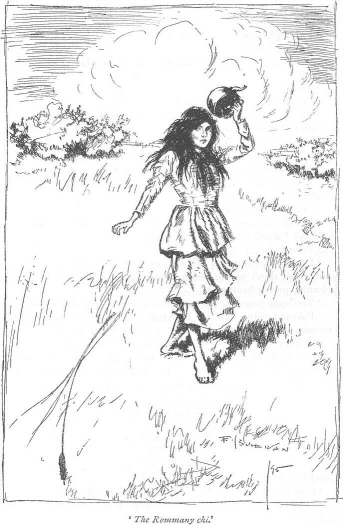

Melville had the same problem with his own early works. People simply could not get it through their heads that his first book Typee was a novelised version of reality, not a direct transcript of events. So beguiled were they with the winsome Fayaway, from that far-off cannibal valley in the Marquesas Islands (as you can see from the illustration above, her appeal, in the buttoned-up United States of the mid-nineteenth century, is not so terribly hard to fathom), that Melville became, overnight, a kind of sex symbol.

The trouble was that whatever Melville was (and he himself never seemed quite sure), it certainly wasn't that. He was a very much stranger proposition: more of a forerunner of Kafka or Borges than an American avatar of Victor Hugo.

I've written quite a lot about Melville on this blog (and elsewhere): about his poetry; about the claims of Moby-Dick to be considered that mythical beast, the Great American Novel; also about the trials and tribulations of his principal biographer, Hershel Parker. However, I've never written about George Borrow before, despite my early exposure to his works in the form of the beguiling and bewildering Lavengro.

Why is that? I suppose because despite the obvious parallels between the two, the differences are perhaps even more striking. To put it simply, Borrow never wrote a Moby-Dick or a "Bartleby." Nor, unfortunately, do his posthumous papers appear to contain any lurking parallels to Billy Budd: just piles and piles of poems and ballads in translation.

His fanatical anti-Catholicism is a bit offputting, too - and there's something rather un-English about his boastful self-vaunting and his obvious pride in his own linguistic and literary accomplishments. One can't help feeling, though, that if he had written in a country more in need of literary heroes, as America certainly was in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, that he might have carved out more of a place in the pantheon for himself.

Melville too (dare one say it) has his faults. There's a laborious jocularity in many of his short stories, for instance, which robs them of their full effect. Even the very best of them, "Bartleby," is nearly ruined at the last minute by that add-on information about the "Dead Letter Office." Pierre may have been unjustly criticised at the time for its challenging theme of emotional incest, but even one of his greatest admirers, Hershel Parker, has taken it upon himself to "improve" it by removing the bitter middle section about Pierre's misadventures as an author:

Borrow, let's state it plainly, is no Melville. He operates on a distinctly different plane than that. But his charms and accomplishments as an author are many.

Or so (at least) it appears to me. The wikipedia entry on his 1862 travel book Wild Wales describes his narrative voice as "distinctive and at times a little overbearing," and complains that he "never returned to deepen his knowledge and failed to cover the many parts of Wales he left out of this work." I suppose that few books cover the many things they were forced to leave out, when you really think about it.

My suspicion that the author of this entry must be a disgruntled native Welshman is deepened by the following passage:

The author makes much of his self-taught ability to speak the Welsh language and how surprised the native Welsh people he meets and talks to are by both his linguistic abilities and his travels, education and personality, and also by his idiosyncratic pronunciation of their language.I suspect I would feel much the same if I were forced to read the peregrinations of some Sassenach bigmouth through the Scottish Highlands, but since I have no such emotional link to Wales, I'm able to interpret this particular work as quite readable and charming. I can, however understand why this particular page has not one but two notices on it for "imprecise citations" and "importation of original research"!

Borrow, then, is definitely an acquired taste. I fear that I acquired it long ago, when I first picked up a copy of Lavengro in a local secondhand shop. Even now I can't look through its pages without having my spirits lifted: it seems so alive still.

You may not have the same experience, mind you. He is odd, a very eccentric (and egocentric) writer. But then I'm reliably informed that there are many who are impervious to the charms of Melville, too - who can't get past the first page of Moby-Dick, and don't see what all the fuss is about "Billy Budd." I defy them to say that of "Bartleby," though.

The experience of reading Borrow for the first time is (dare I say it) a little like that morning walk in the country taken by the eponymous hero of Withnail and I. As he ruefully concludes, the terrifying locals he encounters are not at all like the denizens of the H. E. Bates novel he's been reading. They're something stranger, darker - and funnier - altogether.

-

Collected Works:

- The Works of George Borrow, Edited with Much Hitherto Unpublished Manuscript. Ed. Clement Shorter. Norwich Edition. No. 533 of 775. 16 vols. London: Constable & Co. Ltd. / New York: Gabriel Wells, 1923-24.

- The Bible in Spain: or the Journey, Adventures, and Imprisonment of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula (1843) [1]

- The Bible in Spain [2]

- Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest (1851) [1]

- Lavengro [2]

- The Romany Rye (1857) [1]

- The Romany Rye [2]

- The Songs of Scandinavia, and Other Poems and Ballads (1829) [1]

- The Songs of Scandinavia [2]

- The Songs of Scandinavia [3]

- The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies in Spain (1841)

- Romano Lavo-Lil: A Wordbook of the Anglo-Romany Dialect (1874)

- Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery (1862) [1]

- Wild Wales [2]

- Wild Wales [3]

- Miscellanies [1]

- Miscellanies [2]

- The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies of Spain. 1841. London: John Murray, 1908.

- The Bible in Spain: or, The Journeys, Adventures, and Imprisonments of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula. 1843. Ed. Ulick Ralph Burke. London: John Murray, 1912.

- Lavengro: The Scholar, The Gypsy, The Priest. 1851. Illustrated by Claude A. Shepperson. Introduction by Charles E. Beckett. London: The Gresham Publishing Co. Ltd., n.d.

- Lavengro: The Classic Account of Gypsy Life in Nineteenth-Century Britain. 1851. Rev. ed. 1900. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1991.

- The Romany Rye. 1857. The Nelson Classics. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., n.d.

- Wild Wales. 1862. Introduction by Brian Rhys. The Nelson Classics. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., n.d.

- Romano Lavo-Lil: A Wordbook of the Anglo-Romany Dialect (1874)

- Tales of the Wild and Wonderful (London: Hurst, Robinson, and Co., 1825)

- Klinger, Friedrich Maximilian. Faustus, his Life, Death and Descent into Hell. 1791 (Norwich: W. Simpkin and R. Marshall, 1825)

- Romantic Ballads, Translated from the Danish; and Miscellaneous Pieces (Norwich: S. Wilkin / London: John Taylor / Wightman and Cramp, 1826)

- The Talisman: From the Russian of Alexander Pushkin, with Other Pieces (St Petersburg: Schulz and Beneze, 1835)

- Targum, or Metrical Translations from Thirty Languages and Dialects (St Petersburg: Schulz and Beneze, 1835)

- [with Stepan Vaciliyevich Lipovtsov] The Manchu New Testament (St Petersburg: The British and Foreign Bible Society, 1835)

- The Gypsy Luke [Embéo e Majaró Lucas] (1837)

- Wyn, Elis. The Sleeping Bard, or Visions of the World, Death and Hell. Translated from the Cambrian British (London: John Murray, 1860)

- The Turkish Jester; or, The Pleasantries of Cogia Nasr Eddin Effendi. Translated from the Turkish (Ipswich: W. Webber, 1884)

- Ewald, Johannes. The Death of Balder: From the Danish (London: Jarrold & Sons, 1889)

- Translations. Ed. Thomas J. Wise. 42 vols (Privately Printed, 1913-14)

- Ballads of All Nations: A Selection. 1826, 1835, 1913, 1923. Ed. R. Brimley Johnson from the Texts of Professor Herbert Wright (London: Alston Rivers Ltd., 1927)

- Jenkins, Herbert. The Life of George Borrow: Compiled from Unpublished Official Documents. His Works, Correspondence, etc. London: John Murray,

- Knapp, William I. Life, Writings, and Correspondence of George Borrow (1803-1881). Derived from Official and Other Authentic Sources. Vol. 1 of 2. London: John Murray, 1899. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University Library. Web. 13 May 2020.

- Knapp, William I. Life, Writings, and Correspondence of George Borrow (1803-1881). Derived from Official and Other Authentic Sources. Vol. 2 of 2. London: John Murray, 1899. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University Library. Web. 13 May 2020.

- Shorter, Clement. George Borrow and His Circle: Wherein May Be Found Many Interesting Unpublished Letters of Borrow and His Friends. London and New York: Hodder and Stoughton, 1913. Internet Archive. Contributed by Cornell University Library. Web. 13 May 2020.

- Thomas, Edward. George Borrow, the Man and His Books. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912. Project Gutenberg. Web. 15 May 2020.

- Williams, David. A World of His Own: The Double Life of George Borrow. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Wise, Thomas J. A Bibliography of the Writings in Prose and Verse of George Henry Borrow. London: Richard Clay & Sons, 1914. Internet Archive. Contributed by Cornell University Library. Web. 15 May 2020.

Books:

Translations:

Secondary:

No comments:

Post a Comment