The other day I bought a copy of Tim O'Brien's classic Vietnam war memoir from a Hospice Shop. It felt strange, very strange, to reread it - to revisit the atmosphere of those times. It was, after all, first published while the war was still going on, after the withdrawal of American troops, but before the ultimate humiliation of the fall of Saigon.

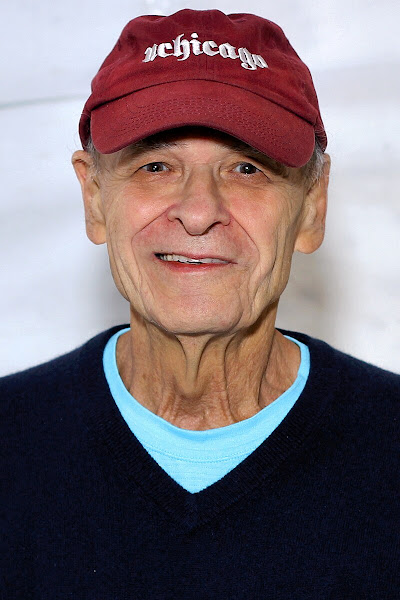

O'Brien is probably better known, now, for his National Book Award-winning Vietnam novel Going After Cacciato (1978), together with the linked stories in The Things They Carried (1990), but it's worth remembering that this memoir, whose original title was If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home was named the Outstanding Book of 1973 by the New York Times.

Why? I guess because O'Brien tried to cover all the bases: he was honest about his own internal debate about the "morality" of the war, but also admitted that it was largely by chance that he failed to run away to Sweden rather than being shipped off to Vietnam with his unit.

He turned out, again by chance, to be serving in the same region where the infamous My Lai massacre had taken place the year before. He records the casual killings and cruelty which were part of everyday life as an occupying force. But he also explains the constant fear of being killed or maimed by mines or mortar fire which gnawed away at most soldiers - apart from the occasional hero (or psychopath) - from day 1 to day 365 of their tours.

Mind you, if you want to draw any actual parallels between present day geopolitics and the fall of Saigon on on 30 April 1975, you'll have to look elsewhere. One place to go might be English poet and roving war correspondent James Fenton's classic All The Wrong Places: Adrift In The Politics Of Southeast Asia.

Fenton is still, perhaps, most famous - or notorious - for hitching a ride on a North Vietnamese tank just before it broke into the compound of the Saigon Presidential Palace. You can read some of his own thoughts on the matter in "The Fall of Saigon," from Granta 15 (1985).

And here are a few lines from one of his strangely Kiplingesque war poems, "Out of the East":

... it's a far cry from the temple yard

To the map of the general staff

From the grease pen to the gasping men

To the wind that blows the soul like chaff

And it's a far cry from the paddy track

To the palace of the king

And many go

Before they know

It's a far cry.

It's a war cry.

Cry for the war that has done this thing.

As usual, there are Academic histories a-plenty. Stanley Karnow's Vietnam: A History, billed in its later editions as "the first complete account of Vietnam at war," is the one that I dutifully read from cover to cover when I had to teach The Things They Carried in a Modern Novel course at Auckland Uni in the early 1990s.

I must admit, though, to a preference for the shorter and more focussed Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War, based on Michael Maclear's epic 1980 26-part Canadian TV documentary about the Vietnam War.

Even further back than that, when all these "old, unhappy far-off things" seemed considerably closer to us in time, I was asked to review an essay collection called Tell Me Lies About Vietnam: Cultural Battles for the Meaning of the War. Here's a quote from what I had to say about the subject then, in 1989:

... the fact that one has compiled and classified a series of responses to Vietnam in different media does not add up to a consistent view from which one can generalize. The war was appropriated by various interest groups ... but the infinite suffering and death that was inflicted on Indo-China by the Americans and their allies seems to me to be a fact which somewhat outweighs the importance, in the final analysis, of yet another spate of Narcissistic films and books about ‘the end of American innocence’. The virtues of this book lie in its particularity – its emphasis on individual artists (Ralph Steadman, Tim Page, Susan Sontag) and popular media (cartoons, comic books, rock music). Its errors reside in the assumption that some over-view of the falsification of the war can be deduced from all this – an attitude which is, in itself, as dangerous a ‘lie’ about Vietnam as any of those which the contributors expose.I might say it rather differently now - talk about over-complex, Grad School-inflected, run-on sentences! - but I still agree with that remark that "the infinite suffering and death ... inflicted on Indo-China by the Americans and their allies seems to me to be a fact which somewhat outweighs the importance ... of Narcissistic films and books about ‘the end of American innocence’." It's really just a question of proportion.

