As the author of satirical campus novel The Annotated Tree Worship, it's perhaps not surprising that I take a lively interest in the subject of annotated editions of classic (or not-so-classic) texts.

I've written a number of posts on the subject already: one on which books I myself would be interested in annotating; another on the various competing annotated editions of Bram Stoker's Dracula; and yet another on The Annotated Arabian Nights, a project I would have dearly loved to undertake myself if I'd had the necessary linguistic equipment for it.

As well as that, I've put up some posts in the "Acquisitions" section of my bibliographical blog, A Gentle Madness, which provide listings of the various series of Annotated Editions I've come across to date:

- Clarkson N. Potter (17 titles: 1960-1986)

- Longman's Annotated English Poets (19 titles: 1965- )

- Landmark Ancient Histories (6 titles: 1996- )

- The Annotated Jane Austen (6 titles: 2004-2017)

- W. W. Norton (21 titles: 1999-2021)

- Harvard University's Belknap Press (23 titles: 2009-2022)

As well as these major series, there are a number of short runs and one-off titles I've encountered at various times, which I've grouped together below under "Miscellaneous".

I've arranged the books further as follows:

Why? What's the attraction of this particular sideline of literature? I suppose the initial impulse came from repeated readings of Martin Gardner's brilliant tour-de force The Annotated Alice. Alfred J. Appel's Annotated Lolita, too, made me feel as if I'd never really read Nabokov's novel before, so much of its subtext and larger implications had I apparently missed.

It took me a while to work out that there was no magic formula to the art of compiling an annotated edition. A pedestrian mind produces a dull jog-trot of a book, whereas a dazzling intellect (such as Gardner's or Appel's) can illuminate the murkiest depths of even the most apparently straightforward texts. By then, though, I was well down the road of collecting as many of them as I could find.

I don't regret the quest. It's been instructive. Even Gardner nods, to be honest. Few of his other annotated books read the heights of his Alice or his Snark (in their various revised and expanded versions). But they're always intriguing and thought-provoking.

I'm not sure that the same could be said of all the annotators listed below - some of them scarcely rise above the level of a set of hyperlinked references to Wikipedia; others are scholars as ingenious as Gardner at his best. You'll have to judge for yourselves which is which.

Oh, and one more thing: I've learned that - for me, at any rate - the best way to read an annotated edition is not to pause at every marginal note. That destroys the flow of the original text. I read straight through the equivalent of a chapter or so, and then go back and read all the notes for those pages. It may sound unwieldy, but it means that you can enjoy the book and savour the eccentricities of the annotator's peculiar mind (virtually all annotators seem to be eccentrics of one type or another: I wonder why?).

You may (or may not) find this useful advice. If you've already evolved your own system for reading these somewhat unwieldy tomes, feel free to ignore it. Just be aware that - like all the diverse ways we engage with texts - this one takes a bit of practice before it becomes second nature.

[NB: The rest of this post consists of long lists of hyperlinked texts with illustrations, so you may want to skip it if bibliographic minutiae are not really your bag.]

Books I own are marked in bold:

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice, ed. Martin Gardner (1960)

- Anon.: The Annotated Mother Goose, ed. William S. Baring-Gould & Ceil Baring-Gould (1962)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Snark, ed. Martin Gardner (1962)

- Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern (1964)

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge: The Annotated Ancient Mariner, ed. Martin Gardner (1965)

- Ernest Lawrence Thayer: The Annotated Casey at the Bat, ed. Martin Gardner (1967)

- The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. William S. Baring-Gould, 2 vols (1967)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Early Holmes (c. 1874-1887)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes (c.1889-1914)

- Henry D. Thoreau: The Annotated Walden, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern (1970)

- L. Frank Baum: The Annotated Wizard of Oz, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1973)

- Bram Stoker: The Annotated Dracula, ed. Leonard Wolf (1975)

- Charles Dickens: The Annotated Christmas Carol, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1977)

- Mary Shelley: The Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Leonard Wolf (1977)

- The Annotated Shakespeare, ed. A. L. Rowse, 3 vols (1978)

- William Shakespeare: Comedies

- William Shakespeare: Histories and Poems

- William Shakespeare: Tragedies and Romances

- Jonathan Swift: The Annotated Gulliver’s Travels, ed. Isaac Asimov (1980)

- Mark Twain: The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1981)

- Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Oscar Wilde, ed. H. Montgomery Hyde (1982)

- The Annotated Dickens, ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins, 2 vols (1986)

- Charles Dickens: The Pickwick Papers / Oliver Twist / A Christmas Carol / Hard Times

- Charles Dickens: David Copperfield / A Tale of Two Cities / Great Expectations

- Matthew Arnold: The Poems, ed. Kenneth Allott (1965)

- John Milton: Paradise Lost, ed. Alastair Fowler (1968)

- John Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. John Carey (1968)

- Thomas Gray, William Collins & Oliver Goldsmith: The Poems, ed. Roger Lonsdale (1969)

- Alfred Tennyson: The Poems, ed. Christopher Ricks (1969)

- John Keats: The Poems, ed. Miriam Allott (1970)

- William Blake: The Poems, ed. W. H. Stevenson & David Erdman (1972)

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene, ed. A. C. Hamilton (1977)

- Alfred Tennyson: The Poems: Revised Edition, 3 vols, ed. Christopher Ricks (1987)

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Poems [6 vols], ed. Kelvin Everest & Geoffrey Matthews (1989-2024)

- Robert Browning: The Poems [c. 7 vols], ed. John Woolford, Daniel Karlin & Joseph Phelan (1991- / 2010)

- John Dryden: The Poems [5 vols], ed. Paul Hammond & David Hopkins (1995-2005 / 2007)

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene: Revised Edition, ed. Hiroshi Yamashita & Toshiyuki Suzuki (2001)

- Andrew Marvell: The Poems, ed. Nigel Smith (2003)

- Alexander Pope: The Poems [c. 6 vols], ed. Julian Ferraro & Paul Baines (2007- )

- John Donne: The Complete Poems, ed. Robin Robbins (2010)

- William Shakespeare: The Complete Poems, ed. Cathy Shrank & Raphael Lyne (2017)

- W. B. Yeats: The Poems [c. 5 vols], ed. Peter McDonald (2020- )

- Ben Jonson: The Poems, ed. Tom Cain & Ruth Connolly (2021)

- Samuel Johnson: The Complete Poems, ed. Robert D. Brown & Robert DeMaria, Jr. (2024)

- Lord Byron: The Poems [c. 5 vols], ed. Jane Stabler & Gavin Hopps (2024- )

- Thucydides: The Landmark Peloponnesian War, ed. Robert B. Strassler (1996)

- Herodotus: The Landmark Histories, ed. Robert B. Strassler (2007)

- Xenophon: The Landmark Hellenika, ed. Robert B. Strassler (2009)

- Arrian: The Landmark Campaigns of Alexander, ed. James Romm (2010)

- Julius Caesar: The Landmark Complete Works, ed. Kurt A. Raaflaub (2017)

- Xenophon: The Landmark Anabasis, ed. Shane Brennan & David Thomas (2021)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, ed. Martin Gardner (1999)

- L. Frank Baum: The Annotated Wizard of Oz, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (2000)

- Mark Twain: The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (2001)

- Anon.: The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar (2002)

- Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The Annotated Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar (2004)

- Charles Dickens: The Annotated Christmas Carol, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (2004)

- The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. Leslie S. Klinger, 3 vols (2005-6)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes & The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (2005)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow & The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (2005)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear (2006)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Hunting of the Snark, ed. Martin Gardner (2006)

- Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Hollis Robbins (2007)

- Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Annotated Secret Garden, ed. Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (2007)

- Hans Christian Andersen: The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, ed. Maria Tatar & Julie K. Allen (2007)

- Bram Stoker: The New Annotated Dracula, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2008)

- Kenneth Grahame: The Annotated Wind in the Willows, ed. Annie Gauger (2009)

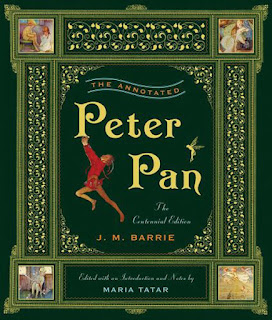

- J. M. Barrie: The Annotated Peter Pan, ed. Maria Tatar (2011)

- H. P. Lovecraft: The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2014)

- Louisa May Alcott: The Annotated Little Women, ed. John Matteson (2015)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition, ed. Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein (2015)

- Mary Shelley: The New Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2017)

- Anon.: The Annotated African American Folktales, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Maria Tatar (2018)

- Ulysses S. Grant: The Annotated Memoirs. ed. Elizabeth D. Samet (2019)

- H. P. Lovecraft: The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft: Beyond Arkham, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2019)

- Virginia Woolf: The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, ed. Merve Emre (2021)

- Anon.: The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights, ed. Paulo Lemos Horta (2021)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Pride and Prejudice, ed. David M. Shapard (2004)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Persuasion, ed. David M. Shapard (2010)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Sense and Sensibility, ed. David M. hapard (2011)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Emma, ed. David M. Shapard (2012)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Northanger Abbey, ed. David M. Shapard (2013)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Mansfield Park, ed. David M. Shapard (2017)

- John Donne: The Songs and Sonets, ed. Theodore Redpath (2009)

- Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows, ed. Seth Lerer (2009)

- Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice, ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks (2010)

- Jane Austen: Persuasion, ed. Robert Morrison (2011)

- Charles Darwin: The Annotated Origin, ed. James T. Costa (2011)

- Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2011)

- Jane Austen: Emma, ed. Bharat Tandon (2012)

- Thomas Jefferson, James Madison et al: The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence, ed. Jack N. Rakove (2012)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Annotated Emerson, ed. David Mikics (2012)

- Mary Shelley: The Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Susan J. Wolfson & Ronald Levao (2012)

- Louisa May Alcott: Little Women, ed. Daniel Shealy (2013)

- Jane Austen: Sense and Sensibility, ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks (2013)

- Alfred Russell Wallace: On the Organic Law of Change, ed. James T. Costa (2013)

- Jane Austen: Northanger Abbey, ed. Susan J. Wolfson (2014)

- Emily Brontë: The Annotated Wuthering Heights, ed. Janet Gezari (2014)

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Annotated Poe, ed. Kevin J. Hayes (2015)

- Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Importance of Being Earnest, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2015)

- Jane Austen: Mansfield Park, ed. Deidre Shauna Lynch (2016)

- Abraham Lincoln: The Annotated Lincoln, ed. Harold Holzer & Thomas A. Horrocks (2016)

- Ulysses S. Grant: The Personal Memoirs, ed. John F. Marszalek (2017)

- Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Prison Writings, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2018)

- Oscar Wilde: The Short Stories: An Annotated Selection, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2020)

- Oscar Wilde: The Critical Writings: An Annotated Selection, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2022)

- Vladimir Nabokov: The Annotated Lolita, ed. Alfred J. Appel, Jr. (1970 / 1991)

- Lord Byron: Asimov's Annotated Don Juan, ed. Isaac Asimov (1972)

- Edward Thomas: Poems and Last Poems, ed. Edna Longley (1973)

- John Milton: Asimov's Annotated Paradise Lost, ed. Isaac Asimov (1974)

- Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. Ed. Walter James Miller (1976)

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Short Fiction: An Annotated Edition, ed. Stuart & Susan Levine (1977)

- Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon. Ed. & trans. Walter James Miller (1978)

- Charles Darwin: The Illustrated Origin of Species, ed. Richard Leakey (1979)

- Bram Stoker. The Essential Dracula: A Completely Illustrated & Annotated Edition. Ed. Raymond McNally & Radu Florescu (1979)

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Annotated Tales, ed. Stephen Peithman (1981)

- W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: The Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, ed. Ian Bradley (1982 / 2001)

- Jerome K. Jerome: Three Men in a Boat: Annotated Edition. Ed. Christopher Matthew & Benny Green (1982)

- G. K. Chesterton: The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown, ed. Martin Gardner (1987)

- W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: Asimov's Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, ed. Isaac Asimov (1988)

- Lytton Strachey: Eminent Victorians: The Illustrated Edition, ed. Frances Partridge (1988)

- Lytton Strachey: The Illustrated Queen Victoria, ed. Michael Holroyd (1988)

- J. R. R. Tolkien. The Annotated Hobbit: The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, ed. Douglas A. Anderson (1988)

- Lewis Carroll: More Annotated Alice, ed. Martin Gardner (1990)

- Joseph Furphy: The Annotated Such is Life, ed. Frances Devlin Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, & G. W. Turner (1991)

- Clement Moore: The Annotated Night Before Christmas, ed. Martin Gardner (1991)

- Bram Stoker. The Essential Dracula: Including the Complete Novel. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Rev. with Roxana Stuart. Illustrations by Christopher Bing (1993)

- E. B. White. The Annotated Charlotte’s Web. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Ed. Peter F. Neumeyer (1994)

- Robert Louis Stevenson. The Essential Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Illustrations by Michael Lark (1995 / 2005)

- L. M. Montgomery: The Annotated Anne of Green Gables, ed. Margaret Anne Doody, Mary Doody Jones, & Wendy Barry (1997)

- H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. S. T. Joshi. Illustrations by Michael Lark (1997)

- H. P. Lovecraft. More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. S. T. Joshi & Peter Cannon (1998)

- G. K. Chesterton: The Annotated Thursday, ed. Martin Gardner (1999)

- William Empson: The Complete Poems, ed. John Haffenden (2000)

- H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature. Ed. S. T. Joshi (2000)

- J. R. R. Tolkien. The Annotated Hobbit: Revised and Expanded Edition. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson (2002)

- Charles Darwin: On the Origin of Species: The Illustrated Edition, ed. David Quammen (2008)

- Edgar Allan Poe: Annotated Short Stories, ed. Andrew Barger (2008)

- Edgar Allan Poe: Annotated Poems, ed. Andrew Barger (2008)

- Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems, ed. Edna Longley (2008)

- Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams: Illustrated Edition, ed. Jeffrey M. Masson (2010)

- Norton Juster. The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth. Illustrated by Jules Feiffer. Ed. Leonard S. Marcus (2011)

- Neil Gaiman. The Annotated Sandman. 4 vols. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2012-15)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, ed. Pamela Smith Hill (2014)

- Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons. Watchmen: The Annotated Edition. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2017)

- Leslie S. Klinger, ed. Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Introduction by Otto Penzler (2018)

- Neil Gaiman. The Annotated American Gods. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2019)

- Robert Louis Stevenson. The New Annotated Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2022)

- F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Annotated Great Gatsby, ed. James L. W. West III (2025)

-

1960s:

- [1960] - Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1962] - Anon.: The Annotated Mother Goose, ed. William S. Baring-Gould & Ceil Baring-Gould

- [1962] - Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Snark, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1964] - Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern

- [1965] - Matthew Arnold: The Poems, ed. Kenneth Allott

- [1965] - Samuel Taylor Coleridge: The Annotated Ancient Mariner, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1967] - Ernest Lawrence Thayer: The Annotated Casey at the Bat, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1967] - Arthur Conan Doyle: The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. William S. Baring-Gould (2 vols)

- The Early Holmes (c. 1874-1887)

- An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes (c.1889-1914)

- [1968] - John Milton: Paradise Lost, ed. Alastair Fowler

- [1969] - John Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. John Carey

- [1969] - Thomas Gray, William Collins & Oliver Goldsmith: The Poems, ed. Roger Lonsdale

- [1969] - Alfred Tennyson: The Poems, ed. Christopher Ricks

- [1970] - John Keats: The Poems, ed. Miriam Allott

- [1970] - Vladimir Nabokov: The Annotated Lolita, ed. Alfred J. Appel, Jr.

