D. I. B. Smith (1934-2023)

D. I. B. Smith (1934-2023)[photograph courtesy of Caitlin Smith]

i. m. Emeritus Professor Donal Ian Brice Smith

(4/2/1934 - 27/9/2023)

I don't think I ever had a conversation with Don Smith which didn't end in some interesting book recommendation - or else a new insight into a long-beloved classic. He was the first Academic I ever met who seemed to be driven solely by a love for books and reading in general. "Great stuff!" he would intone, as he leafed through another shabby-looking prize from the second-hand bookshops downtown.

I was somewhat in awe of him to start with - and for quite a long time after that. I had, for some unaccountable reason, decided in the early 1980s that it was up to me to reclaim from oblivion the long-neglected novels of British Poet Laureate John Masefield by composing a Master's thesis about them.

"How many novels did he actually write?" asked one of the prospective supervisors I approached. "Twenty-three," I replied. "And how many of them have you read?" "Twenty-three." [1] Strangely enough, that particular prospect discovered he had urgent duties elsewhere and could not accept a new research student at that time ...

Don - or 'Professor Smith', as I continued to address him till long after I had ceased to be his student - actually was far too busy to take me on. He was, after all, Head of Department at the time. But when I went to see him about it, he said that he would do it - but only if nobody else was able to.

Which left me with the somewhat invidious task of visiting each and every one of the Academics in the of the University of Auckland English Department who might conceivably be interested in such a project. It was certainly very educational to sample the variety of excuses they came up with - from the straight 'no' to the 'maybe some other time' to the 'perhaps if you changed it to ... [something quite unrelated].'

But no, I was - no doubt foolishly - quite determined, so I eventually made my way back to Don's door, and to his somewhat reluctant oversight ...

How did he approach it? He sat there and talked, while I took notes. His talk ranged over many subjects, some relevant and others perhaps not quite so relevant. At the time I recall he was reading the work of Anglo-Irish writer Shane Leslie - who was pretty obscure even by my standards - as well as working on some of the lesser known novels of Ezra Pound's early mentor (and Joseph Conrad's collaborator) Ford Madox Ford.

Was any of this relevant to Masefield? Well, in a curious way, as it turned out, yes. The interface between the 'commercial' and the 'literary' faces of Edwardian literature fitted rather nicely into studying the work of a poet, Masefield, who was publishing at the same time as Eliot and Pound, but inhabited a world almost literally invisible to their admirers. Ford was a good example of the same phenomenon, though in a rather different way.

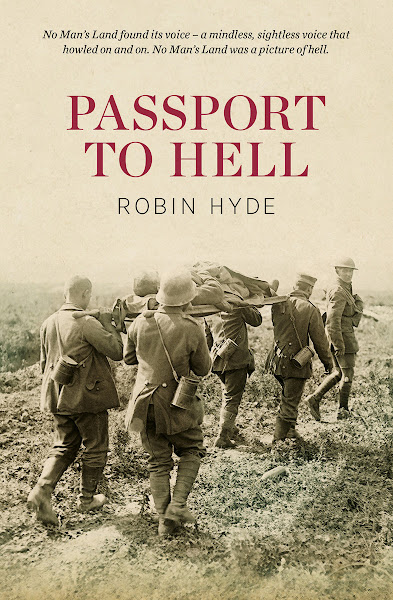

Don's original field of specialisation had been seventeenth century literature. He'd published an edition of Andrew Marvell's satirical prose work The Rehearsal Transpros'd in the Oxford English Texts series. When I asked him about this, he said, "Well, it got me this job." What he seemed to like most, though, was exploring the more offbeat byways of Anglo-Irish literature - not to mention New Zealand writers such as Robin Hyde: far less well-known then than she is now.

The more I heard from him, the more I liked it. I'd been trained in my undergraduate career to admire such extreme Modernists as Eliot and Joyce, and this (still) makes perfect sense to me. On the other hand, there was a rich penumbra of weirdos such as Chesterton and de la Mare, whom I liked just as much, but whom I'd been encouraged to dismiss as dead ends in the grand obstacle race of literary innovation.

Don wasn't interested in any of that survival-of-the-fittest nonsense. Is it enjoyable? was his central criterion for a book. Yes, he was certainly interested in the finesse and skill behind particular pieces of writing, but he still seemed to steer instinctively towards the anecdotal and - above all - towards enthusiasm in his approach to what he read.

I resolved to do likewise, and so, much later, when I in my turn became an English Academic with my own graduate students, I tried to give them as much as possible of the same formula: Read the book, not - till much later - the secondary literature about it. If you don't like it, acknowledge the fact - but then try and work out why.

It is, I suppose, an approach designed to produce readers, not students or teachers of literature. But then, if you don't actually get a kick out of the stuff you read, you probably shouldn't be teaching the subject in the first place.

That was the first - and probably the most important - of my many, many debts to Don.

Most prominent among the others would have to be the innumerable letters of recommendation he wrote for me while I was undertaking my long and arduous quest for an actual job in the fields of Academia. Once again, I've tried to follow his good example when asked to do the same thing for my ex-students.

But then I could never have got that far in the first place if I hadn't got a scholarship to study overseas, and I doubt very much that that would have happened without his powerful advocacy.

What else? Well, after he retired, I visited him a few times at his wonderful house in Mission Bay, and admired the cupboard where he kept his very extensive collection of Sci-fi and Fantasy literature. That was another subject on which we saw eye to eye (for the most part). He had what seemed to me an inexplicable enthusiasm for Andre Norton, whereas I was more attuned to Philip K. Dick and Samuel R. Delany, but there was generally some new fantasy epic he'd been reading which I ended up making a mental note to get hold of as soon as I could.

He made all them sound like so much fun - though he did stray into heresy on one occasion, I recall, by claiming to prefer Tad Williams to J. R. R. Tolkien as a writer of epic fantasy. This was, as I solemnly informed him, a little like preferring some latter-day SF luminary to Arthur C. Clarke - if they're able to see further, it's because they're standing on giant shoulders ...

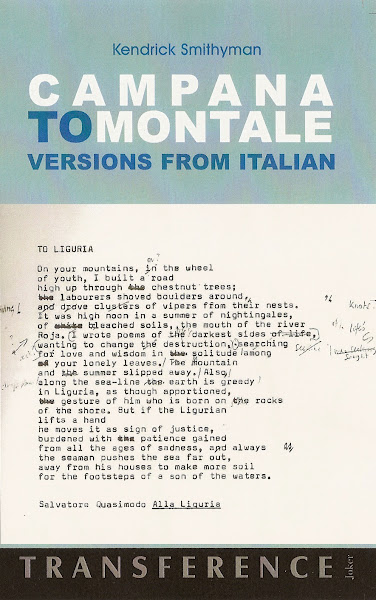

He knew I was passionate about the poetry of our Auckland University colleague Kendrick Smithyman, and since Don and I could both read Italian, he lent me the typescript of some versions the monolingual Smithyman had concocted of certain modern Italian poets through the medium of other people's translations.

That, too, was a precious gift. I ended up editing and publishing the entire collection, which still seems to me - like Pound's Cathay - to prove that the end result of a process of translation counts for far more than the way that a writer actually gets there. Kendrick's versions from Italian have a supple ease and charm which far better linguists than he have tried in vain to achieve - and, in the process, he found in the poet Salvatore Quasimodo a virtual alter ego.

I was also presumptuous enough to ask Don to launch my first novel, Nights with Giordano Bruno, which he did with great style and panache. I remember he compared it to Mario Praz's famous critical book The Romantic Agony, which is, I'm sure, far more credit than it deserved. It was characteristic of his ready wit as well as his charity, though.

Another of my favourite memories of him is the time he hunted me down at my student lodgings in Edinburgh and took me out to dinner at a local tratteria called Pinocchio's. It was wonderful to see him en famille, with his wife Jill and daughter Caitlin, and - as I recall - a great deal of red wine was drunk and pasta eaten in the course of the evening!

As Stephen King's writer hero says of his friend in the movie Stand by Me: "I'll miss him forever." That's certainly true. I'd love to have another of those wonderful, unexpected conversations where Don Smith turned all my prejudices and presuppositions on their heads. But in another, realer sense he's not dead - he'll never be dead.

I can hear him now saying "Great stuff" and reading out another passage from his latest essay, where he juxtaposes a quote from Ford Madox Ford about his latest drivelly historical romance The Young Lovell with another precisely contemporary set of Fordian instructions on how to be absolutely modern to his errant young protégé Ezra Pound ... [2]

Notes:

1. You can find them all listed here, at https://madbookcollection.blogspot.com/2009/04/acquisitions-86-john-masefield.html - if you're curious.2. Arthur Rimbaud, "Il faut être absolument moderne." Une Saison en enfer (1873). Pound said of Ford Madox Ford in his 1939 obituary:[H]e felt the errors of contemporary style to the point of rolling (physically, and if you look at it as mere snob, ridiculously) on the floor of his temporary quarters in Giessen when my third volume displayed me trapped, fly-papered, gummed and strapped down in a jejune provincial effort to learn ... the stilted language that then passed for 'good English' ...

And that roll saved me two years, perhaps more. It sent me back to my own proper effort, namely, toward using the living tongue ... though none of us has found a more natural language than Ford did.

•