From the places with their docile English names, Huntly, Hamilton, Cambridge, he drove on, to Tirau, Putaruru, up into the central hills, the remoteness, where there were few names or places, and thought of a story he had once read called The Heart of Darkness: about how in some central African jungle the Europeans had come to exploit and destroy and had been in their turn destroyed. He still did not really believe in any abstract forces which lay in all this, waiting like that; but the land did have some power to make human beings seem futile, he saw this in the way the road was just a small mark on the face of the hills and the thick forest, a futile and weak gesture, and in a sense it was almost amusing to think of the precariousness of human control over everything: civilisation just a gesture on the edge: and in the center, still, the same heart of darkness.- Craig Harrison: Broken October: 135.

•

When I first went to university, in 1980, I was intending to study history.

None of the papers available in first year really enthused me, though, so instead I drew up an eclectic assortment of courses designed to cover as many other options as possible. You were supposed to do 8 papers in your first year, and 7 in each of the successive years.

So far as I can recall, my 8 included two papers in Ancient History (Roman and Egyptian), two papers in Italian (an introduction to the language and the culture), two papers in English (Chaucer & Shakespeare and Twentieth Century Literature), a paper in Latin, and another paper in Anthropology.

English was not at the top of my list, but - somehow - it was what I ended up specialising in (my other majoring subject was Italian). Part of that was due to the fact that I really enjoyed the lectures and tutorials on modern literature.

I was a ridiculous little know-it-all, who'd already read most of the authors prescribed for us (Ulysses rather than Dubliners, all of Hardy's novels rather than just a few selections from his poetry, etc. etc.) I therefore expected my views to prevail in argument. They did not. Again and again I was forced to admit that even though I had wolfed down so many books, my interpretative skills were lamentably undeveloped.

The lectures that stick in my mind most of all were a couple of guest appearances by Mervyn Thompson, who talked to us about Craig Harrison's then-recent play Tomorrow Will Be a Lovely Day (1975). I had no idea who Mervyn was, and had the snobbish disdain for New Zealand writers common to those who'd spent too much time trying vainly to keep up with what was 'in' in Europe and America.

The theme of Mervyn's first lecture was the necessity for New Zealand writers to express their own realities, by using local themes and details of local life - and to stop relying on views from elsewhere. I found this an interesting view, but felt compelled to approach him afterwards to acquaint him with the somewhat contrasting attitudes of Jorge Luis Borges in his classic essay 'The Argentine Writer and Tradition' (1951).

Borges advises his countrymen to eschew any self-conscious use of 'local colour'. Instead, he pontificates:

We should feel that our patrimony is the universe; we should essay all themes, and we cannot limit ourselves to purely Argentine subjects in order to be Argentine; for either being Argentine is an inescapable act of fate — and in that case we shall be so in all events — or being Argentine is a mere affectation, a mask.My efforts to explain all this to Mervyn were not very successful, partially because another enthusiast from the audience also wanted to discuss the lecture with him at the same time. I suppose what remains with me from this rather farcical scene is the courtesy and kindness he showed in trying to speak to each of us without privileging one over the other.

The other exciting aspect of his lecture - there was a follow-up one the next week - was the inside information he included in his discussion of the play. 'In our production we did so-and-so,' he would say. 'Philip Sherry played the news reader at this point in the play ...'

This was heady stuff! The thought of actually meeting and hobnobbing with writers, being involved with them in their artistic endeavours was something quite alien to someone who'd grown up on books of anecdotes about Eliot, Joyce, Pound, Woolf and all the other modernist giants.

Mervyn had his own strange destiny to work out still at that point. In 1984, the year of Coaltown Blues, he was abducted, stripped and tied to a tree with a 'Rapist' sign hung round his neck by a group of feminist protestors who were taking revenge for a student he had allegedly abused. Mervyn admitted the relationship, but claimed it had been concensual.

The bizarre details of his public shaming were borrowed from his friend Renee's play Setting the Table (1982), which he had originally assisted in workshopping. Talk about life imitating art! This was life doing so in the most deliberate fashion possible.

Some people would have submitted to the pressure to stay silent at this point. He was, after all, a lecturer at Auckland University, no friend as an institution - then or now - to loud controversies. Mervyn, however, chose to speak out, writing a long article about the event in the Listener.

What shocked me most about it, though, at the time - how naive of me! - was the fact that the Maidment Theatre almost immediately closed down his play. What happened to innocent until proven guilty, I wondered? No, the moment the flag went up, he became a non-person straight away.

But I've strayed a long way from Craig Harrison and his play. Harrison was then an English lecturer at Massey University, and was rising rapidly in the New Zealand literary scene. I met him years later, in 1991, when I was employed as a tutor down in Palmerston North.

I'd heard he was a bit stand-offish from some of the other teachers around the Department. I'd noticed myself that he never attended Departmental meetings - though given that most of these ended with strident confrontations between the touchier members of the staff, who seemed to make a point of running out of the room in extreme high dudgeon, a different candidate each week - I could see his point about that.

The bold approach usually works best on these occasions, I find. I came up to him in the staffroom while he was making a cup of tea, and said that I'd just finished reading his book Grievous Bodily, and how much I'd enjoyed it.

What was it Mark Twain said? The best way to an author's heart is to tell them you've just read their book. If you really want to seal the deal, tell them you've (bought and) read all of them!

We had a great old natter after that: about Grievous Bodily (almost cripplingly funny, I found it at the time), The Quiet Earth, and various other matters. He told me that he was determined never to publish another novel.

"Whyever not?" I asked.

"Because of the editors. I spent so much time arguing with them over this book that it took all the enjoyment out of it. They insisted I write the word 'biro pen' with a capital letter because it was originally named after its creator, László Bíró. I told them that everyone writes it with a small letter now. They wouldn't give in ..."

And, you know, it's true. He didn't put out another novel after that for another 25 years, not until that amusing YA romp The Dumpster Saga in 2007.

Back to the Future. That's one way of putting it. Another phrase, devised by Frederick Pohl as the title of his autobiography, is - The Way The Future Was:

One of the problems with dystopian visions set in the near future is that they date so quickly. Harrison's play Tomorrow Will Be a Lovely Day was staged for the first time in 1975. It was quickly followed by his 'novelisation' of the script, Broken October, in 1976. That is, if that was the order they were written in - maybe the novel actually preceded the play?

The rapid decay from a smug, paternalist democracy to a police state rather akin to General Pinochet's Chile takes place - in Harrison's grim vision - over a few months of fictional time in the - then distant - year of 1985.

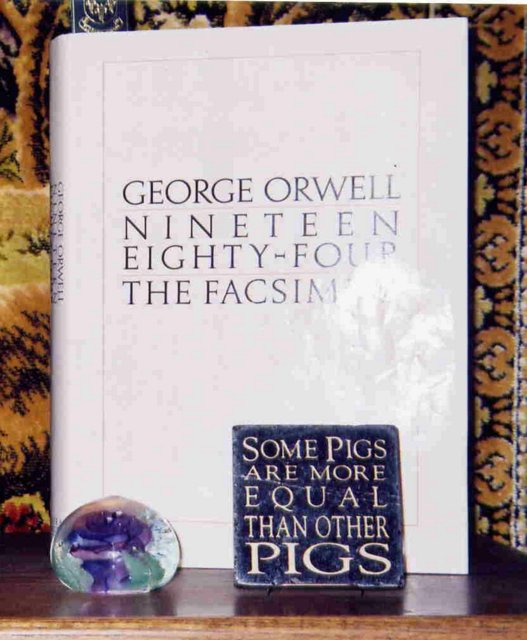

Not that there's anything neutral in that choice of dates. Just like Anthony Burgess a couple of years later, Harrison meant to link his bow-by-blow account of what just might happen in Aotearoa New Zealand if we allowed our already lamentable racial abuse and human rights record to decay any further to George Orwell's already classic masterpiece 1984:

Nineteen Eighty-Four may, then and now, be considered a classic - but is it really particularly prescient? is that the true source of its appeal?

Clearly, when we finally reached that canonical year (some 35 years ago now), things were not precisely as described in Orwell's novel - though his Eurasia, Eastasia and Oceania giant states did bear a strong resemblance to the triple power blocks of the USA, Russia, and emergent China.

Burgess's update is shabbier, more satirical, less starkly totalitarian. To be honest, it's a bit difficult to read now - time has not been kind to most of his late novels, only A Clockwork Orange and (perhaps) The Doctor is Sick retaining a bit of their counter-culture punch.

How, then, are we to read Harrison's own localised vision of the year after 1984? Most of what he foresaw didn't happen, of course. The election of a Labour Government in 1984 meant the end of ANZUS as a result of our new nuclear-free policy. The brutal economic warfare of the late 1980s chose a more bureaucratic and less direct way of grinding the people's face in the dust.

If one were to see it as one of (at least) three 1970s fictional visions of New Zealand in the near future: Broken October alongside C. K. Stead's Smith's Dream (1971) and M. K. Joseph's The Time of Achamoth (1976), it's definitely the gloomiest of the three.

Smith's Dream, compellingly filmed as Sleeping Dogs (1977), has at least the advantage of an initial pastoral vision to put alongside the brutal repression of the new regime. There's a certain artistic advantage in having a single protagonist, too.

M. K. Joseph's innate conservatism made it hard for him to hit out unequivocally at the forces of 'order' in his own complex blended vision of a past constantly interfusing into (and interfering with) the present.

Alongside these two others, Harrison's novel reads rather like a work of popular history: What went wrong with the revolution? Come to think of it, it does have certain analogies with more recent events such as the Arab Spring. His two contrasting Maōri protagonists, Rangi Tamatea and Rewi Waitoa, never really come to life, any more than their respective pakeha girlfriends Helen the nurse and Anne the rich party girl.

His play, Tomorrow Will Be a Lovely Day, has, on the other hand, the advantage of conciseness - as well as a clever use of music and lighting to shift from place to place in the dreamtime of his imagination.

Scott Hamilton, in a 2007 blogpiece on the differences between the Stead's and Harrison's novels, characterises them as follows:

Smith's Dream is bleak, as dystopias tend to be, but it is also abstract, ahistorical, and somewhat mysterious - more like Kafka's The Castle than Nineteen Eighty-Four. The dictator’s politics are hardly fleshed out; nor are those of the resistance that Stead's anti-hero unhappily joins. Stead is interested in telling a parable about the imperfection of humanity and the near-inevitability of the abuse of political power, not in comprehending the specifics of Kiwi society.Back to the future - again. I guess the reason that Stead's novel impacted so much more on popular consciousness is mainly because of those scenes in the film where faceless cops with batons beat the shit out of unarmed demonstrators. "When the Red Squad charged the anti-tour protestors in 1981, people said: 'It's just like Sleeping Dogs,'" said Sam Neill in his account of the film in his 1995 documentary Cinema of Unease.

Broken October, on the other hand, comes with an extended pre-history and a densely sociological present; it is a biggish novel stuffed with faux-newspaper reports and sardonic analyses of the policies of a US-backed military dictator and his trade unionist and Maori nationalist opponents. Stead's book could have been set anywhere, and written anytime in the twentieth century; Harrison's book could only have been written in New Zealand in the 1970s, a time when a strike wave, paranoia about communism, rising racial tension, and a nosediving economy were playing havoc with cosy myths about 'God's own country'.

Scott certainly has a point is in stressing Harrison's prescience in linking this political turmoil directly with race:

Warren Montag has argued that, in treating Heart of Darkness as an allegory for the human condition - that is, an abstract, ahistorical novel - literary canon-builders effectively diverted attention from Conrad’s expose of the horrors of colonialism in nineteenth century Africa. I think that some of the same tendency is at work when literary critics and historians choose Smith’s Dream over Broken October. Harrison is asking us to examine truths about Kiwi society which are concrete and uncomfortable. Stead lets us cop out by sermonising about a universal will to dictatorship. ('Nothing to do with the Maoris, mate, see.')'No politics in sport,' said the establishment spokespeople all through the closest thing New Zealand came to a civil war in 50 years - since the 1951 watersiders strike, in fact - the Springbok tour protests of 1981.

But, once again, it was all about race. Harrison, an outsider to the country, saw that obvious point at once, and has used it as the central vehicle for virtually all of his writing from this distant frontier. Stead's novel is, finally, a far more human piece of work than Harrison's, but its attempts to assert an apolitical common ground between the warring parties - seen most clearly, perhaps, in the famous closing vignette of the sunbathing girl - soon ceased to satisfy even himself. He rewrote that ending for the second edition, and it was rewritten again for Roger Donaldson's film.

Books that lose all interest once their topicality is past can never have been particularly good books in the first place. In fact, it's one of the few criteria we can apply to that perennial question: What actually makes a book good? What makes it worth reading?

Smith's Dream and Broken October are both still worth reading, imho. The first may be a better novel in terms of construction and plot, but the second certainly offers a richer and more nuanced vision of what was then the future - now, I suppose, an alternate timeline. Both, I think it's fair to say, played some small share in preventing the futures they foresaw from happening quite as described.

As I watch the land protests at Ihumātao, so reminiscent of Bastion Point in 1977 - the year after Harrison's novel appeared - the kind of dispute we were told need never happen again in the era of the Waitangi Tribunal, set up specifically to prevent such abuses from remaining unaddressed, I find myself wondering just how far we actually have got.

Walter Benjamin's Angel of History keeps on being swept backwards into the future, lamenting - but powerless to alter - the catastrophes happening in front of its face.

Select Bibliography:

- Books:

- How to be a Pom. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press, 1975.

- Broken October: New Zealand 1985. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed, 1976.

- The Quiet Earth. Auckland: Hodder and Stoughton, 1981.

- The Quiet Earth. 1981. Introduction by Bernard Beckett. Text Classics. Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company, 2013.

- Ground Level. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press, 1981.

- Days of Starlight. Auckland: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988.

- Grievous Bodily. Auckland: Penguin, 1991.

- The Essence of Art: Victorian Advice on the Practice of Painting. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 1999.

- The Dumpster Saga. Auckland: Scholastic New Zealand Limited, 2007.

- Ground Level. Wellington: Radio NZ, 1974.

- The Whites of their Eyes. Wellington: Radio NZ, 1974.

- Tomorrow Will Be a Lovely Day. Reed Drama Series. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed, 1975.

- Joe and Koro. Wellington: NZBC, 1976-77.

- The Quiet Earth. 1986.

- White Lies. Auckland: New House, 1994.

- The Quiet Earth, dir. Geoff Murphy, writ. Bill Baer, Bruno Lawrence, Sam Pillsbury (based on the novel by Craig Harrison) – with Bruno Lawrence, Alison Routledge, Pete Smith – (NZ, 1985).

- NZ Book council profile

- NZ on screen profile

- Wikipedia entry

Plays:

Screen Adaptations:

Homepages & Online Information: