We were up in Orewa on Tuesday, enjoying the nice weather and trying to persuade ourselves that we were still on holiday. Part of the celebrations always include looking through any vintage and op shops that happen to present themselves: in this case the local Hospice Shop.

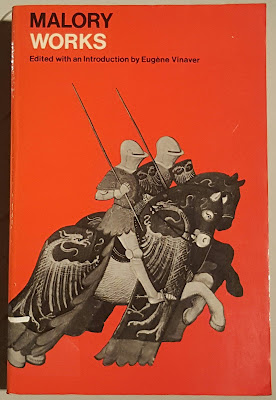

The more glamorous books were all up on the shelves, but there was a scruffy old sack labelled 'classics' to one side of them, and this is the one treasure I found in there, among all the old hymnbooks and school editions of Shakespeare and Wordsworth.

The dustjacket was a bit ripped, but the book was otherwise in fairly good nick, perhaps because it had once belonged to the Vice Consul of the United States, a certain Clarence J. McIntosh (he'd signed his name inside, as well as using an official stamp). It cost me one dollar.

So what's the attraction of this ancient, outmoded anthology of 'Modern Poetry'? it does, to be sure, constitute a kind of survey of how the field looked in 1938, but why should

that be of any particular interest?

Don't you just love that little picture of 'Random House' itself? There's a reassuring solidity about their books, as if they come from a world which still - however vaguely - made sense. It was, after all,

1938.

Here's what the blurb has to say:

The dominant note of this collection of modern poetry is excitement. Here all the rules of the conventional anthology are abandoned and the chief emphasis is given to the dynamic quality and content of present-day verse. Representative poems by the greatest epic and lyric poets of the past twenty-five years in America and England are included, as well as folk-songs of the Negro, acid light verse, modern humor and satire, choruses from the experimental theatre, and even the sound-track of the pioneer movies. The result is an anthology of extraordinary vigor.

Sounds pretty good, doesn't it? And the editor himself, Selden Rodman, appears to have had an interesting time of it - judging by his

wikipedia page, at any rate. He only died in 2002, having written a whole slew of books about Haiti, Latin America, poetry, and a range of other subjects.

Look again at that list of 'representative' poets on the cover, though:

Robinson Jeffers --

T. S. Eliot --

Edna St. Vincent Millay --

James Joyce --

Stephen Spender --

W. H. Auden --

D. H. Lawrence --

Robert Frost --

Hart Crane --

Dorothy Parker --

Paul Engle --

Vachel Lindsay --

Ezra Pound --

Carl Sandburg --

C. Day Lewis --

Archibald MacLeish --

Kenneth Fearing --

Stephen Vincent Benét --

Elinor Wylie --

John Masefield --

A. E. Housman --

Amy Lowell --

Josephine Johnson --

Bartolomeo Vanzetti --

William Butler Yeats --

Edwin Arlington Robinson --

Malcolm Cowley --

Horace Gregory --

Frederic Prokosch --

E. E. Cummings --

Wilfred Owen --

William Rose Benét --

Muriel Rukeyser --

Louis MacNeice --

Wallace Stevens --

AND OTHERS

Among the 'others' included in the anthology but not mentioned on the cover are: Marianne Moore (with two poems], and William Carlos Williams (with one). Imagine

not mentioning either of those two today!

All the British 'MacSpaunday poets' are there: Auden, Spender, MacNeice and Day Lewis, but not Hugh MacDiarmid (one poem) or Roy Campbell (also one).

There

is one New Zealander - or sort of: Lola Ridge (one poem). No Australians or Canadians have managed to sneak in, however.

That's no great insult, though - of the other Americans included, but not mentioned on the cover, we have Conrad Aiken, Edgar Lee Masters, John Crowe Ransom, and Allen Tate. Delmore Schwartz is the only one of the younger generation of poets who would come of age in the 40s (Robert Lowell, Robert Penn Warren, Kenneth Rexroth) to make it in.

I guess the real fascination for me is all those 'big names' (at the time) who have fallen almost entirely out of favour. The Benét brothers, Stephen and William, for instance - not to mention the latter's wife Eliinor Wylie. More of

her later. That craggy old misanthrope Robinson Jeffers - the almost equally gloomy East Coast equivalent Edwin Arlington Robinson. My old friend John Masefield. Edna St. Vincent Millay (though she

does seem to be making a bit of a comeback these days). Kenneth Fearing (who he?). What on earth is Vanzetti (of Sacco & Vanzetti fame) doing there?

I have a great affection for a number of these poets. Considerations of abstract merit - let alone 'importance' - seldom enter into my desultory poetry reading. I do love a long verse narrative, and a lot of these poets specialised in them.

In fact, so much did I enjoy reading the two Elinor Wylie poems included in here - I'd heard of her, but not really read her before - that I've gone off and ordered her collected poems

and collected prose - she wrote novels as well, it appears - on Amazon.com! If

that isn't Quixotic, I don't know what is.

Anyway, here's a more-or-less complete list of the entire table of contents (I couldn't be bothered writing out all of the titles of the poems included, but the actual authors are all here):

Part One

Marianne Moore, 'Poetry'

Thomas Hardy, 'Afterwards'

Lewis Carroll, 'Jabberwocky'

John Masefield, 'from Reynard the Fox'

A.E. Housman, [3 poems]

Walter De La Mare, 'The Listeners'

Robert Bridges, "Johannes Milton, Senex'

Rupert Brooke, [2 poems]

Elinor Wylie, 'Wild Peaches' & 'Castilian'

Edna St. Vincent Millay, 'Moriturus'

Robinson Jeffers, [3 poems]

James Joyce, 'I Hear an Army Charging upon the Land'

Dorothy Parker, [2 Poems]

Marianne Moore, 'The Monkeys'

D.H. Lawrence, [3 poems]

Arthur Guiterman, 'On the Vanity of Earthly Greatness'

Gerard Manley Hopkins, [4 poems]

Amy Lowell, 'Little Ivory Figures Pulled with String'

W.B. Yeats, [5 poems]

Part Two

Carl Sandburg, 'Who Can Make a Poem of the Depths of Weariness'

A Group of Negro Songs [8 poems]

W. C. Handy, [2 poems]

Edwin Markham, 'The Man with the Hoe'

Sarah N. Cleghorn, [2 poems]

Edgar Lee Masters, [3 poems]

Edwin Arlington Robinson, [3 poems]

Robert Frost, 'Two Tramps in Mud Time' & 'The Fear'

Vachel Lindsay, [6 poems]

William Rose Benét, 'Jesse James'

Bartolomeo Vanzetti, 'Last Speech to the Court'

Malcolm Cowley, [2 poems]

Lola Ridge, 'The Legion of Iron'

Stephen Vincent Benét, [2 poems]

Josephine W. Johnson, 'Final Autumn'

Roy Campbell, 'The Serf'

Paul Engle, 'from America Remembers'

Pare Lorentz, 'from The River'

Carl Sandburg, [4 poems]

Part Three

Archibald MacLeish, 'A Poem Should Be Palpable and Mute'

Ezra Pound, [3 poems]

E.E. Cummings, [5 poems]

T.S. Eliot, [4 poems]

Walter James Turner, 'In Time like Glass'

Wallace Stevens, 'Peter Quince at the Clavier' & 'The Mechanical Optimist'

Hart Crane, [6 poems]

John Crowe Ransom, 'Here Lies a Lady'

Conrad Aiken, 'Prelude LXI'

Allen Tate, 'Idiot'

James Palmer Wade, 'A Hymn to No One Body'

Archibald Fleming, [2 poems]

Horace Gregory, [2 poems]

E. B. White, 'I Paint What I See'

Frederic Prokosch, 'The Conspirators'

Archibald MacLeish, [6 poems]

Part Four

Kenneth Fearing, 'These Are the Live'

Wilfred Owen, [7 poems]

Kenneth Fearing, 'Dirge'

Louis MacNeice, [2 poems]

C. Day Lewis, [2 poems]

James Agee, [2 poems]

William Stephens, [2 poems]

Ogden Nash, [3 poems]

Stephen Spender, [5 poems]

William Carlos Williams, 'The Yachts'

