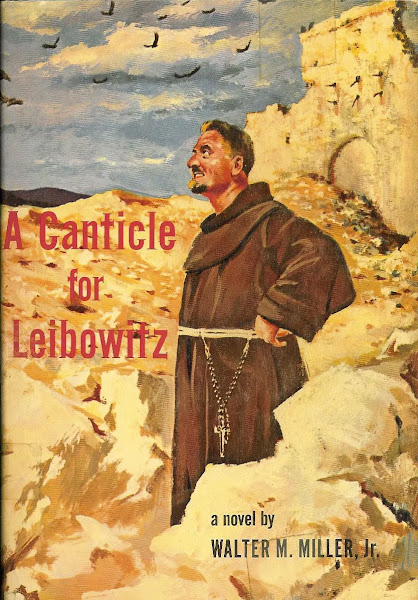

Ever since I first picked up a scruffy secondhand paperback copy in a local bookshop, I've been entranced by A Canticle for Leibowitz. As you can see from the montage below, there's been no shortage of editions and reprints of this 'famous and prophetic best seller of the new dark age of man". What of its author, though? Who was this strange man Walter M. Miller, Jr.?

Well, as W. H. Auden states so succinctly in his sonnet Who's Who: "A shilling life will give you all the facts" - or, as in this case, a brief consultation of the relevant wikipedia entry:

Miller was born on January 23, 1923, in New Smyrna Beach, Florida. Educated at the University of Tennessee and the University of Texas, he worked as an engineer. During World War II, he served in the Army Air Forces as a radioman and tail gunner, flying more than fifty bombing missions over Italy. He took part in the bombing of the Benedictine Abbey at Monte Cassino, which proved a traumatic experience for him. Joe Haldeman reported that Miller "had post-traumatic stress disorder for 30 years before it had a name"

Joe Haldeman is, of course, the author of the classic Vietnam-cum-SF novel The Forever War, still in print after almost fifty years.

After the war, Miller converted to Catholicism ... Between 1951 and 1957, [he] published over three dozen science fiction short stories, winning a Hugo Award in 1955 for the story "The Darfsteller".

Late in the 1950s, Miller assembled a novel from three closely related novellas he had published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in 1955, 1956 and 1957. The novel, entitled A Canticle for Leibowitz, was published in 1959. It is a post-apocalyptic novel revolving around the canonisation of Saint Leibowitz, and is considered a masterpiece of the genre. It won the 1961 Hugo Award for Best Novel.

After the success of A Canticle for Leibowitz, Miller ceased publishing, although several compilations of Miller's earlier stories were issued in the 1960s and 1970s.

In Miller's later years, he became a recluse, avoiding contact with nearly everyone, including family members; he never allowed his literary agent, Don Congdon, to meet him. According to science fiction writer Terry Bisson, Miller struggled with depression, but had managed to nearly complete a 600-page manuscript for the sequel to Canticle before taking his own life with a firearm on January 9, 1996, shortly after his wife's death.

The sequel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, was completed by Bisson at Miller's request and published in 1997.

I wish I could say that this last, posthumous work of fiction was a triumphant vindication of his decades in the wilderness. Alas, it is not. Various of the commentators on his Goodreads page do their best to defend it:

[Dropping Out]: Miller's "problem" was that he hit a grand-slam home-run in Canticle, and he spent the remainder of what must have been a sad and frustrating life trying to get out from under Canticle's shadow. ...Others seem more inclined to tell it like it is:

[Jason]: Saint Leibowitz reminded me very much of Herbert's Dune. They are both sprawling novels dealing with the political machinations of both Church and State, and they both center on the manipulations of the mysterious, isolated, less-civilized nomadic peoples whose loyalties will tip the balance of power.

[Doreen]: Oddly enough, I seem to be one of the few people here who enjoyed the sequel much more than its predecessor. I found A Canticle... devoid of much of the human suffering that pervades this book, which questions the conflict between faith and tradition, desire and happiness, and what it means to be a good human being.

[Bryn Hammond]: There’s almost no science fiction left. It was much more like reading a (burlesque) historical fiction on the medieval church, muddled up with the American West. Canticle’s concerns with science aren’t pursued, and the post-nuclear-war setting becomes accidental.Perhaps the best overall summary comes from Zoe's Human:

[Jon]: The sequel to A Canticle for Leibowitz was thirty years in the making, but unfortunately, Miller seems to have forgotten how to write a novel in those decades. Many of the moral and ethical arguments that made Canticle so brilliant are still present, as is the occasional bit of dry humor, but these are overshadowed by long and drawn-out passages, poor plotting, and a conclusion that seems to have been hastily written the night before the book went to press (the "Wild Horse Woman" from the title, for example, virtually never appears in the novel; I'm still confused as to why her name appears so prominently on the book's spine)

Life is too short for books you don't enjoy.

Maybe the fault is mine for trying to read this right after A Canticle for Leibowitz which would be a tough act to follow for anyone (including, apparently, the author who wrote it). Perhaps my expectations were just too high. This started off well enough with a nice premise about loss of faith, but it kind of fizzled after the first two or three chapters.

Or perhaps the fact that the author was suicidally depressed and took his own life before he finished it was a factor. Another author finished it from a reportedly almost complete manuscript, but how complete was it really? And how much did the original author's struggle with mental illness factor in?

One of Miller's rarer stories, not included in any of the various collections of his short fiction, is "Izzard and the Membrane." An extra level of confusion is added by the fact that the book above, which I inherited from my father's science fiction collection, is the 1953 UK edition of a book which originally appeared in the USA in 1952. Despite its publication date, then, it actually constitutes The Year's Best Science Fiction Novels 1952, not 1953:

The American edition also included an extra story, Arthur C. Clarke's "Seeker of the Sphinx", presumably omitted from the British reprint for copyright reasons.

The reason this bibliographical minutiae seems worth stressing is because "Izzard and the Membrane" is quite a remarkable story, every bit the equal of most of the novellas included in his officially sanctioned collections. Its cold war stereotypes may be a little dated now, but Miller's astonishing intuitions about the possibilities of computer artificial intelligence and the creation of alternate realities are worthy of the creators of Westworld or the Metaverse itself.

So good is it, in fact, that it makes one feel rather curious about some of the other stories I've tried to list below as comprehensively as possible. By my count he wrote 43 stories in all (at least two of which were not SF). Of these 41, a mere fourteen were collected in his final selection The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1980) - subsequently reprinted under other titles, but without any expansion of the contents.

That leaves at least 26 other stories to read (not counting the two romance stories and a co-authored crime story) from that incredibly productive period of writing between 1951 and 1957. There may well be some duds among them, but it seems hard to believe that only "Izzard" is worthy of resurrection among such a number of pieces published - for the most part - in the top SF journals of the day.

That's the new Walter M. Miller book I'm holding out for: not the last, incomplete, rather depressing Saint Leibowitz. After all, his short stories and short novels were always his strongest work. From the much-anthologised "Crucifixus Etiam," with its unforgettable image of the purgatorial plains of Mars, to ,"Big Joe and the Nth Generation" (aka "It Takes a Thief"), he showed a flair for memorable characterisation and arresting plotlines second to none - not even such celebrated contemporaries as Philip K. Dick and Robert A. Heinlein.

That's not to say that there was anything unprecedented about Miller's trajectory from slam-bang Sci-fi to the subtleties of religious dogma in the apocalypse-haunted 1950s. It wasn't just mainstream fiction which had become obsessed with the ethical dilemmas associated with (mainly Catholic) Christianity. Authors such as Graham Greene, François Mauriac and Evelyn Waugh dominated the bestseller lists, and it seemed for a while there as if the twin blows of Hiroshima and Auschwitz had discredited scientific reductionism for good.

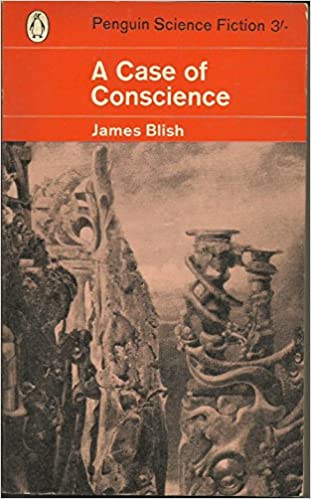

James Blish's A Case of Conscience is a good example - within the strict genre-boundaries of SF - of this type of writing. It could apparently then be taken for granted that monastic orders would accompany any future space-faring expeditions, and that the local religious concerns of this world were bound to find echoes out in the great beyond.

C. S. Lewis's interplanetary trilogy undoubtedly helped to demonstrate the viability of such themes in a genre still dominated by the rationalist assumptions of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Ray Bradbury got in on the act, too, in his story "The Fire Balloons" [aka "In This Sign ..."] included in some editions of his classic Martian Chronicles.

In a way, though, despite his obvious affinity with other such earnest Catholic strivers in the 1950s, the sheer philosophical scope of Miller's Canticle seems to me to have more in common with Hermann Hesse's Glass Bead Game (1943) than with the likes of Blish, Bradbury or Lewis.

Its popularity then and since has undoubtedly depended to some extent on its links with other SF apocalypses of the 1950s: George Stewart's Earth Abides (1949), or Philip K. Dick's zany Dr Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb (1965). A Canticle for Leibowitz continues to evade us, though. It has elements of all of these things - Catholic apologia, SF Apocalypse, Dystopian satire - and yet it can't be said to be subsumed entirely by any of them.

I do hope one day to be able to purchase at least some of the uncollected stories of Walter M. Miller in convenient book form, but there's certainly a strong case for believing that everything significant he had to say was contained in this one, stand-alone masterpiece. His mistake, then - if mistake it was - lay in thinking he could emulate or even surpass it in his final few years.

-

Novels:

- A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)

- Fiat Homo [aka 'A Canticle for Leibowitz'] (1955)

- Fiat Lux [aka 'And the Light is Risen'] (1956)

- Fiat Voluntas Tua [aka 'The Last Canticle'] (1957)

- A Canticle for Leibowitz: A Novel. 1959. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1960.

- A Canticle for Leibowitz. 1959. Corgi Science-Fiction. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1970.

- [with Terry Bisson] Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman (1997)

- Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman. Ed. Terry Bisson. 1997. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 1998.

- The Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels. Ed. Everett F. Bleiler & T. E. Dikty. London: Grayson & Grayson, 1953.

- Izzard and the Membrane, by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

- … And Then There Were None, by Eric Frank Russell

- Flight to Forever, by Poul Anderson

- The Hunting Season, by Frank M. Robinson

- Conditionally Human (1962)

- Conditionally Human (1952)

- The Darfsteller (1955)

- Dark Benediction (1951)

- The View from the Stars (1965)

- Blood Bank (1952)

- Dumb Waiter (1952)

- Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)

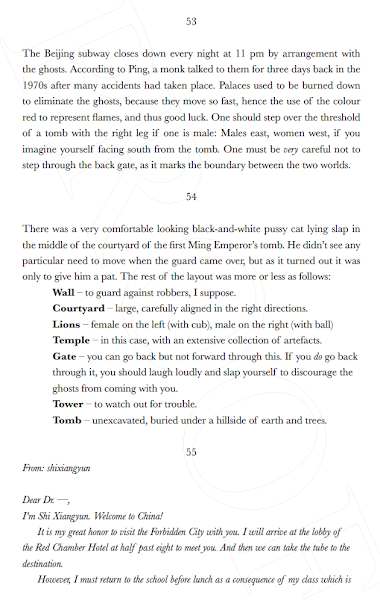

- The Big Hunger (1952)

- The Will (1954)

- Crucifixus Etiam (1953)

- I, Dreamer (1953)

- Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)

- You Triflin' Skunk! (1955)

- The Science Fiction Stories of Walter M. Miller Jr. (1977)

- Conditionally Human (1952)

- Blood Bank (1952)

- Dark Benediction (1951)

- Dumb Waiter (1952)

- Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)

- The Big Hunger (1952)

- The Darfsteller (1955)

- The Will (1954)

- Crucifixus Etiam (1953)

- I, Dreamer (1953)

- Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)

- You Triflin' Skunk! (1955)

- Conditionally Human and Other Stories. 1980. Corgi Science-Fiction. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1982.

- Conditionally Human (1952)

- Blood Bank (1952)

- Dark Benediction (1951)

- Dumb Waiter (1952)

- Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)

- The Big Hunger (1952)

- The Darfsteller and Other Stories. 1980. Corgi Science-Fiction. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1982.

- The Darfsteller (1955)

- The Will (1954)

- Vengeance for Nikolai (1957)

- Crucifixus Etiam (1953)

- I, Dreamer (1953)

- The Lineman (1957)

- Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)

- You Triflin' Skunk! (1955)

- Dark Benediction. [aka 'The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr.', 1980]. SF Masterworks. Gollancz. London: Orion Publishing Group, 2007.

- Conditionally Human (1952)

- Blood Bank (1952)

- Dark Benediction (1951)

- Dumb Waiter (1952)

- Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)

- The Big Hunger (1952)

- The Darfsteller (1955)

- The Will (1954)

- Vengeance for Nikolai (1957)

- Crucifixus Etiam (1953)

- I, Dreamer (1953)

- The Lineman (1957)

- Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)

- You Triflin' Skunk! (1955)

- Two Worlds of Walter M. Miller (2010)

- The Hoofer (1955)

- Death of a Spaceman (1954)

- The Hoofer [1955] (2009)

- Death of a Spaceman [1954] (2009)

- Way of a Rebel [1954] (2010)

- Check and Checkmate [1953] (2010)

- The Ties That Bind [1954] (2010)

- Conditionally Human [1952] (2016)

- It Takes a Thief [1952] (2019)

- MacDoughal's Wife [not SF] (1950)

- Month of Mary [not SF] (1950)

- Secret of the Death Dome [novella] (1951)

- Izzard and the Membrane [novella] (1951)

- The Soul-Empty Ones [novella] (1951)

- Dark Benediction [novella] (1951)

- The Space Witch [novella] (1951)

- The Song of Vorhu ... for Trumpet and Kettledrum [novella] (1951)

- The Little Creeps [novella] (1951)

- The Reluctant Traitor [novella] (1952)

- Conditionally Human [novella] (1952)

- Bitter Victory (1952)

- Dumb Waiter [novella] (1952)

- Big Joe and the Nth Generation {aka "It Takes a Thief"} (1952)

- Blood Bank [novella] (1952)

- Six and Ten Are Johnny [novella] (1952)

- Let My People Go [novella] (1952)

- Cold Awakening [novella] (1952)

- Please Me Plus Three [novella] (1952)

- No Moon for Me (1952)

- The Big Hunger (1952)

- Gravesong (1952)

- Anybody Else Like Me? {aka "Command Performance"} [novella] (1952)

- A Family Matter (1952)

- Check and Checkmate [novella] (1953)

- Crucifixus Etiam {aka "The Sower Does Not Reap"} (1953)

- I, Dreamer (1953)

- The Yokel [novella] (1953)

- Wolf Pack (1953)

- The Will (1954)

- Death of a Spaceman {aka "Memento Homo"} (1954)

- I Made You (1954)

- Way of a Rebel (1954)

- The Ties that Bind [novella] (1954)

- The Darfsteller [novella] (1955)

- You Triflin' Skunk! {aka "The Triflin' Man"} (1955)

- A Canticle for Leibowitz {aka "The First Canticle"} [novella] (1955)

- The Hoofer (1955)

- And the Light is Risen [novella] (1956)

- The Last Canticle [novella] (1957)

- Vengeance for Nikolai {aka "The Song of Marya"} (1957)

- [with Lincoln Boone] The Corpse in Your Bed is Me (1957)

- The Lineman [novella] (1957)

- David N. Samuelson, "The Lost Canticles of Walter M. Miller, Jr." Science Fiction Studies #8 (Vol 3, part 1) (March 1976) - "Appendix: The Books and Stories of Walter M. Miller, Jr.":

- "Secret of the Death Dome," novelette, Amazing (January, 1951; reprinted in Amazing (June, 1966).

- "Izzard and the Membrane," novelette, Astounding (May, 1951); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels: 1952 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1952).

- "The Soul-Empty Ones," novelette, Astounding (August, 1951).

- "Dark Benediction," short novel, Fantastic Adventures (September, 1951); collected in Conditionally Human (1962).

- "The Space Witch," novelette, Amazing (November, 1951); reprinted in Amazing (October, 1966).

- "The Song of Vorhu ... for Trumpet and Kettledrum," novelette, Thrilling Wonder Stories (December, 1951).

- "The Little Creeps," novelette, Amazing (December, 1951); reprinted in Fantastic (May, 1968); anthologized in Milton Lesser, ed., Looking Forward (New York: Beechhurst, 1953).

- "The Reluctant Traitor," short novel, Amazing (January, 1952).

- "Conditionally Human," novelette, Galaxy (February, 1952); revised and collected in Conditionally Human (1962); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels: 1953 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1953).

- "Bitter Victory," short story, IF (March, 1952).

- "Dumb Waiter," novelette, Astounding (April, 1952); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Groff Conklin, ed., Science Fiction Thinking Machines (New York: Vanguard, 1954) and Damon Knight, Cities of Wonder (Garden City: Doubleday, 1966).

- "It Takes a Thief," short story, IF (May, 1952); collected, as "Big Joe and the Nth Generation," in The View from the Stars (1965).

- "Blood Bank," novelette, Astounding (June, 1952); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Martin Greenberg, ed., All About the Future (New York: Gnome Press, 1953).

- "Six and Ten are Johnny," novelette, Fantastic (Summer, 1952); reprinted in Fantastic (January, 1966).

- "Let My People Go," short novel, IF (July, 1952).

- "Cold Awakening," novelette, Astounding (August, 1952).

- "Please Me Plus Three," novelette, Other Worlds (August, 1952).

- "No Moon for Me," short story, Astounding (September, 1952); anthologized in William Sloane, ed., Space, Space, Space (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1953).

- "The Big Hunger," short story, Astounding (October, 1952); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Donald A Wollheim, ed., Prize Science Fiction (New York: McBride, 1953).

- "Gravesong," short story, Startling (October, 1952).

- "Command Performance," novelette, Galaxy (November, 1952); collected, as "Anybody Else Like Me?" in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1953 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1953); Horace Gold, ed., The Second Galaxy Reader (New York: Crown, 1954); and Brian W. Aldiss, ed., Penguin Science Fiction (London: Penguin, 1961).

- "A Family Matter," short story, Fantastic Story Magazine (November, 1952).

- "Check and Checkmate," novelette, IF (January, 1953).

- "Crucifixus Etiam," short story, Astounding (February, 1953); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1954 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1954); Judith Merril, ed., Human? (New York: Lion, 1954); Michael Sissons, ed., Asleep in Armageddon (London: Panther, 1962); Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest, eds., Spectrum V (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1966); and Robert Silverberg, ed., Tomorrow’s Worlds (New York: Meredith, 1969).

- "I, Dreamer," short story, Amazing (July, 1953); collected in The View from the Stars (1965).

- "The Yokel," novelette, Amazing (September, 1953).

- "The Wolf Pack," short story, Fantastic (Oct., 1953); reprinted in Fantastic (May, 1966); anthologized in Judith Merril, ed., Beyond the Barriers of Space and Time (New York: Random House, 1954).

- "The Will," short story, Fantastic (February, 1954); reprinted in Fantastic (April, 1969); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in T.E. Dikty, ed., The Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels: 1955 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1955).

- "Death of a Spaceman," short story, Amazing (March, 1954); reprinted in Amazing (March, 1969); anthologized in William F. Nolan, ed., A Wilderness of Stars (Los Angeles: Sherbourne Press, 1971); anthologized as "Memento Homo" in T.E. Dikty, ed., The Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels: 1955 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1955); Robert P. Mills, ed., The Worlds of Science Fiction (New York: Dial Press, 1963); and Laurence M. Janifer, ed., Masters’ Choice (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966).

- "I Made You," short story, Astounding (March, 1954).

- "Way of a Rebel," short story, IF (April, 1954).

- "The Ties that Bind," novelette, IF (May, 1954); anthologized in William F. Nolan, ed., A Sea of Space (New York: Bantam, 1970).

- "The Darfsteller," short novel, Astounding (January, 1955); collected in Conditionally Human (1962); anthologized in Isaac Asimov, ed., The Hugo Winners (Garden City: Doubleday, 1962).

- "The Triflin’ Man," short story, Fantastic Universe (January, 1955); collected as "You Triflin’ Skunk" in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Judith Merril, ed., Galaxy of Ghouls (New York: Lion, 1955).

- "A Canticle for Leibowitz," short novel, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F & SF) (April, 1955); revised as part of A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959); anthologized in T.E. Dikty, ed., Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels: 1956 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1956); Anthony Boucher, ed., The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, fifth series (Garden City: Doubleday, 1956); and Christopher Cerf, ed., The Vintage Anthology of Science Fantasy (New York: Vintage, 1966).

- "The Hoofer," short story, Fantastic Universe (September, 1955); anthologized in Judith Merril, ed., S_F: The Year’s Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy (New York: Dell, 1956), and S-F: The Best of the Best (New York: Dell, 1968).

- "And the Light is Risen," short novel, F & SF (August, 1956); revised as part of A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959).

- "The Last Canticle," short novel, F & SF (February, 1957); revised as part of A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959).

- "Vengeance for Nikolai," short story, Venture (March, 1957); anthologized in Joseph Ferman, ed., No Limits (New York: Ballantine, 1958).

- "The Corpse in Your Bed is Me," short story co-authored by Lincoln Boone, Venture (May, 1957).

- "The Lineman," short novel, F & SF (August, 1957); anthologized in William F. Nolan, ed., A Wilderness of Stars (Los Angeles: Sherbourne Press, 1971).

Collections:

Chapbooks:

Short Stories & Novellas:

[Included in The Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels (1952);

A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959);

Conditionally Human (1962);

The View from the Stars (1965);

The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1980);

Two Worlds of Walter M. Miller (2010)]

Secondary:

•