It’s an optical amusement, a punctured surface letting light pour through holes cut out of the picture. Moon, army tents and the windows of houses and St Mary’s church glow or flicker with luminance. Between them move women and children as well as soldiers. Steamers, a brig and a schooner ride on the moonlit sea. Part and not part of the scene is the artist’s son, who lies three days buried in the churchyard at the foot of the hill where his father sits sketching the arrival of imperial troops. Now walk away from the painting when it is lit up and see how light falls into the world on this side of the picture surface. Is this what the artist meant by his cut outs? Is this the meaning of every magic lantern slide?.

In all the excitement of Labour weekend, don’t miss the launch of Michele Leggot’s luminous new poetry collection on Tuesday evening!

7–8.30pm, Tuesday 24 October 2017

Devonport Library, 2 Victoria Road, Devonport, Auckland

Koha appreciated.

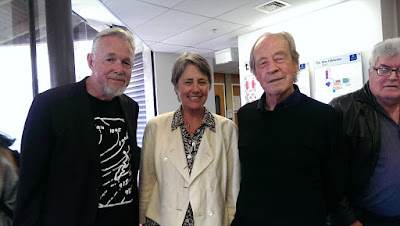

We had an excellent time on Tuesday night. The Devonport Library Associates once again gave us a rousing welcome: Jan Mason and Paul Beechman gave the opening speeches, and Ian Free presented Michele and myself with some lovely bottles of bubbly. Sam Ellworthy was there to represent Auckland University Press, her publisher, and closed off the evening with a few words.

Tim Page did his usual brilliant job as sound-master, as well as creating a wonderful animation of the book's cover image, Edwin Harris's 1860 painting 'New Plymouth under Siege.' The original has little holes in it which look like twinkling lights when illuminated from the other side. Tim got us as close to that as one can imagine with his screen projection of this strange, haunting, rather Gothic work:

Edwin Harris: ‘New Plymouth under Siege – 40th Regiment, Marsland Hill, Taranaki 1860’ (3 August 1860)

My job was twofold: first to introduce Michele and her book, and secondly to interview her about it. it's always a bit difficult to make these setpiece 'conversations' sound at all spontaneous, but various people told me afterwards that they thought we'd carried it off.

Michele really didn't know what I was going to ask in advance (I hardly did myself), but she certainly had a lot to say in response. My idea was to try and anticipate what questions people might have on looking into the book, and to try to cover as many as possible of those in advance. Here we are in full cry:

Of course there was also a reading. Michele read four sections from the closing sequence, 'Figures in the Distance,' immediately after my launch speech. Here she is reading, with the help of her ipod:

I was in two minds whether or not to include the text of my speech. It's hard to recover the spontaneity of a live event, but as long as you bear in mind that it is written to be spoken, not read, I don't suppose there's any harm in it:

Well, needless to say, I felt very flattered when Michele Leggott asked me to launch her latest book of poems, Vanishing Points. Flattered and somewhat terrified. It’s true that I’ve been reading and collecting her work for well over 20 years, and I’ve been teaching it at Massey University for almost a decade now, but I still felt quite a weight of responsibility pressing down on my shoulders!

One thing that Michele’s poetry is not, is simple. It’s hard to take anything in it precisely at face value: what seems like (and is) a beautiful lyrical phrase may be a borrowing from an unsung local poet – a tangle of Latin names can be a reference to an obsolete star-chart with pinpricks for the various constellations.

The first time I reviewed one of her books, as far as I can see, in 1999, I ended by saying “the reading has only begun.” At the time, I suspect I was just looking for a good line to finish on, but there was a truth there I didn’t yet suspect. Certainly, I’ve been reading in that book, and all her others, ever since.

But how should we read this particular book? “Read! Just keep reading. Understanding comes of itself,” was the answer German poet Paul Celan gave to critics who called his work obscure or difficult. With that in mind, I’ve chosen two touchstones from the volume I’m sure you’re all holding in your hands, or (if not) are planning to purchase presently.

The first is a phrase from the American poet Emily Dickinson, referred to in the notes at the back of the book: “If ever you need to say something … tell it slant.” [123] The second is a quote from the great, blind Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges: “I made a decision. I said to myself: since I have lost the beloved world of appearances, I must create something else.” [35]

With these two phrases in mind, I’d like you to look at the cover of Michele’s book. It’s a painting of the just-landed Imperial troops, camped near New Plymouth in August 1860. The wonderful thing about it is the way the light of the campfires shines through the painting: little holes cut in the canvas designed to give the illusion of life and movement.

“War feels to me an oblique place,” wrote the reclusive New England poet Emily Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in February 1863, at one of the darkest points of the American Civil War. Higginson, a militant Abolitionist, was the Colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first officially authorized black regiment in American history. He was, in short, a very important and admirable man in his own right. Perhaps it’s unfair of posterity to have largely forgotten him except as the recipient of these letters from one of America’s greatest poets.

New Zealand’s Land Wars of the 1860s may have been on a much smaller scale, but they were just as terrifying and devastating for the people of Taranaki – both Māori and Pakeha – in the early 1860s. In her sequence “The Fascicles,” Michele transforms a real distant relative into a poet in the Dickinson tradition. Just as Emily Dickinson left nearly 1800 poems behind her when she died in 1886, many collected in tidy sewn-up booklets or fascicles, so Dorcas (or Dorrie) Carrell “in Lyttelton, daughter of a soldier, wife of a gardener” [75] provides a pretext for “imagining a nineteenth-century woman writing on the outskirts of empire as bitter racial conflict erupts around her.” [123]

There’s an amazing corollary to this attempt to “Tell all the truth but tell it slant” (in Dickinson’s words). Having repurposed one of her family as a war poet, Michele was fortunate enough to discover the traces of a real poet, Emily Harris, the daughter of the Edwin Harris who painted the picture of Taranaki at war on the wall over there, whose collected works so far consist of copious letters and diaries, but also two very interesting poems. “Emily and her Sisters,” the seventh of the sequences collected here, tells certain aspects of that story.

It’s nothing but the strictest truth to say, then (as Michele does at the back of the book), that one should:

walk away from the painting when it is lit up and see how light falls into the world on this side of the picture surface. Is this what the artist meant by his cut-outs? Is this the meaning of every magic lantern slide? [124]I despair of doing justice to the richness of this new collection of Michele’s – to my mind, her most daring and ambitious work since the NZ Book Award-winning DIA in 1994. There are eight sequences here, with a strong collective focus on the life and love-giving activities which go on alongside what Shakespeare calls in Othello “the big wars”: children, family, eating, painting, swimming. One of my favourites among them is the final sequence, “Figures in the Distance,” which offers a series of insights into the world of Michele’s guide-dog Olive – take a bow, Olive – amongst other family members, many of whom, I’m glad to see, have been able to come along here tonight.

This is a radiant, complex, yet very approachable book. It is, in its own way, I’m quite convinced, a masterpiece. We have a great poet among us. You’d be quite crazy to leave here tonight without a copy of Vanishing Points.

At this point, then, I’d like to hand over to Michele, who will read some pieces from the sequence “Figures in the Distance." After that the two of us will have a short conversation about the book, and I’ll try and ask, on your behalf, some of the questions I think you’d like to have answered about how it all connects and how the various parts of it came about.

.jpg)