A 2008 study by the British Medical Journal came up with a ... toll of 3,812,000 dead in Vietnam between 1955 and 2002.The Wikipedia article from which I took these figures estimates 58,098 American casualties overall. Even if you dispute the BMJ's analysis - and some do - you still have a discrepancy of literally millions of military and civilian casualties inflicted in Vietnam by two foreign armies - the French and the Americans - neither of whom suffered even a tenth of this death toll themselves.

And yet, despite all that fire power and overwhelming military might - on paper - they still didn't win. The French were driven out by the Viet Minh, and a treaty of partition between North and South Vietnam was signed in Geneva on July 21, 1954. But the Americans insisted on reenacting the whole conflict on a larger scale, only to sign their own "Peace Accord" in Paris on January 27, 1973, officially ending their direct involvement in the Vietnam War.

A year later North Vietnamese forces toppled President Thieu's regime without any significant response from the U.S. The war had become too unpopular for anyone in power there to wish to resume it, and so the last pictures of what was then America's longest war were those disgraceful sauve-qui-peut scenes of America's friends and allies clamouring desperately for space on the last helicopters out.

It did take some time after that debacle for the old adage to be forgotten: "Never get into a land war in Asia". Just as it took Europe 25 years after 1914 to nerve itself up for another world war, so it took 25 years after 1975 before the Americans again decided to get into a quick war in Afghanistan to punish a few "fanatical extremists" - oddly enough, the same extremists (then referred to as the mujahideen) they'd been funding for decades, ever since the Soviet invasion in 1979.

Twenty years later, in 2021, the Americans withdrew in even more disgraceful circumstances than in 1975, having achieved far less, and leaving even larger crowds of those who had helped them at the mercy of the vengeful Taliban.

The parallels seem too obvious to be stressed, but maybe they still don't seem real to those who don't remember 1975, and may not have been born when the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan took place. Wars, however, are very real. They have a horrible way of coming home to you in unexpected ways: when a bomb goes off next to you for some obscure geopolitical reason, for instance.

I just wish we could show some signs of learning a few lessons from all this ancient history. For instance, that humiliating an entire country, not just their rulers - as Donald Trump has just done in Iran - is sowing the wind to reap the whirlwind. All empires crumble, and the fact that they tend to flex their muscles most ostentatiously just before their fall ought to remind the "great powers" that a return to the arts of peace and diplomacy is not necessarily a sign of weakness.

It's tempting, too, to remark that if the armies of the "free world" could learn to stop stomping around other people's backyards, their health services might end up having to deal with far fewer cases of PTSD. But the Forever War (as Noam Chomsky and others have called it) continues: sometimes it's Iraquis who are the enemy, sometimes Iranians, occasionally even Russians, but there's always got to be someone to machine-gun and bomb in the name of "liberal democracy".

-

Fiction:

- "Where Have You Gone, Charming Billy?" (1975)

- Northern Lights (1975)

- Northern Lights. 1975. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

- Going After Cacciato (1978)

- Going After Cacciato. 1978. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

- The Nuclear Age (1985)

- The Things They Carried (1990)

- The Things They Carried. 1990. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991.

- In the Lake of the Woods (1994)

- Tomcat in Love (1998)

- July, July (2002)

- America Fantastica (2023)

- If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home (1973)

- If I Die in a Combat Zone. 1973. Flamingo Modern Classics. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995.

- Dad's Maybe Book (2019)

- Greene, Graham. The Quiet American: Text and Criticism. 1955. Ed. John Clark Pratt. The Viking Critical Library. New York: Penguin, 1996.

- Herr, Michael. Dispatches. 1977. Introduction by David Leitch. Textplus. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989.

- Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. 1983. Rev. ed. London: Pimlico, 1990.

- Louvre, Alf & Jeffrey Walsh, ed. Tell Me Lies About Vietnam: Cultural Battles for the Meaning of the War. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1988.

- Maclear, Michael. Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War. 1981. London: Thames / Methuen, 1982.

- Sheehan, Neil. A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. 1988. London: Guild Publishing, by arrangement with Jonathan Cape, Ltd., 1989.

Non-fiction:

Secondary: