Denis Villeneuve, dir.: Dune: Part One (2021)

Denis Villeneuve, dir.: Dune: Part One (2021)Dunes

"These memories, which are my life"

- Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited (1945)

I see that my old paperback copy of Dune is dated 1973. I think that I must have got it for my birthday in 1975, when I was just turning 13. It didn't disappoint. In fact, I think that next to The Lord of the Rings, it probably had the biggest influence on me of anything I'd read up to then.

Not that I found it flawless, even at the time. I found the italicised internal monologues by the main characters unnecessarily intrusive on the action, and I also found tedious the 'sayings' by each of these characters enshrined in quote marks at the opening of each chapter.

But, hey, those were small things beside the sheer fascination of Herbert's vision of planetary ecologies, his portrayal of the Fremen, and the tantalising glimpses he provided of an immensely complex galaxy-wide economy.

Dune Messiah was an unexpectedly depressing cold shower-bath of a sequel to the lush vistas of Dune - though it's definitely grown on me over the years - but Frank Herbert seemed to be back on planet-spanning form in its follow-up, Children of Dune.

I dutifully followed the saga through all its twists and turns in the next three sequels, until the ridiculously titled (though actually rather good) Chapter House Dune in 1985. Herbert died the year after it was published.

Dune, dir. & writ. David Lynch (based on the novel by Frank Herbert) - with Francesca Annis, Linda Hunt, Kyle MacLachlan, Everett McGill, Kenneth McMillan, Siân Phillips, Jürgen Prochnow, Patrick Stewart, Sting, Max von Sydow, Sean Young - (USA, 1984).By then, however, we'd entered the world of the movies. There were many rumours about the first Dune film before it came out. I think Sci-fi fans in general were most excited by the prospect of a Ridley Scott version, building on the artistry of his Alien and (in particular) Blade Runner triumphs.

I don't think anyone - or anyone in my circle, at any rate - knew about the Jodorowsky concept designs, or any of the other details of the rocky road that led to David Lynch's eventual De Laurentis-produced spectacular.

I wouldn't say that it was love at first sight. The movie was too campy and over-the-top for an SF-cinematic sensibility formed by Kubrick's 2001 and Scott's Blade Runner. Over time, however, I began to see that Lynch was a horse of a different colour. He saw Dune as a huge Italian melodrama, with a lush operatic score, and a massive cast of picturesque characters.

The wonderful visual inventiveness of his guild navigators and planet-dwarfing space-ships remains impressive. And, once I had learned to recalibrate my expectations, I found his relish for teaasingly gnomic lines ("A beginning is a very delicate time" - Princess Irulan; "We have worm-sign such as God has never seen" - Stilgar; "The sleeper must awaken" - Duke Leto; "Tell me of your homeworld, Usul" - Chani; "The Spice must flow!" - passim) a source of rich entertainment at each of many reviewings over the years.

Francesca Annis was a spectacularly beautiful Lady Jessica, Sean Young played Chani as a kind of slinky cat-woman, and Patrick Stewart as Gurney Halleck looked super-cool, as always. Kyle MacLachlan - well, what can you say? He seemed to be in training for Agent Cooper in Twin Peaks already, but then one doesn't go to Grand Opera for gritty realism.

Frank Herbert’s Dune, dir. & writ. John Harrison (based on the novel by Frank Herbert) – with William Hurt, Alec Newman, Saskia Reeves, Susan Sarandon, Daniela Amavia – (USA, 2000)There were, of course, omissions. Putting so large a plot into one movie required some fairly violent surgery, but these were interestingly reexamined in John Harrison's 3-part miniseries, some fifteen years later.

Alec Newman made a far more plausible Paul than MacLachlan had. He looked streetwise and desert-hardened from the very beginning, and only Saskia Reeves seemed to have blundered in from some BBC kitchen sink drama by mistake. The fact that it was largely filmed in the Czech Republic also guaranteed some strikingly imaginative costume and set designs. All in all, it was a thoroughly creditable effort, which complemented rather than superseding Lynch's pioneering film.

Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune, dir. & writ. John Harrison (based on the novels Dune Messiah and Children of Dune by Frank Herbert)– with James McAvoy, Alec Newman, Alice Krige, Susan Sarandon – (USA, 2003)It was in the sequel that John Harrison's vision really started to pay off, though. The addition of Herbert's two sequels to the original Dune plotline helped greatly in fleshing out the true richness of the Dune universe. James McAvoy made a great Duke Leto, Paul Muad'Dib's son and heir - the future God Emperor of Dune of the fourth novel - and the complex intrigues and machinations surrounding the new Fremen imperium were spectacularly embodied on screen.

Alice Krige made a far better Lady Jessica than Saskia Reeves ever had, and most of the other casting decisions were similarly shrewd.

