I guess this is more or less the image the words "Arabian Nights" convey - gorgeous, scantily clad girls and muscular warriors; kings and commoners; Imams and slaves:

Certainly Richard F. Burton was no stranger to this orientalising tendency. His travel books are full of racist rantings about the laziness and general hopelessness of Blacks and Arabs. But then, he wasn't much more complimentary about Oxford Dons, Colonial Office officials, or any other ignoramuses who got in his way. He was a very angry, relentlessly curious, incurably opinionated man.

Despite all the many, many books he wrote - including travel classics such as his Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al Madinah & Meccah (1855-56) or The Lake Regions of Central Africa (1860) - it's his sixteen-volume translation of the 1001 Nights (or, as he called it, The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night) which will survive him. It is, in its strange way - a way almost as strange as the man who wrote it - a kind of masterpiece.

It's certainly a book that you either love or hate. At the moment, hatred appears to be in the ascendant. Marina Warner's recent book Stranger Magic: Charmed States & The Arabian Nights (2011) scarcely mentions it except to denigrate it by comparison with Burton's distinguished predecessors Antoine Galland and William Lane. She is forced to rely instead on a recent complete French translation of the Nights for much of her information about the book.

And in many ways this is fair enough. Even his strongest supporters would have to acknowledge that Burton's prose is bizarrely archaic and (at times) almost incomprehensibly eccentric. His verse - not a single one of the thousand-odd poems that throng the work is omitted - is, if anything, worse. What good is a translation that is almost impossible to read?

Then there are his footnotes. These are justly famous as a compendium of anthropological detail about the East, gathered over decades of wanderings through its many regions. Some of them are, admittedly, smutty (learned disquisitions on the sizes of the "organs" of different races; reams of information on clitorectomy and the various ways of making eunuchs), but I guess some of their shock value has worn off since 1885, when the ten volumes that constitute the translation proper first appeared.

It's not an easy read - nor was it ever meant to be. You almost need to learn a new language, Burton-ese, a weird amalgam of The Anatomy of Melancholy and Motteux and Urquhart's seventeenth-century translation of Rabelais, seasoned with a dash of Robert Browning, to understand him. But that's not an impossible task. It gets easier with practice, and the rewards are considerable. It's no accident that it was Jorge Luis Borges' favourite book (not to mention the praise lavished on it by Japanese novelist Junichiro Tanizaki). Like Edgar Allan Poe, Burton has a tendency to appeal more to non-native speakers of English than to his own more constipated countrymen.

The other great advantage to reading Burton in full is the immense apparatus of appendices, supplemental volumes, extra stories, and miscellaneous information about folklore and history which dominates (especially) the last six volumes of his translation, the so-called Supplemental Nights.

NB: Some reprints include seven supplementary volumes rather than the original six, but this is simply because volume XIII, containing the original versions of Galland's so-called "orphan stories" (including "Aladdin" and "Ali Baba") is so vast that it has seemed (at times) to make more sense to split it in two. There is otherwise no difference between the 16 and 17 volume editions - though certain of the twentieth-century Burton Club reprints, in the interests of reducing the size of their own volume 13, leave out Burton's lengthy literal translation of Galland's "Aladdin", preferring to include only his translation of the then recently discovered Arabic text (now, alas, generally regarded as anterior to Galland's, rather than as the original source of his French version).

Another accusation which has been levelled at Burton's Nights is the contention that much of his version was plagiarised from John Payne's 9-volume edition of 1882-84 (supplemented with four extra volumes of material, which roughly accord with Burton's volumes 11-13).

Burton himself makes no secret of his reliance on Payne's translation. He remarks of it, somewhat disarmingly:

I cannot but feel proud that he has honoured me with the dedication of "The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night." His version is most readable: his English, with a sub-flavour of the Mabinogionic archaicism, is admirable; and his style gives light and life to the nine volumes whose matter is frequently heavy enough. He succeeds admirably in the most difficult passages and he often hits upon choice and special terms and the exact vernacular equivalent of the foreign word, so happily and so picturesquely that all future translators must perforce use the same expression under pain of falling far short [my italics]. (Burton, 1885, 1: xiii)

While it's true that, in later life, John Payne (himself a notoriously testy individual) took to complaining about the liberties Burton had taken with his text - to wit, the wholesale copying of great swathes of it - a brief consultation of his version (which has recently, for some odd reason, been reprinted in full by Borders Bookshop in their classics series) might suggest to you that the truth is somewhat more complex than that.

