Clearly I'm not the first one to notice the extraordinary prescience shown by E. M. Forster in his long short story "The Machine Stops," first published in The Oxford and Cambridge Review in November 1909.

Forster envisages a world where people live cocooned in little cells, with audiovisual contact with one another, and minimal travel from place to place. His protagonist, Vashti, is largely content with her situation, and displays nothing but irritation at the attempts of her son, Kuno, to interest her in the forbidden regions outside.

Everything - nourishment, entertainment, contact - is supplied by the Machine, which is now the main deity worshipped by mankind, despite having been originally designed to serve them. Now, however, the machine has started to falter, to lag in its daily attentions to the human parasites that infest it.

Kuno wants his mother to accompany him outside, where he is sure that he once saw some living human beings. Her reluctance to do so spells her own doom. As the two of them die, however, they at least have the satisfaction of seeing the possibility of escape from the Machine's mechanical womb.

"But, Kuno, is it true? Are there still men on the surface of the earth? Is this - this tunnel, this poisoned darkness - really not the end?"

He replied: "I have seen them, spoken to them, loved them. They are hiding in the mist and the ferns until our civilisation stops. Today they are the Homeless - tomorrow -"

"Oh, tomorrow - some fool will start the Machine again, tomorrow."

"Never," said Kuno, "never. Humanity has learnt its lesson."

As he spoke, the whole city was broken like a honeycomb. An airship had sailed in through the vomitory into a ruined wharf. It crashed downwards, exploding as it went, rending gallery after galley with its wings of steel. For a moment they saw the nations of the dead, and, before they joined them, scraps of the untainted sky.

Forster himself called his story "a reaction to one of the earlier heavens of H. G. Wells" - presumably the one depicted in the latter's novel When the Sleeper Wakes (1899) - reissued, in revised form, as The Sleeper Awakes in 1912.

Not that Wells's picture of the future - in this novel, at least - is a narrowly utopian one. The society his sleeper, Graham, wakes into is a profoundly troubled one. The amount of his own savings have accumulated, due to compound interest, during the long centuries of his sleep, to such an incredible total that they are now the principal economic mainstay of the world. The rest of the book examines the implications of such capitalist plutocracy as against the apparent hope provided by revolutionary socialism.

Both are found wanting in this bleak early vision by a writer later criticised for his naive acceptance of purely scientific values. Once again, if you read his books yourself rather than accepting such bland critical summaries, the actual implications of his work are far more nuanced and complex.

Be that as it may, Wells' truths were certainly different from Forster's. In a sense they embody two contradictory world-views - based, respectively, on the private and the public life. Forster concerned himself almost exclusively with the personal values bound up in his famous adage: "Only connect." His books are all about moments of emotional epiphany and contact over seemingly unbridgeable gulfs of background and class.

W. H. Auden perhaps expressed it best in the last of his 1938 group of Sonnets from China:

XXI

(to E.M. Foster)

Though Italy and King's are far away,

And Truth a subject only bombs discuss,

Our ears unfriendly, still you speak to us,

Insisting that the inner life can pay.

As we dash down the slope of hate with gladness,

You trip us up like an unnoticed stone,

And, just when we are closeted with madness,

You interrupt us like the telephone.

Yes, we are Lucy, Turton, Philip: we

Wish international evil, are delighted

To join the jolly ranks of the benighted

Where reason is denied and love ignored,

But, as we swear our lie, Miss Avery

Comes out into the garden with a sword.

Wells, by contrast, ended in a state of utter despair, as the Second World War erupted to dash into pieces all his hopes of international betterment. The title of his last book Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945) says it all.

Having said that, though, much though I enjoy Forster's fiction and essays, if it came to a choice between the two, I would go for Wells every time. Forster's Collected Short Stories (1950) is 246 pages long. Wells's Short Stories (1927) runs to over 1,000 pages, and includes such masterpieces as "The Time Machine," "A Story of the Days to Come," "A Dream of Armageddon," and dozens of others - it's one of the great books of the twentieth century.

Luckily, I don't have to choose. I can enjoy both of their different insights, and shelve them side-by-side in a propinquity I fear they could never have achieved in their lifetimes.

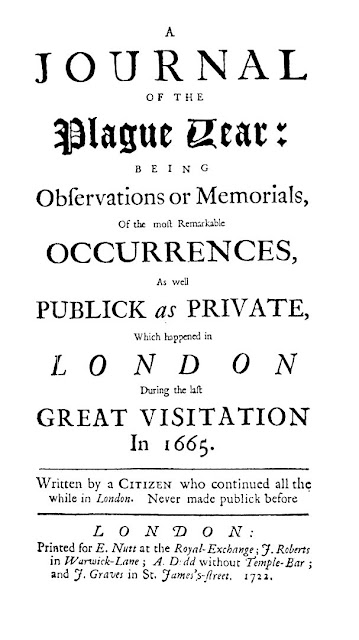

Twelve Modern Short Novels: A Collection of the Shorter Works of Writers of Distinction from the Eighties of the Last Century to the Present Day. Decorations by B. Biro. London: Odhams Press Limited, n.d. (c. 1950s).

I see from the inside of my copy (which is light blue rather than red in colour, but is otherwise identical with that pictured above) that I purchased it on 30th September 1977. It was certainly an auspicious day for me.

You can see from the list of contents below just what a treasure-house of stories this book contains. I'd read very few of these authors previously, and it had the effect of introducing me to some of the real triumphs of late nineteenth / early twentieth-century prose.

- [1887] - Oscar Wilde: "Lord Arthur Savile's Crime: A Study of Duty"

- [1888] - Rudyard Kipling: "The Man Who Would Be King"

- [1902] - Joseph Conrad: "Heart of Darkness"

- [1911] - E. M. Forster: "The Machine Stops"

- [1919] - Max Beerbohm: "Enoch Soames"

- [1922] - Aldous Huxley: "The Gioconda Smile"

- [1927] - Thornton Wilder: "The Bridge of San Luis Rey"

- [1936] - Katherine Anne Porter: "Noon Wine"

- [1936] - Graham Greene: "The Basement Room"

- [1939] - Ernest Hemingway: "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber"

- [1945] - Mary Lavin: "The Becker Wives"

- [1946] - H. E. Bates: "The Cruise of 'The Breadwinner'"

No editor's name for the volume is given - only that of the illustrator, a certain 'B. Biro' (later to be known as Val Biro). He may - for all I know - have chosen the contents as well, but the contingency seems an unlikely one, given his youth at the time, and the sheer size of his graphic output: "3,000 covers in less than 40 years," as Nick Jones revealed in his "Interview with Val Biro, Artist, Illustrator, Author and Book Cover Designer" in Existential Ennui (4/8/14).

Whoever it was who selected these particular stories certainly did me a great favour, though. I suppose that I would have read the more canonical ones sooner or later, but authors such as Katharine Anne Porter and Thornton Wilder were much less familiar currency at the time.

Also, would I really have appreciated "The Machine Stops" quite so much if it hadn't been bookended between the dark profundities of "Heart of Darkness" and the bittersweet satire of Beerbohm's "Enoch Soames"?

"The Basement Room," too. It would be many years before I saw Carol Reed's film The Fallen Idol (1948), and then, I'm afraid, my main impulse was to exclaim that he'd got it wrong. The squalid suburban horrors of Greene's parable had somehow been transferred to the glamorous setting of an embassy.

The lessons screenwriter and director learnt from this experience must have supplied at least some of the ingredients which went into their next collaboration, the immortal Third Man (1949).