God gave Noah the rainbow sign,

No more water, the fire next time!- "Mary Don't You Weep" (traditional)

There's an interesting passage in Charlton Heston's autobiography where he discusses working with James Baldwin on the wording of a statement on civil rights to be read out before Martin Luther King's famous March on Washington in August, 1963.

Some of us in the film community decided to organize a group from the arts ... Burt Lancaster, Jim Garner, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, and several others. Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte signed on, but we had no other prominent black performers. You can figure out for yourself who should have been there and wasn't ...I guess, on the fact of it, it's hard to imagine an odder pairing. On the right we have the five-term president of the NRA and unrepentant apologist for second amendment rights, whose gun - as he often specified - could only be taken from "his cold, dead hand"; on the left, the "fringe" civil rights activist (with a Jamesian prose style) pictured above, James Baldwin.

Our job was to get as much ink and TV time as possible. Each of the better known actors had a different media statement. ... They asked me if it was OK for James Baldwin to write my statement; he was a famous black writer, he'd flown over from Paris to join us, and he wanted to make a contribution.

I wasn't crazy about the idea, as a matter of fact. Anything that goes out with my name on it, I write. I always have. Besides, Jimmy Baldwin was on the left fringe of the civil rights movement. The Fire Next Time was the title of his best-known book. I don't know how Dr. King felt about him being there. But the point is, he was there. When an awful lot of good parlor liberals didn't show in case things turned nasty, Jimmy did.

What's more, as a good writer, the speech he wrote for me wasn't what he would've written, but instead very close to what I wanted to say. My only encounter with Jimmy Baldwin was that one meeting, which lasted those few hours. We'd both travelled some little distance to come together, though, as so many hundreds of thousands of people did that day. He died years later in self-imposed exile in Paris. God rest him.- Charlton Heston, In the Arena: The Autobiography (1995): 315-16.

Truth be told, it's probably too odd a juxtaposition to make much sense. One doubts that Heston had actually read The Fire Next Time, as he clearly interprets its actually rather equivocal title as some kind of incitement along the lines of "Burn, Baby, Burn". He seems to have been left with kindly feelings for Baldwin, though, despite their obvious differences. Heston's shift to the extreme right was, in any case, mostly in the future at this stage.

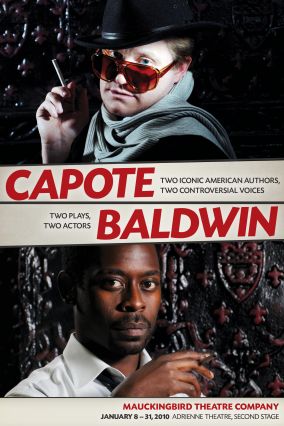

A more fruitful comparison could perhaps be made with Truman Capote, whom I wrote about in a previous post.

Capote and Baldwin were born in the same year, 1924. They were both gay. One was a white Southerner, the other a black Northerner. Both were probably more celebrated for their non-fictional prose than for their fiction: Capote for In Cold Blood (1965), Baldwin for The Fire Next Time (1963) and other hard-hitting essays about race in America. Both died in their sixties, comparatively young: Capote in 1984, Baldwin in 1987.

Michael Ondaatje once claimed: “If Van Gogh was our nineteenth century artist-saint, James Baldwin is our twentieth century one.” Such statements can be more intimidating than they are enlightening. They seem to put Baldwin beyond any purely literary judgement, as if his status as a prophet or "artist-saint" were more important than his innate talent and gift for language.

I'm sure that Ondaatje had no such intention, but just as the otherworldly mantle which has descended upon Holocaust poet Paul Celan makes it increasingly difficult to judge him purely as a poet, so Baldwin has somehow escaped the realm of criticism - which would be fine if it didn't also entail an escape from being considered readable.

Like Chuck Heston, I too must confess to having been put off when I was younger by the title and packaging of Baldwin's most famous book-length essay, The Fire Next Time. Now it looks to me like a striking piece of sixties book-design, with a charming cover photograph and a bold choice of font. When I looked at it as a teenager, though, it looked dauntingly political. I had no idea, back then, of the wonderful interweaving of the personal and the philosophical which distinguishes almost all of Baldwin's non-fictional writings.

It wasn't, in fact, until some years later, when an angry (and - let's face it - somewhat stoned) friend informed me that anyone who hadn't read The Autobiography of Malcolm X could not consider themselves educated that I tried to redress this bias. And it is a wonderfully gripping read. Whether this can be attributed primarily to Alex Haley or to Malcolm himself is an interesting question, but the answer is largely immaterial. The vividness and narrative drive of the book itself never flags.

Given the prejudices of the time, it's perhaps no surprise that the 'Malcolm X' feature film script James Baldwin was commissioned to write in the late 1960s never actually reached the screen. It would not be till 1992, when Spike Lee undertook the task, that a Malcolm X bio-pic would actually seem possible.

Baldwin's script is a fine piece of writing in itself, but by the time I finally got round to reading it I'd already begun to get acquainted with Toni Morrison's edition of his Collected Essays, published in the canonical Library of America series in the late 1990s. The Auckland public library had a copy, which I took out repeatedly before ordering one of my own so I could read it from cover to cover, chronologically, rather than coninuing to dip into it piecemeal.

There's never been much doubt cast on the merits of his work as an essayist (except possibly by the victims of some of his earlier critical pieces). The Devil Finds Work, his intensely autobiographical meditation on Hollywood movies, is perhaps the most accessible and revealing of the separate book-length essays, but really you could start with any one of them. Even Truman Capote was forced to acknowledge the power and drive of his non-fiction.

When it comes to his fiction, however, the response is more mixed. Here's a quote from the movie Capote, inspired by Gerald Clarke's 1988 biography:

Truman Capote:

I had lunch with Jimmy Baldwin the other day.

Party date:

How is he?

Truman Capote:

He's lovely, he's a lovely man. And he told me the plot of his new book. And he said, "I just wanted to make sure it's not one of those problem novels," you know. And I said, "Jimmy. Your book is about a Negro homosexual who's in love with a Jew. Wouldn't you call that a problem?"

On the other hand, the 2018 movie If Beale Street Could Talk, based on his penultimate novel, got rave reviews. One critic described it as "a terrific film, as sinewy as it is sensuous, interweaving stark social-realist themes of prejudice, oppression and imprisonment with a poetic evocation of love, loss and, ultimately, transcendence."

“Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street,” states the opening quotation from Baldwin, citing “the impossibility and the possibility, the absolute necessity, to give expression to this legacy”.The point is, perhaps, that there will always be another Baldwin to discover alongside the activist. The enduring value of his work will depend on the subtlety and emotional truth of his fiction just as much as it does on the continuing cogency of his political message.

There's no denying his status as one of the finest prose stylists in American literature. The point is that this doubling of the self means that his work remains alive and relevant in a way that cannot honestly be claimed for Capote, Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal or indeed most of his more media-friendly contemporaries.

- Fiction:

- Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953)

- Giovanni's Room (1956)

- Another Country (1962)

- Going to Meet the Man (1965)

- Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968)

- If Beale Street Could Talk (1974)

- Just Above My Head (1979)

- Early Novels & Stories. Ed. Toni Morrison (1998)

- Early Novels & Stories. Ed. Toni Morrison. The Library of America, 97. [‘Go Tell It on the Mountain’, 1953; ‘Giovanni's Room’, 1956; ‘Another Country’, 1962; ‘Going to Meet the Man’, 1965]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1998.

- Later Novels. Ed. Darryl Pinckney (2015)

- Later Novels. Ed. Darrell Pinckney. The Library of America, 98. [‘Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone’, 1968; ‘If Beale Street Could Talk', 1974; ‘Just Above My Head’, 1979]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2015.

- Notes of a Native Son (1955)

- Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961)

- The Fire Next Time (1963)

- No Name in the Street (1972)

- The Devil Finds Work (1976)

- The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985)

- The Price of the Ticket (1985)

- Collected Essays. Ed. Toni Morrison (1998)

- Collected Essays. Ed. Toni Morrison. The Library of America, 98. [‘Notes of a Native Son’, 1955; ‘Nobody Knows My Name,’ 1961; ‘The Fire Next Time’, 1963; ‘No Name in the Street’, 1972; ‘The Devil Finds Work’, 1976]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1998.

- The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings (2010)

- Baldwin for Our Times: Writings from James Baldwin for an Age of Sorrow and Struggle. Ed. Rich Blint (2016)

- The Amen Corner (1954)

- Blues for Mister Charlie (1964)

- [with Alex Haley] One Day, When I Was Lost (1972)

- One Day, When I Was Lost: A Scenario based on The Autobiography of Malcolm X. 1972. Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993.

- A Lover's Question. Les Disques Du Crépuscule, TWI 928–2 (1990)

- Jimmy's Blues (1983)

- Jimmy's Blues and Other Poems (2014)

- Little Man Little Man: A Story of Childhood. Illustrations by Yoran Cazac (1976)

- Nothing Personal. Photographs by Richard Avedon (1964)

- [with Margaret Mead] A Rap on Race (1971)

- [with Nabile Farès] A Passenger from the West (1971)

- [with Nikki Giovanni] A Dialogue (1973)

- [with Sol Stein] Native Sons (2004)

- David Adams Leeming. James Baldwin: A Biography (1994)

- James Campbell. Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin (2021)

Non-fiction:

Plays / Screenplays / Audio:

Poetry:

For Children:

Collaborations:

Secondary:

•