I guess there are two questions, really:

- First, why do so many people insist on translating Dante's Divine Comedy (or separate sections of it) into English verse?

- Second, what is it about that Inferno / Purgatory / Paradise three-part structure that has so appealed to writers and artists - plus whatever exactly the lovely Milla Jovovich might be described as - ever since?

Let's start off with some examples of the latter syndrome:

- The Childermass. The Human Age, 1. 1928. Jupiter Books. London: John Calder (Publishers) Limited, 1965.

- Monstre Gai. The Human Age, 2. 1955. Jupiter Books. London: John Calder (Publishers) Limited, 1965.

- Malign Fiesta. The Human Age, 3. 1955. Jupiter Books. London: Calder and Boyars Ltd., 1966.

Horrible old Wyndham Lewis was apparently working on a fourth volume of his interminable "Human Age" when he died, but it's doubtful that any of his characters would ever have got anywhere much anyway.

The whole thing reads more like a vision of hell than of any imaginable Purgatory or Heaven, but then I guess that tends to be the trouble with most of the twentieth-century adaptations of Dante's schema. They start off fine with the Inferno, but then things get increasingly unconvincing the further one moves up the great chain of being.

In this case, the First World War was the initial inspiration (the two main characters have just been killed on the Western front), but as it continued, influences from the Second World War and even the Cold War started to predominate.

- Titus Groan. Illustrated by the author. 1946. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Gormenghast. 1950. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

- Titus Alone. 1959. Rev. ed. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- The Titus Books: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone. 1946, 1950, 1959. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

Is the Gormenghast trilogy linked to Dante in any clear way? Beyond merely being a trilogy, that is?

I suppose that it depends whether one regards the stultified madness of the ancient castle of the Groans as being heavenly or infernal. It's true that one begins to feel a certain nostalgia for its solid certainties amid the chaos of Titus Alone, but its aspect as a bildungsroman does lead Titus to reject the simple alternative of going home at the end of the series.

In that sense, then, like the protagonist of Dante's poem, Titus has achieved a kind of independence by the end of his journey - and has rejected the Luciferian temptations both of Steerpike's anarchy and his mother's orthodoxy. There's probably as much of Paradise Lost in Peake's long epic poem in prose as there is of the Divine Comedy, but that simply serves to underline the seriousness of his teleological concerns.

- Molloy: Roman. 1950. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1967.

- Malone Meurt: Roman. 1951. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1963.

- L’Innommable: Roman. 1953. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1965.

- Three Novels: Molloy; Malone Dies; The Unnamable. 1950, 1951 & 1953. Trans. Samuel Beckett & Patrick Bowles. 1955. An Evergreen Black Cat Book. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965.

The Beckett trilogy seems to approach the problem of progression upwards simply by reversing it. However grovellingly low the abasement of Molloy may seem, it's nothing by comparison with the mollusc-like existence of the Unnamable.

Beckett's work is (of course) a masterpiece, but getting to the end of it requires a kind of courage that not all readers possess. If it weren't for the zany bolts of Hibernian humour that flash out from his prose from time to time (in the English version, at any rate - I'm not so sure about the French), it would be almost literally intolerable. Cheers, Sam!

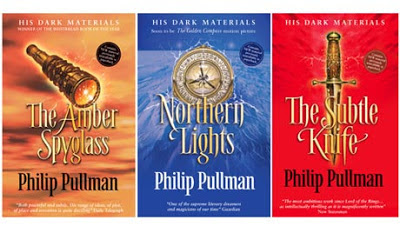

- Northern Lights. [USA: 'The Golden Compass'] His Dark Materials, 1. 1995. Point. London: Scholastic Children’s Books, 1998.

- The Subtle Knife. His Dark Materials, 2. 1997. Point. London: Scholastic Children’s Books, 1998.

- The Amber Spyglass. His Dark Materials, 3. 2000. Point. London: Scholastic Children’s Books, 2001.

- Lyra’s Oxford. Engravings by John Lawrence. 2003. London: Corgi Books, 2007.

Like Peake, Phillip Pullman sets out to rewrite Milton and "justify the ways of God to man" in an entirely new way. Philosophically, he's not really up to the task, but his fictional inventiveness carries one a good deal of the way with him in any case.

There seem to be fragments of a projected fourth volume lurking in the otherwise unremarkable Lyra's Oxford. Whatever it's all really about in the end, though, his work clearly aspires to the status of an secular-eschatological epic.

It's certainly a fine tribute to him that he's managed to achieve second place on the prestigious list of "the top 10 books that people have tried to ban across America" (Guardian Online, 30/9/09) ...

- Lucifer 1: Devil in the Gateway. The Sandman Presents – Lucifer 1-3: 1999 & Lucifer 1-4: 2000. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2001.

- Lucifer 2: Children and Monsters. Lucifer 5-13: 2000. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2001.

- Lucifer 3: A Dalliance with the Damned. Lucifer 14-20: 2001. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2002.

- Lucifer 4: The Divine Comedy. Lucifer 21-28: 2002. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2003.

- Lucifer 5: Inferno. Lucifer 29-35: 2003. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2004.

- Lucifer 6: Mansions of the Silence. Lucifer 36-41: 2003. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2004.

- Lucifer 7: Exodus. Lucifer 42-44, 46-49: 2004. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2005.

- Lucifer 8: The Wolf beneath the Tree. Lucifer 45, 50-54: 2004. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2005.

- Lucifer 9: Crux. Lucifer 55-61: 2005. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2006.

- Lucifer 10: Morningstar. Lucifer 62-69: 2006. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2006.

- Lucifer 11: Evensong. Lucifer – Nirvana: 2002 & Lucifer 70-75: 2006. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2007.

One of my favourite comics ever, Mike Carey's Lucifer series goes way beyond its progenitor, Neil Gaiman's Sandman series, to become its own mad series of riffs on life, death, the afterworld, creation, destruction, retribution, and virtually everything in between. The elegance of his writing is only matched by the absurd ambitiousness of his scheme. It's hard to see how anyone could ever go beyond this avatar of Dante's Commedia ...

- Nights with Giordano Bruno. The REM Trilogy, 1. Wellington: Bumper Books, 2000.

- The Imaginary Museum of Atlantis. The REM Trilogy, 2. Auckland: Titus Books, 2006.

- EMO. The REM Trilogy, 3. Auckland: Titus Books, 2008.

What Jack Ross is doing in this prestigious set of listings is anyone's guess. No doubt he conspired to crash the party somehow. His trilogy of novels about contemporary alienation (focussed, respectively, on insomnia, amnesia and blindness as the vehicles of his three plots) does seem to be trying to tread an upwards path from the "urban inferno of Nights with Giordano Bruno (2000) and the purgatorial stasis of The Imaginary Museum of Atlantis (2006) [to] the closest thing to a paradise his cast of crazies can conceive of – let alone aspire to", as the blurb to EMO puts it.

- Inferno (a poet's novel). New York: OR Books, 2010.

I thought it might be nice to round off the list with some examples of the many, many individual works called "Inferno," "Purgatory," or "Paradise" ...

I have to admit that I haven't read this novel, but it sounds pretty cool: according to the publishers, OR Books, the first sentence reads "“My English professor’s ass was so beautiful,” which sounds like an excellent beginning for any book.

- Purgatory: A Novel. 2008. Trans. John Gaffney (2010)

Author of the classic Santa Evita (1995) and The Perón Novel (1985), this Argentinian journalist and writer died of a brain tumor in January 2010. This was his final novel, published in English shortly after his death. It deals with the dictatorship that afflicted his country between 1976 and 1982, and in particular with the fate of the "disappeared" from those years - territory previously mined by Fernando E. Solanas' beautiful film Sur (1988), as well as Ernesto Sábato's Nunca Más (Never Again): A Report by Argentina’s National Commission on Disappeared People. 1984 (London: Faber / Index on Censorship, 1986).

- Paradiso. 1966. Trans. Gregory Rabassa. 1970.

The only novel by this Cuban poet to reach print in his lifetime, Paradiso deals with "the childhood and youth of José Cemí, told in a highly baroque experimental style, and depicts many scenes which have remarkable resonances with Lezama's own life as a young poet in Havana," according to Wikipedia.

And finally, last but not least, I didn't think I could close my account without mentioning this miniseries within the larger plot arcs of Judge Dredd.

"Purgatory" (written by Mark Millar and drawn by Carlos Ezquerra) appeared in British SF magazine 2000 AD between 8 May and 26 June 1993; its sequel "Inferno" (by Grant Morrison and Carlos Ezquerra) appeared between 3 July and 18 September 1993. Judge Grice is a kind of Lucifer figure, crushed finally (surprise! surprise!) by Dredd himself on his lawmaster bike ...