The World of Charles Dickens

[photographs: Bronwyn Lloyd (2022)]

The World of Charles Dickens

[photographs: Bronwyn Lloyd (2022)]

For Christmas 2021, Bronwyn gave me a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle called

The World of Charles Dickens. It took us almost a week to complete it. Above you can see me putting in the very last piece. Below is an earlier stage of the process.

Opening stages

Opening stages

Mind you, I did have help. Zero was always ready to oblige with advice, and the fact that Bronwyn is holding the camera doesn't mean that she didn't do more than her fair share of wrestling with this fiendish conundrum, either.

Jack & Zero

Jack & Zero

It was a bit of a relief to get it done, to tell you the truth. I'd forgotten just how tricky it could be to complete a large jigsaw of this kind. My mother used to bring them home for us when we were kids. She volunteered in the local opportunity shop, and it went against her conscience to sell any donated goods which hadn't been thoroughly checked in advance. They almost invariably had a piece or two missing, which has left me with an abiding syndrome about the final stages of assembly.

The field of battle

The field of battle

This particular puzzle - fresh out of the box - did prove to be complete. That hadn't stopped me from anticipating the worst. Bronwyn is of a sunnier disposition, fortunately.

A great many of the characters included in the design were obvious enough: Mr. Pickwick and Sam Weller (

The Pickwick Papers); Lizzie Hexham rowing her father down the Thames (

Our Mutual Friend); the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future (

A Christmas Carol); Jo the crossing-sweeper being accosted by Lady Dedlock (

Bleak House) ...

A great many of the others I'd never have guessed, though. I did spot the rowboat with Pip, Herbert Pocket, and Magwitch the convict from

Great Expectations, but Estella and Miss Havisham were less clear to me. A great many of the 70-odd characters included just looked like typical Victorians in breeches and bonnets. But an immense amount of ingenuity had been spent on the layout and colouring of the picture - so many windows and roofs to identify! Not to mention fields, bushes and lawns ... In fact, if it hadn't been for the Thames running through it, the puzzle might well have proved insuperable.

It did get me thinking about Dickens in general. In an earlier post about my

Grandmother and her book collection, I mentioned the 22-volume set of his works which she and my grandfather painstakingly saved up for in the 1930s, and which has eventually made its circuitous way to my own bookshelves.

I can't claim to have read all of it. I

have read his fourteen full-length novels (as well as the unfinished

Edwin Drood), and - at one time or another - most of the other miscellaneous fiction he published. But some of the compilations of journalism and other occasional pieces (

Sketches by Boz,

Reprinted Pieces, and

The Uncommercial Traveller, for instance) have hitherto evaded my quest for completeness.

Which is one reason I decided that a good project for Summer might be to remedy that. I recently read a

New Yorker article on just such an attempt, by a writer called Brad Leithauser. I'd note, though, that he wrote it while he was "

nearly finished [my emphasis]; only

The Old Curiosity Shop and

The Mystery of Edwin Drood remain."

Given that this admission shows that he hadn't been reading chronologically - which is, in my opinion, the only way of gleaning much profit from a trawl through an author's collected works - and given his almost exclusive focus on

David Copperfield at the expense of Dicken's obscurer fiction, I must confess to a certain scepticism about the thoroughness of Leithauser's coverage - not to mention his conclusion that "my favorite Dickens is mostly the world’s favorite Dickens."

His choice of three books - respectively,

A Christmas Carol,

A Tale of Two Cities, and the above-mentioned

David Copperfield - as "all but flawless in their chosen genres" is, I suppose, fair enough. But is it just a perverse taste for the recondite which makes me find that a little disappointing? What of the baroque splendours of

Our Mutual Friend? What of the exuberant frenzies of

Nicholas Nickleby or

Pickwick? What of such proto-M. R. James-like, pared-back ghost stories as "The Signalman" or "The Trial for Murder"?

Dickens's work as a whole seems to constitute - for me at least - a curious combination of social realism and gothic extremity. His actual political opinions had a reactionary tinge which make them less than palatable today - but his emotional engagement with the realities of poverty and want are still powerful and moving even at this distance in time.

He was horrible to his wife, duplicitous about his mistress, dictatorial to his children, and intensely demanding of his friends. He was simultaneously tirelessly productive, endlessly energetic, and immensely self-destructive. It's not so much surprising that he burned out at the early age of 58 as that he was able to last that long in the first place!

One of the few good reasons I've ever heard for wanting there to be a next world, though, is the opportunity to read the conclusion to the unfinished

Mystery of Edwin Drood, which I presume that he will have cranked around to completing by now.

There are many biographies. At times it can seem as if the majority even of bookish people are far less keen on reading him than reading

about him. The original Victorian biography by John Forster is still an essential source, and I must confess, too, to a soft spot for Edgar Johnson's exhaustive two-volume account of 1952.

I'm not myself a great admirer of Peter Ackroyd's strange biography-with-fictional-interludes, though it certainly has its moments. A far more significant contribution to scholarship came from Claire Tomalin's

The Invisible Woman: a biography of Dickens's mistress Nelly Ternan, which appeared in the same year, 1990.

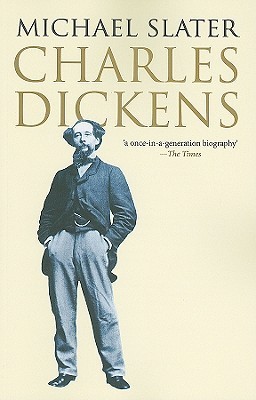

She's followed this up since with a full-dress biography of Dickens, perhaps meant as a riposte to Michael Slater's, also pictured above. Slater is, after all, a bit of a Ternan-sceptic, witness his book

The Great Charles Dickens Scandal (2012), which takes issue with many of Tomalin's points.

In any case, whatever your views on this or other contentious points, you won't find too much difficulty in finding material to your taste in the vast untidy field of Dickens scholarship. Even the famously critical F. R. Leavis finally decided to admit him to the fold of the 'great tradition' in English fiction.

There was a bit of mini Dickens revival in 2005, with Andrew Davies' magisterial TV adaptation of

Bleak House. This was a far less mannered and parodic take on the dramatic intensity of Dickens' later novels than had hitherto been seen on British TV.

Davies followed it up with an equally brilliant and star-studded adaptation of

Little Dorrit a couple of years later, with a breathtaking performance in the title role by a young Claire Foy. This also had the not unfortunate by-product of supplanting Christine Edzard's ambitious but not entirely successful double-film version of 1987.

At the time this seemed like the best one could expect when it came to putting one of Dickens' most complex novels on screen. Davies seemingly effortlessly surpassed it, though there were certainly some memorable moments in the earlier version.

I've provided a list, below, of the Dickens films and TV serials I happen to have to hand on DVD. I guess, for me, the highpoints would have to be David Lean's

Great Expectations (1946) and

Oliver Twist (1948). I also enjoyed the Dirk Bogarde version of

A Tale of Two Cities (1958), though, as well as some of the classic BBC adaptations of such novels as

The Pickwick Papers (1985),

Martin Chuzzlewit (1994) and

Our Mutual Friend (1998).

Another TV show which had a huge influence on me in my teens was the 13-part

Dickens of London. Roy Dotrice made a valiant effort to play both the young and older Dickens, but the sheer ambition of the attempt still seems astonishing now. I was very glad to have the chance to see it again. The episode where Dickens meets Edgar Allan Poe, and reenacts with him a strange version of "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar", made a great impression on me at the time.

Collected Editions:

- The Works of Charles Dickens. 22 vols. Dunedin & Wellington: A. H. Reed, 1931:

- Sketches by Boz: Illustrative of Everyday Life and Everyday People (1836-39)

- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836-37)

- Oliver Twist, or The Parish Boy’s Progress (1837-39)

- The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1839)

- The Old Curiosity Shop (1841)

- Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of ‘80 (1841)

- American Notes & Pictures from Italy (1842 & 1846)

- The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44)

- Christmas Books: A Christmas Carol / The Chimes / The Cricket on the Hearth / The Battle of Life / The Haunted Man (1843, 1844, 1845, 1846 & 1848)

- Dealings with the Firm of Dombey & Son: Wholesale, Retail, and for Exportation (1848)

- The Personal History of David Copperfield (1850)

- A Child’s History of England (1851-53)

- Bleak House (1853)

