'Everyone should be noted' is the last line of the Acknowledgments at the back of Auckland poet Richard Taylor's latest book, The Secret of Being Unpopular.

This post isn't really meant as a formal review of his work - he is, after all, large, he contains multitudes - but more as a few comments, combined with reminiscences.

I've capped it off with two email interviews, one with Richard and the other with his son Victor, who's also just published a collection of poems, his first, entitled Rift.

I've known Richard Taylor for nearly thirty years. We first met at Poetry Live, the weekly poetry reading / performance roadshow which has been migrating from bar to bar around Auckland's K. Rd for the last several decades. We were both friends with the late Rev. Leicester Kyle, and he might be said to have introduced us.

How shall sum up Richard? He can be quite a disconcerting person to meet for the first time. While immensely erudite and well-read, he doesn't exactly project a bookish demeanour. No, there's something more Rabelaisian about him than that: someone who loves food and drink and witty conversation - and is sometimes a little the worse for wear.

The freeflowing allusiveness of his talk is certainly not for the uptight, either. There have been some face-offs over the years - never (that I can recall) between Richard and me, but between him and others of the thinskinned poetry tribe.

Richard's mind is never asleep. He always pursues his own bent. I recall some of his experiments with photography and typography on his marvellous blog Eyelight (2005- ) - long treks over fields of associative imagery, which must have taken forever to construct, but which seem as anarchic and fluid as Walt Whitman's dithyrambic diatribes must have been to readers in the 1850s.

This dizzying sense of multiplying associations comes through in his prose, too. When, in the past, as a magazine editor, I commissioned pieces from Richard, I found that a little compression and tidying did have the effect of burnishing the power and originality of his ideas. But I also knew I was normalising them - attempting to obscure the particularity of the personality behind this mode of discourse.

He's not one of those law-giving critics people fear: a Belinsky, or an Edmund Wilson, whose verdicts can make or break a career. Richard belongs more to the side of the accommodating and celebratory: a Coleridge, or a Harold Bloom, wearing his idiosyncracies on his sleeve. He reads so much! Richard's always under the spell of some book or other, and he's combined all these years of apparently random text-sampling into an immensely powerful lens of critical insight.

There was a rather studied elegance to his previous book Conversation with a Stone. Now, as I glance through it, I can admire the ways in which Richard's anarchic muse has been kept in bounds (if not wholly tamed) by a clear layout with lots of white space around the lines. Is it quite him, though? The appearance of this book also spurred him to start a new blog: Richard, You MUST try to be more focused - (2012- ) - a quote (apparently) from one of his university tutors way back when - which continues to partner, but not supplant, his older site Eyelight.

For me, part of the interest of this new book is that it represents Richard's version of Richard, rather than that of a well-meaning editor or publisher. It's far closer to the true comprehensiveness of his vision (insofar as that's possible in the print medium).

I guess everybody knows the story of the death of Chatterton - both the suicide of the starving young poet ("marvellous boy", as Wordsworth called him), and the strange story of the commemorative painting above, by Pre-Raphaelite artist Henry Wallis.

The young poet and novelist George Meredith agreed to pose for the picture, as Wallis was a friend of his brother-in-law. To compound this chain of connections, Meredith's wife Mary Ellen eloped with Wallis shortly after the picture had been exhibited at the Royal Academy, and the two fled together to Capri.

"Richard Taylor's book's title and title poem The Secret of Being Unpopular's title was inspired by a strange review of George Meredith", he informs us on the back-cover blurb of his book. So just why was George Meredith so unpopular? Wikipedia informs us that:

His style, in both poetry and prose, was noted for its syntactic complexity; Oscar Wilde likened it to "chaos illumined by brilliant flashes of lightning".There's more to it than that, though. His fame as a poet is based mainly on the sonnet sequence Modern Love (1862), "a sequence of fifty 16-line sonnets about the failure of a marriage, an episodic verse narrative that has been described as 'a novella in verse'." This sequence, while not directly autobiographical, was clearly inspired by his own experience of being abandoned by Mary Ellen. The impulse to write it came from her lonely death in 1861 - though neither Meredith nor her ex-lover Wallis nor her father Thomas Love Peacock, another well-known poet and novelist, deigned to attend the funeral.

The bitterness and disillusionment fostered by these early experiences informed almost all of Meredith's subsequent work. It has been argued, in fact, that his style grew more complex and convoluted in direct response to the public demand for further romans-à-clef from him. Only those works of his which seemed to have clear parallels in contemporary scandal achieved more than a succès d'estime.