Eunice Clark, [2 poems]

Alfred Hayes, 'The Death of the Craneman'

Selden Rodman, [2 poems]

W.H. Auden, [6 poems]

Edwin Rolfe, 'Definition'

Oscar Williams, [2 poems]

S. Funaroff, 'Of My Deep Hunger'

Hugh MacDiarmid, [2 poems]

Delmore Schwartz, 'For One Who Would Not Take His Life in His Hands'

Muriel Rukeyser, [6 poems]

One of the most fascinating things about this list is to compare it with the contents of the second, postwar (1946), edition of the anthology. There were a lot of additions (as well as a few subtractions - Rupert Brooke has gone, but then so has Wilfred Owen). Here are the newbies:

Robert Graves --

Louise Bogan --

Siegfried Sassoon --

Kay Boyle --

Thomas Wolfe --

Reuel Denney --

Babette Deutsch --

Mark Van Doren --

Edith Sitwell --

Jean Garrigue --

Ruth Pitter --

John Peale Bishop --

Edmund Wilson --

Robert Penn Warren --

John Wheelwright --

R. P. Blackmur --

Kenneth Rexroth --

William Empson --

Jose Garcia Villa --

Robert Fitzgerald --

Kenneth Patchen --

Dylan Thomas --

George Barker --

Dunsten Thompson --

Ralph Gustafson --

Lawrence Durrell --

Roy Fuller --

Ruth Herschberger --

William Abrahams --

Sagittarius --

Laurie Lee --

William Meredith --

Randall Jarrell --

Hubert Creekmore --

Alun Lewis --

John Manifold --

Sidney Keyes --

John Betjeman --

Robert Lowell --

Demetrios Capetanakis --

Thomas Merton --

Karl Shapiro

One thing you can't fault Rodman on is his industry. He was determined to keep up. His prescience in selecting Robert Lowell and Thomas Merton among the new American poets is impressive. For the rest, his selection of WWII poets (Alun Lewis, Sidney Keyes) isn't bad, considering how little time there had been to process the verse of the war years. No Dylan Thomas, no Keith Douglas, but I suspect that just shows that it took a bit of time for their merits to filter through.

Rodman attempts some knotty questions - 'Is Modern Poetry Difficult?' - in his preface (as well as 'What Makes it Obscure?' and 'Does Propaganda cancel It?') All in all, there's a pleasing New Deal optimism about his view of the future:

Our younger poets have taken the first step. They are beginning, as I believe the last part of this anthology will indicate, to fuse the naturalistic and symbolic in a new synthesis. They know that neither science nor sociology can be rejected. (45)

Well, bully for them! He goes on to explain that:

Poetry is the greatest of the arts because everyone can - and does - practise it. The ad-man and the gag-man, the housewife and the corner-grocer are latent poets.

But then he goes and spoils it all by saying, in his next sentence: 'Especially is the poetry of Carl Sandburg great for this reason.' Hmmm. Dunno about that. Rodman's touching faith in this idea of recording 'the poetry in the common speech, attitudes and aspirations of the people' culminates in his claim that:

That is why we have the paradox of the most original and indigenous American art in the anonymous outpourings of the oppressed Negro. That is why I have included the words of some of their songs. (45-46)

I guess our alarm bells may be ringing at this point in his argument. There's something so smug and patronising about that use of the word "outpourings' rather than simply 'songs' (or 'poems', for that matter). For its time, though, I think this decision of Rodman's was a brave one. It certainly attracted a good deal of attention, and (as it turned out) was the beginning of a lifetime's interest in the folk art of the Caribbean and elsewhere.

The question of

tone when one is exploring the polemical writing of the past is a tricky one. On the one hand he clearly distinguishes these 'outpourings' from the consciously crafted poems of the other authors - there is no Langston Hughes in either the 1938 or 1946 versions of his anthology, for instance.

On the other hand, there's little doubt that Rodman is sincerely moved, and sincerely admiring of these great songs - as indeed we are today - so perhaps we can cut him a bit of slack, and try and avoid what E. P. Thompson once called the 'enormous condescension of posterity.'

All in all, pretty good value for one buck, I'd say!