- Hard Times / Hunted Down / Holiday Romance / George Silverman's Explanation (1854 & 1867)

- Little Dorrit (1857)

- Reprinted Pieces: Also The Lamplighter; To Be Read at Dusk; Sunday Under Three Heads (1858)

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Great Expectations (1860-61)

- The Uncommercial Traveller (1860-69)

- Our Mutual Friend (1864-65)

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood & Master Humphrey’s Clock (1870 & 1840)

- Christmas Stories: From “Household Words” and “All The Year Round” (1874)

- The 'Daily News' Memorial Edition. 19 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, Ld, n.d. [c.1900-1910]:

- Sketches by Boz: Illustrative of Everyday Life and Everyday People. Illustrated by George Cruickshank (1836-39)

- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Phiz et al (1836-37)

- [Oliver Twist / A Tale of Two Cities (1837-39 & 1859)]

- [The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1839)]

- [The Old Curiosity Shop (1841)]

- Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of ‘80. Illustrated (1841)

- American Notes / Pictures from Italy / A Child’s History of England (1842, 1846 & 1851-53)

- The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated (1843-44)

- Christmas Books: A Christmas Carol / The Chimes / The Cricket on the Hearth / The Battle of Life / The Haunted Man & Hard Times. Illustrated (1843, 1844, 1845, 1846, 1848 & 1853)

- Dealings with the Firm of Dombey & Son: Wholesale, Retail, and for Exportation. Illustrated (1848)

- The Personal History of David Copperfield. Illustrated (1850)

- [Bleak House (1853)]

- Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Phiz (1857)

- [Great Expectations / The Uncommercial Traveller (1860-61, 1860-69)]

- Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone (1864-65)

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood & Reprinted Pieces. Illustrated (1870 & 1858 40)

- Christmas Stories: From “Household Words” and “All The Year Round” & Other Stories: Master Humphrey’s Clock / Hunted Down / Holiday Romance / George Silverman's Explanation. Illustrated (1874, 1840, 1867)

- [The Dickens Dictionary, by Gilbert A. Pierce & William A. Wheeler (1880)]

- [Life of Charles Dickens, by John Forster (1872-74)]

- Dickens, Charles. The Annotated Dickens. Ed. Edward Giuliano & Philip Collins. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986.

- The Pickwick Papers (1836-37); Oliver Twist (1837-39); A Christmas Carol (1843); Hard Times (1854)

- David Copperfield (1849-50); A Tale of Two Cities (1859); Great Expectations (1860-61)

Novels:

- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. 1836-37. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Penguin English Library. 1972. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Oliver Twist. 1837-39. Ed. Peter Fairclough. Introduction by Angus Wilson. Penguin English Library. 1966. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

- Oliver Twist. 1837-39. Ed. Kathleen Tillotson. 1966. The Clarendon Dickens. Ed. John Butt & Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

- Nicholas Nickleby. 1839. Ed. Michael Slater. Penguin English Library. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

- The Old Curiosity Shop. 1841. Ed. Angus Easson. Introduction by Malcolm Andrews. Penguin English Library. 1972. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Barnaby Rudge. 1841. Ed. Gordon Spence. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973.

- Martin Chuzzlewit. 1843-44. Ed. P. N. Furbank. Penguin English Library. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

- Dombey and Son. 1848. Ed. Peter Fairclough. Introduction by Raymond Williams. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- The Personal History of David Copperfield. 1850. Ed. Trevor Blount. Penguin Classics. 1966. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

- Bleak House. 1853. Ed. Norman Page. Introduction by J. Hillis Miller. Penguin English Library. 1971. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- Hard Times for These Times. 1854. Ed. David Craig. Penguin Classics. 1969. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

- Little Dorrit. 1857. Ed. John Holloway. Penguin Classics. 1967. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

- A Tale of Two Cities. 1859. Ed. George Woodcock. Penguin English Library. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

- Great Expectations. 1861. Ed. Angus Calder. Penguin English Library. 1965. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Great Expectations. 1860-61. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. The Works of Charles Dickens, National Edition, Volume XXIX. London: Chapman & Hall Ltd., 1907.

- Our Mutual Friend. 1864-65. Ed. Stephen Gill. Penguin English Library. 1971. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984.

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood. 1870. Ed. Arthur J. Cox. Introduction by Angus Wilson. Penguin English Library. 1974. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976.

Shorter fiction:

- The Christmas Books. Vol. 1: A Christmas Carol / The Chimes. 1843 & 1844. Ed. Michael Slater. Penguin English Library. 1971. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- The Christmas Books. Vol. 2: The Cricket on the Hearth / The Battle of Life / The Haunted Man. 1845, 1846 & 1848. Ed. Michael Slater. Penguin Classics. 1971. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

- The Annotated Christmas Carol: A Christmas Carol in Prose. 1843. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. Illustrations by John Leech. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- [with Wilkie Collins] The Wreck of the Golden Mary. 1856. Illustrated by John Dugan. Venture Library. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1961.

- Selected Short Fiction. Ed. Deborah A. Thomas. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976.

- Readings from Dickens. Ed. Emlyn Williams. London: The Folio Society, 1953.

- Sikes and Nancy and Other Public Readings. Ed. Philip Collins. 1975. The World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Non-fiction:

- Sketches by Boz. 1839. Ed. Dennis Walder. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1995.

- American Notes. 1842. Ed. Patricia Ingham. 2000. Rev. ed. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2004.

- Pictures from Italy. 1846. Ed. Kate Flint. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998.

- The Life of Our Lord: Written Expressly for His Children by Charles Dicken. 1849. Foreword by Lady Dickens. 1934. London: Associated Newspapers Ltd., 1934.

- Miscellaneous Papers. 1912. The Works of Charles Dickens: Complete Works. Centennial Edition. 2 vols. Geneva: Heron Books, 1970.

- Selected Journalism 1850-1870. Ed. David Pascoe. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1997.

- My Early Times. Ed. Peter Rowland. London: The Folio Society, 1988.

- The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens' Journalism. Ed. Michael Slater. 4 vols. London: J. M. Dent, 1994-2000.

- Dickens’ Journalism: Sketches by Boz and Other Early Papers, 1833-39. Illustrations by George Cruikshank et al. 1994. Phoenix Giants. London: The Orion Publishing Group, 1996.

- Dickens’ Journalism: ‘The Amusements of the People’ and Other Papers: Reports, Essays and Reviews, 1834-51. 1996. London: J. M. Dent, 1997.

- Dickens’ Journalism: ‘Gone Astray’ and Other Papers from Household Words, 1851-59. The Orion Publishing Group Ltd. London: J. M. Dent, 1999.

- [with John Drew] Dickens’ Journalism: The Uncommercial Traveller and Other Papers, 1859-1870. The Orion Publishing Group Ltd. London: J. M. Dent, 2000.

Poetry & Drama:

- Dickens, Charles. Complete Plays and Selected Poems. 1970. London: Vision Press Ltd., 1974.

Edited:

- Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. 1838. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: George Routledge and Sons, n.d. [c.1879].

- Stott, Andrew McConnell. The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi. 2009. Edinburgh: Canongate Books Ltd., 2010.

Letters:

- The Letters: 1833-1870. Ed. His Sister-in-Law & His Eldest Daughter. 1893. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1903.

- The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1839. Ed. Madeline House & Graham Storey. The Pilgrim Edition. Vol. 1 of 12. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1965.

Dramatisations:

- The Charles Dickens Collection (2012). 3-DVD set:

- Great Expectations, dir. David Lean, writ. David Lean, Anthony Havelock-Allan, Cecil McGivern, Ronald Neame & Kay Walsh – with John Mills, Bernard Miles, Finlay Currie, Jean Simmons, Martita Hunt, Alec Guinness, Valerie Hobson – (UK, 1946)

- Oliver Twist, dir. David Lean, writ. David Lean & Stanley Haynes – with Kay Walsh, John Howard Davies, Alec Guinness – (UK, 1948)

- A Tale of Two Cities, dir. Ralph Thomas, writ. T. E. B. Clarke – with Dirk Bogarde, Dorothy Tutin – (UK, 1958)

- Dickens of London: 13-part miniseries, created by Wolf Mankowitz & Marc Miller – with Roy Dotrice, Simon Bell, Gene Foad, Lois Baxter, Christine McKenna – (UK, 1976). 4-DVD set.

- The Charles Dickens Collection: 8 Classic BBC Adaptations. 12-DVD set:

- The Pickwick Papers – with Nigel Stock, Clive Swift, Patrick Malahide – (UK, 1985)

- Oliver Twist – with Lysette Antony, Ben Rodska, Miriam Margolyes, Eric Porter, Michael Attwell – (UK, 1985)

- A Christmas Carol – with Michael Hordern, John Le Mesurier, Bernard Lee – (UK, 1977)

- Martin Chuzzlewit – with Paul Scofield, John Mills, Tom Wilkinson, Pete Postlethwaite, Julia Sawlaha, Maggie Steed – (UK, 1994)

- David Copperfield – with Daniel Radcliffe, Bob Hoskins, Maggie Smith, Nicholas Lyndhurst, Cherie Lunghi, Ian McKellan, Ciaran McMenamin – (UK, 1999)

- A Tale of Two Cities – with Paul Shelley, Nigel Stock, Sally Osborne – (UK, 1980)

- Great Expectations – with Ioan Gruffudd, Charlotte Rampling, Bernard Hill – (UK, 1999)

- Our Mutual Friend – with Paul McGann, Keeley Hawes, Anna Friel, Peter Vaughan, Timothy Spall – (UK, 1998)

- Charles Dickens: 200th Anniversary Collection (2012). 9-DVD set:

- Bleak House, dir. Justin Chadwick & Susanna White, writ. Andrew Davies – with Denis Lawson, Anna Maxwell Martin, Patrick Kennedy, Carey Mulligan, Gillian Anderson, Charles Dance, Alun Armstrong, Timothy West, Burn Gorman, Harry Eden – (UK, 2005)

- Oliver Twist, dir. Coky Giedroyc, writ. Sarah Phelps – with William Miller, Adam Arnold, Tom Hardy, Timothy Spall, Julian Rhind Tutt – (UK, 2007)

- Little Dorrit, dir. Adam Smith, Dearbhla Walsh, & Diarmuid Lawrence, writ. Andrew Davies – with Claire Foy, Matthew Macfadyen, Tom Courtenay, Judy Parfitt – (UK, 2008)

- Great Expectations, dir. Brian Kirk, writ. Sarah Phelps – with Ray Winstone, Gillian Anderson, Douglas Booth, Vanessa Kirby, David Suchet – (UK, 2011)

- The Man Who Invented Christmas, dir. Bharat Nalluri, writ. Susan Coyne (based on the book by Les Standiford) – with Dan Stevens, Christopher Plummer, Jonathan Pryce – (Ireland / Canada, 2017).

Secondary:

- Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens' London: An Imaginative Vision. London: Headline Book Publishing PLC., 1987.

- Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson Ltd., 1990.

- Butt, John, & Kathleen Tillotson. Dickens at Work. 1957. London & New York: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1982.

- Chesterton, G. K. Charles Dickens. 1906. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1919.

- Chesterton, G. K. Criticisms and Appreciations of Charles Dickens’ Works. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. / New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1911.

- Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. With Thirty-Two Illustrations. 1872-74. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press, n.d.

- Hardwick, Michael & Mollie. The Charles Dickens Encyclopedia. 1973. An Omega Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1976.

- Hibbert, Christopher. The Making of Charles Dickens. 1967. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- House, Humphry. The Dickens World. 1941. London: Geoffrey Cumberlege / Oxford University Press, 1950.

- Johnson, Edgar. Charles Dickens. His Tragedy and Triumph. 2 vols. New York: Simon and Schuster Inc., 1952.

- Pope-Hennessy, Una. Charles Dickens: 1812-1870. 1945. London: The Reprint Society, 1947.

- Slater, Michael. Dickens and Women. 1983. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1986.

- Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. 2009. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Slater, Michael. The Great Charles Dickens Scandal. 2012. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Tillotson, Kathleen. 'Dombey and Son.' In Novels of the Eighteen-Forties. 1954. Oxford Paperbacks. London: Oxford University Press, 1961.

- Tomalin, Claire. The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens. 1990. London: Penguin, 1991.

- Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. 2011. London: Penguin, 2012.

- Wilson, Angus. The World of Charles Dickens. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

•

The World of Charles Dickens

[photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd (2022)]

The World of Charles Dickens

[photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd (2022)]