For a start, Burton has revised all the transliterations of Arabic names - in itelf a not inconsiderable task. For another thing, Payne's somewhat convoluted verse translations have all been altered into infinitely more convoluted and strange "poems" by Burton (in fact, where a verse has been repeated exactly from an earlier volume, Burton sometimes quotes Payne's very different translation of it for variety).

Finally, great though Payne's command of Arabic and other Eastern languages undoubtedly was, he seldom left London, and it's a little hard to believe that his text couldn't be tweaked in some small respects by the famous traveller who managed to travel to Mecca undetected, passing as a native. As to that, though, Payne himself remarked, in a footnote to his 1898 translation of the quatrains of Omar Khayyam:

Capt. Burton's knowledge of literary Arabic, the qualification most needed for the successful accomplishment of the task in question, was, (as he himself, like the high-minded and honourable man he was, freely admitted on becoming acquainted with my work,) much inferior to my own and consequently his translation, and especially that part in which, as above stated, he had not the advantage of being able to guide himself by my previous version, is far less accurate than mine. No one is of course exempt from liability to error and mistakes must of necessity occur in the translation of an excessively difficult work like the Nights, executed pioneer-fashion, without any kind of assistance and at a time when Arabic dictionaries were both rare and miserably incomplete; but I have no hesitation in asserting, without fear of authoritative contradiction, that ... for every mistake which can be discovered in my work, it were easy to point out at least a dozen in those of Lane and Burton.

He went on to promise "as a curious chapter of literary history, the detailed story of my translation of the Nights and of the desperate and unscrupulous efforts of certain cliques, whose interests it threatened, to suppress, or at least to crush, it, efforts which happily, thanks to some remnant of discernment on the part of the reading public, proved entirely futile; as well as of my connection with Sir Richard Burton and the circumstances which led him, consequently upon the brilliant success of my version, to undertake a new one on his own account." As far as I know, he never published this more detailed account of the matter. There is, however, a good deal of evidence about it in Payne-afficionado Thomas Wright's respective biographies of Richard Burton (1906) and John Payne (1919).

Having weighed up what has been said on both sides, I think it's clear that the deal Burton and Payne (allegedly) struck - that the latter would have priority in issuing his translation, in exchange for turning a blind eye to the benefit the former was able to derive from copying his "exact vernacular equivalents" to so many conundrums in the original Arabic - probably seemed like a better idea in 1882 than it did in 1888, when it had become clear that Burton's translation was going to continue to eclipse his predecessor's in popularity. Burton himself suggests one obvious reason why:

... the learned and versatile author bound himself to issue only five hundred copies, and "not to reproduce the work in its complete and uncastrated form." Consequently his excellent version is caviare to the general - practically unprocurable.

Burton, by contrast, issued a thousand sets of his own translation (they had to be privately published in order to avoid prosecution for obscenity). It was also issued commercially in a "castrated" version by his wife, Lady Burton, and (subsequently, in 1898) in a far less brutally abridged Library Edition.

The plain facts that Payne's supporters have to face are:

- Who on earth would prefer a translation whose prose is every bit as dreadful as Burton's own, but which lacks the benefit of his bizarrely erudite annotation?

- Payne's curious versions of Arabic names are even more obtrusive and difficult to read than Burton's more conventional transliterations.

- Payne also lacks some of Burton's more interesting features, such as retention of the internal rhymes characteristic of Arabic kunstprosa.

- Burton had the benefit, not just of Payne's guidance, but of Lane's, Scott's and Galland's, not to mention the various German translators who had traversed the same paths before him: "And here I hasten to confess that ample use has been made of the ... versions above noted, the whole being blended by a callida junctura into a homogeneous mass" (Burton, 1885, I:xiii).

As you can see from the above, Burton made no secret of his debt to Payne. No doubt he understated its extent, but there was certainly no concealment of it either in his preface or later on, in his famous (or infamous) "terminal essay", with its innumerable asides on points of detail to do with the Nights or Eastern culture generally.

The truth is, those who find Burton unreadable are unlikely to have any more success with Payne. If their two translations of the Arabian Nights run more closely together than might seem common in the work of completely independent scholars, the sad fact is that Burton was the principal beneficiary. Payne may have done more than his fair share of the work of translation, but there can be little doubt that Burton made up for it with all the extras contained in his own sixteen volumes (including a very valuable concordance of all then extant versions of the collection, compiled by W. F. Kirby, included in his tenth volume).

The Nights made Burton a rich man. it's hard to see how he could have completed his task in such record time without the pioneering work of Payne, but that doesn't alter the fact that it was still a worthwhile thing to do. There have been many excellent translations of the Arabian Nights since then, but none of them have aspired to equal - let alone surpass - Burton's matchless freight of notes and appendices. It wasn't, in fact, until 2008 that anyone even tried to publish another "complete" translation in English (see my review of Malcolm C. Lyon's three-volume Penguin Classics version here). Clear and elegant though it is, it lacks the textual and critical apparatus of the comparable versions in French, Italian and German.

Not even the recent appearance of Ulrich Marzolph and Richard van Leeuwen's 2-volume Arabian Nights Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA / Denver CO / Oxford, UK: ABC Clio, 2004), magisterial though it is, could be said to have definitively superseded Burton's Nights. There simply is no other source for much of the detail he provides: especially about the other translators and translations up to 1885 ...

He may have sounded like a belligerent madman at times, but he was a great scholar - and the most independent (albeit eccentric) of thinkers - for all that.

It's not particularly extensive, or packed with rareties, as you can see below. I have done my best to collect inexpensive reprints of as many as possible of his books, though - particularly those relating to Arabia and the Arabian Nights.

I. Original Works

- Burton, Richard F. Goa, and The Blue Mountains; or, Six Months of Sick Leave. 1851. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

His very first book: in it he began his lifelong habit of essentially presenting the contents of his notebooks wihout much ordering beyond the chronological ...

- Burton, Richard F. Sindh and The Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus with Notices of the Topography and History of the Province. 1851. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1992.

Still a valuable guidebook to the area, widely available in Indian bookshops.

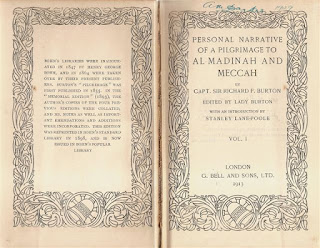

- Burton, Richard F. Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al Madinah & Meccah. 1855-56. Ed. Lady Burton. 1893. Bohn’s Library. 1898. 2 vols. London: G. Bell & Sons, 1913.

Lots of extras: maps, appendices, and so on, in this edition of the travel classic.

- Burton, Richard F. Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah. 1855-56. Intro. J. M. Scott. Geneva: Heron, n.d.

A more conventional reprint of the main text.

- Burton, Richard F. The Source of the Nile. The Lake Regions of Central Africa: A Picture of Exploration. 1860. Introduction by Ian Curteis. London: The Folio Society, 1993.

A very grumpy book. Burton could never get over the fact that the "unscientific" Speke was actually more-or-less right about the source of the White Nile, whereas he, with all his graphs and knowledge, was wrong. It didn't help that he'd been too ill to take part in that last side-expedition on their appallingly arduous trek together ...

- Burton, Richard F. The Gold-Mines of Midian [and the Ruined Midianite Cities: a Fortnight’s Tour in North-Western Arabia]. 1878. New York: Dover Publications, 1995.

Yet another one of Burton's get-rich-quick schemes - as unsuccessful as most of the others.

