How dreary – to be – Somebody!

How public – like a Frog –

To tell one’s name – the livelong June –

To an admiring Bog!

- Emily Dickinson: "I'm Nobody! Who are you?"

Who is [Emily]? What is she, / That all our swains commend her?

Recently I was asked to review a new collection by a veteran local poet for Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook. In my piece I made a passing reference to the line:

'Hope' is the thing with feathersI was a bit surprised to be asked to attribute the quote.

To me it seemed about on a par with being asked to identify the author of "To be or not to be", or "This was their finest hour". These are phrases which have entered the language, and we all know where they come from.

Or do we? Maybe I'm wrong. It's not that I doubt that there are plenty of people out there who haven't heard of Emily Dickinson - but how many of them read reviews in poetry journals? It would be a bit like postulating a physics student who'd never heard of Einstein.

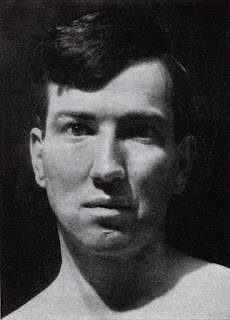

The image above is the only authenticated photograph of the poet, taken when she'd just turned 16. Versions of it have been colourised, redrawn, artificially aged, and generally monkeyed around with over the past century or so since the posthumous discovery of her work in 1890.

The first selection from the almost 1800 poems she left behind in manuscript, edited by the Dickinsons' neighbour Mabel Loomis Todd and well-known man of letters Thomas Wentworth Higginson, was such a success that it was quickly followed by two sequels, published in 1891 and 1896, together with a 2-volume collection of the poet's letters (1894).

After the death of her brother Austin Dickinson (1829-1895), however, the smouldering feud between his wife Susan (1830-1913), and his lover Mabel Loomis Todd (1856-1932) came to a head. The family took back the manuscripts Emily's sister Lavinia had loaned to Todd, and no more new work appeared for another twenty years.

Far from subsiding, the feud reached new levels of intensity after 1914, via a series of competing editions of poems and letters issued by Martha Dickinson Bianchi, Austin and Susan's daughter (and thus Emily's niece), and Millicent Todd Bingham, Mabel Loomis Todd's daughter, which appeared piecemeal over the next thirty years.

A vivid - if somewhat one-sided - account of all this palaver is given in Bingham's book Ancestor’s Brocades: The Literary Début of Emily Dickinson (1945). A more honest and accurate version is included in Lyndall Gordon's recent biography Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family's Feuds (2010).

But that's not really what interests me here. I'm less keen to talk about Dickinson herself than about "Dickinson", the 30-part TV sitcom /dramedy Bronwyn and I have just been watching on Apple TV.

I was a bit doubtful about the concept at first, but the show's weird mixture of contemporary language and attitudes with "period" clothes and mores does seem to work somehow. And one has to admit that there's a certain brutal accuracy to their skewering of such luminaries as Louisa May Alcott, Henry Thoreau, Walt Whitman, et al.

Also, the fact that the show strays further and further into the most abject melodrama the longer it goes on provides a perfect disguise for the fact that most of it is true. It's hard to exaggerate just how weird the Dickinsons' lifestyle really was (by all accounts, at any rate): the two separate-but-conjoined houses, the long periods when none of them were speaking to each other, the drunkenness and adultery.

Nor, it appears, was Emily herself, the Belle of Amherst, quite the shrinking violet of legend. In her 2010 Guardian article "A Bomb in Her Bosom", her biographer Lyndall Gordon calls her "a woman who was fun: a lover who joked; a mystic who mocked heaven."

In Gordon's case, though, she has a ready-made villain to hand for all these misunderstandings: Dickinson's previous "definitive" biographer Richard B. Sewall, who was so much under the thumb of Mabel Loomis Todd that he:

passed on the trove of Todd untruths: that Emily Dickinson had favoured Mabel; that the poet's withdrawal into seclusion had been the result of a family split preceding Mabel's appearance ... The biographer even outdoes the Todds when he suggests that Dickinson's "failure" to publish was a result of a family quarrel.While one should certainly take any biographer's account of the deficiencies of their predecessors with a grain of salt, there may be something to Gordon's contention that Emily and her family were far more dysfunctional than popular legend would allow:

Helpful Mr Higginson, a supporter of women, who thought he was corresponding with an apologetic, self-effacing spinster, was puzzled to find himself "drained" of "nerve-power" after his first visit to [Emily] in 1870. He was unable to describe the creature he found beyond a few surface facts: she had smooth bands of red hair and no good features; she had been deferential and exquisitely clean in her white piqué dress and blue crocheted shawl; and after an initial hesitation, she had proved surprisingly articulate. She had said a lot of strange things, from which Higginson deduced an "abnormal" life.But was she a lesbian? Dickinson's Dickinson certainly is, and the object of her affections is, unequivocally, her brother's wife Sue.

That's not the universal verdict, though:

In a novel of 2006 a spiteful Sue ends up "hating" Emily. In a novel of 2007 Sue becomes a death-dealing Lucrezia Borgia. She awaits her victims in the hall of her house, a vamp in décolleté black velvet waving her fan. Can evil go further? It can. Sue "could make mincemeat pie of the Dickinson sisters and eat it for Christmas dinner".I wish that Lyndall Gordon had thought to supply us with the titles of these two novels. My own quest has (so far) turned up only the following fictional outings:

What if the old maid of Amherst wasn’t an old maid at all? Her older brother, Austin, spoke of Emily as his “wild sister.” ... The poet dons a hundred veils, alternately playing wounded lover, penitent, and female devil. We meet the significant characters of her life, including her tempestuous sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert; her brooding father, Edward; and the Reverend Charles Wadsworth, who may have inspired some of her greatest letters and poems.That somewhat risqué cover illustration seems particularly appropriate for this "astonishing novel that removes Emily Dickinson’s own mysterious mask and reveals the passions and heartbreak of America’s greatest poet."

On a whim the two distinguished authors [Hawthorne and Melville] invite the Dickinson siblings to accompany them on a trip to Boston and New York. In Manhattan they meet journalist Walt Whitman and William Johnson, a runaway slave, and it is there, despite their efforts to control it, that Emily and Herman fall in love.Herman Melville seems to be just about the only distinguished mid-century American writer not included in Dickinson, so it's nice that Healey had already supplied the omission.

The Dickinson household is saved from domestic chaos with the arrival of Ada Concannon, a ‘neat little Irish person, fresh off the boat’. In Amherst in the 1800’s the homesick young maid finds in the gifted middle child, Emily, a fellow feeling. Born on the same day they share a sense of mischief and a love of baking, but Emily’s passion for words is her true vocation. When Ada’s reputation is violated Emily finds herself defending her maid against her own family and those she loves.The Emily in Dickinson seems a bit baking-challenged, so it's nice to know that this one has at least a few domestic talents. Nuala O'Connor is a skilful and inspiring writer whom Bronwyn and I met at a short story conference in Shanghai, so I won't be saying anything critical of this particular addition to the canon of Emily-Dickinson-fiction (or EDF for short).

•

You do begin to wonder at this stage, though, just what aspects of the famed recluse remain to be exploited. I mean, what's next, Emily Dickinson, super-sleuth?

Since you mention it:

A new historical series starring Willa Noble, maid to iconic American poet Emily Dickinson, who solves mysteries with her new employer.In her online interview with Amanda Flower, the author of the 'Emily Dickinson Mystery Series,' Elise Cooper jumps straight in with the question on everyone's lips:

How did you get the idea to use Emily Dickinson?No, she never did. And her poems are indeed "imagery and vague with multiple meanings."

Amanda Flower: Each book’s title will be the first line from one of her famous poems ... I pay tribute to the poems, but do not follow it verbatim [sic.] Her poems are imagery and vague with multiple meanings. She never wrote clearly.

Flower goes on to explain that Emily makes the perfect candidate for a detective because "Her poems are mysterious."

The real characters beside Emily were the maid Margaret O’ Brian. I added a maid assistant, Willa, to tell the story in the same manner that Sherlock Holmes had Watson. I also chose that period of her life, in 1855, where Emily and her sister came to Washington because her father was a member of the House of Representatives. This time was about six years before she went into hiding for the rest of her life as a recluse ...And Emily herself?

She likes to investigate, a good judge of character, ignores societal class, and is loyal. She is also bold, caring, curious, confident, and blunt. She was probably her father’s favorite because he gave her special treatment. She enjoyed wandering around and instead of ... telling her to stop [he] bought her a dog for protection. The dog is real and so his name Carlo, a character in Jane Eyre. He lived for seventeen years, which is unusual for a pure bred Newfoundland. One of the theories is that Emily became a recluse after he passed away.Joking apart, Flowers' series does sound like a lot of fun. And there's something rather pleasing in her conclusion that "The family gave her room to be different, a genius aspect."

When the author sets out on the trail of a forged Emily Dickinson poem that has mysteriously turned up for sale at Sotheby’s in New York, he finds himself drawn into a world of deception and murder. The trail eventually leads, via the casinos of Las Vegas, to Utah and the darkly compelling world of Mark Hofmann, ex-Mormon and one of the most daring literary forgers and remorseless murderers of all time. As the author uncovers Hofmann’s brilliant, and disturbing, career, he takes the reader into the secret world of the Mormon Church and its controversial founder, Joseph Smith.At times one does feel just the slightest tendency towards exploitation in certain authors' attempts to shoehorn Emily Dickinson into their books willy-nilly. Mark Hofmann's decision to forge an Emily Dickinson poem doesn't, in itself, sound like the most significant aspect of the true crime mystery described above.

Deeply researched but with the narrative pace of a novel, Worrall’s investigation into the life and crimes of this charismatic genius is a real-life detective story you simply won’t be able to put down. On the way, you will meet an eclectic cast of characters: undercover detectives and rare book dealers, Dickinson scholars, forensic document experts, hypnotists, gun-dealers and Mormons ...

Still, each to their own. It certainly confirms the poet's ability to rouse strong passions: then and now.

Perhaps Emily's strongest mark to date, however, has been on the world of film and theatre. Julie Harris's award-winning performance in the long-running play "The Belle of Amherst" (broadcast live on TV in 1976 as a one-woman show), has been criticised by Lyndall Gordon for "perpetuating Mabel Loomis Todd's chaste, hermit-like image of Dickinson, as opposed to the lively, witty, provocative, and sometimes erotic Dickinson present in her work and known to those who knew her more personally."

At the time, though, at least one reviewer praised it as follows:

With her technical ability and her emotional range, Miss Harris can convey profound inner turmoil at the same time that she displays irrepressible gaiety of spirit.

Diagnosed with “Bright’s Disease”, a kidney ailment, [Emily's] health deteriorates with back pain and grand mal seizures. Mother, long suffering from melancholy, has a stroke and passes. Subsequently, Emily discovers that Austin is having an affair with a singer (Mrs Todd). Emily, with sympathy for Susan, confronts her brother’s hypocrisy. With the strains growing, Vinnie points out to Emily her own intolerance of the failings of others.And so it goes, I guess: Life's a bitch and then you die.

Emily’s condition deteriorates. She dies with Austin and Vinnie visibly distraught by her side.- Wikipedia: A Quiet Passion

Students of Terence Davies' work have been conditioned to respond favourably to his subtle, understated style. On the other hand, it can be criticised - especially latterly, in this and his follow-up film Benediction, about war poet Siegfried Sassoon - for, at times, taking understatement to the point of indirection.

