Boris Pasternak. Doctor Zhivago. 1957. Trans. Nicolas Pasternak Slater. Illustrated by Leonid Pasternak. Introduction by Ann Pasternak Slater. 2019. 2 vols. London: The Folio Society, 2020.

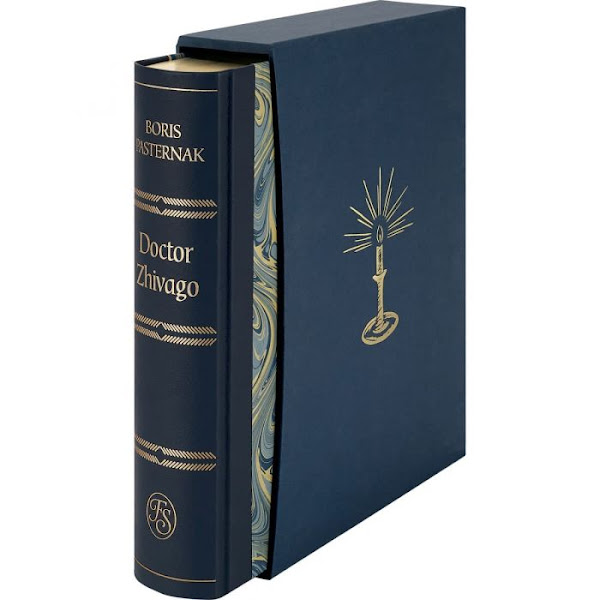

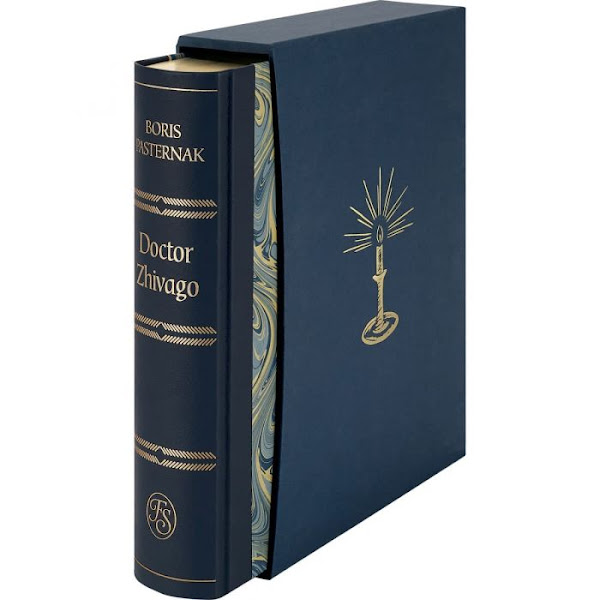

For my birthday this year I asked for the book above, the beautifully bound and illustrated new translation of Boris Pasternak's

Doctor Zhivago by his nephew Nicolas Pasternak Slater.

Boris Pasternak: Doctor Zhivago (Limited Edition: Folio Society, 2019)

Boris Pasternak: Doctor Zhivago (Limited Edition: Folio Society, 2019)

The book actually first came out last year as a limited edition, but there was so much demand for it that the Folio Society decided to reissue a slightly scaled-down version of it for less wealthy readers (such as myself).

Пастернак, Борис. Доктор Живаго. 1957. Milano: Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, 1961.

For those of you unfamiliar with the book's history, the Russian text was first published in Italy, from a smuggled typescript, then reprinted in translations in various languages throughout the world.

Doctor Zhivago. 1957. Trans. Max Hayward & Manya Harari. 1958. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1959.

As you can see from the dustjacket of the English version, above, it won Boris Pasternak the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958 - or, rather, earned him the

offer of the prize. Pasternak was threatened with the imprisonment of some of his nearest and dearest if he didn't turn it down, and he spent the short remainder of his life - he died in 1960 - in deep disgrace with the Soviet Regime.

As the poet's niece, literary critic Ann Pasternak Slater, has explained:

The dangers originally posed by Pasternak's prose are inconceivable to the modern reader. In the 70s, I met a Russian who told me, rather sourly, that he'd served six years in the camps for possessing a samizdat chunk of Doctor Zhivago. Ten pages of blurry carbon copy. "Oh dear," I said; "I hope it was worth it." "Worth it! A chapter of nature description?"

Doctor Zhivago, dir. David Lean, writ. Robert Bolt – with Omar Sharif, Julie Christie, Alec Guinness – (USA, 1965).

So is that what the book is actually like? Those of you more familiar with the film version above will certainly find quite a few surprises in it. It's far less melodramatic and far more meditative - as befits a poet as complex as Pasternak - than you'd ever expect from the David Lean epic.

Robert Bolt. Doctor Zhivago: The Screenplay. Based on the Novel by Boris Pasternak. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1965.

That's not to say that Robert Bolt didn't do a great job of adapting it for the screen - it may not quite match his screenplay for

Lawrence of Arabia, but then, what does? There were, however, certain elements of Pasternak's slow-moving and poetic text that were bound to take a backseat in this switch to another medium.

Doctor Zhivago. 1957. Trans Max Hayward & Manya Harari. 1958. Fontana Modern Novels. London: Collins Fontana, 1974.

What about the English translation itself? How good was it? In her

review of the 2010 retranslation of the novel by industrious duo Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Ann Pasternak Slater fills in the background a bit:

Doctor Zhivago was first translated, at great speed, by Max Hayward and Manya Harari in 1958. I remember Max saying he would read a page in Russian, and then write it down in English, without looking back. This sounds incredible – even though a page of the large-faced Russian typescript they worked from is roughly equivalent to only half a page of their Collins text. I can, though, readily believe that he did this with paragraphs and sentences. Of course both translators then cross-checked and agreed their combined version against the original. Nevertheless, it's perfectly true that there are negligible omissions which are made good in the Volokhonsky-Pevear translation.

The reason for this almost indecent haste was the perceived need - mainly for reasons of Cold War politics - to get this novel into the hands of readers as soon as humanly possible. In her own

review of the 2019 Folio Society version, Harvard librarian Christine Jacobson comments:

In their translators’ note, Hayward and Harari expressed their wish to see the novel appear in Russian and, eventually, to “fall into the hands of a translator whose talent is equal to that of its author.” This note may sound charmingly self-deprecating to readers, but Hayward and Harari had been given just three months to translate Pasternak’s lengthy text. They were, as they say in their introduction, under no illusions that they had done justice even remotely to the original.

All of which brings us back to the subject of tne translation team of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. It's perhaps, now, the central controversy for readers of classic Russian books in English. What do you think of them? If you look up their numerous versions of Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Turgenev

online, you'll find a chorus of superlatives about the pair.

Nor has Pevear, in particular, been backward in criticising the shortcomings of earlier translations - by such luminaries as Constance Garnett, David Magarshack, Michael Glenny, and Max Hayward - of the works the two of them have put out in tandem.

Apparently this applies to French literature as well as Russian. Pevear comments in the preface to his version of Alexandre Dumas'

The Three Musketeers that most modern translations available today are 'textbook examples of bad translation practices' which 'give their readers an extremely distorted notion of Dumas' writing.'

On the other hand, their work has not been without its critics. Czech psychoanalyst and art critic Janet Malcolm [née Jana Wienerová] said of the two in 2016 that Pevear and Volokhonsky 'have established an industry of taking everything they can get their hands on written in Russian and putting it into flat, awkward English'. Slavonic Studies Academic Gary Saul Morson wrote in

Commentary in 2010 that Pevear and Volokhonsky translations 'take glorious works and reduce them to awkward and unsightly muddles.'

I touched on this matter once before, in a post extolling the merits of

Constance Garnett's translations from the Russian:

Another important thing to remember about translation in general is that the texture of the translator's prose is probably more important in creating an impression on the reader than the actual literal accuracy of each phrase. The latest translation of a book is not necessarily the best.

While I didn't include Pevear / Volokhonsky's translation in my comparative table of versions of the opening passage of

Anna Karenina, I

was aware of the existence of their recent re-translation of Bulgakov's

Master and Margarita, which does not (in my opinion, at any rate) live up to the hype surrounding it. Since it's the only one of their books I own, it seemed impertinent to offer any further views on the matter at the time.

Boris Pasternak: Doctor Zhivago, trans. Richard Pevear & Larissa Volokhonsky (2010)

Boris Pasternak: Doctor Zhivago, trans. Richard Pevear & Larissa Volokhonsky (2010)

So, anyway, to make a long story short, in 2010 Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky decided to turn their attention to Boris Pasternak's famous novel, due - as usual - to the alleged shortcomings of the existing English version. In fact, as their

Amazon.com page declares:

Pevear and Volokhonsky masterfully restore the spirit of Pasternak's original — his style, rhythms, voicings, and tone — in this beautiful translation of a classic of world literature.

So far, so good. Unfortunately for them, the Pasternak family has many branches, including a large and literate set of descendants resident in the UK. One of these,

Ann Pasternak Slater, found the tone of their version far from impressive. She concluded her

Guardian review of it as follows:

Not inaccurate, and lacking everything.

Her views are worth considering at more length, however, based as they are on so much concentrated

familial as well as scholarly expertise:

Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear's recent translations of Tolstoy have been universally acclaimed. They come to Doctor Zhivago with an enviable reputation. Harvill Secker's publicity material promises that in "this stunning new translation" they "have restored material omitted from the original translation, as well as the rhythms, tone, precision, and poetry of Pasternak's original". A vague and daunting claim. Can it be sustained?

...

On a first reading, one is distracted by locutions that are somehow not quite right – often not strikingly, but continuously and insidiously so. They just don't sound English. The terrorist "was serving at hard labor". "Pavel had gone to bathe in the river and had taken the horses with him for a bath." (Hayward-Harari have "Pavel had gone off to bathe in the river and had taken the horses with him.") He "fell to thinking" ("stood thoughtfully"). "The spouses went rolling off" ("The couple drove off").

Sustained, low-level unease is intensified by un-English word-order. "Yura was pleased that he would again meet Nika." Inversions (ubiquitous in early Conrad) are natural to foreigners speaking English and a mistake in translators. The inversion of subject and verb, aggravated by an invasive parenthesis, is an elementary translator's error. "At the turn there would appear, and after a moment vanish, the seven-mile panorama of Kologrivovo." It is quickly apparent that Volokhonsky-Pevear follow the Russian very closely, without attempting to reconfigure its syntax or vocabulary into a more English form.

This misguided literalism is disastrous in dialogue. "Yes, yes, it's vexing in the highest degree that we didn't see each other yesterday" ("Oh, I wish I'd seen you yesterday").

Russian is liberal with knee-jerk invocations and imprecations. Volokhonsky-Pevear solemnly translate word for word; Hayward-Harari naturalise. "As God is my witness, I'd spit on you all" ("I'd chuck the lot of you, honest to God I would"). In Russian, "mne naplivat' na ..." literally means "I spit on", but conveys, more weakly, "I don't give a toss", "too bad about ..." Not so for Volokhonsky-Pevear: "Ah, spit on the rugs and china, let it all go to hell" ("Do stop worrying about rugs ...").

...

It's instructive to check Volokhonsky-Pevear's English against the Russian. Its painful ineptitudes can regularly be defended by a Russian source. Yet the original isn't inept. It's simply been badly translated. Pasternak's Russian is packed, concise, colloquial and muscular. Volokhonsky-Pevear's English is prosaic, flabby and verbose. It often renders Pasternak's more philosophical passages incomprehensible. It's far worse than the compact, natural and always lucid prose of Hayward and Harari.

These differences prompt questions about accuracy. When Volokhonsky-Pevear write: "Having performed his traveling ablutions in pre-war comfort", they translate the Russian word for word, and it sounds absurd. Hayward-Harari turn what it implies into easy English ("He washed and shaved in pre-war comfort"). This was certainly one of Pasternak's principles as a translator. In his great translations of Shakespeare he cut, compressed, paraphrased and invented freely. He wrote Shakespeare in Russian.

It is, perhaps, too easy to criticise Volokhonsky and Pevear. What about the sustained liberties taken by Hayward and Harari? Are they justified? Here we come to Pasternak's obscurity.

A small example. Volokhonsky-Pevear introduce us to a showy figure at the station, enigmatically wearing "an expensive fur coat trimmed with railway piping". What does that mean? The unusual Russian adjective, "puteiskii", suggests the function of a railway engineer. Hayward-Harari hazard an explanation: "an expensive fur-lined coat on which the piping of the railway uniform had been sewn". The italicised words have no textual basis. Which is better? To trip up the reader on a trivial enigma, or to try to make sense of it?

...

Turning to Zhivago's poems, I have to declare an interest. My mother translated her brother's poems. Boris's poetry is formally rich, regularly rhymed, and metrically precise. It is full of delectable assonances, at once musical and wholly natural. My mother's first priority was to reproduce his aural effects. She did. This difficult demand inevitably exacted its own price. Her English is flawed – it sounds Russian. But it sings, as Pasternak's poetry does. Its quaintness is authentic, like Garnett's period translations of Tolstoy.

There are many bad translations of Pasternak's poems. Volokhonsky and Pevear's are no worse than the rest. They're what Nabokov called his translation of Pushkin's Onegin – "a pony". A humble pack-horse. A prose crib, dutifully set out in pointless short lines mimicking the original.

Of course, there may be such a thing as being

too close to your subject. Certainly Ann Pasternak Slater is right to 'declare an interest.' After all, plenty of other readers seem to have enjoyed the new translation.

On the other hand, there is the old 'if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck' principle to be considered. Going back to Janet Malcolm's pitiless demolition of the Volokhonsky-Pevear cottage translation industry ('

Socks' -

New York Review of Books, June 23, 2016), we see much the same set of complaints coming up in relation to their 2000 translation of Tolstoy's

Anna Karenina:

In Anna Karenina, the day after the fateful ball, resolved to forget Vronsky and resume her peaceful life with her son and husband (“my life will go on in the old way, all nice and as usual”), Anna settles herself in her compartment in the overnight train from Moscow to St. Petersburg, and takes out an uncut English novel, probably one by Trollope judging from references to fox hunting and Parliament. Tolstoy, of course, says nothing about a translation — educated Russians knew English as well as French. In contrast, very few educated English speakers have read the Russian classics in the original and, until recent years, they have largely depended on two translations, one by the Englishwoman Constance Garnett and the other by the English couple Louise and Aylmer Maude, made respectively in 1901 and 1912. The distinguished Slavic scholar and teacher Gary Saul Morson once wrote about the former:

I love Constance Garnett, and wish I had a framed picture of her on my wall, since I have often thought that what I do for a living is teach the Collected Works of Constance Garnett. She has a fine sense of English, and, especially, the sort of English that appears in British fiction of the realist period, which makes her ideal for translating the Russian masterpieces. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were constantly reading and learning from Dickens, Trollope, George Eliot and others. Every time someone else redoes one of these works, reviewers say that the new version replaces Garnett; and then another version comes out, which, apparently, replaces Garnett again, and so on. She must have done something right.

Morson wrote these words in 1997, and would recall them bitterly. Since that time a sort of asteroid has hit the safe world of Russian literature in English translation. A couple named Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky have established an industry of taking everything they can get their hands on written in Russian and putting it into flat, awkward English. Surprisingly, these translations, far from being rejected by the critical establishment, have been embraced by it and have all but replaced Garnett, Maude, and other of the older translations. When you go to a bookstore to buy a work by Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Gogol, or Chekhov, most of what you find is in translation by Pevear and Volokhonsky.

In an article in the July/August 2010 issue of Commentary entitled “The Pevearsion of Russian Literature,” Morson used the word “tragedy” to express his sense of the disaster that has befallen Russian literature in English translation since the P & V translations began to appear. To Morson “these are Potemkin translations — apparently definitive but actually flat and fake on closer inspection.” Morson fears that “if students and more-general readers choose P & V … [they] are likely to presume that whatever made so many regard Russian literature with awe has gone stale with time or is lost to them.”

In the summer of 2015 an interview with the rich and happy couple appeared in The Paris Review. The interviewer — referring to a comment Pevear had made to David Remnick in 2005 — asked him: “You once said that one of your subliminal aims as a translator was ‘to help energize English itself.’ Can you explain what you mean?” Pevear was glad to do so:

It seemed to me that American fiction had become very bland and mostly self-centered. I thought it needed to break out of that. One thing I love about translating is the possibility it gives me to do things that you might not ordinarily do in English. I think it’s a very important part of translating. The good effect of translating is this cross-pollination of languages. Sometimes we get criticized — this is too literal, this is a Russianism — but I don’t mind that. Let’s have a little Russianism. Let’s use things like inversions. Why should they be eliminated? I guess if you’re a contemporary writer, you’re not supposed to do it, but as a translator I can. I love this freedom of movement between the two languages. I think it’s the most important thing for me — that it should enrich my language, the English language.

This bizarre idea of the translator’s task only strengthens one’s sense of the difficulty teachers of Russian literature in translation face when their students are forced to read the Russian classics in Pevear’s “energized” English. I first heard of P & V in 2007 when I received an e-mail from the writer Anna Shapiro:

I finished the Pevear/Volokhonsky translation of Anna Karenina a few weeks ago and I’m still more or less stewing about it. It leaves such a bad taste; it’s so wrong, and so oddly wrong, turning nourishment into wood. I wouldn’t have thought it possible. I’ve always maintained that Tolstoy was unruinable, because he’s such a simple writer, words piled like bricks, that it couldn’t matter; that he’s a transparent writer, so you can’t really get the flavor wrong, because in many ways he tries to have none. But they have, they’ve added some bad flavor, whereas even when Garnett makes sentences like “Vronsky eschewed farinaceous foods” it does no harm … I imagine Pevear thinking he’s CORRECTING Tolstoy; that he’s really the much better writer.

Ouch! No-one ever accused Janet Malcolm of pulling her punches when it comes to literary controversy ...

Mind you, one obvious reponse would be to say that if you're so smart, why don't

you do better? If there

are inaccuracies in some of the older translations of Russian literature, why be so critical of Pevear / Volokhonsky's attempts to correct them?

And while Malcolm may treat with scorn Richard Pevear's view that a few added Russianisms might enrich the flat contemporary dullness of English literary idioms, this is a standard argument offered in favour of such classic translations as The King James Bible (1611), North's

Plutarch (1579) and even John Florio's

Montaigne (1603). The comparison may seem grotesque, but each of those versions has been praised for making a strong contribution to English literature and the English language.

Unfortunately for Pevear and Volokhonsky, the Pasternak family, in particular, has not taken this challenge lying down. The new Folio Society translation of

Doctor Zhivago by the poet's nephew, Nicolas Pasternak Slater, is nothing if not a family affair. It includes illustrations by his grandfather - Boris's father - Leonid Pasternak, selected by his mother Maya Slater, as well as an introduction by his sister Ann Pasternak Slater. The question, however, must still remain whether or not it's any better than Pevear and Volokhonsky's - let alone Max Hayward and Manya Harari's rushed version of 1958?

While I (alas) am not really qualified to say, the same is not true of Russophile and assistant curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Harvard University’s Houghton Library Christine Jacobson, who reviewed it earlier this year in the

LA Review of Books (5/3/20):

[The] second translation was done by the husband-and-wife team Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky for the 50th anniversary of Pasternak’s death in 2010. Unfortunately, justice still eluded Zhivago. While the Hayward-Harari version has long been criticized for its divergence from Pasternak’s original prose, Pevear and Volokhonsky demonstrated another flaw — slavish devotion to its Russian syntax. Consequently, the novel’s reputation in the West has suffered. Zhivago is now part of Russia’s 11th-grade school curriculum, but many Slavic departments in the West gave up on the novel long ago, siding with Nabokov, who dismissed it as a “clumsy, trivial, and melodramatic” book. ...

Pasternak Slater’s translation definitively wooed me when I reached my favorite part of the novel. Having not seen Lara Antipova since they served together as medical volunteers in World War I, Yuri Zhivago spots her from across the room in a small-town library on the edge of the Ural Mountains. Several years have passed since he last saw her; the Russian Revolution has driven him and his family from Moscow to his wife Tonya’s former estate near Yuriatin, the town where, unbeknownst to Yuri, Lara lives. As a librarian, I can’t resist the romance of this serendipitous encounter in a library reading room. Unfortunately, the Pevear-Volokhonsky version is confounding:

He saw her almost from behind, her back half turned. She was wearing a light-colored checkered blouse tied with a belt, and was reading eagerly, with self-abandon, as children do, her head slightly inclined towards her right shoulder. Now and then she lapsed into thought, raising her eyes to the ceiling or narrowing them and peering somewhere far ahead of her, and then again, propped on her elbow, her head resting on her hand, in a quick sweeping movement she penciled some notes in her notebook.

This passage raises several questions. How does one see another person “almost from behind”? If Yuri can hardly see her, how can he observe her raising and narrowing her eyes? And why does Lara seem to be pantomiming the act of reading? Hayward and Harari’s version is even more confusing, alleging that Yuri sees her “side-face, almost from the back.” Pasternak Slater makes this scene much clearer:

He could see her profile, half turned away from him. She was wearing a light-coloured check blouse with a belt, and was immersed in what she was reading, oblivious of everything else, like a child. Her head was bent a little to one side, towards her right shoulder. From time to time she looked up at the ceiling, lost in thought, or screwed up her eyes and stared straight ahead; then she would lean her elbows back on the table, prop her head on one hand and copy something down into her notebook with a brisk, sweeping flourish of her pencil.

I've decided to supplement Jacobson's choice of these two translations of this particular passage (from the 'Varykino' chapter in part two of the novel) with the original version by Max Haywood and Manya Harari:

He saw her side-face, almost from the back. She wore a light check blouse with a belt and she sat, lost in her book, utterly absorbed in it, like a child, her head bent slightly over her right shoulder. Occasionally she stopped to think, looked up at the ceiling or straight in front of her, then again propped her cheek on her hand and wrote in her notebook with a swift, sweeping movement of her pencil.

The first thing that strikes me about these three versions of the same paragraph is the comparative wordiness of

both of the new translations. Haywood-Harari clock in at 76 words; Pevear-Volokhonsky at 86; Pasternak Slater at a record-breaking 101.

What, then, of Boris Pasternak himself?

Он видел ее спины, вполоборота, почти сзади. Она была в светлой клетчатой блузе, перехваченной кушаком, и читала увлеченно, с самозабвением, как дети, сколнив голову немного набок, к правому плечу. Иногда она задумывалась, поднимая глаза к потолку или, щурась, заглядывалась куда-то вдаль перед собой, а потом снова облокачивалась, подпирала голову рукой, и быстрым размашистрым движением записывала карандашом в тетрадь выноски из книги.

Pasternak's 'packed, concise, colloquial and muscular' Russian prose (in Ann Pasternak Slater's phrase) gets the whole thing done in 61 words. How does he do it? Let's look at the passage in a bit more detail:

Он видел ее спины, вполоборота, почти сзади.

On videl yeye spiny, vpoloborota, pochti szadi.

[He saw her back, half-turned, almost from behind.]

Она была в светлой клетчатой блузе, перехваченной кушаком, и читала увлеченно, с самозабвением, как дети, сколнив голову немного набок, к правому плечу.

Ona byla v svetloy kletchatoy bluze, perekhvachennoy kushakom, i chitala uvlechenno, s samozabveniyem, kak deti, skolniv golovu nemnogo nabok, k pravomu plechu.

[She was in a light checked blouse, divided by a sash, and read with enthusiasm, with abandon, as children do, tilting her head a little to one side, to her right shoulder.]

Иногда она задумывалась, поднимая глаза к потолку или, щурась, заглядывалась куда-то вдаль перед собой, а потом снова облокачивалась, подпирала голову рукой, и быстрым размашистрым движением записывала карандашом в тетрадь выноски из книги.

Inogda ona zadumyvalas', podnimaya glaza k potolku ili, shchuras', zaglyadyvalas' kuda-to vdal' pered soboy, a potom snova oblokachivalas', podpirala golovu rukoy, i bystrym razmashistrym dvizheniyem zapisyvala karandashom v tetrad' vynoski iz knigi.

[Sometimes she meditated, raising her eyes to the ceiling or squinting, peering into the distance in front of her, and then leaning back again, propping her head up with her hand, and with a quick sweeping movement wrote down quotes from the book with a pencil in her notebook.]

English is a far more wordy language than Russian, due - in part - to such differences as the need for definite and indefinite articles and frequent reiterations of personal pronouns in the former. Russian, as an inflected language, can maintain clarity through its system of declensions and cases. Even an almost completely literal translation, like the one in square brackets above, takes 89 words to express the 61 words of Pasternak's original.

More to the point, though, note how the three sentences in the paragraph start off simply, then build into a crescendo of detail. This is one of the crucial moments in the novel, and a lot of careful attention has clearly been lavished on it. The first, most concise sentence has 7 words, the second 22, and the third - with its interpolated subordinate phrases - 32: a textbook example of

incremental repetition, a technique perhaps more familiar in ballad poetry than in literary prose.

What do our three sets of translators do with this aspect of the paragraph?

Here's Haywood-Harari (1958):

He saw her side-face, almost from the back. [8]

She wore a light check blouse with a belt and she sat, lost in her book, utterly absorbed in it, like a child, her head bent slightly over her right shoulder. [31]

Occasionally she stopped to think, looked up at the ceiling or straight in front of her, then again propped her cheek on her hand and wrote in her notebook with a swift, sweeping movement of her pencil. [37]

Here's Pevear-Volokhonsky (2010):

He saw her almost from behind, her back half turned. [10]

She was wearing a light-colored checkered blouse tied with a belt, and was reading eagerly, with self-abandon, as children do, her head slightly inclined towards her right shoulder. [28]

Now and then she lapsed into thought, raising her eyes to the ceiling or narrowing them and peering somewhere far ahead of her, and then again, propped on her elbow, her head resting on her hand, in a quick sweeping movement she penciled some notes in her notebook. [48]

And here's Pasternak Slater (2019):

He could see her profile, half turned away from him. [10]

She was wearing a light-coloured check blouse with a belt, and was immersed in what she was reading, oblivious of everything else, like a child. [25]

Her head was bent a little to one side, towards her right shoulder. [13]

From time to time she looked up at the ceiling, lost in thought, or screwed up her eyes and stared straight ahead; then she would lean her elbows back on the table, prop her head on one hand and copy something down into her notebook with a brisk, sweeping flourish of her pencil. [53]

The only one of these three translations to depart significantly from the syntactic structure of the original is Nicolas Pasternak Slater's. He abandons the gradual layering of the sentences in favour of a rather clearer double short-long alternation.

Which of them is the best? It's a very subjective question. The smoothest to read is probably Haywood-Harari's. However, I agree with Christine Jakobson that Pasternak Slater's makes the best sense. The weakest of the three is Pevear-Volokhonsky's.

Though the actual difference, in this case, is pretty slight, it's also cumulative. If you want to savour the intricacies of this long novel by one of Russia's greatest poets, you should definitely try to find a copy of Nicolas Pasternak Slater's new translation. If, however, you just want a quick read, then Hayward-Harari's still reads surprisingly satisfactorily after all these years.

Perhaps, as in the case of Constance Garnett, that's because it's contemporary with the novel itself: written from a similar sensibility, in that, now, long-ago era when every piece of 'dissident' literature from Russia was guaranteed an immediate sale to lovers of freedom of speech everywhere. The actual quality of the books in question - widely variable, alas - was of far less consequence.

•

Leonid Pasternak: Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak

Leonid Pasternak: Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak

(1890-1960)

Poetry:

- Пастернак, Борис. Стихотворения и Поэмы. 1976. Библиотека Поэта. Ленинград: Ленинградское отделение, 1977.

- Pasternak, Boris. Поэзия: Стихотворения / Поэмы / Переводы. Екатеринбург: У-Фактория, 2003.

- Pasternak, Boris. Poems 1955-1959. 1959. Trans. Michael Harari. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1960.

- Pasternak, Boris. In the Interlude: Poems 1945-1960. Trans. Henry Kamen. Foreword by Sir Maurice Bowra. Notes by George Katkov. Oxford Paperbacks. London: Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Pasternak, Boris. Poems. Trans. Lydia Pasternak Slater. 1963. Unwin Paperbacks. London: George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., 1984.

- Pasternak, Boris. Selected Poems. Trans. Jon Stallworthy & Peter France. 1983. The Penguin Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984.

- Pasternak, Boris. Prose & Poems. Revised Edition. Ed. Stefan Schimanski. Trans. Beatrice Scott, Robert Payne & J. M. Cohen. Introduction by J. M. Cohen. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1959.

- Pasternak, Boris. The Poems of Doctor Zhivago. 1957. Trans Eugene M. Kayden. Introduction by James Morgan. Illustrated by Bill Greer. Hallmark Crown Editions. Kansas City, Missouri: Hallmark Cards, Inc., 1971.

Prose:

- Pasternak, Boris. The Collected Prose Works. Ed. Stefan Schimanski. Russian Literature Library. London: Lindsay Drummond Ltd., 1945.

- Pasternak, Boris. Safe Conduct: An Early Autobiography and Other Works. Trans. Alec Brown / Five Lyric Poems. Trans. Lydia Pasternak-Slater. 1958. London: Elek Books Limited / Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1959.

- Pasternak, Boris. The Voice of Prose. Volume One: Early Prose and Autobiography. Ed. Christopher Barnes. Polygon Russian Series. Edinburgh: Polygon Books, 1986.

- Pasternak, Boris. The Last Summer. 1934. Trans. George Reavey. London: Peter Owen Limited, 1959.

- Pasternak, Boris. The Last Summer. 1934. Trans. George Reavey. 1959. Introduction by Lydia Slater. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961.

- Пастернак, Борис. Доктор Живаго. 1957. Milano: Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, 1961.

- Doctor Zhivago. 1957. Trans. Max Hayward & Manya Harari. 1958. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1959.

- Doctor Zhivago. 1957. Trans Max Hayward & Manya Harari. 1958. Fontana Modern Novels. London: Collins Fontana, 1974.

- Robert Bolt. Doctor Zhivago: The Screenplay. Based on the Novel by Boris Pasternak. 1958. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1965.

- An Essay in Autobiography. 1959. Trans. Manya Harari. Introduction by Edward Crankshaw. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1959.

Plays:

- Pasternak, Boris. The Blind Beauty: A Play. 1960. Trans. Max Hayward & Manya Harari. Foreword by Max Hayward. A Helen and Kurt Wolff Book. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1969.

Letters:

- Pasternak, Boris. Letters to Georgian Friends. 1967. Trans. David Magarshack. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

- Mossman, Elliott, ed. The Correspondence of Boris Pasternak with Olga Freidenberg. 1981. Trans. Elliott Mossman & Margaret Wettlin. A Helen and Kurt Wolff Book. New York & London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, Inc. 1982.

- Pasternak, Boris, Marina Tsvetayeva & Rainer Maria Rilke. Letters Summer 1926. 1983. Ed. Evgeny Pasternak, Elena Pasternak & Konstantin M. Azadovsky. Trans. Margaret Wettlin & Walter Arndt. 1985. Oxford Letters & Memoirs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Secondary:

- Bradshaw, Jennifer, trans. The Memoirs of Leonid Pasternak. 1975. Introduction by Josephine Pasternak. London: Quartet Books Limited, 1982.

- Carlisle, Olga. Poets on Street Corners: Portraits of Fifteen Russian Poets. New York: Random House, 1968.

- Davie, Donald, & Angela Livingstone, ed. Pasternak. With Verse Translations by Donald Davie. Modern Judgements. Ed. P. N. Furbank. London: Macmillan and Co Ltd, 1969.

- De Mallac, Guy. Boris Pasternak: His Life and Art. 1981. London: Souvenir Press, 1983.

- Finn, Peter, & Petra Couvée. The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle over a Forbidden Book. 2014. Harvill Secker. London: Random House, 2014.

- Gifford, Henry. Pasternak: A Critical Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

- Gladkov, Alexander. Meetings with Pasternak: A Memoir. 1973. Trans. & ed. Max Hayward. London: Collins and Harvill Press, 1977.

- Hingley, Ronald. Nightingale Fever: Russian poets in Revolution. New York: New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981.

- Hingley, Ronald. Pasternak: A Biography. London: George Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd., 1983.

- Ivinskaya, Olga. A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak. The Memoirs of Olga Ivinskaya. 1978. Trans. Max Hayward. 1978. Fontana / Collins. London: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1979.

- Mandelstam, Nadezhda. Hope Against Hope. Trans. Max Hayward. Introduction by Clarence Brown. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Mandelstam, Nadezhda. Hope Abandoned: A Memoir. 1972. Trans. Max Hayward. 1973. London: Collins & Harvill Press, 1974.

- Pasternak, Evgeny. Boris Pasternak: The Tragic Years, 1930-60. Trans. Michael Duncan. Poetry trans. Craig Raine & Ann Pasternak Slater. 1990. London: Collins Harvill, 1991.

- Payne, Robert. The Three Worlds of Boris Pasternak. 1961. London: Robert Hale Limited, 1962.

- Raine, Craig. History: The Home Movie. London: Penguin, 1994.