It was Wednesday the 6th of October, 2021. Auckland was in the middle of yet another COVID lockdown. We were feeling a bit peeved because (as usual) it seemed to be just us again: stuck in our bubbles, cycling through the same old bits of dross on TV, while the rest of the country went out to meet one another and enjoy the Spring weather.

But, as it turned out, we had not been forgotten! A care package arrived from my brother-in-law Greg and his partner Celia in Martinborough: two boxes of books from the Book Grocer.

I seized on the box of biographies, Bronwyn the box of craft books. Besides a couple of celebrity pop star memoirs, which didn't really take my fancy, my box contained:

- Frederick Forsyth: The Outsider: My Life in Intrigue (2015)

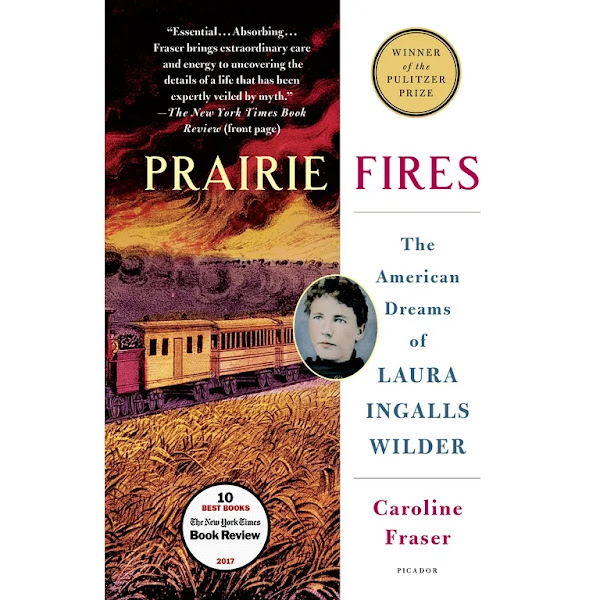

- Caroline Fraser: Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)

- Nelson Mandela: Dare Not Linger: The Presidential Years (2016)

- Philip Norman: Paul McCartney: The Life (2016)

- Ramie Targoff: Renaissance Woman: The Life of Vittoria Colonna (2018)

- Frances Wilson: Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (2016)

It's probably only right that I should confess that the first book that fell open in my hand was the biography of Paul McCartney, Since then I've gone even further down that particular rabbit hole by purchasing Irish poet Paul Muldoon's weirdly compelling edition of the former's collected lyrics:

Getting back to the point, though, I was especially excited to see there a copy of Caroline Fraser's Pulitzer-Prize-winning biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, an author whom I read a good deal of as a child once I managed to get over my prejudice against such a "girly-looking" set of books.

My mother and sister were particular devotees of her work; all of us watched the saccharine, Michael Landon-dominated Little House on the Prairie TV series with gritted teeth, amid repeated asseverations that the books were "not like that."

Blanche Hanalis: Little House on the Prairie (1974-83)

Blanche Hanalis: Little House on the Prairie (1974-83)l-to-r: Michael Landon as 'Charles Ingalls', Melissa Sue Anderson as 'Mary', Karen Grassle as 'Caroline',

Rachel Lindsay Greenbush as 'Carrie', & Melissa Gilbert as 'Laura'

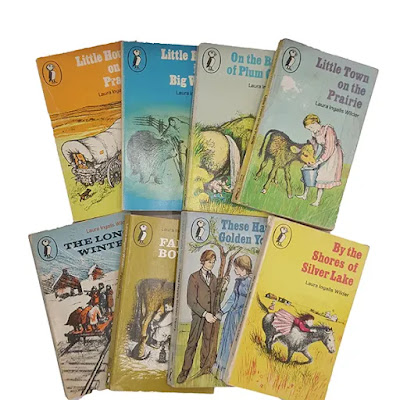

Here they all are, in the 1970s Puffin copies we read, with the charming pencil and charcoal illustrations commissioned from American artist Garth Williams for a uniform edition in the late 1940s / early 1950s:

- Little House in the Big Woods (1932)

- Farmer Boy (1933)

- Little House on the Prairie (1935)

- On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937)

- By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)

- The Long Winter (1940)

- Little Town on the Prairie (1941)

- These Happy Golden Years (1943)

The picture directly above, from Roslyn Jolly's own book-related blog, comes from a post written during the 2020 COVID lockdown in Australia. She, too, saw certain parallels between the privations described in Wilder's books and the strange new lifestyle imposed on us by the virus mandates:

The Long Winter must have made a great impression on me, because I found myself thinking of it almost as we started to find the shape of our days under the new COVID-19 restrictions. No travel. No leaving the house except for essential purposes. No meetings with anyone outside the household. The restlessness of being cooped up. Tensions flaring within the family. A growing sense of isolation from the rest of society. I’d encountered it all before, in Wilder’s book.That does seem to be a common theme when these books are discussed - not so much the moral lessons inculcated by them, as their direct appeals to shared experience. The Long Winter is probably my favourite among them, too. It's so much more condensed and single-minded than the others - and the settlers' failure to heed the old Indian's warning at the beginning gives a satisfying sense of poetic justice to the whole story.

Laura Ingalls Wilder scholarship, too, is certainly the province of some very engaged and single-minded enthusiasts. Before Caroline Fraser's biography was published in 2017, the main sources of information about the author were the biographies by William Anderson - who also edited Wilder's Selected Letters (2017) - and Pamela Smith Hill.

Despite the fact that Hill also edited the 2014 annotated edition of Laura Ingalls Wilder's original 1930 autobiography, Pioneer Girl, I was surprised to find virtually no reference to her in Fraser's work. She isn't mentioned in the index, and - since Fraser's book has notes but no bibliography - it's a little difficult even to locate the details of the annotated Pioneer Girl there, either.

Am I wrong to suspect some friction between the two? It certainly looks a bit like that. Fraser - one of whose previous books was entitled Rewilding the World - has solid credentials in the environmental movement. Hill, by contrast, is a children's writer and creative writing teacher with more pronounced roots in the American MidWest.

I guess it came as a surprise to many when Laura Ingalls Wilder achieved canonisation in the Library of America series in 2012, the first purely children's writer to do so - though she's since been joined there by Madeleine L'Engle and Virginia Hamilton. The editor of their two 'Little House' volumes was Caroline Fraser:

Hill's version of Pioneer Girl came out two years after this. So far as I can tell, it makes no reference to the Library of America edition: either by citing its (very useful) chronology or its bibliographical details. Hill's latest word on the subject is, however, due to appear from the University of Nebraska Press in a couple of months time:

Curiously enough, Caroline Fraser - but not Pamela Smith Hill - was asked to contribute to a 2017 symposium of essays on Wilder which appeared under the same auspices as the annotated Pioneer Girl.

And, lest that be seen as an accidental omission, it's perhaps equally significant that the editors of the "Pioneer Girl project" have gone on to supplement Pamela Smith Hill's syncretic text of Wilder's original scribbled pencil manuscript with new editions of the all the various overlapping versions of her autobiography.

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed: Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts (2022)

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed: Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts (2022) Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed: Pioneer Girl: The Path into Fiction (2023)

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed: Pioneer Girl: The Path into Fiction (2023)Mind you, I could easily be seeing friction where there's actually mutual respect - either that, or complete indifference. I somehow doubt it, though. The world of scholarship is not exactly replete with constructive, happy rivalries. Caroline Fraser's mainstream triumphs - the Library of America, the Pulitzer Prize - have ended up putting Pamela Smith Hill rather in the shade, whether intentionally or not.

The real winners, though, are undoubtedly readers such as myself. I certainly found the annotated Pioneer Girl a wonderfully immersive book. As Marthe Bijman remarks in her review of it on the Seven Circumstances site:

The text of Wilder’s original Pioneer Girl memoir is reproduced in the book, and contrasted and highlighted with copious, and I do mean copious, annotations, references and explanations.

It is hard to fault in that regard. The maps are clear and well-placed, and the pictures - such as the Helen Sewell illustration above - judiciously chosen for maximum impact. As something of a connoisseur of annotated editions, I'd have to rate this one in the top ten percent for both entertainment and information. It's perhaps a little large for casual reading, but then that is the norm for such books.

Bijman stresses that, while "Pioneer Girl is much more complicated and personal than the books":

This is the definitive guide to Laura Ingalls Wilder and her life from to 1869 in Kansas to 1888 in Dakota Territory. Almost every word in the memoir has been annotated and the references are detailed, with documents, photos, registers and archival materials. Yes, the Little House books have lost some of their charm because I now understand they are more fiction than autobiographical – but there is still magic in the books.

