Jo Elwyn Jones & J. Francis Gladstone. The Red King's Dream: Or Lewis Carroll in Wonderland. 1995. Pimlico 230. London: Random House, 1996.

The other day I was in Dominion Books, a little second-hand shop on Jervois Rd which has provided me with numerous treasures over the years, when I came across the book pictured above.

The authors' thesis (I haven't finished reading it yet) appears to be that Lewis Carroll's two Alice books contain a complex web of references to the contemporary culture, politics and religion of Victorian England - not in itself a particularly contentious claim, but one which they feel convinced offers a genuine key to the books' oddities and private in-jokes.

Funnily enough, a couple of weeks earlier I'd picked up a copy of that terrifyingly inclusive classic of political biography, Morley's Life of Gladstone:

John Morley. The Life of William Ewart Gladstone: In Two Volumes: Vol. I: 1809-1872. 1903. Lloyd's Popular Edition. London: Edward Lloyd, Limited, 1908.

John Morley. The Life of William Ewart Gladstone: In Two Volumes: Vol. II: 1872-1898. 1903. Lloyd's Popular Edition. London: Edward Lloyd, Limited, 1908.

One of the two authors of The Red King's Dream is actually Gladstone's great-grandson, and their book takes its departure in a very probable reference to Gladstone in the section of Through the Looking Glass devoted to the 'Lion and the Unicorn' (pictured by Tenniel as, respectively, Gladstone and Disraeli).

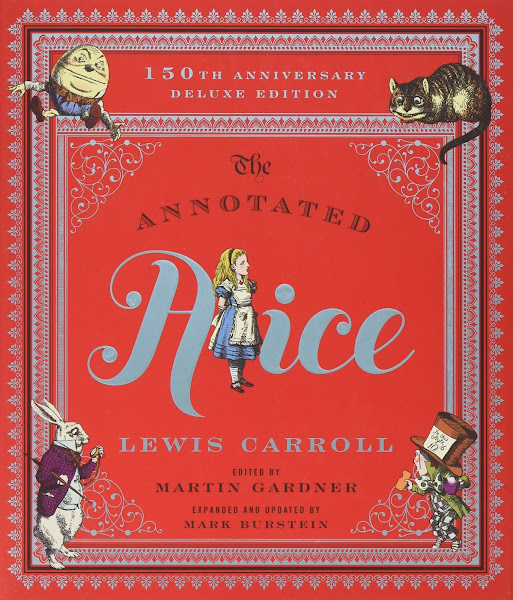

Much of the book is less convincing, and it certainly owes a heavy debt to the maniacally detailed researches of Martin Gardner, editor of three successive annotated versions of the Alice Books, culminating in the (posthumous) "150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition" of 2015:

Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass. Illustrated by John Tenniel. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Martin Gardner. Bramhall House. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1960.

Lewis Carroll. More Annotated Alice: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass. 1865 & 1871. Illustrated by Peter Newell. Ed. Martin Gardner. New York: Random House, 1990.

Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Ed. Martin Gardner. Illustrations by John Tenniel. 1960 & 1990. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 1999.

Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Ed. Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein. Illustrations by John Tenniel. 1960, 1990 & 1999. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2015.

However, it got me to thinking about just how many hare-brained books (and films) I've seen which claim to 'explain' these strange little books - some amusingly and tongue-in-cheek, others with ponderous earnestness. Quite apart from the intrinsic merits of the 'Alice' books themselves - my parents read them aloud to me even before I could follow print myself - I have to say that I think there are some genuine masterpieces among them.

Chief among these (after the Gardner book in its various manifestations) would have to be Bryan Talbot's extraordinary phantasmagoria in the form of a graphic novel Alice in Sunderland:

Bryan Talbot. Alice in Sunderland: An Entertainment. Jonathan Cape. London: Random House Group Limited, 2007.

Talbot, a graphic virtuoso, one of whose previous books, The Tale of One Bad Rat, was composed almost entirely in the style of Beatrix Potter, really pulls the stops out for this, his masterpiece:

Bryan Talbot. The Tale of One Bad Rat. 1994-5. Jonathan Cape. London: Random House Group Limited, 2008.

His bizarre script doubles as a potted history of Sunderland, a social history of Victorian England, and a penetrating analysis of Alice itself - both as a biographical and an aesthetic document. Along the way we encounter such local characters as George Formby, Sid James, and the Lambton Worm, as well as the more obvious Charles Dodgson, Alice Liddell and John Tenniel. It has really to be read to be believed:

Here are a few extracts to give you an idea of the kinds of connections he specialises in:

To continue with the theme of graphic novels, Lewis Carroll's favourite muse, Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (née Liddell), also makes an extended appearance in Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie's weird semi-pornographic extravaganza Lost Girls, alongside Dorothy Gale, from L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), and Wendy Darling, from J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan (1904).

Alan Moore. Lost Girls. Illustrated by Melinda Gebbie. 3 vols. Marietta, Georgia: Top Shelf Productions, 2006.

As Wikipedia puts it, in its characteristically po-faced fashion:

They meet as adults in 1913 and describe and share some of their erotic adventures with each other.The book culminates with the eruption of the First World War in 1914. Here's a medley of the original covers for the 3-volume slipcase edition to give you the general idea:

Like all of Alan Moore's books, this one is both intricately plotted and technically ingenious. Beyond that, though, it's hard to see as much substance in it as in Talbot's almost exactly contemporaneous non-fiction novel.

Which brings us to films. The Alice books have a varied - and, for the most part, indifferent - filmography. They've had to endure a poor Disney animation, and two weird Tim Burton adaptations. There are, however, some high points here and there.

Alice in Wonderland, dir. & writ. Jonathan Miller (from the book by Lewis Carroll) – with Anne-Marie Mallik, John Gielgud, Peter Cook, Leo McKern, Peter Sellers – (UK, 1966).

The first of these is Jonathan Miller's trippy BBC TV adaptation. It may be low on budget, but it's big on ideas and disturbing images. The 13-year-old unknown, Anne-Marie Mallik, who plays the main character is disturbingly sensual in her impersonation (or enactment) of a mid-60s flower child.

The central metaphor (it was mostly filmed in an old 19th century hospital) is of Victorian England as a madhouse full of cracked, elderly monologists, expertly impersonated by the principal comedians of the time. Its application to contemporary conditions in that embattled island remains rather current, unfortunately.

Dreamchild, dir. Gavin Millar, writ. Dennis Potter – with Coral Browne, Ian Holm, Peter Gallagher, Nicola Cowper, Amelia Shankley – (UK, 1985).

Dreamchild, at the time, attracted most attention as a showcase for the admittedly impressive animating skills of Jim Henson and his Creature Shop. The central (truish) story of an elderly Mrs. Hargreaves - Lewis Carroll's original Alice - sailing to New York to receive an Honorary Doctorate from Columbia University is somewhat marred by a mawkish love story.

However, the intercut scenes of her younger self in and out of Carroll's dreamscapes are beautifully done, with pitch-perfect performances from both Ian Holm as Carroll/Dodgson/the Dodo and Amelia Shankley as a mischievously flirtatious young Alice.

Alice [Něco z Alenky], dir. & writ. Jan Švankmajer (from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) - with Kristýna Kohoutová - (Czechosolvakia, 1988).

Last but not least is this piece of weirdness from the great Czech film-maker Jan Švankmajer. His film (whose title translates as 'Something from Alice') combines the cracked genius of his stop-motion animation skills with the darkness of his Freudian vision of a world of broken-down dolls and malevolent animals.

While it's not precisely fun to watch, it proves once again the seemingly inexhaustible power of the Alice books as a reservoir of imagery for our troubled modernity.

It was, I think, W. H. Auden who remarked of Alice herself:

In Wonderland, she is the only person with self-control.We continue to foist our visions - social or sexual, literary or psychological, mathematical or historical, eccentric or universal - upon her. She remains, however, unreachable, untouchable, immaculate - like Thurber's Walter Mitty, 'inscrutable to the last.'

•

Charles Dodgson: Alice Pleasance Liddell as a beggar girl (1858)

Gallery:

A Baker's Dozen of Alices

(1858-?)

- Lewis Carroll. The Complete Works: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; The Hunting of the Snark; Through the Looking Glass; Sylvie and Bruno; Sylvie and Bruno Concluded; All the Early and Late Verse, Short Stories, Essays, Phantasmagoria. Games, Puzzles, Problems, Acrostics, and Miscellaneous Writings . Illustrated by John Tenniel. Introduction by Alexander Woollcott. 1939. Modern Library Giant. New York: The Modern Library, n.d.

- Roger Lancelyn Green, ed. The Works of Lewis Carroll. Illustrations by John Tenniel. Spring Books. London: Paul Hamlyn Ltd., 1965.

- Roy Gasson, ed. The Illustrated Lewis Carroll: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There; The Hunting of the Snark; A Carroll Selection; Appendix: The "Alice Verses" and their Originals. 1978. Poole, Dorset: New Orchard Editions Ltd., n.d.

- Edward Giuliano, ed. The Complete Illustrated Works of Lewis Carroll: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There; The Hunting of the Snark; Rhyme? and Reason?; A Tangled Tale; Alice’s Adventures Underground; Sylvie and Bruno; Sylvie and Bruno Concluded; Three Sunsets and Other Poems. Illustrated by John Tenniel, Lewis Carroll, Arthur B. Frost, Henry Holiday, Harry Furniss, & E. Gertrude Thomson. Avenel Books. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1982.

- Alice’s Adventures Underground: Facsimile of the Author’s Manuscript Book with Additional Material from the Facsimile Edition of 1886. Introduction by Martin Gardner. New York: Dover Publications. Inc., 1965.

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There. Illustrated by John Tenniel. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Roger Lancelyn Green. 1971. Oxford English Novels. London: Book Club Associates, 1976.

- Alice in Wonderland: Authoritative Texts of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; Through the Looking-Glass; The Hunting of the Snark. Backgrounds, Essays in Criticism. Ed. Donald J. Gray. A Norton Critical Edition. New York: W. W. Norton, 1971.

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Introduction by Langford Reed. Illustrated by Helen Monro. Nelson Classics. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., n.d.

- Alice Through the Looking-Glass. Illustrated by Maraja. London: W. H. Allen, 1959.

- The Wasp in a Wig: A "Suppressed" Episode of Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There. Preface, Introduction & Notes by Martin Gardner. Ed. Edward Giuliano. 1977. London: Macmillan Limited, 1977.

- Carroll, Lewis. The Annotated Snark: The Hunting of the Snark – An Agony in Eight Fits. Illustrations by Henry Holiday. 1876. Ed. Martin Gardner. 1962. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

- Carroll, Lewis. The Humorous Verse of Lewis Carroll. [Formerly: 'The Collected Verse of Lewis Carroll']. With illustrations by Sir John Tenniel, Arthur B. Frost, Henry Holiday, Harry Furniss, & the Author. 1933. New York: Dover Publications. Inc., 1960.

- Charles L. Dodgson, M.A. Euclid and His Modern Rivals. 1879. Introduction by H. S. M. Coxeter. New York: Dover Publications. Inc., 1973.

- Symbolic Logic and The Game of Logic (Both Books Bound as One): Mathematical Recreations of Lewis Carroll. 1897 & 1887. Preface by Edmund C. Berkeley. New York: Dover Publications. Inc. / Berkeley Enterprises, 1958.

- Carroll, Lewis. Diversions and Digressions of Lewis Carroll (Formerly Titled: The Lewis Carroll Picture Book): A Selection from the Unpublished Writings and Drawings of Lewis Carroll, together with Reprints from Scarce and Unacknowledged Work. With a New Selection of Lewis Carroll’s Photographs. Ed. Stuart Dodgson Collingwood. 1899. New York: Dover Publications. Inc., 1961.

- Carroll, Lewis. The Story of Sylvie and Bruno. Ed. Edwin Dodgson. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 1904. Facsimile Classics Series. New York: Mayflower Books. Inc. / London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1980.

- Carroll, Lewis. The Rectory Umbrella and Mischmasch. Foreword by Florence Milner. 1932. New York: Dover Publications. Inc., 1971.

- Fisher, John, ed. The Magic of Lewis Carroll. Line Illustrations by Sir John Tenniel, Henry Holiday, Arthur B. Frost, Harry Furniss, & Lewis Carroll. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973.

- Ovenden, Graham. Masters of Photography: Lewis Carroll. London: Macdonald & Co (Publishers) Ltd., 1984.

- Cohen, Morton N., with Roger Lancelyn Green, ed. The Letters of Lewis Carroll. Vol. I: ca.1837-1885. Vol. 1 of 2. London: Macmillan London Limited., 1979.

- Cohen, Morton N., with Roger Lancelyn Green, ed. The Letters of Lewis Carroll. Vol. II: 1885-1898. Vol. 2 of 2. London: Macmillan London Limited., 1979.

- Cohen, Morton N., with Roger Lancelyn Green, ed. The Selected Letters of Lewis Carroll. 1979. Papermac. London: Macmillan Publishers Limited., 1982.

- McDermott, John Francis, ed. The Russian Journal and Other Selections from the Works of Lewis Carroll. 1935. New York: Dover Publications. Inc., 1977.

- Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll (Rev. C. L. Dodgson). 1898. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, n.d.

- Lennon, Florence Becker. The Life of Lewis Carroll [aka 'Victoria through the Looking-Glass']. 1945. Rev. ed. Collier Books. New York: The Crowell-Collier Publishing Company, 1962.

- Gordon, Colin. Beyond the Looking Glass: Reflections of Alice and Her Family. San Diego & New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1982.

- Cohen, Morton N. Lewis Carroll: A Biography. 1995. Vintage Books. New York: Random House Inc., 1996.

- Huxley, Francis. The Raven and the Writing Desk. London: Thames & Hudson, 1976.

- Phillips, Robert, ed. Aspects of Alice: Lewis Carroll’s Dreamchild as seen through the Critics’ Looking-Glasses, 1865-1971. 1971. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

- Sigler, Carolyn, ed. Alternative Alices: Visions and Revisions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books. An Anthology. Lexington, Kentucky: Kentucky University Press, 1997.

Collected Works:

Editions of 'Alice':

Poetry:

Mathematics & Logic:

Miscellaneous:

Diaries & Letters:

Biographical:

Literary Critical: