The other day a bunch of us were sitting around talking about books (as you do), when someone asked us each to name our favourite author. The answers were pretty interesting - and quite revealing. Bronwyn said 'Tracey Slaughter,' her sister Thérèse said 'Anne Carson,' Martin said 'Salman Rushdie,' I said 'Guillaume Apollinaire,' and my brother-in-law Greg said 'George Orwell.'

I guess on another day any one of us might have mentioned somebody else ('Stephen King' would probably have been more accurate for me, if the truth be told). But Orwell - that was the name that really struck me, and the response I envied most.

I've been reading his books for forty years, I'm astonished to discover. My second-hand copy of the 'Uniform Edition' of Down and Out in Paris and London cost me 20 cents in 1977, I see on the inside flap, and I acquired copies of The Road to Wigan Pier and Homage to Catalonia not much later. I'm sure I'd already read Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four by then, though it wasn't till I bought the large hardback 'Octopus Books' edition of his complete novels that I read the other ones. Coming Up for Air is probably my favourite book of his, actually.

- Orwell, George. Down and Out in Paris and London. 1933. Uniform Edition. 1949. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd., 1951.

- Orwell, George. The Road to Wigan Pier. 1937. Uniform Edition. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd., 1959.

- Orwell, George. Homage to Catalonia, & Looking Back on the Spanish War. 1938 & 1953. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Orwell, George. Burmese Days / A Clergyman's Daughter / Keep the Aspidistra Flying / Coming Up for Air / Animal Farm / Nineteen Eighty-Four. 1934, 1935, 1936, 1939, 1945, 1949. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Limited / Octopus Books Limited, 1976.

- Orwell, George, & Reginald Reynolds, ed. British Pamphleteers. Volume 1: From the 16th Century to the French Revolution. London: Allan Wingate, 1948.

Nine books: 6 novels, 3 books of non-fiction reportage, plus a couple of collections of reprinted essays: that was his life's work. Or all of it that was accessible to us for a long time, that is.

There was all the fuss about him when the year 1984 finally dawned, of course. I dutifully went out and bought the facsimile edition of the manuscript of the novel. More significantly, though, it must have been around then that I discovered the Penguin editions of his Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters:

- Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four: The Facsimile of the Extant Manuscript. Ed. Peter Davison. Preface by Daniel G. Siegel. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Limited / Weston, Massachusetts: M & S Press Inc., 1984.

- Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 1: An Age Like This, 1920–1940. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 2: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

- Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 3: As I Please, 1943–1945. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 4: In Front of Your Nose, 1945–1950. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

That was an absolute revelation. For the first time it was possible to get some idea of what it must have felt like to be 'George Orwell' - all the ups and downs of his extraordinary life and times, from the slums of the Depression through the Spanish War through the Second World War and out the other side into postwar austerity. I still think this four-volume collection is a miracle of good taste and good editing.

It did, though, have the effect of making me feel that I now knew the man inside out. I did buy the volumes of hitherto undiscovered War Broadcasts which appeared in 1985, but it was with a certain reluctance. They were - to tell the truth - a little tedious taken out of context, and the great thing about Ian Angus and Sonia Orwell's tapestry had been the discovery that Orwell almost never wrote a boring or superfluous word.

- Orwell, George. The War Broadcasts. Ed. W. J. West. 1985. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

- Orwell, George. The War Commentaries. Ed. W. J. West. 1985. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

That's where I stopped. For the past thirty years I've refreshed my memory of his work from the collected edition from time to time, but I haven't read each of the successive Orwell biographies, full as each of them has been of hitherto unsuspected 'facts' (that he was an exhibitionist, that he wasn't an exhibitionist, that he calculated his public persona carefully, that he stumbled into his public persona, etc. etc.) I was aware that there was some monstrous multi-volumed beast called the Complete Works, but I assumed that it mostly repeated what I already knew.

- Buddicom, Jacintha. Eric and Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell. London: Leslie Frewin Publishers Limited, 1974.

- Stansky, Peter, & William Abrahams. The Unknown Orwell. 1972. A Paladin Book. Frogmore, St. Albans, Herts.: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974.

- Stansky, Peter, & William Abrahams. Orwell: The Transformation. 1979. A Paladin Book. Frogmore, St. Albans, Herts.: Granada Publishing Limited, 1981.

- Crick, Bernard. George Orwell: A Life. 1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

- Coppard, Audrey, & Bernard Crick. Orwell Remembered. Ariel Books. London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1984.

- Wadhams, Stephen, ed. Remembering Orwell. Introduction by George Woodcock. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984.

That is, until the other day when I ran across a second-hand copy of Orwell's Diaries, edited by a certain Peter Davison (not the Dr. Who actor, in case you were wondering), which claimed on its blurb to be the closest thing to the 'autobiography he never wrote.'

I bought it, of course, and in the process of investigating its introduction and apparatus, chanced on the extraordinary saga of Davison's own forty-year struggle with Orwell's work. (You can read his fascinating 2012 essay "The Troubled History Behind George Orwell's Complete Works" here).