Can one see in all this certain resemblances to Richard Taylor's own "chaos illumined by brilliant flashes of lightning"? You never know just what will come up in a Taylor poem or prose-piece - that is, if there really is much of a difference between the two genres for him.

Meredith's work, too, tends to be more honoured in the breach than the observance - his public, now, tends to be made up predominantly of literature professors. But Modern Love, in particular, is a very powerful poem indeed. As - for that matter - is that long title-piece of Richard's, "The Secret of Being Unpopular." If you're serious about learning more about the nature of Richard's work, this is probably the best place to start.

One thing's for certain: you'll be opening up a new and unaccustomed world for yourself if you do so.

Richard Taylor has written of his son Victor's book:

For a father and son to publish poetry or anything else at the same time is very unusual and means there is surely hope for, not only human life (despite the many trials we are all subject to) but culture and creativity.For, "while at times a philosophical pessimist," Richard says he "cannot help being a living and day by day optimist, except perhaps on a cold dreary morning before breakfast!"

I myself am writing this on just such a morning - cold and dreary, with a driving rain coming in from the sea - but I have had breakfast, so let's continue.

I have a (probably bad) habit of starting to read poetry collections at the back, with the last poem, then dipping a tentative toe into the middle and leafing around a little before ever venturing to turn to the front.

In the case of Rift, this led me straight to a poem called "Star of south":

They call this university "an institution of learning". I sit with kateI like that. I like it a lot. I like the picture it paints: the sparrows, the students, the pomposity of this shabby old "institution of learning". What I like particularly, though, is the absence of fine writing or pretentious word choices in the descriptions. The sparrows "jump along" - they don't hop or frisk or congregate or anything else of that sort. And then one of them "leaps up" - rather than nuzzling or pecking or fluttering. Simple and to the point.

edger in her block. The sparrows chirp, I feed them, I watch them

jump along; young students walk by. I sit and watch sparrows.

One leaps up and takes bread from my hand - back to his friends.

We then get a profusion of imagery suggested by a young lady descending a nearby set of stairs, absurdly hymned and idealised with full Keatsian exuberance through four full stanzas, until, again, the poet comes back down to earth:

Apart from that, not much happens in the kate edger block, or toIn form, this is clearly reminiscent of a Frank O'Hara "I do this, I do that" poem: the use of first person and present tense, accompanied by a kind of appositional irony.

kate edger or the block. I will just keep feeding sparrows, watching

students, or maybe I will go to the bookshop. think up another

poem, short or prose. I could unleash four elements of multiple

patterns from all seven realms, circle earth, tap into ley-lines -

create a world of gold pyramids and bronze shine a pale sheen.

And, as with Frank O'Hara's work, there's a delightful insouciance about it. O'Hara had to learn to curb his original surrealist urge and counterpoint it with more quotidian details. Victor, too, seems to have discovered how to retain portions of his more florid linguistic instincts by tempering them with the everyday. It's a splendid coda to his book.

Leafing back a few pages, I find "Golden horse":

Here is Jakey an autistic 15-year-old boy, he sits at his computerWell, I for one am hooked. I have to find out more of Jakey's story. I don't want to introduce any unnecessary spoilers, but I fear (like me) you already suspect that it will end badly.

playing computer games all day no one knows he exists except his

mother and his uncle; they all live in a rundown trailer park. "Be

quiet!" - His mother is opening the door to his room. "Shhhhhh!"

But Jakey already exists by the end of that first stanza. Victor's talent for characterisation and vivid narrative is perhaps the most notable thing about this first collection of his poetry to date. It's an unusual skill in a field so often dominated by imagery and autbiographical musings. And it bodes well for the future, I think.

"I’m also chipping away at Dracula," says Victor below, towards the end of his interview. I suspect that the reason this comment interests me is not simply because of my obsession with Bram Stoker, Sheridan Le Fanu, M. R. James, and other writers of gothic literature, but also because of the nature of the novel itself.

Readers who've come to the story by way of screen adaptations are often surprised by how complex and "intertextual" a novel Dracula is. It's made up of letters, diary entries, news reports - even transcripts of recordings made on wax cylinders: pretty dazzlingly innovative technology for the late 1890s.

In fact it could be argued that not only did this aspect of Stoker's narrative help to inspire steampunk, but its nature as a self-questioning artefact anticipates many of the innovations of the Nouveau roman of the 1950s.

I remark on it here because I think that it offers clues on how Victor might accommodate his taste for metaphysics with his undoubted talent for characterisation and narrative as he continues to develop as a writer.

If his father Richard exhibits a Walt Whitman-like taste for the vast and multifarious, sounding his "barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world", it might be said that it is Victor who more closely resembles George Meredith: not so much the syntactic complexity, but certainly the "chaos illumined by brilliant flashes of lightning."

How else could one characterise Jakey's story, this account of an "autistic 15-year-old boy" no one else knows exists?

I look forward to reading more by Victor in the future, while continuing to follow, with awe, Richard Taylor's fascinating, visionary, Blakean career.

- What are the strengths of your new book of poems, would you say?

- Why did you give it that title?

- What pleases you most about it?

- Is there anything about it that displeases you?

- Which people - writers, artists, musicians, or otherwise - have influenced you most?

- Joseph Campbell said "Follow your bliss" - what's your bliss?

- What are you reading at the moment? Poetry, or something else?

I think the mix of "voices" and a mix of an intuitive and 'planned' way of writing. Thus I have mixed older (in style) with more recent work. I have a kind of focus. However I use as can be seen a range of texts to point to various ideas. In a sense - except inside my poems - I am not saying anything in the long titular poem -- or I am taking a position that explores. Also the book in the early stages signals later works. Often the quotes are either myself, others or a mixture of ... This creates an eerie effect sometimes beautiful. I mix more obviously 'beautiful' poems with more densely 'written' or language based.

The title is from a review of Meredith as explained. Then it grew upon me that I am referring to myself. I think I am somehow and even want to be 'unpopular' but not in any radical way. I like the idea I have read almost nothing of Meredith but he seems to fascinate me and he evokes that review which in an essay on Meredith, Pritchett quotes, which I found out later ... It, the words of the review inspired me to write and I wrote that long poem very quickly. The other poems echo later poems and things in that long poem. Acker describes, in a way, my technique in the interview I quote. Bouvard and Pecuchet I love and they question forever! Thus I am a questioner ... Like Wittgenstein.

I like the mix of poems. At the moment I need to do some more copies and correct some errors. But poems such as my truck poem join in with say 'Humpty Empty Back Make' or 'Glass Swan'. Although I use references or hints to other works I avoid the Eliot-Pound obsession with the decline of culture. I like their methods but I would celebrate William Carlos Williams as much as Eliot or his Paterson and also Hart Crane's Bridge, or the spirit of it, and also Moore's quotes sometimes as with Williams of 'ordinary' things and people. Hence both my father and mother talk in the poems as does the tramp in Gavin Bryars 'Jesus Christ never...' and there is a Maori Tohunga saying things we might not agree with but there he was, then my early story based on working in the freezing works (published) in Mate a long time ago, is there and some of a dramatic 'Shakespearean' poem mixes with my early paen to (it was my father and father-in law's death and so on. When I read the long poem or poems I find things that seem new each time.

I always feel limited by a single medium. I wanted, but couldn't afford at the time, many images, colours, font changes and much much more in the book and the text esp. the long poem. I am also a bit unfair calling Einstein 'Deathstein' but it was Leo Szilard (invented and patented (!) the chain reaction) who persuaded E. to write a letter to Roosevelt. Hence the Manhattan (Richard Rhodes The Making of the Atomic Bomb. I read this way before this film re Oppenheimer or Oppenhimmel.) But like Wittgenstein I think science and technology have been too highly lifted up into the light - this is something he felt during and after WWII and I feel this. But how to show my interest in philosophy and avoid something someone has seen in a movie and so on? There are poems in the first two parts I might have replaced but overall I feel I have a sufficient mix. I am trying to avoid one 'style'... perhaps influenced, say, by Barthes' Writing Degree Zero but also the idea to play, mix things, take a chance. The "bad" poems are always there. [Of course there are also typos etc but I am thinking of leaving them all in!] Ashbery and Sylvia Plath were two poets who in different ways were also important to me as Eliot was and still is given my wariness of him and Pound's obsessions ... Also Auden and some of the French symbolists et al ...

I think that as a teenager all the usual Romantic poets, Shakespeare, Eliot, certain artists (all art interests me) and many novelists. Also my reading of Gerald Durrell, and the Scientific Book Club Books, and much else. Lewis Carroll, R A K Mason, and much else. But more recently from about 1988 or so. Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man, and later Oliver Sacks, but I read for years a lot of John Ashbery's poetry, but also the US Language Poets, Stein somewhat, Beckett, Auden when I was a teenager but I still quote him and many others. Wordsworth and Keats, Coleridge but there are many modern poets in NZ also, and elsewhere. I like writers like Donald Barthelme and Kafka and Richard Brautigan, Rilke. Possibly Ted Berrigan and Berryman. It is accumulative as I am 'always reading'!

I wasn't sure who Campbell was. I would say it is reading but also being and being healthy in the world. Also learning but added to that a proviso like the narrator in Ford's The Sportswriter I like also to not know some things. The myths etc I invent myself as if talking to myself. I like Ovid's Metamorphosis rather than Dante. One bliss was reading The Brothers Karamazov more recently. In the world, just being, seeing beautiful things and trees and flowers or experiencing beautiful or interesting ideas and word combinations. The general phenomena of this world. No great fixed ideas.

I am reading one of the diaries of Anne Truitt, an artist I hadn't known until I read her first book. Also I read some of Stein's 'Stanzas in Meditation', some Keats, but I like what to me is the comedy of Beckett so decided to read his trilogy Molloy, Malone Dies, and the Unnamable. I read widely but I read fairly recently Carson McCullers' The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. She was indeed a great writer.

•

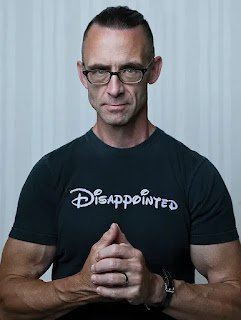

Janet Robin: Richard & Victor Taylor at a Protest (2012)

Janet Robin: Richard & Victor Taylor at a Protest (2012)'Pepperoni Pizzas & Metaphysical Ideas':

Seven Questions with Victor Taylor

- What are the strengths of your new book of poems, would you say?

- Why did you give it that title?

- What pleases you most about it?

- Is there anything about it that displeases you?

- Which people - writers, artists, musicians, or otherwise - have influenced you most?

- Joseph Campbell said "Follow your bliss" - what's your bliss?

- What are you reading at the moment? Poetry, or something else?

I’d say the main strength of my book lies in the variety of forms. The idea is to further separate and isolate each poem from the others. Every poem exists in its own spiritual domain — they don’t link up or form a narrative chain. This means the reader is encountering something entirely new with each piece.

There is a similarity, however, in the metaphysical ideas. Many of the poems are surreal and transcendent, so the central strength is really in the images themselves.

Well, I played around with a few names — VAST, VOID, and some other more extravagant ones. RIFT felt simpler, perhaps more neutral. A rift means a break, split, or crack in something, and one of my goals is to break the reader’s perception of reality — to get them to question what is real. To me, dreams are just as real as waking reality.

RIFT may have been chosen unconsciously. Maybe I felt isolated, like there’s a rift between me and everything else. Maybe I should have called it I am in the rift.

This is my first book, and I’m really pleased with it. For one, it’s the best thing I’ve ever produced. I began my journey into poetry when my father encouraged me to start reading books. From there, I eventually started writing a few poems of my own. I fell in love with the art form — it felt like magic, which, in many ways, it is.

What pleases me most is being able to express all my visions and images through poetry. That, to me, is the greatest joy.

Nothing really displeases me about poetry itself — except perhaps the continuous wave of confessionalist poetry. At its height, particularly around 2022 and 2023, it felt like a dense cloud of pathological blackness. That trend became overwhelming. Recently, I noticed an new style of poetry I call “Encryptic” poetry - emerging in 2025.

Many people have influenced me. In the early days, I probably absorbed too much from others, which made it difficult to develop my own voice. That’s a common challenge when you’re starting out. But over time, with more experience, I’ve learned how to hold on to my own style while still drawing inspiration from others.

My dad — who’s a great poet — introduced me to many poets early on. I was especially drawn to the Romantic symbolists: Blake, Keats, Shelley. More recently, I’ve been reading Bob Kaufman, whose work offers a different kind of intensity and rhythm.

These days, with Facebook full of poetry groups and so many styles circulating, I think originality is more important than ever. I also have several friends who are poets, and being around them keeps me sharp and engaged with the craft.

Apart from pepperoni pizzas? Well — fantasy, and useless metaphysical ideas.

I’m currently reading American Literature, which I was introduced to through my university course at Massey. Some of the authors include Henry James, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, and many others. I’m also chipping away at Dracula.

Father's Day (July 6, 2018)

Father's Day (July 6, 2018)l-to-r: Finnegan, Ellery, Richard & Victor Taylor

Times like this make life worth living

- Richard Taylor

•