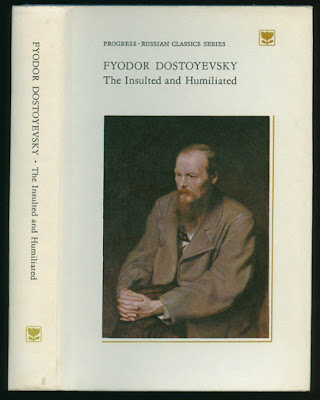

A lot of people have used that title -

The Mysteries of ... [somewhere or other] - since Ann Radcliffe first dreamed it up in 1794. She may have been laughed off stage by Jane Austen in her early novel

Northanger Abbey, but Radcliffe's Gothic cliffhangers remain surprisingly readable:

The most famous example of this would have to be Eugène Sue's phenomenally successful serial

Les Mystères de Paris, which - when eventually collected in book-form - ran to over a thousand pages of blood-and-thunder romance:

Eugène Sue's book also gave rise to the (so-called) "

city mysteries" fictional subgenre, which eventually included:

- George W. M. Reynolds' The Mysteries of London (1844)

- Paul Féval's Les Mystères de Londres (1844)

- August Brass's Die Mysterien von Berlin (1844)

- L. van Eikenhorst's De Verborgenheden van Amsterdam (1844)

- Johann Wilhelm Christern's Die Geheimnisse von Hamburg (1845)

- Ned Buntline's The Mysteries and Miseries of New York (1848)

- Camilo Castelo Branco's Os Mistérios de Lisboa (1854)

- Émile Zola's Les Mystères de Marseille (1867)

- Francesco Mastriani's I misteri di Napoli (1869-70)

and many, many others - culminating in Michael Chabon's affectionate

hommage to the form,

The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (1988).

But how does all this connect up with Ashburton, the ostensible subject of this post? Besides that extraordinary shot of the Ashburton Post Office above, there are many other reasons for finding Ashburton a strangely interesting place.

•

Or so we thought, at any rate, when we arranged to spend some time there earlier this month:

HEARTLAND HOUSE

[unless otherwise attributed, the photos in this post are by Bronwyn Lloyd (7/1/19)]

HEARTLAND HOUSE

[unless otherwise attributed, the photos in this post are by Bronwyn Lloyd (7/1/19)]

What on earth is

this extraordinary structure, for instance? A piece of monumental art? A public convenience? It certainly serves to mark off very emphatically the railway lines which run straight through the centre of town from the rest of the Ashburton CBD.

The rails run south-west

The rails run south-west

The rails run north-east

The rails run north-east

they're echoed by these curious ley-lines on the nearby domain

they're echoed by these curious ley-lines on the nearby domain

which led us to a grove of trees

which led us to a grove of trees

with some stones to one side

with some stones to one side

disfigured by graffiti

disfigured by graffiti

Does the inscription read "

f O R e s t"? Or could it be "

f [infinity sign] r s t"? It's hard to tell. The first would certainly make the most sense, but that sideways eight does seem visible, also.

stone "Z" (or "V")

stone "Z" (or "V")

The stones, too, are in the shape of a symbol of some kind: perhaps an arrowhead? Is it pointing somewhere? Or is it indeed that "

X marks the spot"?

musing on the connections

musing on the connections

•

Unimpressive, you think? You were expecting a little more? Wait, there's more ...

The idea of a grove of trees labelled "forest" reminds me a little of the moment in Janet Frame's late novel

Living in the Maniototo when one of her characters, obsessed with the idea of taking a long journey through the desert, decides to undertake a short test-run near Berkeley, California. The other members of the group "deposit Roger beneath a road-sign marked ‘DESERT’." One of them comments:

it doesn’t seem real. In a country like the USA where public information is intimate and discursive, you don’t see abrupt signs like that! [171]

As Matt Harris unpacks the scene in his 2012 Doctoral thesis,

Metafiction in New Zealand from the 1960s to the present day:

The sign is less designating a geographical region than it is a linguistic marking of the boundary between reality and the quixotic imagination. This is the ‘DESERT’, but not the desert Roger had idealised. ... Although he is certain that he will experience an epiphany, if not on this simulated journey then on a later journey across one of the great deserts, no such revelation is forthcoming and he begins to “feel irritated with himself for his engrossing concern for the “real” desert, the “real” journey so vivid in his mind …” [175] Perhaps unsurprisingly, Roger decides at the end of his sojourn that the real journey might not be necessary. “Why indeed go into a “real”, “utter” desert?” he asks himself. “It was in trying to test the reality that one met all the problems and failures, not only of the thing itself but of the mind that is occupied obsessively with dualism.” [185]