- Orwell, George. Diaries. Ed. Peter Davison. Harvill Secker. London: Random House, 2009.

- Orwell, George. A Life in Letters. Ed. Peter Davison. 2010. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2011.

The critical response to Peter Davison's self-imposed task has been, to be honest, a little mixed. Quite a few reviewers have criticised him for his 'boots and all' approach to Orwell's work, preferring the more nuanced approach of Ian Angus and Orwell's second wife Sonia. But when I read in one of these pieces that the latter had attempted pretty systematically to expunge his first wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy (who died in 1945) from the record, I began to think that there might be something to be said for the wholesale approach after all.

And so it has proved. I'm steadily working my way through the eleven volumes of what Davidson describes as "his and his wife Eileen’s letters (some 1,100), 265 articles, 380 reviews, lecture notes and research materials, diaries (apart from one or two still believed to be held in the NKVD Archive in Moscow), his hundreds of BBC broadcasts to India and the arrangements for making those, together with a selection of letters written to him." True, some of the juvenilia is a bit lame, but pretty much from the publication of his first pieces of journalism in Paris, the authentic voice is very much in evidence.

Does anyone deserve to be documented on quite this scale? Well, I'm sure that it would horrify Orwell himself, but if anyone merits it, he does. Even his most hurried reviews are always sensible and interesting - and have the effect of providing a potted history of two decades of English intellectual life, as well as their many other virtues. The letters and diaries are also fascinating. Reading it is really like discovering a whole new Orwell: not the careful craftsman of the nine books, or the more expansive - but still rigorously controlled - journalist of the Ian Angus / Sonia Orwell selection, but a warts-and-all portrait of the artiste engagé.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 10: A Kind of Compulsion: 1903–1936. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2000.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 11: Facing Unpleasant Facts: 1937–1939. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2000.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 12: A Patriot After All: 1940–1941. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2002.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 13: All Propaganda Is Lies: 1941–1942. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 14: Keeping Our Little Corner Clean: 1942–1943. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 15: Two Wasted Years: 1943. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 16: I Have Tried to Tell the Truth: 1943–1944. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 17: I Belong to the Left: 1945. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 18: Smothered Under Journalism: 1946. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 19: It Is What I Think: 1947–1948. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2002.

- Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 20: Our Job Is to Make Life Worth Living: 1949–1950. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2002.

- Davison, Peter, ed. The Lost Orwell: Being a Supplement to The Complete Works of George Orwell. London: Timewell Press Limited, 2006.

I'm astonished that I didn't think to investigate these 11 volumes (plus supplementary volume) before. In a sense, though, I'm glad. Now I can savour the treat fully, and at my leisure: rather than waiting for each new volume to appear in a fever of impatience.

There is, of course - given Davison's mania for completeness - more to it than that. The first nine volumes of his edition provide critical texts for each of the novels and books of reportage (texts more readily available now through Penguin Modern Classics). He has also edited four volumes of selections from the edition, each focussed on a particular book of Orwell's:

- Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell and the Dispossessed: Down and Out in Paris and London in the Context of Essays, Reviews and Letters Selected from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Peter Clarke. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell's England: The Road to Wigan Pier in the Context of Essays, Reviews and Letters Selected from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Ben Pimlott. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell in Spain: The Full Text of Homage to Catalonia with Associated Articles, Reviews and Letters from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Christopher Hitchens. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.

- Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell and Politics: Animal Farm in the Context of Essays, Reviews and Letters Selected from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Timothy Garton Ash. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.

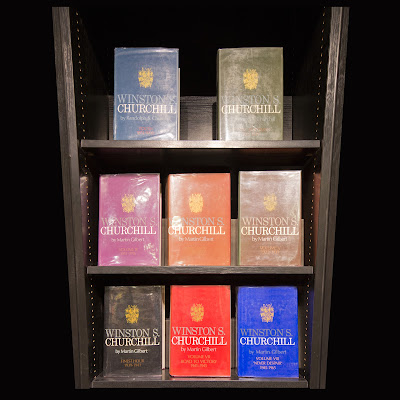

Simon Schama's classic TV series on the History of Britain concludes with an episode entitled "The Two Winstons," contrasting Orwell's Winston Smith (from 1984) with that other Winston, Winston Churchill, as a way of exploring the UK in the twentieth century.

It works quite well, really. While I demonstrated in my previous post that I have spent quite a lot of time poring over Winston Churchill's literary remains, there is, I'm afraid, no comparison with the interest I feel in Orwell's. He really is one of the greatest writers of the last century, and it's nice to be able to see his work whole and entire at last, thanks to the largely thankless labours of that culture-hero Peter Davison.

George Orwell: Reportage: Down and Out in Paris and London, Funny but Not Vulgar, The Road to Wigan Pier, My Country Right or Left & Homage to Catalonia (Folio Society, 1998)