It's just very hard to think about anything else at the moment. New Zealand went into full COVID-19 lockdown on Wednesday night (25th March 2020, for the history books), and everyone immediately started broadcasting their impressions of the event, starting new blogs to record their daily thoughts, and (so we're reliably informed) working on their long-deferred novels.

There's nothing very original about this list, then, but it does include the main 'plague' books I've read and been impressed by over the last few years. It's bound to be a burgeoning genre over the next wee while, and it's generally a good idea to go back to your roots before launching your own raid on the inarticulate.

The fact is, epidemics are generally quite boring to read about. Once you've got past detailing the symptoms and totting up the ever-mounting grim statistics of dead and dying, you really have to do something quite original with your narrative to make it at all memorable. Each of the books below have succeeded in doing that, I think.

- Giovanni Boccaccio: Il Decameron (1353)

- Albert Camus: La Peste (1947)

- Daniel Defoe: A Journal of the Plague Year (1722)

- Horton Foote: 1918 (1985)

- Stephen King: The Stand (1978 / 1990)

- William Rosen: Justinian's Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Birth of Europe (2006)

- Randy Shilts: And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic (1987)

- Thucydides: The Peloponnesian War - Book 2: The Plague of Athens (430-426 BCE)

- Barbara Tuchman: A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (1978)

- Philip Ziegler: The Black Death (1969)

Of course it's rather difficult to define just what precisely a pandemic classic is. If it were simply a matter of writing about confinement and hardship - as in a siege (often accompanied by disease, after all) - I would go immediately to Lidiya Ginzburg's magisterial account of the 1,000-day siege of Leningrad during the Second World War:

Lidiya Ginzburg. Blockade Diary. 1984. Trans. Alan Myers. Introduction by Aleksandr Kushner. London: The Harvill Press, 1995.

I have, in any case, written about this book before. A long time ago I put together a couple of imaginary online courses intended to serve as background for a novella in my 2010 collection Kingdom of Alt. The second of these was called "Crisis Diaries," and still subsists on the internet somewhere. It includes a range of diaries kept under the stress of various crises, including siege, plague, civil war, addiction and other forms of personal and political turmoil.

I suppose, then, that I define a pandemic text by virtue of its focus on the nature and progress of a disease of some sort. Otherwise, I should certainly have included Cecil Woodham-Smith's terrifying book on the Irish potato famine of the 1840s:

Cecil Woodham-Smith. The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845-9. 1962. London: Readers Union Ltd. (Hamish Hamilton), 1962.

The potato blight was a disease, mind you - just not one that affected humans directly. Perhaps another way of saying it, then, would be to link the texts to one of the great pandemics of history:

That's what I've tried to do, then - though of course the result remains very subjective and undoubtedly excludes large numbers of excellent texts which I happen not to have come across or read as yet.

Giovanni Boccaccio. Il Decameron. 1350-53. Ed. Carlo Salinari. 1963. 2 vols. Universale Laterza, 26-27. 1966. Torino: Editori Laterza, 1975.

This seems like an excellent place to start. It's often forgotten that the motivation for the ten days of collective storytelling that constitute Boccaccio's Decameron is the need for various noblemen and women to isolate themselves from the Black Death, at that point rampaging through Florence.

Seen this way, there's a certain cruel frivolity about these stories of love, lust, cuckoldry and other subjects dear to the human heart. Pasolini's 1971 film does a good job of bringing out these ironies, and subverting their apparent 'joyousness' with some sense of the unpleasant realities their tellers are working so hard to conceal.

Albert Camus. La Peste. 1947. Ed. W. J. Strachan. 1959. Methuen’s Twentieth Century Texts. London: Methuen and Co. Ltd., 1965.

This is the great-grandaddy of all 'Plague' narratives. I reread it recently - last year, in fact - before any of the COVID-19 events were even in prospect. It was a little more ponderous than I remembered it, though of course my command of French may have deteriorated since then.

In any case, it remains as telling now as it ever was. I have to confess that I didn't realise, when I first read it as a teenager, how closely it was based on real events. Now I see that as a strength - its allegory of moral degradation and human torpor when faced by genuinely challenging events remains as true as ever. And it's no longer necessary to read it solely as an allegory of the Second World War.

The plague seems as present to us now as the war was for its first readers in 1947.

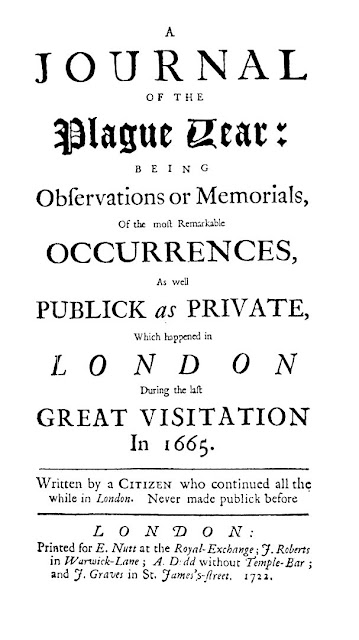

Daniel Defoe. A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations or Memorials of the Most Remarkable Occurrences, as well Public as Private, which Happened in London during the Last Great Visitation in 1665. Written by a Citizen who Continued all the while in London. Never made Public Before. 1722. Ed. Anthony Burgess & Christopher Bristow. Introduction by Anthony Burgess. 1966. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

But then again, perhaps I'm wrong. Maybe this is the quintessential plague narrative against all others must be measured. It was, apparently, Elizabeth Bishop's favourite book, and there's something about the cool precision of her own writing which does remind one of Defoe's marvellously offhand and deadpan account of the horrors of one of London's many plague years - which seems to have been literally burned out of the city by the Great Fire of London.

