For though my ryme be ragged,I think I first encountered John Skelton via a side-reference in Siegfried Sassoon's Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930), his fictionalised account of life on the Western Front in the First World War. Sassoon describes his fellow-officer 'David Cromlech' [= Robert Graves] as follows:

Tattered and jagged,

Rudely rayne beaten,

Rusty and moughte eaten,

It hath in it some pyth.

He made short work of most books which I had hitherto venerated, for David was a person who consumed his enthusiasms quickly, and he once fairly took my breath away by pooh-poohing Paradise Lost as ‘that moribund academic concoction’. I hadn’t realized that it was possible to speak disrespectfully about Milton. Anyhow, John Milton was consigned to perdition, and John Skelton was put forward as ‘one of the few really good poets.’ But somehow I could never quite accept his supremacy over Milton as an established fact.John Skelton? Who he? My passionate interest in any and everything to do with Robert Graves soon led me to the latter's early poem "John Skelton", included in the wartime collection Fairies and Fusiliers (1917) but not reprinted in any of the various editions of his Collected Poems:

... angrily, wittily,I was therefore immensely excited to find an old edition of the Shakespearean scholar Alexander Dyce's 19th century edition of Skelton in a second-hand shop sometime in the 1970s. Unfortunately, it was only the first of two volumes, but it contained all the text - though without any of Dyce's detailed explanatory notes.

Tenderly, prettily,

Laughingly, learnedly,

Sadly, madly,

Helter-skelter John

Rhymes serenely on,

As English poets should.

Old John, you do me good!

But who was this man John Skelton, anyway?

Probably his principal claim to fame in the eyes of posterity is the fact that he acted as Henry VIII's tutor in the late 1490s, and wrote a book of advice (now lost) for the young prince in the genre generally classified as Speculum Principis [Mirror for Princes].

He was immensely proud of having been crowned as a "laureate" at Oxford university, and subsequently at Cambridge, then Leuven in Flanders. The term didn't mean then what it does now, though. It signified high attainment in rhetoric, rather than official appointment as a court poet.

Even so, Skelton wrote an outrageously exaggerated poem called The Garland of Laurel to celebrate this event, deliberately blurring its significance in order to milk the maximum mileage out of the distinction. He also signed himself 'Skelton, Laureat' ever afterwards.

After a brief period of imprisonment for unknown reasons in the early 1500s, Skelton retired from regular attendance at court, composing another long poem entitled The Bowge of Court to satirise the terrible corruption and greed he found there under the (so-called) Accountant King, Henry VII.

Instead, he took up the role of rector of Diss in Norfolk, where he is said to have caused a good deal of scandal with his unorthodox behaviour and views:

his parishioners ... thought him more fit for the stage than the pew or the pulpit. He was secretly married to a woman who lived in his house, and earned the hatred of the Dominican friars by his fierce satire. He consequently came under the formal censure of Richard Nix, the bishop of the diocese, and appears to have been temporarily suspended. After his death a collection of farcical tales, no doubt chiefly, if not entirely, apocryphal, gathered round his name — The Merie Tales of Skelton.- Wikipedia: John Skelton

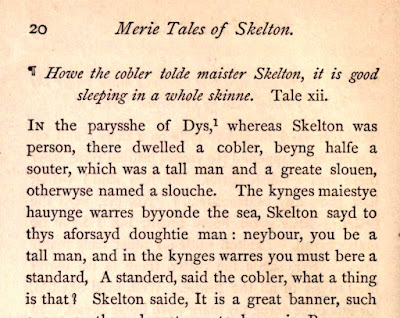

One of the most valuable features of Dyce's edition of Skelton is the inclusion, in an appendix, of the entire text of this ridiculous book of fifteenth-century 'humour'. Most of the gags tend to hinge on someone being beaten within an inch of their lives, or otherwise bested by the arch-joker Skelton. The extract below will give you some idea of the kind of thing it is:

So what was it that Graves, and others, saw in this rather absurd sounding figure? Well, for a start, between the death of Geoffrey Chaucer in 1400 and the introduction of Italianate verse forms such as the sonnet into England in the 1530s and 40s by Sir Thomas Wyatt and the Earl of Surrey, there isn't really a lot to celebrate in English poetry.

Most of the serious action was taking place north of the border in Scotland, where poets such as Gavin Douglas, William Dunbar, and Robert Henryson were continuing - and extending - the tradition of Chaucerian narrative verse.

And what did England have to offer in response? Well, there's Skelton's poem 'Against the Scots,' his sensitive account of the tragic Battle of Flodden:

Lo, these fond sotsIt puts one rather in mind of Tennyson's 'Charge of the Light Brigade', doesn't it?

And trattling Scots,

How they are blind

In their own mind,

And will not know

Their overthrow

At Brankston Moor!

They are so stour,

So frantic mad,

They say they had

And won the field

With spear and shield:

That is as true

As black is blue

And green is grey.

Whatever they say,

Jemmy is dead

And closed in lead,

That was their own king:

Fie on that winning!

That's probably the least attractive aspect of Skelton. He did have a gift for lyric verse, though, witness the portraits of court ladies included in his Garland of Laurel:

Merry Margaret,You can certainly see his influence not just on Robert Graves, but also on other early twentieth-century poets such as Edith Sitwell and W. H. Auden.

As midsummer flower,

Gentle as a falcon

Or hawk of the tower:

With solace and gladness,

Much mirth and no madness,

All good and no badness;

So joyously,

So maidenly,

So womanly

Her demeaning

In every thing,

Far, far passing

That I can indite,

Or suffice to write

Of Merry Margaret

As midsummer flower,

Gentle as falcon

Or hawk of the tower.

As patient and still

And as full of good will

As fair Isaphill,

Coriander,

Sweet pomander,

Good Cassander,

Steadfast of thought,

Well made, well wrought,

Far may be sought

Ere that ye can find

So courteous, so kind

As Merry Margaret,

This midsummer flower,

Gentle as falcon

Or hawk of the tower.

Here's the former's 'Aubade', included in some versions of her 'instrumental entertainment' Façade (1923):

Jane, Jane,Comb your cockscomb-ragged hair,

Tall as a crane,

The morning light creaks down again;

Jane, Jane, come down the stair.

Each dull blunt wooden stalactite

Of rain creaks, hardened by the light,

Sounding like an overtone

From some lonely world unknown.

But the creaking empty light

Will never harden into sight,

Will never penetrate your brain

With overtones like the blunt rain.

The light would show (if it could harden)

Eternities of kitchen garden,

Cockscomb flowers that none will pluck,

And wooden flowers that 'gin to cluck.

In the kitchen you must light

Flames as staring, red and white,

As carrots or as turnips shining

Where the cold dawn light lies whining.

Cockscomb hair on the cold wind

Hangs limp, turns the milk's weak mind . . .Jane, Jane,

Tall as a crane,

The morning light creaks down again!

And here's the latter's 1930 poem 'This Lunar Beauty':

This lunar beauty

Has no history

Is complete and early,

If beauty later

Bear any feature

It had a lover

And is another.

This like a dream

Keeps other time

And daytime is

The loss of this,

For time is inches

And the heart's changes

Where ghost has haunted

Lost and wanted.

But this was never

A ghost's endeavor

Nor finished this,

Was ghost at ease,

And till it pass

Love shall not near

The sweetness here

Nor sorrow take

His endless look.

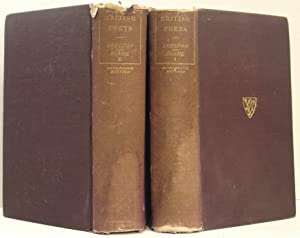

So how to sum up the longterm influence of John Skelton? The lack of a readily available modern edition of his poems - or the ones in English, at any rate - was addressed, first, by Philip Henderson's frequently reprinted Dent edition of 1931.

Some of the textual deficiencies in Henderson's version have now been corrected by Skelton-biographer John Scattergood's Complete English Poems (1983) in the Penguin English Poets series.

Is he worth reading? A lot of his work is, admittedly, probably only of interest to medievalists and literary scholars, but there's a good deal of vivid satire and storytelling there which does go some way towards justifying Robert Graves' favourable verdict.

For the rest, I should probably leave you with probably the most celebrated of those 'Merie Tales of Skelton' which at least did something to carry his name down to posterity:

Tale vii:So there you go. It is indeed merry in the hall, when beards wag all.

How Skelton, when he came from the bishop, made a sermon.

Skelton the next Sunday after went into the pulpit to preach, and said, "Vos estis, vos estis, that is to say, You be, you be. And what be you?" said Skelton: "I say, that you be a sort of knaves, yea, and a man might say worse than knaves; and why, I shall show you. You have complained of me to the bishop that I do keep a fair wench in my house: I do tell you, if you had any fair wives, it were some what to help me at need; I am a man as you be: you have foul wives, and I have a fair wench, of the which I have begotten a fair boy, as I do think, and as you all shall see. Thou wife," said Skelton, "that hast my child, be not afraid; bring me hither my child to me:" the which was done. And he, showing his child naked to all the parish, said, "How say you, neighbours all? is not this child as fair as is the best of all yours? It hath nose, eyes, hands, and feet, as well as any of your: it is not like a pig, nor a calf, nor like no fowl nor no monstrous beast. If I had," said Skelton, "brought forth this child without arms or legs, or that it were deformed, being a monstrous thing, I would never have blamed you to have complained to the bishop of me; but to complain without a cause, I say, as I said before in my antetheme, vos estis, you be, and have be, and will and shall be knaves, to complain of me without a cause reasonable. For you be presumptuous, and do exalt yourselves, and therefore you shall be made low: as I shall show you a familiar example of a parish priest, the which did make a sermon in Rome. And he did take that for his antetheme, the which of late days is named a theme, and said, Qui se exaltat humiliabitur, et qui see humiliat exaltabitur, that is to say, he that doth exalt himself or doth extol himself shall be made meek, and he that doth humble himself or is meek, shall be exalted, extolled, or elevated, or sublimated, or such like; and that I will show you by this my cap. This cap was first my hood, when that I was student in Jucalico, and then it was so proud that it would not be contented, but it would slip and fall from my shoulders. I perceiving this that he was proud, what then did I? shortly to conclude, I did make of him a pair of breeches to my hose, to bring him low. And when that I did see, know, or perceive that he was in that case, and allmost worn clean out, what did I then to extol him up again? you all may see that this my cap was made of it that was my breeches. Therefore, said Skelton, vos estis, therefore you be, as I did say before: if that you exalt yourself, and cannot be contented that I have my wench still, some of you shall wear horns; and therefore vos estis: and so farewell." It is merry in the hall, when beards wag all.

- The Poetical Works of Skelton and Donne with a Memoir of Each. Ed. Alexander Dyce. 1843. 4 Vols in 2. Riverside Edition. 1855. Cambridge: The Riverside Press / Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1881.

- Skelton, John. The Complete Poems of John Skelton, Laureate: 1460-1529. Ed. Philip Henderson. 1931. Everyman’s Library. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. / New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1966.

- Skelton, John. The Complete English Poems. Ed. John Scattergood. Penguin English Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- Pollet, Maurice. John Skelton: Poet of Tudor England. 1962. Trans. John Warrington. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1970.

•