Emily, dir. & writ. Frances O'Connor - with Emma Mackey, Fionn Whitehead, Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Alexandra Dowling, Amelia Gething, Adrian Dunbar, Gemma Jones - (UK / USA, 2022)

Well, quite a bit, really. For a start, she and Branwell seem to be the only writers in the Brontë family, and his efforts aren't much cop - as she brutally informs him halfway through the film. Charlotte is a bespectacled geek who's put aside such childish things, and Anne's a poor waif who sways whichever way the wind is blowing. Which it does quite a bit, it being Yorkshire, and all of them stuck in some nowhere village in the back of beyond.

A bit of opium helps, and some sex with the local curate, but nothing really touches the tired spot till she sits down one day and starts writing on a blank sheet of paper - and lo and behold, there's a novel called Wuthering Heights!

Joking apart, I did greatly enjoy the film, and even found it quite moving in parts, just so long as I could suspend the inner literary historian - never an easy task, I'm afraid. I mean, I can understand eliding over all that complicated business about the three sisters' pseudonyms, Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell (was 'Currer' really a common first name at the time? It does seem a particularly egregious choice).

So, yes, I can see why, when a small package with a copy of her novel in it finally arrives in Haworth, it has the name 'Emily Brontë' on the titlepage. I don't like it, but I can, I suppose, accept it as a dramatic convenience.

But why was it necessary to edit out the other sisters' part in this literary revolution? Wuthering Heights first appeared in a three-volume package with Anne's novel Agnes Grey: two volumes for Emily, one volume for Anne. And owing to the dithering of their publisher, although it had been accepted earlier, their book didn't actually appear until after Charlotte's Jane Eyre had already come out from another firm and caused something of a literary sensation.

So the film's decision to show Charlotte sitting down to write her own novel in the wake of Emily's death, and thus - in a sense - carrying on her work, just doesn't seem a necessary fiction to me. I share director (and script-writer) Frances O'Connor's fierce appreciation of Emily's genius - she is, for me, the pick of the bunch, and her novel a masterpiece on a quite different level from Charlotte's and Anne's more numerous works.

I also understand why Emma Mackey, the actor who plays her so spiritedly, feels so protective of her. Emily Brontë is a writer who inspires affection rather than simple respect: her work did, after all, have to make its way against the odds. Charlotte's preface to the second, 'corrected' edition of Wuthering Heights could certainly be said to be damning it with faint praise; and of course in Anne's case she tried to suppress further editions of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall altogether, as she considered its subject matter unbecoming for a lady to acknowledge - let alone write about.

Emily was a genius or she was nothing. And I suppose it's for this reason that one can accept this fantasia on themes suggested by the life of Emily Brontë as a legitimate response to her. She's the only one of the three sisters who's ever been regarded as a poet of distinction, and the strange, clockwork machinery of her sublime Gothic novel belies any attempts that have been made since to write it off as hysterical melodrama.

Mind you, there's also the usual battle of the biographers to take into account. In this case the Brontë mythos (for want of a better word) was established early on by Charlotte's first biographer, the novelist Mrs. Gaskell.

She it was who first revealed the identity of the three sisters, as well as the secrets of their childhood: the massive corpus of juvenilia Charlotte and Branwell produced about Angria, while Emily and Anne collaborated on their own stories of Gondal.

The editorial efforts of renowned literary forger Thomas J. Wise to establish a reliable text of the the lives, works and correspondence of the entire family were, I suppose, the next major event in Brontë studies. They culminated in the 21-volume Shakespeare Head edition (1931-38).

This includes four volumes of The Brontës: Their Lives, Friendship and Correspondence; two volumes of the Miscellaneous and Unpublished Writings of Charlotte and Patrick Branwell Brontë, three volumes of poetry - Poems of Emily and Anne Brontë, Poems of Charlotte and Patrick Branwell Brontë, and Gondal Poems - as well as 11 volumes of novels and another of bibliography.

Given Wise's subsequent fall from grace, it's a bit distressing that this remains the best and most convenient edition of the family's complex and serried works: though the Oxford English Texts series has gradually superseded most of its component parts.

The next major player in the saga was the redoubtable Winifred Gérin (1901-1981), who wrote successive biographies of the entire Brontë family and their biographer over a period of twenty-odd years:

Anne Brontë (1959)Gérin's second husband, John Lock, another Brontë enthusiast, was the co-author, with Canon W. T. Dixon, of A Man of Sorrow: The Life, Letters, and Times of the Rev. Patrick Brontë, 1777-1861 (1965), thus completing the tally.

Branwell Brontë (1961)

Charlotte Brontë: The Evolution of Genius (1967)

Emily Brontë: A Biography (1971)

The Brontës (1973)

Elizabeth Gaskell: A Biography (1976)

Gérin, who lived in Haworth for many years, and regarded this as an essential foundation for insight into their works, approached the sisters with a blend of sympathy and indefatigable research into the physical context of their lives. She also, it must be said, provided a great deal of information about them which had not been available before. One reviewer of her prize-winning biography of Charlotte did, however, criticise it for lacking "the Yorkshire pith and terseness of the Brontë style."

Certainly that's the attitude taken by the sisters' next major biographer, Juliet Barker. She attempts to dispel the myths which have grown up around the family with a mixture of hard-headed scepticism and minute attention to detail. Emily, in particular, gets a bit of a caning in her account of the hotbed of genius that was the Brontë household.

So who should we believe? Mrs. Gaskell, who had the advantage of actually meeting and befriending Charlotte shortly before her death? Winifred Gérin, who clearly filled some inner need in herself by living on the Haworth moors with her imaginary friends, the sisters and their circle? Or Juliet Barker, whose undisguised scorn for her (allegedly) more credulous predecessors makes one wonder at times just who appointed her chief custodian of their posthumous reputations?

The literary donnybrook continues, as such things tend to do. In the meantime, though, we have six fascinating novels to read (and reread) by the three sisters - at least two of them, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, undoubted masterpieces. We also have a substantial number of poems by Emily: enough to guarantee her place among the English poets.

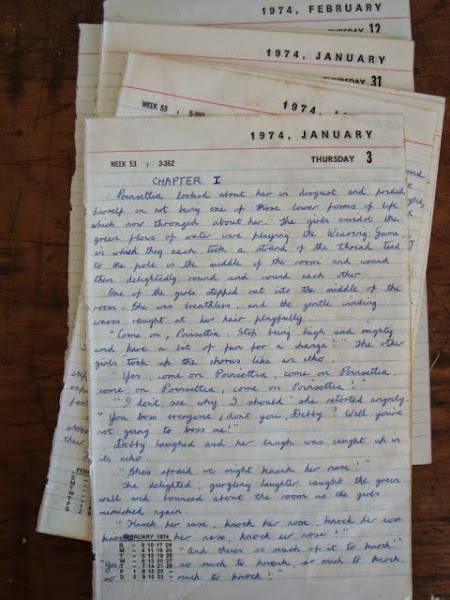

We also - as I discussed in an earlier post - have the ongoing revelation of the sheer extent and variety of the Brontës' surviving juvenilia. The various overlapping editions of that have now begun to rival editions of their own mature works.

- Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855)

- Branwell Brontë (1817-1848)

- Emily Brontë (1818-1848)

- Anne Brontë (1820-1849)

- Anthologies & Secondary Literature

[titles I own are marked in bold]:

-

Juvenilia:

- Stories & Poems (c.1830-1839)

- The Young Men's Magazine, Number 1 – 3 (August 1830)

- A Book of Ryhmes (1829)

- The Spell

- The Secret

- Lily Hart

- The Foundling

- The History of the Year

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- A Romantic Tale

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Characters of Celebrated Men

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Albion and Marina

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- The Bridal

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Tales of the Islanders

- Tales of Angria (1838–1839)

- Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Passing Events

- Included in: Five Novelettes. Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts and Edited by Winifred Gérin. London: The Folio Press, 1971.

- Julia

- Included in: Five Novelettes. Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts and Edited by Winifred Gérin. London: The Folio Press, 1971.

- Mina Laury

- Included in: Five Novelettes. Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts and Edited by Winifred Gérin. London: The Folio Press, 1971.

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Included in: Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Stancliffe's Hotel

- Stancliffe's Hotel. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2003.

- Included in: Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- The Duke of Zamorna

- Included in: Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Henry Hastings

- Included in: Five Novelettes. Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts and Edited by Winifred Gérin. London: The Folio Press, 1971.

- Included in: Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Caroline Vernon

- Included in: Five Novelettes. Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts and Edited by Winifred Gérin. London: The Folio Press, 1971.

- Included in: Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- The Roe Head Journal Fragments

- Included in: Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Something about Arthur

- Something about Arthur. Ed. Christine Alexander. The University of Texas at Austin: Humanities Research Center, 1981.

- My Angria and the Angrians

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Farewell to Angria

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- [as Lord Charles Albert Florian Wellesley] The Green Dwarf, A Tale of the Perfect Tense (1833)

- The Professor; Tales from Angria ['The History of the Year' / 'A Romantic Tale' / 'Characters of Celebrated Men' / 'Albion and Marina' / 'The Bridal' / 'My Angria and the Angrians' / 'Mina Laury' / 'Farewell to Angria']; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Five Novelettes: Passing Events; Julia; Mina Laury; Henry Hastings; Caroline Vernon. Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts and Edited by Winifred Gérin. London: The Folio Press, 1971.

- Something about Arthur. Transcribed from the Original Manuscript and Edited by Christine Alexander. The University of Texas at Austin: Humanities Research Center, 1981.

- The Juvenilia of Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë. Ed. Frances Beer. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

- Alexander, Christine, ed. An Edition of the Early Writings of Charlotte Brontë. 3 vols. Shakespeare Head Press. Oxford & New York: Basil Blackwell, 1987-91.

- Volume I: The Glass Town Saga, 1826-1832 (1987)

- Volume II: The Rise of Angria, 1833-1835. Part 1: 1833-1834 (1991)

- Volume II: The Rise of Angria, 1833-1835. Part 2: 1834-1835 (1991)

- Juvenilia 1829-1835. Ed. Juliet Barker. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1996.

- Stancliffe's Hotel. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2003.

- Tales of Angria: Mina Laury; Stancliffe's Hotel; The Duke of Zamorna; Henry Hastings; Caroline Vernon; The Roe Head Journal Fragments. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- [as 'Currer Bell'] Jane Eyre (1847)

- Jane Eyre. 1847. Introduction by Margaret Lane. Everyman’s Library, 287. 1908. London: J. M. Dent & Sons / New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1953.

- Jane Eyre. 1847. Introduction by Bonamy Dobrée. 1953. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1977.

- [as 'Currer Bell'] Shirley (1849)

- Shirley. 1849. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1953. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1977.

- [as 'Currer Bell'] Villette (1853)

- Villette. 1853. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1953. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1975.

- The Professor (1857)

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Emma: A Fragment (1860)

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846)

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Shorter, Clement, ed. The Complete Poems of Charlotte Brontë, Now for the First Time Collected, with Bibliography and Notes, by C. W. Hatfield. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., 1923.

- Gaskell, Elizabeth. The Life of Charlotte Brontë. 1857. Ed. Alan Shelston. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Gérin, Winifred. Charlotte Brontë: The Evolution of Genius. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

- Jane Eyre, dir. Cary Fukunaga, writ. Moira Buffini (based on the novel by Charlotte Brontë) – with Mia Wasikowska, Michael Fassbender – (USA, 2011).

Novels:

Poetry:

Secondary:

•

[There are, of course, many adaptations of Jane Eyre. This is definitely one of the better ones, though possibly the most interesting of all is Val Lewton's I Walked with a Zombie (1943).]

-

Juvenilia:

- Stories & Poems (c.1830-1839)

- Battell Book

- The Glass Town

- The Young Men's Magazine, Number 1 – 3 (August 1830)

- The Revenge A Tradgedy

- The History of the Young Men from Their First Settlement to the Present Time (1829–1831)

- The Fate of Regina

- The Liar Detected

- Ode on the Celebration of the Great African Games

- The Pirate A Tale

- Real Life in Verdopolis, volume 1–2

- The Politics of Verdopolis

- An Angrain Battle Song

- Percy's Musings upon the Battle of Edwardston

- Mary's Prayer

- An Historical Narrative of the War of Encroachment

- An Historical Narrative of the War of Agression

- Angria and the Angrians

- Letters from an Englishman (1830–1832)

- Life of Warner Howard Warner

- Tales of Angria (1838–1839)

- Tales of Angria. 1837-39. Ed. Heather Glen. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

- Winnifrith, Tom, ed. The Poems of Patrick Branwell Brontë: A New Annotated and Enlarged Edition of the Shakespeare Head Brontë. The Shakespeare Head Press. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher Limited, 1983.

- The Works of Patrick Branwell Brontë. Ed. Victor A. Neufeldt. 3 vols. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997-1999.

- du Maurier, Daphne. The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

- Gérin, Winifred. Branwell Brontë: A Biography. 1961. A Radius Book. London: Hutchinson & Co (Publishers ) Ltd., 1972.

- Wainwright, Sally. To Walk Invisible (BBC, 2016)

Poetry:

Works:

Secondary:

•

[A number of actors have now had the dubious distinction of playing poor Branwell Brontë, among them Michael Kitchen in The Brontës of Haworth (1973), Adam Nagaitis in To Walk Invisible (2016), and now, in Emily (2022), Fionn Whitehead.]

-

Novels:

- [as 'Ellis Bell'] Wuthering Heights: A Novel (1847)

- Wuthering Heights. 1847. Introduction by Bonamy Dobrée. 1953. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1977.

- Wuthering Heights. An Authoritative Text, with Essays in Criticism. 1847. Ed. William M. Sale, Jr. A Norton Critical Edition. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1963.

- Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846)

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Shorter, Clement, ed. The Complete Poems of Emily Jane Brontë, Arranged and Collated, with Bibliography and Notes, by C. W. Hatfield. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., 1923.

- Emily Jane Brontë: The Complete Poems. Ed. C. W. Hatfield. 1941. New York & London: Columbia University Press & Oxford University Press, 1963.

- The Complete Poems of Emily Brontë. Ed. Philip Henderson. London: The Folio Society, 1951.

- Gondal's Queen: A Novel in Verse by Emily Brontë. Ed. Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford. Austin: University of Texas Press / London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Limited, 1955.

- The Complete Poems. Ed. Janet Gezari. Penguin English Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992.

- Gérin, Winifred. Emily Brontë: A Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Wuthering Heights, dir. & writ. Elisaveta Abrahall (based on the novel by Emily Brontë) – with Paul Eryk Atlas & Sha'ori Morris – (UK, 2018).

Poetry:

Secondary:

•

[There's a huge number of film adaptations of Wuthering Heights. Wikipedia lists at least 13, though it misses the one pictured below. Probably the most memorable remains William Wyler's 1939 movie, with Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon. Despite its obvious lacunae, it's attained an almost mythic status among cinéastes.]

-

Novels:

- [as 'Acton Bell'] Agnes Grey (1847)

- Included in: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall & Agnes Grey. 1848 & 1847. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1977.

- [as 'Acton Bell'] The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848)

- Included in: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall & Agnes Grey. 1848 & 1847. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1977.

- Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846)

- Included in: The Professor; Tales from Angria; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954. Collins Gift Classics. London: Collins, 1976.

- Gérin, Winifred. Anne Brontë. London: Thomas Nelson, 1959.

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, dir. Mike Barker, writ. David Nokes & Janet Barron (based on the novel by Anne Brontë) – with Toby Stephens, Tara Fitzgerald, Rupert Graves – (UK, 1996).

Poetry:

Secondary:

•

[There are at least two television adaptations of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the one pictured below and a 1968 version as well. It's also been adapted for the stage on a number of occasions.]

- The Works of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Illustrations by A. S. Greig. Ornaments by T. C. Tilney. 12 vols. 1893. London: J. M. Dent, 1895-96.

- Jane Eyre, by Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë). Vol. 1 of 2. Introduction by F. J. S. (1896)

- Jane Eyre. Vol. 2 of 2 (1896)

- Shirley, by Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë). Vol. 1 of 2. Introduction by F. J. S. (1896)

- Shirley. Vol. 2 of 2 (1896)

- [Villette, by Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë). Vol. 1 of 2.]

- [Villette. Vol. 2 of 2.]

- The Professor, by Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë). Introduction by F. J. S. 1893 (1895)

- Poems of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. With Cottage Poems by Patrick Brontë, Introduction by F. J. S. (1896)

- [Wuthering Heights, by Ellis Bell (Emily Brontë). Vol. 1 of 2. Introduction by F. J. S.]

- Wuthering Heights. Vol. 2 of 2. Agnes Grey, by Acton Bell (Anne Brontë). Introduction by F. J. S. (1896)

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, by Acton Bell (Anne Brontë). Vol. 1 of 2. Introduction by F. J. S. (1893)

- The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, by Acton Bell (Anne Brontë). Vol. 2 of 2 (1893)

- The Brontës. Collins Gift Classics. 1953-54. London: Collins, 1975-1977.

- Brontë, Anne. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall & Agnes Grey. 1848 & 1847. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1954 (1977)

- Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. 1847. Introduction by Bonamy Dobrée. 1953 (1977)

- Brontë, Charlotte. Shirley. 1849. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1953 (1977)

- Brontë, Charlotte. Villette. 1853. Introduction by Phyllis Bentley. 1953 (1975)

- Brontë, Charlotte. The Professor; Tales from Angria ['The History of the Year' / 'A Romantic Tale' / 'Characters of Celebrated Men' / 'Albion and Marina' / 'The Bridal' / 'My Angria and the Angrians' / 'Mina Laury' / 'Farewell to Angria']; Emma: A Fragment / Together with a Selection of Poems by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Ed. Phyllis Bentley. 1954 (1976)

- Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. 1847. Introduction by Bonamy Dobrée. 1953 (1977)

- The Brontës. Selected Poems. Ed. Juliet R. V. Barker. Everyman. 1985. London: J. M. Dent / Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle, 1993.

- The Brontës. Tales of Glass Town, Angria, and Gondal: Selected Writings. Ed. Christine Alexander. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Barker, Juliet. The Brontës. 1994. A Phoenix Giant Paperback. London: Orion Books Ltd., 1995.

- Barker, Juliet. The Brontës: A Life in Letters. London: Viking, 1997.

- Barker, Juliet. The Brontës: A Life in Letters. 1997. Rev. ed. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 2016.

- Bentley, Phyllis. The Brontës and Their World. 1969. London: Thames & Hudson, 1974.

- Clarke, Pauline. The Twelve and the Genii. Illustrated by Cecil Leslie. 1962. Faber Paper Covered Editions. London: Faber, 1970.

- Gérin, Winifred. The Brontës. London: Longmans, 1973.

- Gérin, Winifred. Elizabeth Gaskell: A Biography. 1976. Oxford Paperbacks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Miller, Lucasta. The Brontë Myth. London: Jonathan Cape, 2001.

- Ratchford, Fannie Elizabeth. The Brontës’ Web of Childhood. 1941. New York: Columbia University Press, 1949.

- The Brontës of Haworth: 4-part miniseries, dir. Marc Miller, writ. Christopher Fry – with Alfred Burke, Vickery Turner, Ann Penfold, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, Michael Kitchen, Rosemary McHale – (UK, 1973). 2-DVD set.

•

•

[Despite having been made almost fifty years ago, The Brontës of Haworth remains a remarkably convincing version of the family story. A good deal of this has to be attributed to renowned British playwright Christopher Fry's superlative script. It's an exceptionally grim and depressing tale, mind you - and the series makes no attempt to disguise this. The recurring motif of the sisters walking and talking around the kitchen table until finally there's only Charlotte left is still quite haunting. Fry also does a good job of humanising the often overlooked Anne.]