- Burton, Richard F. The Kasîdah of Hâjî Abdû el Yezdi: A Lay of the Higher Law. 1880. Booklover’s Library. London: Hutchinson, n.d.

Versified wisdom in the persona of a Middle-Eastern sage.

- Burton, Richard F. The Book of the Sword. 1884. New York: Dover Publications, 1987.

Very thorough - still indispensable to this day.

•

II. Translations

- Alf layla wa layla (c.8th-18th century)

- Burton, Richard F, trans. A Plain and Literal Translation of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, Now Entituled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: With Introduction, Explanatory Notes on the Manners and Customs of Moslem Men and a Terminal Essay upon the History of the Nights. 10 vols. Benares [= Stoke-Newington]: Kamashastra Society, 1885. N.p. [= Boston]: The Burton Club, n.d. [c.1900].

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Supplemental Nights to the Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night with Notes Anthropological and Explanatory. 6 vols. Benares [= Stoke-Newington]: Kamashastra Society, 1886-88. 7 vols. N.p. [= Boston]: The Burton Club, n.d. [c.1900].

One of the many, many reprints of the original form of Burton's translation, this one uses something close to the original plates, but has a very different binding and appearance (as well as being divided into 17 volumes instead of 16 - see the discussion of this slight anomaly in my introduction above).

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments. 1885. 10 vols. U.S.A.: The Burton Club, n.d. [c.1940s].

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Supplemental Nights to the Book of the Thousand and One Nights with Notes Anthropological and Explanatory. 1886-88. 6 vols. U.S.A..: The Burton Club, n.d. [c. 1940s].

This is a later facsimile, reset, but still almost identical in pagination to the original, except in the six volumes of Supplemental Nights, which have been more comprehensively rearranged. The binding is a very close echo of the 1885-88 original.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments. 1885. 3 vols. New York: The Heritage Press, 1934.

The first "complete" Burton I ever read. It reproduces the text of the ten volumes of his translation of the Nights proper, with elegant embellishments by Valenti Angelo. Well worth having.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, or The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night: A Selection of the Most Famous and Representative of these Tales. Ed. Bennett A Cerf. 1932. Introductory Essay by Ben Ray Redman. New York: Modern Library, 1959.

The first substantial commercially available one-volume selection from the whole work.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. A Plain and Literal Translation of the

Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, now entituled The Book of the Thousand

Nights and a Night: A Selection. Ed. P. H. Newby. 1950. London: Arthur Barker, 1953.

Rather a thin selection, but at least it includes a glossary of his more bizarre archaisms.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. More Stories from the Arabian Nights. Ed. Julian Franklyn. London: Arthur Barker, 1957.

Sequel to the former.

- Burton, Richard F. Love, War and Fancy: The Customs and Manners of the East from Writings on The Arabian Nights. Ed. Kenneth Walker. 1885. London: Kimber Paperback Library, 1964.

A very useful reprint of the more substantial notes and essays in Burton's translation. It was designed as a companion volume to the similar compendium of Lane's Notes to the Nights: Arabian Society in the Middle Ages (1883).

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Tales from the Arabian Nights: Selected from the Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night. Ed. David Shumaker. New York: Avenel Books, 1978.

A judicious and compendious selection.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Arabian Nights: The Marvels and Wonders of the Thousand and One Nights, Adapted from Richard F. Burton’s Unexpurgated Translation. Ed. Jack Zipes. Signet Classic. New York: Penguin, 1991.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Arabian Nights, Volume II: More Marvels and Wonders of the Thousand and One Nights, Adapted from Sir Richard F. Burton’s Unexpurgated Translation. Ed. Jack Zipes. Signet Classic. New York: New American Library, 1999.

Zipes has tried to get over the problem of Burton's English by rewriting and simplifying his prose. One can see the point, but the end result is neither fish nor fowl.

- Burton, Richard F., trans. Tales from 1001 Arabian Nights. 1885-1888. Ed. Ashwin J. Shah. 1992. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House, 1999.

Another substantial selection, intended principally for the Indian market.

- Basile, Giovanni Batiste. Il Pentamerone. Trans. Richard F. Burton. 1893. New York: Horace Liveright, 1932.

A beautiful reprint of Burton's translation, but lacking his preface and notes.

- Burton, Richard F. & Leonard C. Smithers, trans. The

Carmina of Gaius Valerius Catullus: Now first completely Englished into

Verse and Prose, the Metrical Part by Capt. Sir Richard F. Burton, K.

C. M. B., F. R. C. S., etc., etc. etc., and the Prose Portion,

Introduction, and Notes Explanatory and Illustrative by Leonard C.

Smithers. Preface by Lady Isabel Burton. London: Printed for the Translators, 1894.

An interesting, but not very mellifluous translation, one is forced to confess.

- Burton, Richard F., and F. F. Arbuthnot, trans. The Ananga Ranga of Kalyana Malla. 1885. London: Kimber, 1963.

Another "love manual" from ancient India.

- Nefzawi, Shaykh. The Perfumed Garden. Trans. Richard F. Burton. 1886. Ed. Alan Hull Walton. 1963. London: Panther, 1966.

More modern translators claim that Burton took appalling liberties with his original (which was, in any case, French - not Arabic). The very much fuller translation he is alleged to have made in his last years from the original Arabic text was burnt after his death by his widow.

- Nefzawi, Shaykh. The Glory of the Perfumed Garden: The Missing Flowers. An English Translation from the Arabic of the Second and Hitherto Unpublished Part of Shaykh Nafzawi’s Perfumed Garden. Trans. H. E. J. 1975. London: Granada, 1978.

A rather dodgy 'sequel' to Burton's translation, with a translator who won't even sign his name to it. Entertaining, though.

- Smithers, L. C. & Sir Richard Burton, trans. Priapeia sive diversorum poetarum in Priapum lusus, or Sportive Epigrams on Priapus by divers poets in English verse and prose. 1890. Wordsworth Classic Erotica. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Classics, 1995.

By now, it's clear that Burton had realised that translations of vaguely smutty ancient texts, with elaborate notes (generally compiled by his collaborators rather than himself), was the road to wealth - if not fame.

- Burton, R. F., trans. [Edward Retnisak]. Tales from the Gulistân, or Rose-Garden of the Sheikh Sa’di of Shirâz. 1888. London: Philip Allen, 1928.

And this book, though promulgated posthumously under his name, was not even translated by him, we've now been informed.

- Burton, Richard F. Vikram and the Vampire, or Tales of Hindu Devilry. 1870. Memorial Edition. Ed. Isabel Burton. London: Thylston & Edwards, 1893.

An early, very zesty, and unashamedly "written-up" version of the Indian tales.

- Burton, Richard F., and F. F. Arbuthnot, trans. The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. 1883. Ed. John Muirhead-Gould. 1963. London: Panther, 1968.

Still, probably, the most famous and widely available of Burton's works.

[Richard F. Burton: Arabian Nights (1885-88)]

[Richard F. Burton: Terminal Essay [Arabian Nights, vol. X} (1885)]

•

Giambattista Basile (c.1566–1632)

•

Gaius Valerius Catullus (c.84–c.54 BC)

•

Kalyana Malla (c.15th-16th century)

•

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Nafzawi [Sheikh Nefzawi] (c.12th Century)

•

Priapeia (c.1st Century B.C.)

•

Abū-Muhammad Muslih al-Dīn bin Abdallāh Shīrāzī [Saʿdī] (1184-c.1283/1291)

•

Śivadāsa (c.12th-14th century)

•

Mallanaga Vātsyāyana (c.4th-6th century)

•

III. Secondary Literature

- Blanch, Lesley. The Wilder Shores of Love. 1954. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1959.

This book offers a partial biography of Lady Burton rather than her husband, but he tends to dominate even so. Very entertaining, and a considerable bestseller in its day.

- Farwell, Byron. Burton: A Biography of Sir Richard Francis Burton. 1963. Harmondsworth: Viking, 1988.

The first substantial modern biography of Burton - now superseded in some respects, but still worth a read.

- Brodie, Fawn M. The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton. 1967. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

A beautifully written and well-researched piece of work. Still, in many ways, the most perspicacious of the various attempts to psychoanalyse Burton.

- Harrison, William. Burton and Speke. 1982. London: Star, 1985.

An entertaining and well written novel about the Nile expedition: the inspiration for the rather freer-with-the-facts film The Mountains of the Moon (1990).

- Rice, Edward. Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: The Secret

Agent Who Made the Pilgrimage to Mecca, Discovered the Kama Sutra, and

Brought the Arabian Nights to the West. 1990. New York: HarperPerennial, 1991.

A hugely detailed but, alas, somewhat credulous biography of Burton. Not really to be recommended, despite the fact that it contains a good deal of information not readily available elsewhere.

- McLynn, Frank. From the Sierras to the Pampas: Richard Burton’s Travels in the Americas, 1860-69. London: Century, 1991.

Excellent account of Burton's American travels: to the Mormons in Utah, the Highlands of Brazil, and the battlefields of Paraguay, among many other places.

- Ondaatje, Christopher. Sindh Revisited: A Journey in the Footsteps of Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton – 1842-1849: The India Years. Toronto: HarperCollins, 1996.

Excellent example of the "in the footsteps of" genre of travel writing.

- 'Ardonne, Marcus,' ed. The Secret Sutras: The ‘Lost’ Erotic Journals of Sir Richard Burton. London: New English Library, 1996.

A rather silly, tongue-in-cheek attempt to forge some secret "erotic" diaries for the great explorer. Listed here for completeness' sake only.

- Lovell, Mary S. A Rage to Live: A Biography of Richard and Isabel Burton. 1998. London: Abacus, 1999.

An impressive attempt to sum up where we are now with Burton biography. Lovell is a good writer and an astute judge of character, witness her excellent biographies of Winston Churchill and Amelia Earhart (among others).

4 comments:

That's a bizarre coincidence. Just before coming here I was reading about the Black Stone of the Ka'ba and Burton's comment on some vandals:

"In the 11th century, a man allegedly sent by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah attempted to smash the Black Stone, but was killed on the spot, having caused only slight damage.[13] In 1674, according to Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, someone smeared the Black Stone with excrement so that "every one who kissed it retired with a sullied beard". The Shi'ite Persians were suspected of being responsible and were the target of curses from other Muslims for centuries afterwards, though explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton doubted that they were the culprits; he attributed the act to "some Jew or Greek, who risked his life to gratify a furious bigotry."

I was all ready to be upset on behalf of Jews or Greeks, but it seems he hated everyone equally.

Floored by this example bibliographic mania. You're (the good kind of) crazy, Jack!

Yes, that seems a pretty fair summary. Oxford University refused to lend him an important 1001 Nights manuscript during his work on the collection, so he included about forty pages of bile and hatred about Oxford and his Dons in the relevant volume of the Supplemental Nights -- that, and the section of "Reviewers Review'd" seem to contain the most concentrated examples of rage in the book ...

Vast post Jack! The only book I have here I think is that strange book with Plato's Symposium and the Ananga Ranga in paper back.

I haven't read it. But I am sure I've read the Symposium but I think that was when I was a teenager (via Russells history of Philosophy which I found very fascinating at the time)although I've studied various of Plato more recently). I cant recall it being about love. (Plato-Socrates were logicians or "sophists" more.) It is the erotic-romantic element here I think that must have got you going - I used to read every thing I could get by Ryder Haggard - a again as a teenager it seemed hugely erotic (I used to get really excited reading those books) in a way I am sure I couldn't experience it now as a 65 year old!

I found this site years ago through a search that led to your Shecherazade's Web.

Thanks for the post, and for the bibliography. I've never been sure if I've read the whole thing or not. It was quest of two or three years, where I scoured bookstores and libraries trying to collect all the loose ends. Eventually, I just gave up.

Post a Comment