•

So what's so significant about Ashburton? What brings in visitors - besides those who simply stop in briefly on their way down the Coast Road from Christchurch to Dunedin? The main things

Trip Advisor can find to mention are: the Ashburton Domain (pictured above), the

Ashburton Art Gallery (which had on, during our stay, an intriguing exhibition called

Snark: A Victorian Odyssey, inspired by Lewis Carroll's famous poem); The Plains Vintage Railway & Historical Museum; skydiving; and trout-fishing.

As well as all these, I'd add the fact that there's a rather marvellous bookshop just a few kilometres out of town:

Chertsey Book Barn (7/1/19)

Chertsey Book Barn (7/1/19)

What I

didn't find in there, though, despite an extensive search, was a copy of Ashburton's principal literary claim to fame: the pioneering science fiction novel entitled

The Great Romance (1881), published pseudonymously by someone describing himself simply as "The Inhabitant", and printed on the presses of the local newspaper.

And, yes, it was that which drew me to Ashburton. Not that I expected to pick up any real clues about the identity of its author, or even - really - to flesh out any of its narrative details with local colour, but really just to get a sense of the place: 138 years later, admittedly, but sometimes you can catch a lucky break on these little expeditions.

•

Here are some extracts from "The Inhabitant"'s account of his heroes - Weir, Moxton and Hope's - approach to the planet Venus in their space ship

Star Climber:

The poles of the planet Venus are at such an angle that about half the planet enjoys alternately a day of three months — a long dim day of twilight, and then night; as a natural consequence, the regions approaching this country are strangely affected. When we woke in the morning we saw the first proof of this in the low sun, still hanging at the same altitude, the live-long night he had been thus creeping around, so that here there was no day or night, morning or evening, and the waste of desert around us seemed as if made for these monotonous periods.

We spread out the wings of our vessel and went on our way ... We had determined to go right over the pole of the planet, but, as we did not like to shut ourselves up again, we were soon obliged by the rarified air to turn to the lower and warmer regions, going away swiftly till grass and wood and water again began to reign, then sailing slowly, and not too high, that we might observe if anything like humanity should appear — we saw troops of beasts, four-legged and two-legged—ape-like creatures — kangaroo, or more properly three-legged animals; but none of them seemed struck with wonder as we glided slowly above them — they all fed and played and fought, as though there were nothing new under their Heaven, and if we swept down near them went away with screams and cries to their shelters. Their forms were very strange — ever recalling something we knew, yet always differing from it; yet what we most noticed — what seemed to be an unvarying characteristic — was that, whether large or small, they all moved in troops and bands, all fed and fought together, and all seemed well provided for either attack or defense; but nothing human appeared, nought of a nature similar to our own.

I can hardly tell how much we wished — how our hearts would have gone out towards any living creature which should have risen above the level of the animal world, or how out thoughts wondered over the intellectual union which might arise, should two such experiences join their pleasures, their results; yet here there was enough to recall the wildest wandering thoughts, as we went hither and thither to and from every new object, everything that promised a revelation, over lakes and mountains, rivers and forests, till we felt ourselves in the tropical regions, with the high sun blazing overhead, and the great bush herbage, and vast trees all about us.

Is it just me, or is there a certain sense of the Antipodes of our own planet in these descriptions? The kangaroos, and the 'great bush herbage, and vast trees all around us'?

Presumably, given the date of his story, this "inhabitant" must have been an immigrant to New Zealand, and his voyage from the cities of the future described in the first section of his novel, to these more verdant regions, does sound like lived experience, however much he's tried to mask the fact with these interplanetary trimmings.

Yet none of this would please Moxton, he would press on to the winter half of the planet, to the land of shadow, and we expected of ice and snow, for warm as the planet was, we thought that three months' exclusion from the sun's heat, would bring the temperature very low. Yet we could not help lingering, turning to each new beauty of flower and fruit, leaf, or herbage, skimming near the edge of the forest, or the waters of the rivers, hoping to see some new elephant or huge mastodon ... So we were borne steadily onward through the fresh air of the new world — were always eager to behold something fresh — unsatisfied with the wonders of Heaven — we seemed to forget the leagues that we had travelled, unmindful of our great fate, to run like older babes in the wood from flower to flower as fancy guided us.

Yet stopping often as we did, our immense speed led us fast from clime to clime, and before the natural day would decline the sun began to grow low on the northern horizon; the tropical forests to be replaced by grassy plains and rolling, scantily timbered hills. Sometimes, too, we came on arid sand — huge dry deserts without even the proverbial vulture to enliven them; then succeeded strange twilight, with the sun low down, and its beams striking along the world — the air seemed to grow vague and yellow, a thickness and foggyness pervaded everything. How changed seemed the vegetation — rotting leaves and bare boughs; huge stalked grass, half-decayed — and here, too, we saw more birds, great downy owls, and bats to which the devil of the middle ages was a mild creature, it also seemed the land of frogs and toads — huge speckled tawny creatures, not good to look at; and the vegetation altered fast now, the reign of the fungus seemed to have begun — the ground, the trees, the water, were covered with minute forms, and in the opener spaces huge growths stranger than the cactus or fungus of the world, immense groups of all shapes, so strange were they, that even Moxton agreed to come to a stand for a while.

Lake Heron, North Canterbury

Lake Heron, North Canterbury

After they land, it is agreed that Weir and Moxton will continue their explorations in

Star Climber, while John Bentford Hope stays behind on the surface of Venus. The place they choose to leave him in is described as follows:

We had selected a spot some hundreds of feet above the common level, for here all the water seemed land-locked, standing like inland lakes at all sorts of heights, rising and falling, with the season, and with no general inter-communication. It was a fine sweeping plain within the tropics, but kept cool by its elevation, and by the fact that on the still higher ground spread a large lake. There were a few trees scattered here and there, sometimes in clumps, and under a near group I had a large tent fixed for comfort in the warmer weather. [64]

"There is no doubt we were fools," said Weir, "to arrange to leave you here. There [could be] many things on this planet of which we know nothing - even the beasts have almost sense enough to besiege you. If I were you I should not travel except in the air. You are quite safe in that little boat, and even when you are about here I would always keep a revolver in my hand - make a habit of it." [67]

As it turns out, though, Hope has no need to travel in order to find out more about the planet's inhabitants. Instead, they come calling on

him: a pair of aliens, with "intelligence, knowledge, in every line of their features, and with low, strange voices" [71-2]:

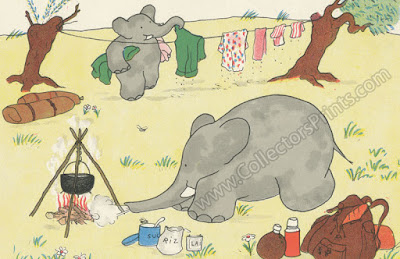

I woke to the sense of their presence, to seem them gazing down, arms linked to each other, male and female, gazing with soft eyes on my yet recumbent figure, their fine bodies covered with a down - neither of bird nor animal - soft and dark, and their heavy, lithe limbs, such as might have developed form the earliest of prehistoric elephant, had not the heat of a younger world debased him, and nature's giant youth pushed him in her recklessness to balk rather than serve. [71]

Judging from the description above, they sound a little like clones of

Babar the Elephant. It's hard not to humanise them in one's own imagination, though.

"Their little attentions to each other ... were so new and original, that I was occupied with but watching them. These were not savages, and how far removed from animals" [72]

"Their little attentions to each other ... were so new and original, that I was occupied with but watching them. These were not savages, and how far removed from animals" [72]

After they've visited with him for a bit, the two aliens - refusing his invitation to enter Hope's "castle" (as he calls it). Instead:

"They led me to the borders of the upland lake, and there under the tall herbage was a rude boat, or rather raft. They evidently wished me to embark with them, but to this I would not consent, and after a while they left me, promising, as far as signs could point, to return again." [73]

"They led me to the borders of the upland lake, and there under the tall herbage was a rude boat, or rather raft. They evidently wished me to embark with them, but to this I would not consent, and after a while they left me, promising, as far as signs could point, to return again." [73]

Instead, Hope himself fires up his airship, the

Midge ("she could run, or fly, or swim" [76]) and pursues them to the upland lake they'd rowed across the previous day.

"What should I call them? By what name should I think of them? ... then I thought of the star, the planet of love, and determined to call them by it, namely, Venus, and by that name they were afterwards known." [76]

"What should I call them? By what name should I think of them? ... then I thought of the star, the planet of love, and determined to call them by it, namely, Venus, and by that name they were afterwards known." [76]

The Venuses lead him trustingly back to their home, "a small mossy cabin, with a strange, bird-like air pervading it," where they appear to live all on their own:

But were they indeed so completely alone? I thought and asked, as I looked out again and could see no sign of other habitations ... and as I looked at their provisions I divined the reason - if they lived without tillage on the fruits of the ground, they must need be few in number, and live far apart. [77]

"Hope left the two Venuses still on the beach, and sailed out in his boat on the lake down the long winding-like water." [85]

"Hope left the two Venuses still on the beach, and sailed out in his boat on the lake down the long winding-like water." [85]

The idyll is broken by a sudden resurgence of the colonial mentality in Hope:

Yet, after all, it was they who had to learn. Their mind in its best phases had little that was superior to humanity. Some happier thoughts - some sweet companionship - some feelings of freedom and pleasure - new perhaps to any inhabitant of my native world; yet of that great body of thought which has arisen from our mechanical and omniverous [sic.] propensities, they knew nothing, and as I afterwards found out, were saved from stupidity and savageness by the long-continuing slowness of their mental emotions, and by their wonderful care of, and kindness to, each other. [77-78]

He promptly teaches them "the mystery of fire" and starts to plot their future subjugation. After all, he and his friends:

had come to find a future home for the growing millions of their native earth, and here all around the tropical zone was a region fitted with everything necessary, while the dim polar regions would serve to exercise all the latent ingenuity of the coming man. [88]

This rather chilling vision is exacerbated by the author's strange habit of switching from first person to third person narration in adjacent chapters. It's tempting to see in this a device for showing the divided nature of his protagonist, simultaneously attracted by and scornful of these gentle inhabitants of the new planet he is exploring. Certainly, at times, his thought processes are described in quite violent terms:

I laughed aloud as one in madness at what I knew not, except that all things jarred and frayed, and roughened all my spirit, and the Venuses sat on without turning a thought or eye towards me or my wild motions. [79]

The author's clumsiness of diction and general lack of narrative sophistication would seem to argue against this conclusion, but one would certainly have to acknowledge the intensely

experimental nature of this piece of proto-science fiction. It is as if he is literally trying to invent a new genre as he goes along.

Another interesting aspect of Hope's courting of the Venuses is that it is juxtaposed with chapters describing Weir and Moxton's explorations among the asteroids. This second volume of his work (which must surely have been

intended to have a sequel, even though no trace of it has ever been found) ends, in fact, on a literal cliffhanger, as Weir tumbles off the side of a planetoid, plummeting (as it turns out) forever:

Moxton saw him with arms wide-spread falling, falling and turning - good God! Would he never cease to fall? The huge rock fell and struck, and fell again - but Weir [...] out in space. Moxton thought his brain would burst. Would Weir never cease to fall? [102]

These are the last words of his story.

•

What then, is one to make of

The Great Romance? Contemporary critics were pretty harsh:

Review of The Great Romance. By the Inhabitant. Vols. I and II. Dunedin: Printed at the Daily Times Office. Otago Daily Times, Issue 5247 (18 February 1882): 1.

Review of The Great Romance. By the Inhabitant. Vols. I and II. Dunedin: Printed at the Daily Times Office. Otago Daily Times, Issue 5247 (18 February 1882): 1.

This is evidently the work of a young and unpractised writer. It is full of crudities of style and matter which lay it open to criticism on almost every page; but there is something about it a little out of the common way. It exhibits an exuberant fancy, and an adroitness in avoiding obvious difficulties, that redeem it from absolute inanity, though the absurdities of its plan and the impossibilities of its details render it a fair mark for ridicule. The two “volumes” are, in reality, only pamphlets; and, as there is yet more to come, we can only faintly guess what the whole will be. The interest is well sustained so far, and lovers of Jules Verne’s delightful voyages of discovery into the unknown will find amusement for an hour or two in “The Great Romance,” even as far as it has gone. The writer, who takes the name of J. R. [for ‘B’] Hope, goes to sleep in 1950 under the influence of a chemical sleeping-draught of wondrous potency, and wakes up in 2143 in another state of existence. Finding his old friends and his ladylove greatly sublimed and glorified, he is naturally anxious to rise to the same level. He determines to start off with his friends, Weir and Moxton, in an aerial boat which he finds ready to hand, does so, and arrives at the planet Venus, where he is left by his friends, and is beginning his explorations when the second part closes. The descriptions of the voyage are ingenious, though we cannot say that the writer has the wonderful art possessed by Jules Verne of making everything appear quite natural.

[I omit here a long extract from volume 1]

... It is useless to argue about probabilities when the whole plan of the romance is founded on impossibilities, else we should say the writer had a very crude idea of the Magellan clouds, and of the possibility of life outside an atmosphere, and so on. The “Coming Race” and a recent New Zealand work – “Erchomenon” – have familiarized the minds of most readers of this sort of literature to the possibilities of speculation, with electricity and the flying-machine for materials. These books have, however, a foundation of philosophy, and the great defect of the little work before us is that at present it seems to have little but wild fancy to commend it, and no substratum of philosophical ideas on which to build its shadowy superstructure, But, as we have said, there is more to come, and we have no desire to be hypercritical.

The only other contemporary comment laid emphasis solely on the primitive nature of the production, though it did do posterity the considerable service of naming the author for us (whether accurately or not is difficult to say - there seems no obvious reason to doubt the attribution, however):

AN ASHBURTON AUTHOR. – Mr. Henry Honor, a gentleman resident in Ashburton, has at present in the Press a work of imagination entitled “The Great Romance: by the Inhabitant.” The tale is an account of a perilous voyage amongst the stellar worlds, the voyageurs being three men, and their vessel a sort of half-and-half craft called the “Star Climber.” The first “volume,” a booklet of 55 octavo pages has been issued. It has suffered a good deal at the hands of the printer, whose work is decidedly not productive of a thing of beauty.

The principal modern critic of the story, Dominic Alessio, whose 2008 edition I have hitherto been quoting from, sees it in its contemporary context as:

a promotional piece encouraging emigration. As Clute and Nicholls point out [in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction], because of New Zealand’s distance from Old World centers of power, the colony became ‘a convenient setting for moral and Utopian tales’ … The emphasis on friendly aliens may even be part of a booster strategy intended to assure European readers concerned about rebellious Maori in the post-1860s New Zealand wars climate [xliv-v].

While Alessio is eager to claim that "

The Great Romance ... demonstrates that western representations of the Other are often far more complex and ambiguous than Said’s [

Orientalism] assumed" [xlvi], he is nevertheless forced to conclude that:

If one deconstructs the story as an alternative ontological history of contact between the Maori and the British over the course of the nineteenth century, one which merely uses the alien-human story as a surrogate for this relationship, then it is not surprising that things still turned out the way they did despite the initial optimism for cooperation that followed in the wake of the signing of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi [xlviii].

For myself, I hope that this post has made clear my sense that a lot of the haunting strangeness we can still feel in - especially - the second, Venusian, part of

The Great Romance comes from its strong roots in the local landscape.

Of course I realise that Ashburton in 2019 has little in common with the town that stood here in 1881, but such prominent features as the still spectacular Lake Heron can have changed little in the intervening 140-odd years. It

does seem strangely reminiscent of the 'Venuses' lake dwelling, while the basic lines of the town would not appear to have greatly altered either. And is it wrong of me to see something of Hope's "castle" in the extravagant lines of the local post-office?

More to the point, the feeling of intense dislocation which must have prompted the "inhabitant" (or should I say Mr. Henry Honor?) to start composing his interplanetary romance are still strongly in evidence for outside visitors. There seems something inevitable about the fact that a book based on that most puzzling of nineteenth-century poems, Lewis Carroll's immortal

Hunting of the Snark (1876), should also have been written here, also after an 140-year gap: David Elliot's

Snark: Being a True History of the Expedition That Discovered the Snark and the Jabberwock and Its Tragic Aftermath (2016).

David Elliot: Snark (2016)

David Elliot: Snark (2016)

The most surprising thing of all, perhaps, is the concerted efforts "the inhabitant" made to circulate his work. Volume One would appear to have been printed at the office of one of the local Ashburton newspapers (though volume Two was farmed out to the presses of the

Otago Daily Times in Dunedin). It seems doubtful that a third volume will ever now emerge from the stacks, but if it does I'll certainly be eager to know whether Hope is compelled by the better angels of his nature to leave the poor Venuses in peace - more to the point, whether Weir can ever be rescued from his Lucifer-like fall off the asteroid.

I'll never know, I guess. To be honest, I'm a little surprised that no-one has - as yet - undertaken to write a continuation of the story. Dickens' posthumous mystery story

Edwin Drood has been "finished" by numerous other authors. Why not

The Great Romance?