Dune: Part One, dir. Denis Villeneuve, writ. Denis Villeneuve, Jon Spaihts, & Eric Roth (based on the novel by Frank Herbert) – with Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson, Oscar Isaac, Josh Brolin, Stellan Skarsgård, Dave Bautista, Zendaya, Charlotte Rampling, Jason Momoa, Javier Bardem – (USA, 2021)All of which brings us, I guess, to the $64,000 question: what do you think of Denis Villeneuve's new film? I should begin by saying that for a Dune-ophile such as myself, any new movie based on Herbert's work is big news.

Having said that, I guess that I have to make a couple of provisos. First of all, I do find some of the adulation heaped on Villeneuve's sci-fi movies to date a bit misplaced. Arrival was, I thought, very good - mainly because of the ingenious plot of Ted Chiang's original short story.

I did my level best to like Blade Runner 2049, and - once again - found some points of interest in its approach to the tried-and-true android theme, but already a certain visual blankness seemed to be standing in for the seedy baroque magnificence of Ridley Scott's imagination.

Dune, too, looked frustratingly blank to me. The city of Arrakeen looked like an old concrete gun emplacement beefed up with a bit of CGI. The spaceships were larger and emptier than David Lynch's, but otherwise they lacked distinction - or any particular role beyond spectacle. Any cinema-goer these days has seen a few too many such space-scapes already.

What, then, of the performances? Some pretty impressive actors had been recruited to fill these oh-so-familiar roles, but they had - in almost every case - little to work with in the minimalist script. For all the richness of the plot material to get through in the first half of Herbert's book, this Dune (Part One) (as it's coyly labelled) seems to devote an inordinate amount of time to its characters' apparent desire to stare out to sea, or into space, or into the desert, without much to say.

It's not that I don't concede that internal monologues were somewhat overused as a device by Lynch, but that was a true reflection of Frank Herbert's own practice, and without them there's seldom enough in the dialogue to explain what's going on.

Who, then, stands out? Not, I'm afraid, Timothée Chalamet, who does a good enough job of playing the callow, young heir of a noble house, but shows few signs of his coming metamorphosis into Paul Muad'Dib, Messiah of Arrakis and Galactic Kwisatz Haderach. His puzzlement at the welcome he receives on arrival at the desert planet Arrrakis is, I fear, echoed by much of the cinema audience. There's just not a lot to him - at this point, at any rate.

Rebecca Ferguson as Jessica? Wonderful, I'm glad to say. It's true that I was already a bit of a fan, but she is, to me, the only actor on screen who seems actually to be there, on a strange, forbidding planet, caught in the toils of her Bene Gesserit sisterhood's plans.

Oscar Isaac - meh; Josh Brolin - God knows what movie he thought he was in; Stellan Skarsgård - a very disappointing Baron Harkonnen: a Halloween mask could have performed with more distinction; Dave Bautista - another massively talented comic actor, reduced to playing a thuggish sidekick; Zendaya - reduced mainly to wandering around in dream sequences; Chang Chen - when one thinks of what the late lamented Dean Stockwell made of his Doctor Yueh, this one seems pretty close to nothing; Sharon Duncan-Brewster - actually this seemed rather a nice notion: Max von Sydow (needless to say) was great in the role of Doctor Liet-Kynes, the imperial planetary ecologist, in the 1984 movie, but changing the character's gender and ethnicity made her far more believable, as well as the fact that she seemed more interested than most of the other in doing some actual acting; Charlotte Rampling - if you insist on hiding one of the best-known faces in cinema behind a rope net, little can be expected, and little was accordingly achieved: both of the previous cinematic Reverend Mothers were far superior; Jason Momoa - another interesting casting idea, but his obvious desire to be doing something all the time made him seem a bit out of step with the passivity of the production as a whole; and (last and unfortunately least) Javier Bardem - a dreadfully ill-judged casting decision; was he worse than the equally out-of-place Everett McGill's Stilgar in the original movie? He was certainly no better, that's for sure.

A lot of the problems here come down to a single factor. Denis Villeneuve seems entirely to lack a sense of humour. In the case of very intense, confined dramas, this can lead to highly effective results: in his early film Incendies (2010), for instance, or even his first Hollywood film Prisoners (2013).

But when the action portrayed is a bit over-the-top (which is a good description of Herbert's work in general), he seems to lack the tonal sense of how to shift registers, make it somehow less unbelievable with a well-timed joke or the adoption of a slightly less ponderous approach to things. Hence the strange trainwreck that was the film Sicario: a lot of nonsense about a very serious subject - a theme treated far more adroitly in Breaking Bad. Hence, too, the nasty and irrelevant psychopath subplot in his Blade Runner sequel: a tiresome intrusion on a film whose legitimate interests lay elsewhere.

To do the director credit, there's no character in Dune as irritating as Jared Leto in Blade Runner 2049, but Villeneuve still doesn't seem to understand that if you take out virtually all the background trimmings and subtleties from Frank Herbert's universe, you're left not with austerity but boredom. Cracking a joke or two, always David Lynch's first instinct to relieve the tension, seems to be quite off the agenda. There's not even any room in all these hours of cinema for a character so gleefully anarchic as Julie Cox's Princess Irulan in the John Harrison version.

Vague disappointment - that, I'm afraid, was the emotion I was left with. There was indeed much there on screen to enjoy (I particularly liked the dragonfly-like thopters).

As I said before, any Dune movie is cause for celebration among the faithful (the ones who intone "the Spice must flow" at regular intervals, and make a peculiar hand gesture at each appearance of the great sandworm, Shai-Hulud: "May His passage cleanse the world"). But Denis Villeneuve is no Ridley Scott, and there's little point in having such inflated expectations of him.

Naturally I'll be trotting off to see Part Two when it's released - if only to admire the Garbo-esque Rebecca Ferguson once again - and (who knows?) maybe this time Villeneuve'll pull out the stops a bit further. He's promised as much, after all.

But don't go dissing David Lynch in my presence anytime soon. A myth has grown up that his 1984 Dune movie was a disaster when it was, in fact, an eccentric masterpiece, one which gave fair warning of many transgressive cinematic excesses to come!

-

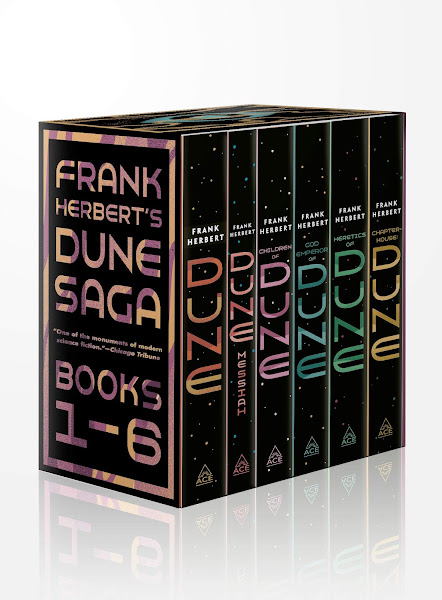

The Dune Series:

- Dune. [Part I, "Dune World": Analog (Dec 1963 – Feb 1964); Parts II and III, "The Prophet of Dune": Analog (Jan – May 1965)]. 1965. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1973.

- Dune Messiah. 1969. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1973.

- Children of Dune. 1976. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1977.

- God Emperor of Dune. 1981. London: New English Library, 1982.

- Heretics of Dune. 1984. London: New English Library, 1985.

- Chapter House Dune. 1985. London: New English Library, 1986.

- Destination: Void. 1966. Rev. ed. 1978. Penguin Science Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

- [with Bill Ransom]: The Jesus Incident. 1979. An Orbit Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1980.

- [with Bill Ransom]: The Lazarus Effect. 1983. An Orbit Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1984.

- [with Bill Ransom]: The Ascension Factor. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1988.

- Whipping Star. 1970. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1978.

- The Dosadi Experiment. 1977. A Futura Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1979.

- The Dragon in the Sea. 1956. [aka 'Under Pressure' and '21st Century Sub']. Penguin Science Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963.

- The Green Brain. 1966. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1979.

- The Eyes of Heisenberg. 1966. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1976.

- The Heaven Makers. 1968. London: New English Library, 1982.

- The Santaroga Barrier. New York: Berkeley, 1968.

- Soul Catcher. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1972.

- The Godmakers. ["You Take the High Road", Astounding (May 1958); "Missing Link", Astounding (Feb 1959); "Operation Haystack", Astounding (May 1959); "The Priests of Psi", Fantastic (Feb 1960)]. 1972. London: New English Library, 1984.

- Hellstrom's Hive. New York: Doubleday, 1973.

- Direct Descent. New York: Ace Books, 1980.

- The White Plague. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1982.

- [with Brian Herbert] Man of Two Worlds (with Brian Herbert), New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1986.

- High-Opp. WordFire Press, 2012.

- Angels' Fall. WordFire Press, 2013.

- A Game of Authors. WordFire Press, 2013.

- A Thorn in the Bush. WordFire Press, 2014.

- The Worlds of Frank Herbert. 1970. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1975.

- The Book of Frank Herbert. New York: DAW Books, 1973.

- The Best of Frank Herbert. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1975.

- The Priests of Psi. London: Gollancz Ltd, 1980.

- Eye. Illustrated by Jim Burns. 1985. New English Library. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1988.

- [with Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson]. The Road to Dune. Foreword by Bill Ransom. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., 2005.

- The Collected Stories of Frank Herbert. New York: Tor Books, 2014.

- Brian Herbert. Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. New York: Tor Books, 2003

The Pandora Sequence [aka the WorShip series]:

The ConSentiency Series:

Other Novels:

Short Story Collections:

Secondary: