I've spent a good deal of time these summer holidays rereading books by Thomas Mann. When I wasn't reading him, I was writing blogposts about him: on this site as well as my bibliography one. And when I wasn't reading or writing about him, I was ordering new items to fill (mostly imaginary) gaps in my Mann collection. I may have gone a bit over the top in that respect, in fact.

Even so, it came as a surprise when I saw how many of the people I mentioned him to already seemed to have a pretty comprehensive knowledge of the life and times of Thomas Mann. I hadn't realised his work was so much in the mainstream. Until the penny dropped. Their knowledge was not so much knowledge gleaned from reading Mann, as a reflection of the vogue of Colm Tóibín's recent biographical novel The Magician.

So what's wrong with that, you ask? Why, nothing at all. There's no reason why people shouldn't use biographies and even biographical novels to pick up information about authors they've never actually read. I've done it myself, and feel no compunction in admitting the fact.

It isn't quite the same as actually reading your way through Buddenbrooks or The Magic Mountain, mind you, but then who ever claimed it was? I guess any disquiet I feel over this - which I freely admit may be partially motivated by pique: there I was thinking I was something special because I'd ploughed through all these immense novels by some obscure old German, only to find that all his secrets were freely on sale in a far more convenient and readable form - is really based on a couple of other issues.

My first concern can be outlined more or less as follows. The Magician is certainly a very readable novel, but is it a good novel? There seems to be a kind of concensus among those who haven't actually read Mann that it is a pretty good novel - even such terms as 'masterpiece' have been bandied about (with a subtle implication that Mann is rather lucky that one so gifted should take him up at this late date in time).

I, too, think it a good novel: or at any rate a very entertaining one, which is perhaps not quite the same thing. But then I'm rather a fan of bio-fiction. In my teens I greatly enjoyed reading fat tomes by the likes of Irving Stone which gave overviews of the lives of worthies like Vincent Van Gogh (Lust for Life) or Michelangelo (The Agony and the Ecstasy) long before I'd seen the fine films based on these books.

I've provided a list of Irving Stone's books at the bottom of this post for anyone who'd like to follow up on his work. His later books on the likes of Darwin and Freud were perhaps less successful than the earlier ones, but there's no harm in such works (I think), especially given the lack of pretentiousness which surrounds them.

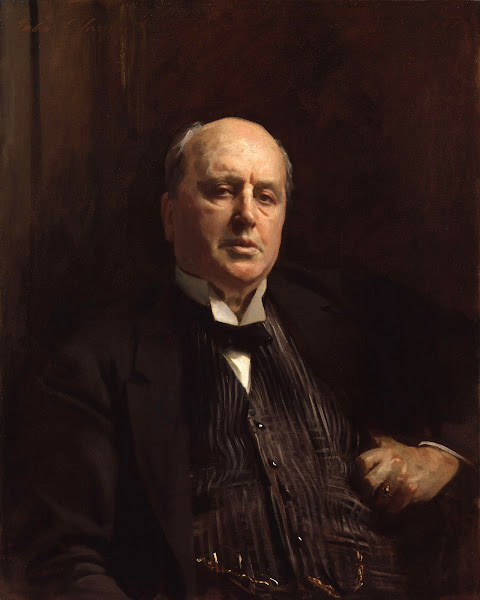

That isn't quite the tone people take when they talk of Colm Tóibín. After all, he's only written two such novels so far - about, respectively, Mann and Henry James - but he does appear to have won quite a reputation as a serious modern author with his (many) other novels.

The Henry James novel, which I've also read, is interesting. Tóibín makes a concerted attempt to inhabit the style as well as the consciousness of James during one of the great crises of his life, the failure of his dramatic ambitions in the 1890s. It's a far more focussed, and perhaps more ambitious attempt to become the Master, than is his Mann.

On the other hand, the Mann book covers a whole half-century of his life and contacts in a series of neatly staged scenes, with an overarching theme. Such a task cannot have been easy. It might, in fact, have been easier to repeat his earlier success by doing a study of some particular aspect of his life in a prose-style pastiched from Death in Venice.

Which brings me to my second point. No-one's ever really been in any serious doubt about the homoerotic inclinations of either Henry James or Thomas Mann. True, the former may well never had had sex at all in the conventional sense. He certainly formed no longterm relationships, and kept his private life a well-guarded secret.

Mann, by contrast, was a married man, with a complex and turbulent family life, and a crowd of children and siblings who all seem to have been in varying states of rebellion at various times. But no reader of his work can fail to notice his obsession with male beauty and passionate same-sex friendships. Even if you didn't, critics and biographers have pointed it out ad nauseam. But did he ever actually have sex with a man? No-one knows. There are reasons to doubt it.

Tóibín's Mann certainly does. He's a good deal gayer than any previous version of Mann - which is, again, Tóibín's prerogative. Nor does this decision exactly come as a surprise, given the tenor of his other work. His James, too, is far gayer than (say) Leon Edel's.

All that is certainly well within the bounds of fair comment. But Tóibín's Mann is also far more of a domestic tyrant and family autocrat than seems to come through in his surviving letters and diary - not to mention a bit of a sneak when it comes to hiding his rather hole-in-corner affairs.

There's a very apposite letter by Thomas Hardy once applied by the poet Elizabeth Bishop to a not dissimilar case:

Here is a quotation from dear little Hardy which I copied out years ago ... It's from a letter written in 1911, referring to "an abuse which was said to have occurred - that of publishing details of a lately deceased man's life under the guise of a novel, with assurances of truth scattered in the newspapers." ...Which I guess is my point. 'If any statements in the dress of fiction are covertly hinted to be fact, all must be fact, and nothing else but fact, for obvious reasons.' In other words, interesting though many of Tóibín's conjectures about Mann certainly are, it's hard to know how to take them, exactly, without any real sense of the evidence they're based on.

"What should certainly be protested against, in cases where there is no authorisation, is the mixing of fact and fiction in unknown proportions. Infinite mischief would lie in that. If any statements in the dress of fiction are covertly hinted to be fact, all must be fact, and nothing else but fact, for obvious reasons. The power of getting lies believed about people through that channel after they are dead, by stirring in a few truths, is a horror to contemplate."

Of course this could be used as a way of dismissing biographical novels in general as a viable literary form, but I'm not sure that it's necessary to go quite so far as that. Tóibín's novel strikes me - from my own knowledge of Mann's writing and from reading at least some of the other biographies - as unreasonably critical of his subject's bona fides in matters of the heart. He leaves Mann's rather more patchy political record largely to one side.

But all this leaves me dying to know where Tóibín got his information from. Out of his own head? Or are there substantive archives of material which give a sound basis for at least some of these suppositions? I don't suppose we'll ever know, unless he decides to give us a 'writing-of' book along the lines of Mann's own Story of a Novel, about the composition of Doctor Faustus; or David Lodge's The Year of Henry James, which gives an account both of his own James bio-novel Author, Author, but also of the various others - including Tóibín's - which appeared in that same year, 2004.

That's about as far as I'd got when I chanced upon a recent New Yorker article called "Thomas Mann’s Brush with Darkness" by their learned Germanophile music critic, Alex Ross. This was the first passage that caught my eye:

Because I have been almost unhealthily obsessed with Mann’s writing since the age of eighteen, I may be ill-equipped to win over skeptics, but I know why I return to it year after year. Mann is, first, a supremely gifted storyteller, adept at the slow windup and the rapid turn of the screw. He is a solemn trickster who is never altogether earnest about anything, especially his own grand Goethean persona. At the heart of his labyrinth are scenes of emotional chaos, episodes of philosophical delirium, intimations of inhuman coldness. His politics traverse the twentieth-century spectrum, ricochetting from right to left. His sexuality is an exhibitionistic enigma. In life and work alike, his contradictions are pressed together like layers in metamorphic rock.Yep. What he said. I know what he means when he refers to his Mannophilia as an 'unhealthy obsession.' As a fellow-obsessive, I also understand the reservations he mentions below on the actual need for Tóibín’s project:

At first glance, Tóibín’s undertaking seems superfluous, since there are already a number of great novels about Thomas Mann, and they have the advantage of being by Thomas Mann. Few writers of fiction have so relentlessly incorporated their own experiences into their work. Hanno Buddenbrook, the proud, hurt boy who improvises Wagnerian fantasies on the piano; Tonio Kröger, the proud, hurt young writer who sacrifices his life for his art; Prince Klaus Heinrich, the hero of Royal Highness, who rigidly performs his duties; Gustav von Aschenbach, the hidebound literary celebrity who loses his mind to a boy on a Venice beach; Mut-em-enet, Potiphar’s wife, who falls desperately in love with the handsome Israelite Joseph; the confidence man Felix Krull, who fools people into thinking he is more impressive than he is; the Faustian composer Adrian Leverkühn, who is compared to “an abyss into which the feelings others expressed for him vanished soundlessly without a trace” — all are avatars of the author, sometimes channelling his letters and diaries.He, too, feels some misgivings about the clash between Tóibín's imaginings and the existing documents:

Tóibín doesn’t adhere exclusively to the biographical record, and his most decisive intervention comes in the realm of sex. In all likelihood, Mann never engaged in anything resembling what contemporary sensibilities would classify as gay sex. His diaries are reliable in factual matters and do not shy away from embarrassing details; we hear about erections, masturbation, nocturnal emissions. But he clearly has trouble even picturing male-on-male action, let alone participating in it. When, in 1950, he reads Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar, he asks himself, “How can one sleep with gentlemen?” The Mann of The Magician, by contrast, is allowed to have several same-sex encounters, though the details remain vague.In the end, much though he relishes certain passages and aperçus in Tóibín's novel:

The Magician, deft and diligent as it is, ultimately diminishes the imperial strangeness of Mann’s nature. He comes across as a familiar, somewhat pitiable creature — a closeted man who occasionally gives in to his desires. The real Mann never gave in to his desires, but he also never really hid them. Gay themes surfaced in his writing almost from the start, and he made clear that his stories were autobiographical. When, in 1931, he received a newspaper questionnaire asking about his “first love,” he replied, in essence, “Read ‘Tonio Kröger.’ ” Likewise, of Death in Venice he wrote, “Nothing is invented.” Gay men saw the author as one of their own ...Perhaps the real problem with The Magician, then, is that its author is not content to write a solid, unexciting Mann-and-water bio-novel in the Irving Stone mode, but isn't ready, either, to engage fully with the 'element of charlatanism' (Alex Ross's phrase) inherent in Mann's magpie methodology.

As a result, The Magician ends up falling between two stools. It provides a fascinating (though selective) reading of Thomas Mann's life, but not really of his art. Tóibín's muse seems more comfortable with the stylistic conventions of Henry James's day than with the oncoming juggernaut of twentieth-century Modernism. Mann's basic techniques of irony and sampling were foundational for post-modern writers such as Nabokov or Pynchon. Mann, after all, 'had always been haunted by the sense of being an empty shell, a wooden soldier.'

All along, the dubiousness of genius had been one of his chief motifs. In “The Brother,” his essay on Hitler, he wrote that greatness was an aesthetic rather than an ethical phenomenon, meaning that Nazi exploitation of Goethe and Beethoven was less a betrayal of German artist-worship than a grotesque extension of it. The Magician’s finest trick was to dismantle the pretensions of genius while preserving his own lofty stature. The feat could be accomplished only once, and it happens definitively in Doctor Faustus, when Leverkühn’s explication of his valedictory cantata spirals into madness. An immaculately turned-out personification of bourgeois culture stages its destruction.So am I saying that you shouldn't read The Magician? Not at all. Tóibín is not alone nowadays in his return to the solider conventions of the realist novel. What I would advise, though, is tempering your reading of Tóibín with some study of Thomas Mann's own fiction: even just a few short stories if you don't have the patience for one of the novels. "Disorder and Early Sorrow" or "Mario and the Magician" will quickly convince you, if you needed the reminder, that we're not dealing here with an empty windbag but with a far subtler talent, a writer on a level with Chekhov or Joyce.

-

Fiction:

- Lust for Life: A Novel of Vincent Van Gogh. 1935. London: John Lane / The Bodley Head, 1940.

- Sailor on Horseback. [Jack London] (1938)

- Immortal Wife. [Jessie Benton Frémont] (1944)

- Adversary in the House. [Eugene V. Debs and his wife Kate] (1947)

- The Passionate Journey. [American artist John Noble] (1949)

- The President's Lady. [Andrew Jackson and Rachel Donelson Jackson] (1951)

- Love is Eternal. [Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd] (1954)

- The Agony and the Ecstasy: A Biographical Novel of Michelangelo. 1961. Fontana Books. London: Collins Clear-Type Press, 1965.

- Those Who Love. [John Adams and Abigail Adams] (1965)

- The Passions of the Mind. [Sigmund Freud] (1971)

- The Greek Treasure. [Heinrich Schliemann] (1975)

- The Origin. [Charles Darwin] (1980)

- Depths of Glory. [Camille Pissarro] (1985)

- Clarence Darrow for the Defence. 1941. London: The Bodley Head, 1949.

- They Also Ran. [Failed Presidential Candidates] (1943 / 1966)

- Earl Warren (1948)

- Men to Match My Mountains: The Monumental Saga of the Winning of America's Far West (1956)

- [with Jean Stone]. Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent van Gogh. 1937. London: Cassell, 1973.

- [with Jean Stone]. I, Michelangelo, Sculptor: An Autobiography through Letters. Trans. Charles Speroni. 1963. Fontana Books. London: Collins Clear-Type Press, 1965.

Non-fiction:

Edited: