June 17, 1905

Dear Mr. Johnson:

Just back from three months in Europe, I find your letter of May 16th awaiting me, with the very flattering news of my election into the Academy of Arts and Letters. I own that this reply gives me terrible searchings of the heart.

On the one hand the lust of distinction and the craving to be yoked in one Social body with so many illustrious names tempt me to say “yes.” On the other, bidding me say “no,” there is my life‐long practice of not letting my name figure where there is not some definite work doing in which I am willing to bear a share; and there is my life‐long professional habit of preaching against the world and its vanities.

I am not informed that this Academy has any very definite work cut out for it of the sort in which I could bear a useful part; and it suggests tant soit peu the notion of an organization for the mere purpose of distinguishing certain individuals (with their own connivance) and enabling them to say to the world at large “we are in and you are out.”

Ought a preacher against vanities to succumb to such a lure at the very first call? Ought he not rather to “refrain, renounce, abstain,” even tho it seem a sour and ungenial act? On the whole it seems to me that for a philosopher with my pretensions to austerity and righteousness, the only consistent course is to give up this particular vanity, and treat myself as unworthy of the honour, which I assuredly am. And I am the more encouraged to this course by the fact that my younger and shallower and vainer brother is already in the Academy, and that if I were there too, the other families represented might think the James influence too rank and strong.

Let me go, then, I pray you, “release me and restore me to the ground.” If you knew how greatly against the grain these duty‐inspired lines are written, you would not deem me unfriendly or ungenial, but only a little cracked.

By the same token, I think that I ought to resign from the Institute (in which I have played so inactive a part) which act I herewith also perform.

Believe me, dear Mr. Johnson, with longing regret,

heroically yours,

WILLIAM JAMES

Cambridge, Mass.

- Quoted from Letters to the Editor. The New York Times (April 16, 1972)

I think you'll agree that this is quite an odd letter to send to someone inviting you to join their organisation - all the more so given that William James had already agreed to be one of the founding members of the American Institute of Arts and Letters some years before.

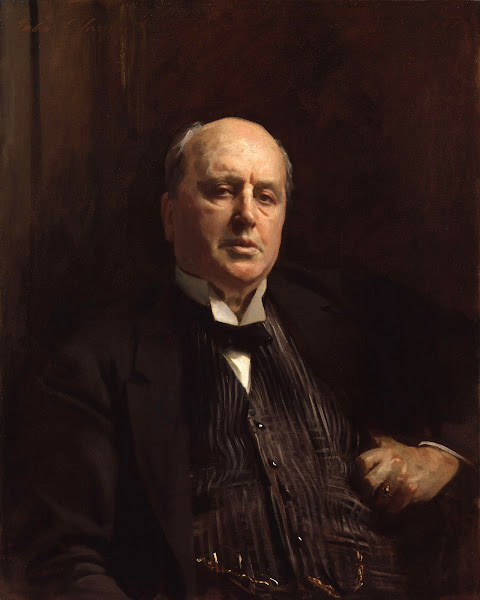

What can have motivated it? Was it really an expression of humility on his part, or was it - as Leon Edel, in his immense, magisterial five-volume biography of Henry James (1953-1972), suggests - because his "younger and shallower and vainer brother" was already in the Academy: i.e. had been asked first?

It's important to stress that William James was 63 at the time, with a worldwide reputation as one of the most influential psychologists and philosophers then living. His "younger and shallower and vainer brother", Henry, was 62, and already seen as a potential candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, for which he was nominated in 1911, 1912, and 1916.

William himself, in context, characterises his own reaction to this insult - an Academy daring to offer priority to his younger brother - as "a bit cracked." His choice of words in describing the possible "James influence" on that institution as "too rank and strong" is also strangely visceral - as if there were something lurking in his family background which literally sickened him.

I've written elsewhere about the mountain of books by and about Henry James collected by me over the years. Which is yet another reason for being surprised at Williams' characterisation of this "Master of nuance and scruple" (in W. H. Auden's phrase), this "great and talkative man," as a "younger and shallower and vainer brother." Vain, yes, perhaps - younger, definitely - but shallow? The mind boggles.

The family tree of the Jameses was more or less as follows ("A shilling life will give you all the facts" - Auden again):

On July 28, 1840, [Henry James Sr. (1811–1882), an American theologican and Swedenborgian mystic], was married to Mary Robertson Walsh (1810–1882), the sister of a fellow Princeton seminarian, by the mayor of New York ... The couple lived in New York, and together had five children:

- William James (1842–1910), a philosopher and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

- Henry James Jr. (1843–1916), an author considered to be among the greatest novelists in the English language ...

- Garth Wilkinson "Wilkie" James (1845–1883) ...

- Robertson "Bob" James (1846–1910) ...

- Alice James (1848–1892), a writer and teacher who became well known for her diary published posthumously in 1934 ...

- Wikipedia: Henry James Sr.

[It could almost pass for a picture of Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes, couldn't it? The article I borrowed this image from is even entitled "Henry James’s Smarter Older Brother." And is it just me, or is there something a little territorial in the way William is trying to tower over his brother, while Henry obligingly tilts his head to try and look as small as possible? It's like two cats establishing precedence when they meet in the backyard.]I guess what interests me most about the James family, though, is not so much the primeval struggle for dominance between the two eldest brothers - it's a psychological commonplace that a second child tries to distinguish him or her self as much as possible from their older sibling. No, it's how that pattern affects the other children that concerns me.

And, yes, I am the youngest in a family of four children: my eldest brother embodies scientific method and logic; the next brother down is completely dedicated to creative writing and the exercise of the existential will; the next down, my sister, was an invalid a little like Alice James, very gifted artistically but unable to deal with the stresses of the workaday world.

So what was left for me, the youngest child? The necessity of avoiding all of these prior choices - in part, or wholly - in order to construct my own independent existence. And how successful have I been? Well, I'm not really in a position to judge: but all I can say is that I believe that your place in the succession, from first to last, has a massive influence on your own individual process of individuation, especially in families with a very dominant ethos: like the Jameses, or the Manns, or (for that matter) the Rosses.

Viktor Mann: Wir waren fünf. Bildnis der Familie Mann [There were five of us: A Mann Family Album] (1949)

Viktor Mann: Wir waren fünf. Bildnis der Familie Mann [There were five of us: A Mann Family Album] (1949)Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann (1840–1891), Lübeck merchant and senator, married Júlia da Silva Bruhns (1851–1923), a German-Brazilian writer. Together they had five children:

- [Luiz] Heinrich Mann (1871–1950), author, president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy of Arts ...

- [Paul] Thomas Mann (1875–1955), author, Nobel Prize for Literature laureate in 1929 ...

- Julia Elisabeth Therese ['Lula'] Mann (1877–1927), married Josef Löhr (1862–1922), banker. She committed suicide by hanging herself at the age of 50.

- Carla [Augusta Olga Maria] Mann (1881–1910), actress. She committed suicide by taking poison at the age of 29.

- Karl Viktor Mann (1890–1949), economist, married Magdalena Nelly Kilian (1895–1962).

- Wikipedia: The Mann Family

[In this picture, taken around 1902, Heinrich seems still to be trying to assert dominance over Thomas. He was, after all, a well-known writer and cultural figure by this time. He'd already published a number of books. Thomas, by contrast, had only published one novel, but it was Buddenbrooks, a massively influential work which would eventually earn him the Nobel Prize. Is he already conscious, here, of biding his time?]You see what I mean about the possible perilous effects of family dynamics? First Carla, then Lula, both sisters, both suicides. Carla was conscious that her acting career was not going as she'd planned: she had little hope left of rivalling her two elder brothers. Whatever miseries drove her to the final act, it cast a long shadow over the whole family. And, then, of course, Lula followed her example seventeen years later.

Thomas Mann's eldest son, Klaus, another writer, who'd striven all his life to get out from under his father's long shadow, would commit suicide in his turn in 1949. He, too, had lived much of his life in a closer-than-close conspiracy with his older sister Erika, a well-known actress married - for passport reasons - to homosexual poet W. H. Auden.

So what am I trying to say about this succession of family tragedies? Nothing to belittle or attempt to 'explain' them, I assure you. Let's return to the Jameses in an effort to make the point a little clearer.

William and Henry had their intense rivalry, co-existing with a genuine love for each other, to keep them going. But what of the rest of the family?

You'll note that both brothers were just of an age to be eligible to join up for the American Civil War (1861-65) - William 19, Henry 18 - when it first broke out. Henry bowed out as the result of an 'obscure hurt', a phrase which generations of critics interpreted to mean some kind of debilitating accident in the genital regions: a little like the hero of Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises (1926). It explained a lot.

However, his biographer Leon Edel has deduced from careful sorting of the evidence that it was far more likely to have been a bad back. In any case, it was enough to spare him from joining the forces in any capacity whatsoever. Was it residual guilt over this that explains his rather patronising review of Walt Whitman's poetry book Drum-taps (1865), a record of the older poet's hospital visits and tending of wounded soldiers during the war? Certainly in later life Henry felt deeply ashamed at having so missed the merits of Whitman's work when he first encountered it.

William, by contrast, was already at Harvard, where he made sure he had enough to do in the scientific arena to make it quite impossible for him to find leisure to take note of the war. Nor was he alone in this. As was the case during the Vietnam war, very few university students in the North actually joined the colours. It was mostly those with manual jobs who marched off to the front.

It was Wilkie and Bob, their two younger brothers, who actually joined up. In her book Biography of Broken Fortunes: Wilkie and Bob, Brothers of William, Henry, and Alice James, Jane Maher traces the sorry saga of their lives thereafter: their abortive attempts to be accepted on their own terms, their business and other failures. Wilkie went bankrupt, was left out of his father's will, and died at the early age of 38. "Unsuccessful at poetry and painting, Bob, an alcoholic with a violent temper, spent many years in asylums, and died at 63, not long before his brother William," as her blurb has it.