Things are rarely that simple, though. It came back, as plagues are wont to do, but never with quite the same virulence as during this first major outbreak.

For a long time it was thought to be a genuine eye-witness account, but - while Defoe definitely collected a large number of such stories from his older contemporaries - he was five at the time, so is unlikely to have had many experiences of his own to contribute.

Horton Foote: Three Plays from the Orphans' Home Cycle: Courtship / Valentine's Day / 1918. 1987. New York: Grove Press, 1994.

It's hard to find good accounts of the 1918 influenza epidemic. This rather subdued play chronicling the progress of the epidemic in a small town in the USA started life as a 1985 film, but can now be read in its proper place as part of Horton Foote's immense chronicle of Southern life in the early twentieth century.

Foote, probably best known for his original screenplay Tender Mercies (1983) and the teleplay The Trip to Bountiful (1953), has a tendency to stress the uneventful. It could be argued that this is the best tone to take when writing about this cruellest of epidemics, spreading like wildfire both among returning servicemen and the families that awaited them.

There's a story that Guillaume Apollinaire, lying sick of the 'flu in a Paris hospital in 1918, heard the crowds outside chanting "À bas Guillaume" [Down with William]. They were of course referring to Kaiser Wilhelm, who'd just been forced to abdicate, but the poet took it personally. He died shortly afterwards, so this rather mordant bon mot is one of the last things recorded about him and his extraordinary life.

Stephen King. The Stand: The Complete and Uncut Edition. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1990.

Did Stephen King predict it all? Well, it's true that his 1978 novel The Stand (reissued in a revised and greatly expanded form in 1990) does imagine most of the population of the earth being wiped out by an aberrant strain of the 'flu to which only a very few turn out to be immune.

After that, however, things become distinctly more apocalyptic - which may be disappointing to genuine epidemophiles (if that's a real word ...) It's certainly among his most memorable works, and might arguably be the finest of all.

We're promised a new filmed version soon to replace the rather disappointing 1994 TV miniseries. Whether it can be adequately filmed remains to be seen, especially given the recent debacle of the intensely disappointing Dark Tower movie.

William Rosen. Justinian’s Flea: Plague, Empire and The Birth of Europe. 2006. London: Pimlico, 2008.

This is a truly fascinating book, which attempts to plot the progress of the Byzantine emperor Justinian's Mediterranean campaigns alongside the parallel conquests of the Bubonic plague bacillus.

That might sound a little gimmicky, but the author's decision to try to compare epidemiology with social and military history results in a intriguing mixture of the familiar and the arcane which is guaranteed to inform virtually any reader, no matter how specialised he or she may be.

The accounts of the plague itself are horrific beyond measure, and give considerable backing to the author's contention that it may have been vitally instrumental both in the spread of Islam and the subsequent growth of the nation states of Europe.

Randy Shilts. And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic. 1987. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988.

If you've seen the film, you know the story - how the inertia of governments, societal prejudice against homosexual lifestyles, and jealousy among scientists combined to delay any concerted response against the AIDS virus until it was far too late to prevent its spread.

It's very much worth reading the book, though, even if you think you know what happened. It's too early to say as yet, but there are some indications - as in the article here - that some of the same processes may be playing a part this time round, again.

Robert B. Strassler, ed. The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to The Peloponnesian War. Trans. Richard Crawley. 1874. Introduction by Victor Davis Hanson. 1996. Free Press. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2008.

Thucydides' account, in Book II of his grim history of the follies and hubris of Athens in its twenty-year war with Sparta, of the plague that afflicted his native city in the second year of the conflict, remains an indispensable source on the effects of such outbreaks in the pre-scientific era.

Thucydides employs his customary understatement when chronicling the effects of the illness, which unfortunately means that he failed to provide enough detail for a final identification of the pathogen to be confirmed.

It was generally regarded, until recently, to have been the earliest recorded outbreak of bubonic plague, but more recent suggestions include typhus, smallpox, measles, and toxic shock syndrome.

Barbara W. Tuchman. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980.

JFK's favourite historian, Barbara Tuchman, developed a huge reputation as a sage due to the fact that the former is reliably claimed to have used the latter's Pulitzer-prize winning book about 1914, The Guns of August, as a guide to his conduct during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Some of her later titles - such as The March of Folly (1984), a study of political and military incompetence throughout history - may have suffered from an excess of ideology and editorialising, but A Distant Mirror (1978) still has its fans, myself among them.

Certainly it's an ambitious project - to parallel the tumultuous events of the twentieth century with those of the distant fourteenth - but the result is certainly intriguing. I wouldn't say that it succeeds in convincing me of the validity of the comparison, but it does give a very interesting picture of those times, dominated - in Western Europe at least - by the twin scourges of the Black Death and the Hundred Years War.

With these few provisos, it's a book I would highly recommend. Mind you, the title 'popular' or 'narrative' historian to me seems more of a badge of honour than a pretext for academic sneering - other, more professional readers may be less convinced.

Philip Ziegler. The Black Death. 1969. A Pelican Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

I'm sure that many histories of the Black Death have been published since this one by Philip Ziegler. He displays a touching faith in the medical science of his time, and its decoding of the basic facts of the epidemic. The more recent Benedict Gummer book pictured at the top of this post calls that and many other aspects of his narrative into question.

Despite all that, there's a certain directness and lack of pretension about Ziegler's writing which makes it still well worth reading after 50 years.

Mind you, any real study of the epidemic would have to take into account the large amount of revisionist scholarship which has appeared since then, but you have to start somewhere, and Ziegler seems a very good place to begin.

•

So there you go. Those are the main exhibits in my list, anyway. Feel free, if you wish, to add any suggestions of your own. I'd rather think of this post as a pretext for conversation than as any kind of last word on the subject.