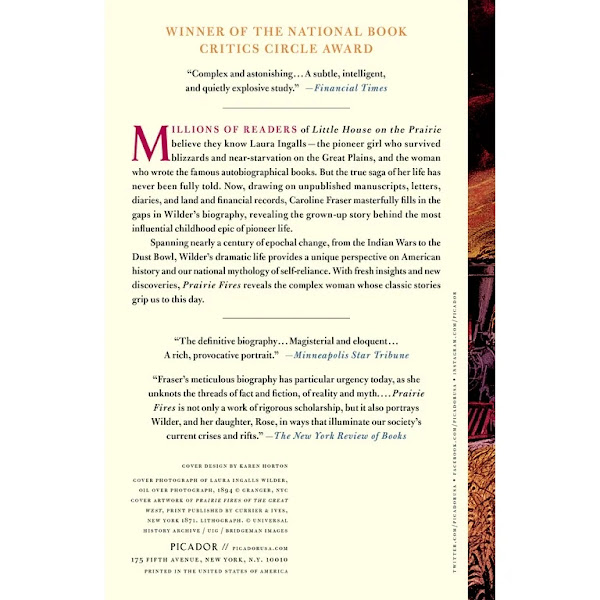

As for Caroline Fraser's work, the chorus of praise it's attracted really speaks for itself. It should be stressed, however, that this is a warts-and-all biography which omits none of the unfortunate contradictions between the reality of Laura Ingalls Wilder's life and the neat resolutions imposed on it by her autobiographical fictions.

It's not so much a simple life-and-times, as an expert weaving of American history in all its variety and violence into an account of the crippling hardships suffered by the Ingalls family and their neighbours during the late, post-Civil War period of Westward Expansion.

From the Dakota war of 1862, with its barbarous aftermath of mass executions and enforced displacement of the Sioux people; through the homesteading era, with its droughts and locust infestations; all the way to the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, Fraser points out the hidden significances behind Wilder's apparently ingenuous and factual books.

In particular, she traces the vexed relationship between Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter Rose Wilder Lane, herself a celebrated writer in the 1920s and 30s - though she's now better known as one of the ideologues (along with Ayn Rand) behind the American libertarian movement.

Lane was both her mother's Maxwell Perkins, the editorial presence who inspired and helped to shape her books, and her nemesis: a conscienceless spirit of misrule, who alternately longed for and repudiated her family but could never really separate herself from them.

All in all, it's a rattling good yarn - every bit as good as any of Wilder's own. It's hard to imagine any serious study or appreciation of the Little House books being possible in the future without a thorough grounding in Caroline Fraser's insights. But it's also easy to see how much it must have offended some of Wilder's more conservative admirers when it first came out.

Given that Fraser's previous books include God's Perfect Child (1999), an account of her upbringing in the Christian Science Church - described as follows in a New York Times review by Philip Zaleski: "Few darker portraits of [Mary Baker Eddy] have emerged since the days when Mark Twain called her a brass god with clay legs" - her status as a tearer-down of false gods is undeniable.

That great sceptic and authority on the lunatic fringe, Martin Gardner, said of her:

No one has written more entertainingly and accurately than Fraser about the history of Christian Science ... No one has more colorfully covered the ... endless bitter schisms and bad judgments that have dogged it ...Anita Sethi, in her turn, has praised Prairie Fires for demonstrating that "Memories can be both 'treasures' and 'consuming fires of torment':

Caroline Fraser’s rigorously researched biography shows how [Laura Ingalls Wilder]’s life was so much more painful than it appears in her autobiographical writings ... At its best, the book displays both the perils and the power of memory.

In the dark days we're living through at present, with a USA which has revived its delusions of Manifest Destiny in a globalised world no longer equipped to co-exist with them, the parable of Laura Ingalls Wilder's actual life, and self-created legend, seems to have particular significance.

American exceptionalism; American lives; American this, that and the other ... the unfortunate elision of this adjective with the word "human" is something we've had to put up with for many years now. But whether any of us like it or not, I doubt that this collective mirage can survive for much longer.

Americans are notorious for being both their own bitterest critics and their own windiest boosters. It's nice to take confirmation from Caroline Fraser's excellent, hard-hitting book, that the defenders of the former tradition are alive and well and ready to do battle for the meaning of their history - which may, ominously, turn out to be the shape of their own future.

-

The Little House books:

- Little House in the Big Woods. Illustrated by Helen Sewell (1932)

- Little House in the Big Woods. 1932. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1963. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Farmer Boy. Illustrated by Helen Sewell (1933)

- Farmer Boy. 1933. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1972. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

- Little House on the Prairie. Illustrated by Helen Sewell (1935)

- Little House on the Prairie. 1935. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1964. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- On the Banks of Plum Creek. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1937)

- On the Banks of Plum Creek. 1937. Rev. ed. 1953. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1965. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

- By the Shores of Silver Lake. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1939)

- By the Shores of Silver Lake. 1939. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1967. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

- The Long Winter. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1940)

- The Long Winter. 1940. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980.

- Little Town on the Prairie. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1941)

- Little Town on the Prairie. 1941. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1969. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- These Happy Golden Years. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1943)

- These Happy Golden Years. 1943. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

- The Little House Books, Vol. 1. Ed. Caroline Fraser. Library of America, 229 (2012)

- Little House in the Big Woods (1932)

- Farmer Boy (1933)

- Little House on the Prairie (1935)

- On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937)

- The Little House Books, Volume One. Ed. Caroline Fraser. 2 vols. The Library of America, 229. [‘Little House in the Big Woods,’ 1932; ‘Farmer Boy,’ 1933;‘Little House on the Prairie,’ 1935; ‘On the Banks of Plum Creek,’ 1937]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2012.

- The Little House Books, Vol. 2. Ed. Caroline Fraser. Library of America, 230 (2012)

- By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)

- The Long Winter (1940)

- Little Town on the Prairie (1941)

- These Happy Golden Years (1943)

- The First Four Years (1971)

- The Little House Books, Volume Two. Ed. Caroline Fraser. 2 vols. The Library of America, 230. [‘By the Shores of Silver Lake,’ 1939; ‘The Long Winter,’ 1940; ‘Little Town on the Prairie,’ 1941; ‘These Happy Golden Years,’ 1943; ‘The First Four Years,’ 1971]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2012.

- On the Way Home: The Diary Of A Trip From South Dakota To Mansfield, Missouri in 1894. Ed. Rose Wilder Lane (1962)

- The First Four Years (1971)

- The First Four Years. 1971. Epilogue by Rose Wilder Lane from "On the Way Home". 1962. 1973. Puffin Books. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

- West From Home: Letters Of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco, 1915. Ed. Roger Lea MacBride (1974)

- A Little House Sampler. With Rose Wilder Lane. Ed. William Anderson (1988 / 1989)

- Little House in the Ozarks: The Rediscovered Writings. Ed. Stephen W. Hines (1991)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder & Rose Wilder Lane, Letters 1937–1939. Ed. Timothy Walch (1992)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Farm Journalist: Writings from the Ozarks. Ed. Stephen W. Hines (1997)

- A Little House Reader: A Collection of Writings. Ed. William Anderson (1998)

- Laura's Album: A Remembrance Scrapbook of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Ed. William Anderson (1998)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder's Fairy Poems. Ed. Stephen W. Hines. Illustrated by Richard Hull (1998)

- A Little House Traveler: Writings from Laura Ingalls Wilder's Journeys Across America (2006)

- On the Way Home (1894)

- West from Home (1915)

- The Road Back Home (1931)

- Writings to Young Women. Ed. Stephen W. Hines (2006)

- On Wisdom and Virtues

- On Life as a Pioneer Woman

- As Told by Her Family, Friends, and Neighbors

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1911–1916: The Small Farm. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1917–1918: The War Years. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1919–1920: The Farm Home. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1921–1924: A Farm Woman. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder's Most Inspiring Writings: Covering the Years 1911 Through 1924. Ed. Dan L. White (2015)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Pioneer Girl's World View: Selected Newspaper Columns (2014)

- Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography. Ed. Pamela Smith Hill (2014)

- Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography. Ed. Pamela Smith Hill. A Publication of the Pioneer Girl Project: Nancy Tystad Koupal, Director; Rodger Hartley, Associate Editor; Jeanne Kilen Ode, Associate Editor. Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2014.

- The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Pioneer's Correspondence. Ed. William Anderson (2017)

- Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts. Ed. Nancy Tystad Koupal (2022)

- Pioneer Girl: The Path into Fiction. Ed. Nancy Tystad Koupal (2022)

- Zochert, Donald. Laura: The Life of Laura Ingalls Wilder (1976)

- Anderson, William. Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography (1992)

- Holtz, William. The Ghost in the Little House: A Life of Rose Wilder Lane (1993)

- Miller, John E. Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend (1998)

- Hill, Pamela Smith. Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer's Life (2007)

- Miller, John E. Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture (2008)

- Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder. Ed. Nancy Tystad Koupal (2017)

- Fraser, Caroline. Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Metropolitan Book. New York: Henry Holt And Company, 2017.

- Hill, Pamela Smith. Too Good to Be Altogether Lost: Rediscovering Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House Books (2025)

Published posthumously:

Secondary:

•