But that's not really the whole story. It's important to note here that both brothers were legitimate war heroes, men of honour and principle, and that many of their subsequent difficulties ought properly to be attributed to post-traumatic stress. Both volunteered to serve as officers in Massachusetts' newly-formed Black regiments. As Wilkie put it in a speech to Union Veterans many years later:

When I went to war I was a boy of 17 years of age, the son of parents devoted to the cause of the Union and the abolition of slavery. I had been brought up in the belief that slavery was a monstrous wrong, its destruction worthy of a man’s best efforts, even unto the laying down of life.Wilkie subsequently took part in the heroic (if misguided) Union assault on Battery Wagner in 1863 - the subject of the 1989 civil war film Glory - and was only a few steps behind Colonel Robert Shaw when he died.

Gathering together a knot of men after the suspense of a few seconds, I waved my sword for a further charge toward the living line of fire above us. We had gone then some thirty yards ... Suddenly a shell tore my side. In the frenzy of excitement, it seemed a painless visitation … A still further advance brought us to the second obstruction … The enemy’s fire did not abate for this crossing, and here it was I received my second wound, a canister ball in my foot.He did eventually recover from his wounds, but walked with a limp for the rest of his life.

Bob, too, saw action in the sea islands off coastal South Carolina and Georgia, and nearly died of sunstroke while campaigning in Florida. Little was done by their family after the war to assist them in their transition to civilian life.

When their father decided to buy some land in Florida which he intended to farm with the help of freed slaves, Wilkie was put in charge of the venture. Bob joined him just before local hostility and bad financial conditions put an end to the experiment. They eventually both ended up working for the same railroad in Wisconsin.

Were they failures? In the material sense, perhaps yes. But as Henry remarked (a little guiltily?) of Wilkie:

"He is not particularly successful, as success is measured in this country; but he is always rotund and good-natured and delightful."As for Bob, his alcoholism gradually estranged him from his family, and:- quoted in Carl Swanson, Milwaukee Independent (2021)

In 1885 he returned to Concord to become, in the quarter-century remaining to him, an amiable dilettante, painting, writing poetry and endearing himself as a conversationalist of remarkable powers.Henry James found this brother's conversation, too, "charged with natural life, perception, humor and color ... the equivalent, for fine animation, of William's epistolary prowess."- Edwin M. Yoder, The Washington Post (1986)

What, then, of Alice, the youngest of the James siblings? Well, in many ways she had the oddest destiny of all. She became a professional invalid in the High Victorian manner: like the sofa-bound Signora Neroni in Trollope's Barchester Towers (1857), or (for that matter), the crippled heir of Redclyffe in Charlotte M. Yonge's famous novel.

William, the psychologist, was largely unimpressed by her vapours, but empathetic Henry lavished her with attention. It was mainly for that reason that she shifted her residence to Britain after their parents' death. She also wrote an exceptionally subtle and (at times) acerbic diary, which has become a classic in its own right.

Subsequent biographers and critics, Jean Strouse and Susan Sontag among them, have veered between sympathy and impatience with "Alice-as-icon and Alice-as-victim". She did, however, at least for a time, succeed in putting herself at the centre of the family discourse - which is more than her other two brothers, Wilkie and Bob, ever managed to do.

My own sister, Anne Mairi Ross (1961-1991), a gifted writer and artist, took her own life some three decades ago now. The rest of us rage on. Surviving such family conflicts can be a difficult thing to achieve, and it's therefore with more than an Academic interest that I pore over the histories of the Jameses and the Manns - as well as those of various other creative families, the Bells (Julian and Quentin), the Powyses (John, Theodore, Llewellyn and their eight siblings).

I'm not so naïve as to think that such analogues could ever account for the complexities of any human life, but I'm not sure it's really feasible to ignore the similarities in all these Freudian sibling dramas, either.

I'd like to conclude with a poem from my latest book, The Oceanic Feeling. This one comes from the section called "Family plot," which begins with the following epigraph:

These works of fiction, which seem so full of hostility, are none of them really so badly intended … they still preserve, under a slight disguise, the child’s original affection for his parents. The faithlessness and ingratitude are only apparent.

– Sigmund Freud, ‘Family Romances’ (1909)

Oh br/other!

My eldest brother is flying up

to Auckland

for the weekend

to see my mother

Bronwyn is flying down

to see her sister

in Wellington on Friday

coincidence? hardly

Bronwyn’s younger brother

arrives today

last time we stayed with him

I had a tantrum

and wouldn’t sleep another night

under his roof

I read a thesis recently

on placing far less stress

on Oedipus

the br/other was the term

the author coined

for his new theory

Luke, I am your father!

try your brother

then the sparks will fly

•