So who, so far, has played Winston Churchill on screen? Just about every portly British actor of a certain age, that's who. Nicholas Asbury, Brian Cox, Albert Finney, Michael Gambon, Robert Hardy, Bob Hoskins, Toby Jones, John Lithgow, Ian McNeice, Gary Oldman, Timothy Spall, Simon Ward, Timothy West - even American comic John Lithgow. Do any of them look at all like the man himself? No, not particularly. But on they come, scowling and spitting, nevertheless.

They've certainly come at the problem of how to represent him from virtually every angle, one must admit: as a schoolboy and young adventurer in Young Winston; as a WWI Cabinet Minister in 37 Days; as a prophetic outcast in The Wilderness Years and The Gathering Storm; as wartime PM in Into the Storm, Churchill and the Generals, and now Churchill and the yet-to-be-released Darkest Hour; and then as a dithering old monument of the Tory party in Churchill's Secret and The Crown. Apparently, according to the IMDb, there have been no fewer than 208 such screen impersonations so far.

Why do I keep on watching them? Am I insane? (Don't answer that). It's not that there's much to be expected from each new growl-athon, and yet I find myself drawn to them for some odd reason. It's certainly not that I approve of his Conservative, Empire-building politics - and as for that statement at the end of Churchill, one of the very worst of these films, that he is 'often acclaimed as the greatest Briton of all time,' what does that even mean? Was he a better writer than Shakespeare? A more important statesman than Cromwell? A more visionary strategist than his great ancestor the Duke of Marlborough? Clearly not.

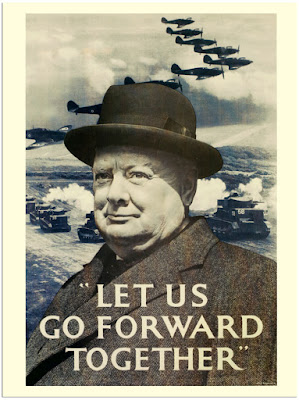

And yet ... It's impossible for someone of my generation, at least, to listen to those 1940s speeches of Churchill's - even soundbytes from same - without emotion. Just those little phrases: "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat" - "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few" - and, above all, "Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, This was their finest hour."

You ask, what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark and lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory. Victory at all costs — Victory in spite of all terror — Victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory there is no survival.

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God's good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.That's the true Churchillian music. That was the moment when a lifetime of poring over maps and old books, and practising his orotund oratorical skills in parliament and on the hustings paid off, and the world suddenly stopped, and listened, and liked what they heard.

What they heard was defiance, and that was what was needed then - but there was more to it than that. It was how he put it. It was the difference between the vicious ravings of Dr. Goebbels - Wollt ihr den totalen Krieg? - and the warlike speeches in Henry V. It mattered, somehow.

Maybe that's why I keep on coming back to these films. After watching the deplorable spectacle a couple of days ago of President Trump introducing his cabinet of dullards and losers, each one of whom said what an "honour" and a "privilege" it was to serve their pitiful Dark Lord - shades of the compulsory standing ovations after each of Stalin's speeches ("Never be the first to stop clapping, Comrade") - it's refreshing to hear someone expressing such honest defiance against all the shopsoiled tyrants of the world ...

So here's my own list. I've seen all but one or two of them, I think. And I fear I'll be trotting along dutifully to watch Gary Oldman add his bit of cigar-puffing and wheezing to all the others in a few months time:

- Young Winston: feature film, dir. Richard Attenborough, writ. Carl Foreman (based on Churchill's memoir My Early Life) - with Simon Ward as Churchill & Anne Bancroft as his Mum, Lady Randolph Churchill (née Jennie Jerome) - (UK, 1972)

- Churchill and the Generals: made-for-TV film, dir. Alan Gibson, writ. Ian Curteis - with Timothy West as Churchill - (UK, 1979)

- Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years: 8-part TV Series, dir. Ferdinand Fairfax, writ. Ferdinand Fairfax & William Humble (based on Martin Gilbert's biography) - with Robert Hardy as Churchill & Siân Phillips as Clementine Churchill ('Clemmie') - (UK, 1981)

- World War II: When Lions Roared: 3-part TV miniseries, dir. Joseph Sargent, writ. David Rintels - with Bob Hoskins as Churchill, John Lithgow as Roosevelt & Michael Caine as Stalin - (USA, 1994)

- The Gathering Storm: feature film, dir. Richard Loncraine, writ. Hugh Whitemore - with Albert Finney as Churchill & Vanessa Redgrave as 'Clemmie' - (UK / USA, 2002)

- Into the Storm [aka Churchill at War]: feature film, dir. Thaddeus O'Sullivan, writ. Hugh Whitemore - with Brendan Gleeson as Churchill & Janet McTeer as Clemmie - (UK / USA, 2009)

- The King's Speech: feature film, dir. Tom Hooper, writ. David Seidler - with Timothy Spall as Churchill - (UK, 2010)

- Dr Who: Victory of the Daleks: TV series, dir. Andrew Gunn, writ. Mark Gatiss - with Ian McNeice as Churchill - (UK, 2010)

- Fleming: The Man Who Would be Bond: 4-part TV miniseries, dir. Mat Whitecross, writ. John Brownlow & Don Macpherson - with Toby Jones as Churchill - (UK, 2014)

- 37 Days: 3-part TV miniseries, dir. Justin Hardy, writ. Mark Hayhurst - with Nicholas Asbury as Churchill - (UK, 2014)

- Churchill's Secret: made-for-TV film, dir. Charles Sturridge, writ. Stewart Harcourt (based on the book The Churchill Secret: KBO by Jonathan Smith) - with Michael Gambon as Churchill & Lindsay Duncan as Clemmie - (UK / USA, 2016)

- The Crown: Series 1: 10-part TV Series, writ. Peter Morgan - with John Lithgow as Churchill - (UK / USA, 2016)

- Churchill: feature film, dir. Jonathan Teplitzky, writ. Alex von Tunzelmann - with Brian Cox as Churchill & Miranda Richardson as Clemmie - (UK, 2017)

- Darkest Hour: feature film, dir. Joe Wright, writ. Anthony McCarten - with Gary Oldman as Churchill & Kristin Scott Thomas as Clemmie - (UK, 2017)

Great stuff. Hugely entertaining. It also had the effect of putting me onto My Early Life, which is probably Churchill's most entertaining book.

Haven't seen it. It sounds pretty good, though. I presume it's based - at least partially - on Field Marshall Alanbrooke's very revealing diaries about his time with Churchill.

Love it. A lot of detail, and a genuine sense of the complexity of his personality. Siân Phillips plays a sinuous and rather distant Clemmie (a lot like her Livia in I Claudius, actually).

Haven't seen it. The prospect of seeing Michael Caine, of all people, play Stalin makes it tempting to hunt it down, though. It's funny to think of John Lithgow going full circle from Roosevelt, here, to Churchill in The Crown - with a quarter of a century in between.

Rather repetitive of The Wilderness Years, but still very dramatic and entertaining. Vanessa Redgrave is a rather more affectionate but distinctly more tempestuous Clemmie than Siân Phillips.

A shame they couldn't keep the same cast as in The Gathering Storm, but still a good overview of the war years, focussing on 1940 as a flashback from election defeat in 1945. Brendan Gleeson is a lot less loveable and definitely more of a pain than Albert Finney, but Janet McTeer's Clemmie steers a steady course between the Scylla of Siân and the Charybdis of Vanessa.

I guess it was inevitable that he'd get to do it sooner or later: somewhere between his bestial Turner and his suave and manipulative David Irving comes Timothy Spall's Churchill.

Not a subtle impersonation, perhaps, but then the modern version of Dr Who doesn't really do subtle.

Just a cameo, really, but rather a good show on Toby Jones's part, I thought - making a nice change from the tedious bedhopping of the protagonist and the future Mrs. Fleming.

Churchill is played here as a knowing politician, alert to all the complexities of a question which apparently evade his superiors. Whether - to one, like myself, who's read his 5-volume World War I memoirs The World Crisis - this is accurate or not is questionable, but it makes for good drama, at any rate.

Kind of a pointless piece of mystification. Churchill's advisors cover up how unfit he is for office, all of which plays some part in making Anthony Eden so frustrated that he takes it out on Nasser. True(ish), possibly, but not exactly earth-shattering.

This I haven't yet seen, but I'm rather looking forward to doing so.

While I have to confess to enjoying it overall, I do think the multiple inaccuracies and exaggerations of the film do make it a very unfortunate version of Churchill. Certainly he was a pain around the office. Certainly he opposed the frontal assault in France (proposing, according to Alanbrooke, a diversion to Portugal at a very late stage in proceedings). Certainly he demanded to go over himself on D-Day - but all the Gallipoli references completely belie his own view of that campaign. Of course it was a disaster, but his point (as expounded very thoroughly in volume 2 of The World Crisis) was that this was inevitable given the piecemeal and futile way the idea of a landing was stumbled into. To give it as the main reason why he opposed the Normandy landings is sentimental tosh and plain wrong: and putting in all those stupid details designed to show how "out-of-date" he was in terms of contemporary tactics is also very misleading. Nor is the choice of Montgomery as the visionary commander putting him straight a particularly happy one, given the latter's blunders in Normandy and after ... Still, there are some pretty moments here and there. Miranda Richardson plays by far the most terrifying and contemptuous Clemmie to date.

I presume - though I don't know - that this will be about the period when Churchill was fighting Lord Halifax in cabinet to prevent the initiation of peace-talks (brokered by Mussolini) after the fall of France. Subsequent historians have suggested that this was a more vicious and no-holds-barred battle than anything that followed it in parliament, let alone the country at large. Hitler still had many friends and admirers in the British establishment at that point, and they would have done virtually anything to prevent a shooting war. That's the context where those speeches, quoted above, come in. Is it better to die on your feet than live on your knees? That's not, and never has been, an easy question to answer.

•

And here's a list of my own Churchilliana. I do find his books very readable and well expressed (if a trifle tendentious at times), and certainly indispensable to any student of the great European Civil War (1914-45). Some, though, are genuinely illuminating. Having read both G. M. Trevelyan's classic England Under Queen Anne trilogy (1930-34) and Churchill's four-volume Marlborough biography in very close succession last year, I can tell you that the latter certainly complements the former very well, and (almost) made it possible for me to understand the morass of late seventeenth / early eighteenth century European politics for the first time.

Books I own are marked in bold:

- The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898)

- The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War. 1898. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1901.

- The River War. Ed. Colonel Francis Rhodes. 2 vols (1899)

- The River War. 1899. A Four Square Book. London: New English Library, 1964.

- London to Ladysmith via Pretoria (1900)

- Ian Hamilton's March (1900)

- Frontiers and Wars: His Four Early Books, Covering His Life as Soldier and War Correspondent, Edited into One Volume. ["The Story of the Malakand Field Force" (1898); "The River War" (1899); "London to Ladysmith via Pretoria" (1900); "Ian Hamilton's March" (1900)]. 1962. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

- Lord Randolph Churchill. 2 vols (1906)

- Lord Randolph Churchill. 2 vols. London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1906.

- My African Journey (1908)

- My African Journey. 1908. London: Icon Books Limited, 1964.

- The World Crisis. 6 vols (1923–1931)

- 1911–1914 (1923)

- 1915 (1923)

- 1916–1918 (Part 1) (1927)

- 1916–1918 (Part 2) (1927)

- The Aftermath (1929)

- The Eastern Front (1931)

- The World Crisis. Introduction by Martin Gilbert. 2005. London: The Folio Society, 2007.