The same could not be said of Madeleine Olnek's Wild Nights with Emily. As its star, Molly Shannon, explained to Entertainment Weekly:

"She’s perceived as a spinster recluse who wanted her poems burned upon death ... That story was fabricated ... She was a lively woman who 100 percent wanted to be published and went up against big men at the head of literary journals, [while] she had a love life — with her brother’s wife ..."Dirty - quiet - cheerful ... "Nature abhors a vaccuum" is a saying as old as the hills. Any attempts that Emily Dickinson may (or may not) have made to erase herself during her lifetime appear to have backfired with a vengeance.

Shannon referenced a 1998 New York Times article, which thanks to infrared light technology, was able to report that Susan's name had been erased from over 10 of Dickinson's writings. The actress seems overjoyed that this new movie will show Dickinson's love for Susan, as well as what Shannon believes was the poet's real personality: that of a woman "full of lust and passion."

"I don’t want to say she was 'dirty,' but she was a very passionate, hungry, deep, insightful, tuned in, expressive lover!"

Right now she seems to be pretty much "any type of dancer they wanted her to be," to quote (yet again) from my all-time favourite movie about the writing trade, Wonder Boys.

For myself, I find it a bit difficult to get past Hailee Steinfeld's star turn as Emily. Talk about mercurial moods and passions! This Emily gets to do - and say - it all. She's about as shy and retiring as Lady Gaga. And yet her melancholic turns make perfect dramatic sense as well.

For anyone who thought that her bravura performance in True Grit marked the apogee of her talent: think again. If the real Emily wasn't like this, she definitely should have been.

Emily in Paris, eat your heart out! Steinfeld's Emily in Amherst is not only a better writer than Lily Collins' fish-out-of-water in la ville lumière, she's also a snappier dresser. Who else could rock those mid-nineteenth-century frocks like she does? Even Death agrees, and he's a pretty stern critic ...

True, there may be a certain disconnect with the "creature" encountered by Thomas Higginson on his 1870 visit: the one with "smooth bands of red hair and no good features", but Hailee Steinfeld does her level best to dress down at least some of the time.

What matters is that this Emily is splendidly alive - and sassy. "She had said a lot of strange things, from which Higginson deduced an 'abnormal' life". But what he saw as abnormal we might feel inclined to see as living her best life.

Books I own are marked in bold:

- A Valentine [“‘Sic transit gloria mundi,’”]. Springfield Daily Republican (February 20, 1852)

- To Mrs -, with a Rose ["Nobody knows this little rose -”]. Springfield Daily Republican (August 2, 1858)

- The May-Wine [“I taste a liquor never brewed - ”]. Springfield Daily Republican (May 4, 1861)

- The Sleeping [“Safe in their Alabaster Chambers – ”]. Springfield Daily Republican (March 1, 1862)

- Sunset [“Blazing in Gold, and quenching in Purple” ]. Drum Beat (February 29, 1864)

- Flowers [“Flowers - Well - if anybody”]. Drum Beat (March 2, 1864)

- October [“These are the days when Birds come back -”]. Drum Beat (March 11, 1864)

- My Sabbath [“Some keep the Sabbath going to Church - ”]. Round Table (March 12, 1864)

- Success is counted sweetest. Brooklyn Daily Union (April 27, 1864)

- The Snake ["A narrow Fellow in the Grass”]. Springfield Daily Republican (February 14, 1866)

- Success is counted sweetest. A Masque of Poets (1878)

- Poems by Emily Dickinson. Edited by Two of Her Friends, Mabel Loomis Todd & T. W. Higginson (1890)

- Poems by Emily Dickinson: Second Series. Edited by Two of Her Friends, T. W. Higginson & Mabel Loomis Todd (1891)

- Poems by Emily Dickinson: Third Series. Edited by Two of Her Friends, T. W. Higginson & Mabel Loomis Todd (1896)

- The Single Hound: Poems of a Lifetime. Ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi (1914)

- The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, with an Introduction by Her Niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi (1924)

- Further Poems of Emily Dickinson. Withheld from Publication by Her Sister Lavinia. Ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi & Alfred Leete Hampson (1929)

- The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi & Alfred Leete Hampson (1930)

- Unpublished Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi & Alfred Leete Hampson (1935)

- Bolts of Melody: New Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Mabel Loomis Todd & Millicent Todd Bingham (1945)

- The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Including Variant Readings Critically Compared with All Known Manuscripts. 3 vols. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson (1955)

- The Complete Poems. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson. 1955. London: Faber, 1975.

- Emily Dickinson: Selected Poems & Letters. Ed. Robert N. Linscott (1959)

- Selected Poems & Letters. Together with Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s Account of His Correspondence with the Poet and His Visit to Her in Amherst. Ed. Robert N. Linscott. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1959.

- A Choice of Emily Dickinson's Verse. Ed. Ted Hughes (1968)

- A Choice of Emily Dickinson's Verse. Ed. Ted Hughes. 1968. London: Faber, 1970.

- The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson: A Facsimile Edition. 2 vols. Ed. R. W. Franklin (1981)

- The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition. 3 vols. Ed. R. W. Franklin (1998)

- The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition. 3 vols. Ed. R. W. Franklin. Cambridge, Mass & London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Emily Dickinson: The Gorgeous Nothings. Ed. Jen Bervin & Marta Werner (2013)

- The Gorgeous Nothings. Ed. Jen Bervin & Marta Werner. Preface by Susan Howe. New York: New Directions / Christine Burgin, in association with Granary Books, 2013.

- Envelope Poems. Ed. Jen Bervin & Marta Werner (2016)

- Envelope Poems. Ed. Jen Bervin & Marta Werner. New York: New Directions / Christine Burgin, 2016.

- Emily Dickinson's Poems: As She Preserved Them. Ed. Cristanne Miller (2016)

- Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them. Ed. Cristanne Miller. Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- A Valentine ["Magnum bonum, harem scarum”]. Amherst College Indicator (February, 1850)

- Letters of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols. Ed. Mabel Loomis Todd (1894)

- The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi (1924)

- Letters of Emily Dickinson: New and Enlarged Edition. Ed. Mabel Loomis Todd (1931)

- Emily Dickinson: Face to Face. Unpublished Letters with Notes and Reminiscence. Ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi (1932)

- Emily Dickinson's Letters to Dr. and Mrs. Josiah Gilbert Holland. Ed. Theodora Van Wagenen Ward (1951)

- Emily Dickinson: A Revelation. Ed. Millicent Todd Bingham (1954)

- The Letters of Emily Dickinson. 3 vols. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson & Theodora Ward (1958)

- Johnson, Thomas H., ed. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Associate Editor, Theodora Ward. 3 vols. 1958. Cambridge, Mass & London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1979.

- The Lyman Letters: New Light on Emily Dickinson and Her Family. Ed. Richard B. Sewall (1965)

- Open me carefully: Emily Dickinson's Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson. Ed. Ellen Louise Hart & Martha Nell Smith (1998)

- The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Cristanne Miller & Domhnall Mitchell (2024)

- The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Cristanne Miller & Domhnall Mitchell. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024.

- Bingham, Millicent Todd. Ancestor’s Brocades. The Literary Début of Emily Dickinson (1945)

- Ancestor’s Brocades. The Literary Discovery of Emily Dickinson: The Editing and Publication of Her Letters and Poems. 1945. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1967.

- Whicher, George. This Was a Poet: A Critical Biography of Emily Dickinson (1952)

- Bingham, Millicent Todd. Emily Dickinson’s Home: Letters of Edward Dickinson and His Family. (1955)

- Emily Dickinson’s Home: The Early Years, as Revealed in Family Correspondence and Reminiscences. With Documentation and Comment. 1955. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1967.

- Johnson, Thomas H. Emily Dickinson: An Interpretative Biography (1955)

- Emily Dickinson: An Interpretative Biography. 1955. New York: Atheneum, 1980.

- Leyda, Jay. The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols (1960)

- Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols (1974)

- Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson (2001)

- Gordon, Lyndall. Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family's Feuds (2010)

- Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family's Feuds. 2010. Virago Press. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 2010.

Poetry:

Letters:

Secondary:

There are, of course, many other sub-branches of Dickinsoniana: poetry selections (illustrated and unillustrated), facsimile editions, critical interpretations by the yard. One rather interesting aspect of this is her tendency to inspire children's picture books.

Here are a few examples:

"What if your neighbor were the reclusive poet Emily Dickinson? And what if one day she sent a letter inviting your mother to pay her a visit? A little girl who lives across the street from the mysterious Emily gets a chance to meet the poet when her mother goes to play the piano for her. There, the girl sneaks a gift up to Emily, who listens from the landing, and in return, Emily gives the girl a precious gift of her own — the gift of poetry."

"Eleven-year-old Suzy just can't win. Her brother is a local hero for calling 911 after seeing their elderly neighbor collapse, and only her best friend was able to win a role in the play they both auditioned for. Feeling cast aside from all angles, Suzy sees a kindred spirit in Emily Dickinson, the subject of her summer project. Suzy decides to escape from her disappointments by emulating the poet's life of solitude: no visitors or phone calls (only letters delivered through her window), no friends (except her goldfish, Ottilie), and no outings (except church, but only if she can wear her long white Emily dress)."

"Avid gardener and poet Emily Dickinson collected 424 pressed flower specimens and wrote nearly 1800 poems in her lifetime, with nature and plants inspiring many of her beloved works. Lines and couplets from Dickinson’s poems paired with Carme Lemniscates’ gorgeous illustrations bring In Emily’s Garden to life, letting toddlers take a stroll in Emily’s garden of verses. See the flowers, birds, butterflies, and bees through Emily’s eyes, and foster a love of gardens and poems alike."

"As a young girl, Emily Dickinson loved to scribble curlicues and circles, imagine new rhymes, and connect with the natural world around her. The sounds, sights, and smells of home swirled through her mind, and Emily began to explore writing and rhyming her thoughts and impressions. She thinks about the real and the unreal. Perhaps poems are the in-between."

"In a small New England town lives Emily Dickinson, a girl in love with small things — a flower petal, a bird, a ray of light, a word. In those small things, her brilliant imagination can see the wide world — and in her words, she takes wing. From celebrated children's author Jennifer Berne comes a lyrical and lovely account of the life of Emily Dickinson: her courage, her faith, and her gift to the world. With Dickinson's own inimitable poetry woven throughout, this lyrical biography is not just a tale of prodigious talent, but also of the power we have to transform ourselves and to reach one another when we speak from the soul."

"In Becoming Emily, young readers will learn how as a child, adolescent, and well into adulthood, Dickinson was a lively social being with a warm family life. Highly educated for a girl of her era, she was fully engaged in both the academic and social aspects of the schools she attended until she was nearly 18. Her family and friends were of the utmost importance to her, and she was a prolific, thoughtful, and witty correspondent who shared many poems with those closest to her. Including plentiful photos, full-length poems, letter excerpts, a time line, source notes, and a bibliography, this indispensable resource offers a full portrait of this singular American poet."

"Follow along as we delve into Emily Dickinson’s childhood, revealing a young girl desperate to go out exploring―to meet the flowers in their own homes. Wade through tall grasses to gather butterfly weed and goldenrod, the air alive with the 'buccaneers of buzz.' And, don’t forget to keep a hot potato in your pocket to keep your fingers warm.

This is Emily Dickinson as you’ve never seen her before, embarking on an unforgettable journey in her hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts, with her trusty four-legged companion, Carlo."

•