Recently we decided to get some new bookcases. Above you can see the before: how they looked on delivery day. Below you can see after: how they look now I've finished arranging them:

It's clear that you'll need a bit of context before you can understand how (and why) I got from point A to point B, however. First of all, the room itself:

This was once my sister Anne's bedroom. After that, it was used as an office. But it's always been a slightly awkward space: too cramped for a guest room, and too hot and stuffy to work in comfortably in the afternoons. Accordingly, we took out all the furniture:

The first set of books I transplanted there were my American history books. As you'll know if you read this blog at all, I have a fascination with all aspects of the American civil war, but actually I'm partial to most of the great American narrative historians: Washington Irving, William H. Prescott, Francis Parkman, and their twentieth century counterparts: Robert Caro, Shelby Foote, David McCullough, Barbara Tuchman, and Edmund Wilson:

This was followed by children's books and Russian books, in each of the remaining bookcases:

Bronwyn gave me two beautiful bookends for Christmas, a Chinese boy and girl each reading a book. The question was what to put between them?

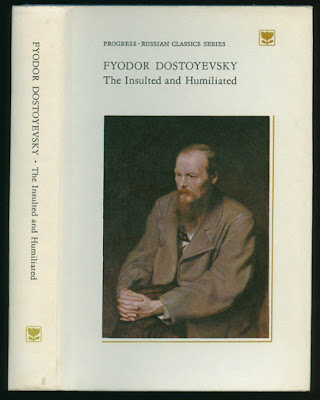

My sister had a particular fondness for books published by the Russian Foreign Languages Publishing House, with their distinctive cover designs and charmingly eccentric typefaces:

I therefore decided to put all the volumes I had in this series (including some that used to belong to her), and put them on top of a central pair of bookcases, counterpointing the three placed against the wall:

The Moscow-based Foreign Languages Publishing House, founded in 1946, included a series of Classics of Russian Literature, alongside Soviet Literature, Marxist-Leninist Classics, and various others (including the endearingly titled "Soviet Children's Library for Tiny Tots").

The translations were often clumsy and stilted by comparison with the practised smoothness of (say) Constance Garnett's versions, but that just seemed to add to their charms. They seemed so intensely Russian, somehow. Here's a list of the ones I've managed to assemble so far:

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. Poor Folk. 1846. Trans. Lev Navrozov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Dostoyevsky, F. White Nights / A Faint Heart / A Christmas Party and a Wedding / The Little Hero. 1848, 1848, 1848 & 1857. Trans. O. N. Shartse. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Insulted and Humiliated. 1861. Ed. Olga Shartse. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d. [1957].

- Dostoyevsky, F. Notes from a Dead House. 1862. Trans. L. Navrozov & Y. Guralsky. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. My Uncle’s Dream / Most Unfortunate / The Gambler. 1859, 1862 & 1867. Trans. Ivy Litvinova. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Dostoyevsky, F. A Funny Man’s Dream: Our Man Marei / The Meek One: A Fantasy / A Funny Man’s Dream: A Fantasy / Stepanchikovo and Its Inhabitants. 1876, 1876, 1877 & 1859. Trans. Olga Shartse. Ed. Julius Katzer. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Gogol, Nikolai. Evenings Near the Village of Dikanka: Stories Published by Bee-Keeper Rudi Panko. 1831-1832. Ed. Ovid Gorchakov. Illustrated by A. Kanevsky. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Gogol, Nikolai. Mirgorod: Being a Continuation of Evenings in a Village Near Dikanka. 1835. Illustrated by A. Kanevsky. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Kuprin, Alexander. The Garnet Bracelet and Other Stories. Trans. Stepan Apresyan. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Lermontov, Mikhail.A Hero of Our Time. Trans. Martin Parker. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1956.

- Pushkin, A. The Tales of Ivan Belkin. 1830. Trans. Ivy & Tatiana Litvinov. Illustrated by D. A. Shmarinov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954.

- Pushkin, A. S. Dubrovsky. 1833. Trans. Ivy & Tatiana Litvinov. Illustrated by V. Kolganov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1955.

- Saltykov-Shchedrin, Mikhail. Judas Golovlyov. 1880. Trans. Olga Shartse. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Tolstoy, Lev. Childhood, Boyhood, Youth. 1852, 1854 & 1857. Ed. D. Bitsi. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Tolstoy, Lev. Resurrection: A Novel. 1899. Trans. Louise Maude. Ed. L. Kolesnikov. Illustrated by O. Pasternak. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Tolstoy, Lev. Short Stories. Trans. Margaret Wettlin. Illustrated by V. Basov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Wettlin, Margaret, trans. Reminiscences of Lev Tolstoi by His Contemporaries. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Turgenev, Ivan. A Hunter’s Sketches. 1852. Ed. O. Gorchakov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Turgenev, Ivan. Three Short Novels: Asya / First Love / Spring Torrents. 1857, 1860 & 1871. Trans. Ivy & Tatiana Litvinov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

•

And here's an alphabetically arranged list (by author and title) of some of the other volumes I don't yet own::

- Ivan Bunin

- Shadowed Paths. Translated from the Russian by Olga Shartse, n.d.

- Anton Chekhov

- Three Years. c. 1950. 140 pp.

- V. M. Garshin

- The Scarlet Flower. 1959. 179 pp. Frontis of author. Illustrated with black & white drawings. Navy blue cloth cover ... with red & gold lettering on its spine and a red flower on its front board.

- Nikolai Vasilevich Gogol

- Taras Bulba. Translated from the Russian by O.A. Gorchakov. Designed by D. Bisti (illustrator). c. 1958. 143 pp.

- Nikolai Leskov

- The Enchanted Wanderer and Other Stories. Translated By George H. Hanna. Frontispiece photo of the author. n.d. 346 pp.

- Alexander Pushkin [Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin]

- The Captain's Daughter. 1954. Beige paper over boards, gilt spine and cover titles.

- M. Saltykov-Schedrin

- Tales from M. Saltykov-Shchedrin. Collection of short stories. Translated by Dorian Rottenberg and edited by John Gibbons. n.d.

- Lev Tolstoi [Leo Tolstoy]

- The Cossacks: A Story of the Caucasus. Edited by R. Daglish. c. 1965.

- Tales of Sevastopol. Illustrated by Pyotr Pavlinov. Classics of Russian Literature No. 17. 1950. 154 printed pages of text with one tipped-in colour plate and full-page monochrome illustrations throughout. Hard back binding in publisher's original decorated duck egg blue cloth covers. Gilt title and author lettering to the spine and to the upper panel. Quarto size: 10 1/2'' x 8 1/4''.

- I. S. Turgenev [Turgenev, Ivan] [Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev]

- Fathers and Sons. Translated from the Russian by Bernard Isaacs. Illustrated by Konstantin Rudakov. 1951. 214 pp. 9 tipped in plates.

- MUMU. n.d. 78pp. "Never in the whole of literature has there been a more shattering protest against cruel tyranny."

- On the Eve. 1958. Small purple hardcover with black lettering and design on cover, 179 pp.

- Rudin. Translated by O. Gorchakov. Illustrated by V. Sveshnikov. Designed by E. Fomina. 1954. 138 pp.

•

As well as all of these Russian classics, there was the possibly even more characteristic and spirited companion library of Soviet literature:

- Gorky, Maxim. Childhood. 1913. Trans. Margaret Wettlin. Library of Selected Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Gorky, Maxim. My Universities. 1923. Trans. Helen Altschuler. Library of Selected Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Gorky, Maxim. Foma Gordeyev. 1901. Trans. Margaret Wettlin. Library of Selected Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Gorky, Maxim. The Artamonovs. 1927. Trans. Helen Altschuler. Illustrated by D. Shmarinov. Library of Selected Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Rybakov, Anatoly. The Dirk: A Story. Trans. David Skvirsky. Illustrated by O. Vereisky. Soviet Literature for Young People. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954.

- Sholokhov, Mikhail. And Quiet Flows the Don. 1926-40. 4 vols. Trans. Stephen Garry. 1934. Revised and Completed by Robert Daglish. Library of Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Sholokhov, Mikhail. Virgin Soil Upturned. 1932. Trans. R. Daglish. 1935. Library of Selected Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Solovyov, Leonid. The Enchanted Prince: Book Two of the Adventures of Khoja Nasreddin. 1954. Trans. Bernard Isaacs. Library of Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1957.

- Tolstoy, Alexei. The Lame Prince: A Story. 1912. Trans. Leonid Lamm. Library of Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Tolstoy, Alexei. Nikita’s Childhood. 1920. Ed. K. Y. Vladimirsky & V. A. Zaitsev. Trans. V. Korotky. Russian Readers for Beginners. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

- Tolstoy, Alexei. Aelita. 1923. Trans. Lucy Flaxman. Ed. V. Shneerson. Library of Soviet Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

•

There was a shake-up in 1964, at the end of the Khrushchev era. The original Foreign Languages Publishing House, with its zany, eccentric designs, was split into two separate publishers: Progress and Mir. The former specialised in literature, often reprinting the same texts as its predecessor in a rather more sober and official-looking manner, while the latter handled scientific and technical books.

Here's a list of the "Progress Publishers" books I have:

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Insulted and Humiliated. 1861. Trans. Olga Shartse. 1957. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976.

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Idiot. 1868. Trans. Julius Katzer. 1971. Russian Classics Series. 2 vols. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975.

- Gogol, Nikolai. A Selection, I: from Mirgorod / from St. Petersburg Stories / The Government Inspector. Trans. Christopher English. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1980.

- Gogol, Nikolai. A Selection, II: Village Evenings near Dikanka / from Mirgorod. Preface by S. Mashinsky. Trans. Christopher English & Angus Rosburgh. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1981.

- Goncharov, Ivan. The Same Old Story: A Novel. 1847. Trans. Ivy Litvinova. Illustrated by Orest Vereisky. 1957. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975.

- Gorky, Maxim. Letters. Trans. V. Dutt. Ed. P. Cockerell. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1966.

- Lermontov, Mikhail. Selected Works. Trans. Martin Parker, Avril Pyman, Irina Zheleznova, et al. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976.

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Poems. Trans. Dorian Rottenberg. Illustrated by Vladimir Ilyushchenko. 1972. Soviet Authors Library. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976.

- Pushkin, Alexander. Selected Works in Two Volumes. Volume One: Poetry. Introduction by A. Tvardovsky. 1974. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1976.

- Pushkin, Alexander. Selected Works in Two Volumes. Volume Two: Prose Works. Russian Classics Series. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974.

I hope that this new bookroom constitutes a fitting memorial for my wonderful (and sorely missed) sister Anne. It contains many of the children's books and Russian novels she loved, and is meant to remind us of her - as well as existing for purposes of pure entertainment, of course. She wouldn't have wanted it any other way.