- Volume 1: 1911-1914 (1923)

- Volume 2: 1915 (1923)

- Volume 3: 1916-1918 (1927)

- Volume 4: The Aftermath (1929)

- Volume 5: The Eastern Front (1931)

- The World Crisis: 1911-1918. 1923, 1927. Rev. ed. 1931. A Four Square Book. London: Landsborough Publications Limited, 1960.

- My Early Life [US: 'A Roving Commission: My Early Life'] (1930)

- My Early Life: A Roving Commission. 1930. The Fontana Library. London: Collins, 1959.

- Thoughts and Adventures [US: 'Amid These Storms'] (1932)

- Thoughts and Adventures. 1932. London: Thomas Butterworth, Ltd., 1933.

- Marlborough: His Life and Times. 4 vols (1933–1938)

- Marlborough: His Life and Times. 2 vols. 1947. London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd., 1966 & 1969.

- Book One: Consisting of Volumes I and II of the Original Work (1933 & 1934)

- Book Two: Consisting of Volumes III and IV of the Original Work (1936 & 1938)

- Marlborough: His Life and Times. 1933, 1934, 1936, 1938. 4 vols. London: Sphere Books, 1967.

- Marlborough: His Life and Times. 2 vols. 1947. London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd., 1966 & 1969.

- Great Contemporaries (1937)

- Great Contemporaries. 1937. The Fontana Library. London: Collins, 1965.

- The Second World War. 6 vols (1948–1953)

- The Gathering Storm (1948)

- Their Finest Hour (1949)

- The Grand Alliance (1950)

- The Hinge of Fate (1950)

- Closing the Ring (1951)

- Triumph and Tragedy (1953)

- The Second World War. 6 vols. London: Cassell & Co., Ltd., 1948-54.

- Volume 1: The Gathering Storm (1948)

- Volume 2: Their Finest Hour. 1949. 5th Edition (1955)

- Volume 3: The Grand Alliance (1950)

- Volume 4: The Hinge of Fate. 1951. 2nd Edition (1951)

- Volume 5: Closing the Ring (1952)

- Volume 6: Triumph and Tragedy. 1954. 2nd edition (1954)

- The Second World War. And an Epilogue on the Years 1945 to 1957: Abridged One-Volume Edition. 1948-1954. Ed. Dennis Kelly. London: Cassell, 1959.

- A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (1956–1958)

- The Birth of Britain (1956)

- The New World (1956)

- The Age of Revolution (1957)

- The Great Democracies (1958)

- A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. 4 vols. 1956-58. London: Cassell & Co., Ltd., 1971-72.

- Volume 1: The Birth of Britain. 1956 (1972)

- Volume 2: The New World. 1956 (1971)

- Volume 3: The Age of Revolution. 1957 (1971)

- Volume 4: The Great Democracies. 1958 (1971)

- Young Winston's Wars: The Original Dispatches of Winston S. Churchill, War Correspondent, 1897–1900 (1972)

- Young Winston’s Wars: The Original Despatches of Winston S. Churchill, War Correspondent 1897-1900. Ed. Frederick Woods. London: Sphere Books, 1972.

- The Collected Essays. 4 vols (1976)

- Memories and Adventures (1989)

- "Man Overboard; an Episode of the Red Sea." The Harmsworth Magazine (1898)

- Savrola (1900)

- Savrola: a Tale of the Revolution in Laurania. 1900. London: Beacon Books, 1957.

- "If Lee Had NOT Won the Battle of Gettysburg". In If It Had Happened Otherwise. Ed. J. C. Squire (1931)

- "The Dream". 1947. The Sunday Telegraph (1966)

- Mr Broderick's Army 1903)

- For Free Trade 1906)

- Liberalism and the Social Problem 1909)

- The People's Rights 1910)

- Parliamentary Government and the Economic Problem 1930)

- India: Speeches and an Introduction 1931)

- Arms and the Covenant [US: "While England Slept"]. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1938)

- Step by Step: 1936–1939. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1939)

- Addresses Delivered (1940)

- Into Battle [US: "Blood, Sweat and Tears"]. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1941)

- Broadcast Addresses (1941)

- The Unrelenting Struggle. Ed. Charles Eade (1942)

- The End of the Beginning. Ed. Charles Eade (1943)

- Winston Churchill, Prime Minister (1943)

- Onwards to Victory. Ed. Charles Eade (1944)

- The Dawn of Liberation. Ed. Charles Eade (1945)

- Victory. Ed. Charles Eade (1946)

- Secret Sessions Speeches [US: "Winston Churchill's Secret Sessions Speeches"]. Ed. Charles Eade (1946)

- War Speeches. Ed. F. B. Czarnomskí (1946)

- World Spotlight Turns on Westminster (1946)

- The Sinews of Peace. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1948)

- Europe Unite: Speeches 1947 and 1948. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1950)

- In the Balance: Speeches 1949 and 1950. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1951)

- The War Speeches. Ed. Charles Eade (1952)

- King George VI: The Prime Minister's Broadcast, February 7, 1952 (1952)

- Stemming the Tide: Speeches 1951 and 1952. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1953)

- The Unwritten Alliance: Speeches 1953 and 1959. Ed. Randolph Churchill (1961)

- Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897-1963. 8 vols. Ed. Robert Rhodes James (1974)

- Charles, IXth Duke of Marlborough, KG: Tributes by Rt. Hon. W. Spencer-Churchill and C. C. Martindale (1934)

- Painting as a Pastime (1948)

- Painting as a Pastime. 1932 & 1948. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965.

- Maxims and Reflections [Rev. ed.: "Sir Winston Churchill: A Self-Portrait", 1954] (1948)

- [Ed., with others] The Eagle Book of Adventure Stories (1950)

- The Wisdom of Sir Winston Churchill (1956)

- Winston Churchill's Anti-Depression Proposal to Halt Inflation, Stabilize Prosperity, and Insure Full Freedom (1958)

- Churchill: His Paintings. Compiled by David Coombs and Minnie Churchill (1967)

- The Roar of the Lion (1969)

- Joan of Arc (1969 )

- Winston Churchill on America and Britain: A Selection of His Thoughts on America and Britain. Foreword by Lady Churchill (1970)

- [with John Glubb] Great Issues 71: A Forum on Important Questions Facing the American Public (1972)

- If I Lived My Life Again. Ed. Jack Fishman (1974)

- The Collected Poems of Sir Winston Churchill. Ed. F. John Herbert (1981)

- Churchill and Roosevelt: The Complete Correspondence. Ed. Warren F. Kimball (1984)

- Winston Churchill and Emery Reves: Correspondence, 1937–1964 (1997)

- Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill. Ed. Mary Soames (1998)

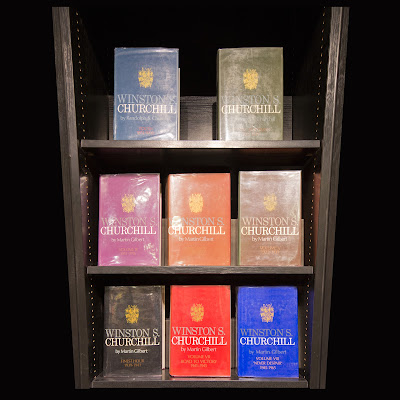

- Churchill, Randolph. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 1: Youth, 1874-1900. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1966.

- Churchill, Randolph. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 2: Young Statesman, 1901-1914. 8

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 3: The Challenge of War, 1914-1916. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1971.

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 4: The Stricken World, 1916-1922. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1975.

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 5: Prophet of Truth, 1922-1939. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1976.

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 6: Finest Hour, 1939-1941. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1983.

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 7: Road to Victory, 1941-1945. 8 vols. William Heinemann Ltd. London: Book Club Associates, 1986.

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 8: Never Despair, 1945-1965. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1988.

- Gilbert, Martin. Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years. London: Macmillan London Limited, 1981.

Non-Fiction:

Fiction:

Collected Speeches:

Miscellaneous:

Letters:

Secondary:

•