- [1970] - Henry D. Thoreau: The Annotated Walden, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern

- [1972] - William Blake: The Poems, ed. W. H. Stevenson & David V. Erdman

- [1972] - Lord Byron: Asimov's Annotated Don Juan, ed. Isaac Asimov

- [1973] - L. Frank Baum: The Annotated Wizard of Oz, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1973)

- [1973] - Edward Thomas: Poems and Last Poems, ed. Edna Longley

- [1974] - John Milton: Asimov's Annotated Paradise Lost, ed. Isaac Asimov

- [1975] - Bram Stoker: The Annotated Dracula, ed. Leonard Wolf (1975)

- [1976] - Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. Ed. Walter James Miller

- [1977] - Charles Dickens: The Annotated Christmas Carol, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn

- [1977] - Edgar Allan Poe: The Short Fiction: An Annotated Edition, ed. Stuart & Susan Levine

- [1977] - Mary Shelley: The Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Leonard Wolf

- [1977] - Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene, ed. A. C. Hamilton

- [1978] - William Shakespeare: The Annotated Shakespeare, ed. A. L. Rowse (3 vols)

- Comedies

- Histories and Poems

- Tragedies and Romances

- [1978] - Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon. Ed. & trans. Walter James Miller

- [1979] - Charles Darwin: The Illustrated Origin of Species, ed. Richard Leakey

- [1979] - Bram Stoker. The Essential Dracula: A Completely Illustrated & Annotated Edition. Ed. Raymond McNally & Radu Florescu

- [1980] - Jonathan Swift: The Annotated Gulliver’s Travels, ed. Isaac Asimov

- [1981] - Edgar Allan Poe: The Annotated Tales, ed. Stephen Peithman

- [1981] - Mark Twain: The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn

- [1982] - W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: The Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, ed. Ian Bradley

- [1982] - Jerome K. Jerome: Three Men in a Boat: Annotated Edition. Ed. Christopher Matthew & Benny Green

- [1982] - Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Oscar Wilde, ed. H. Montgomery Hyde

- [1987] - G. K. Chesterton: The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1986] - Charles Dickens: The Annotated Dickens, ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins (2 vols)

- The Pickwick Papers / Oliver Twist / A Christmas Carol / Hard Times

- David Copperfield / A Tale of Two Cities / Great Expectations

- [1987] - Alfred Tennyson: The Poems: Revised Edition, 3 vols, ed. Christopher Ricks

- [1988] - W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: Asimov's Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, ed. Isaac Asimov

- [1988] - Lytton Strachey: Eminent Victorians: The Illustrated Edition, ed. Frances Partridge

- [1988] - Lytton Strachey: The Illustrated Queen Victoria, ed. Michael Holroyd

- [1988] - J. R. R. Tolkien. The Annotated Hobbit: The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson

- [1989-2024] - Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Poems [6 vols], ed. Kelvin Everest & Geoffrey Matthews

- [1990] - Lewis Carroll: More Annotated Alice, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1991] - Joseph Furphy: The Annotated Such is Life, ed. Frances Devlin Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, & G. W. Turner

- [1991] - Clement Moore: The Annotated Night Before Christmas, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1991- ] - Robert Browning: The Poems [c. 7 vols], ed. John Woolford, Daniel Karlin & Joseph Phelan

- [1993] - Bram Stoker. The Essential Dracula: Including the Complete Novel. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Rev. with Roxana Stuart. Illustrations by Christopher Bing

- [1994] - E. B. White. The Annotated Charlotte’s Web. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Ed. Peter F. Neumeyer

- [1995] - Robert Louis Stevenson. The Essential Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Illustrations by Michael Lark

- [1995-2007] - John Dryden: The Poems [5 vols], ed. Paul Hammond & David Hopkins

- [1996] - Thucydides: The Landmark Peloponnesian War, ed. Robert B. Strassler

- [1997] - H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. S. T. Joshi. Illustrations by Michael Lark

- [1997] - L. M. Montgomery: The Annotated Anne of Green Gables, ed. Margaret Anne Doody, Mary Doody Jones, & Wendy Barry

- [1998] - H. P. Lovecraft. More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. S. T. Joshi & Peter Cannon

- [1999] - Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, ed. Martin Gardner

- [1999] - G. K. Chesterton: The Annotated Thursday, ed. Martin Gardner

- [2000] - L. Frank Baum: The Annotated Wizard of Oz, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn

- [2000] - William Empson: The Complete Poems, ed. John Haffenden

- [2000] - H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature. Ed. S. T. Joshi

- [2001] - Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene: Revised Edition, ed. Hiroshi Yamashita & Toshiyuki Suzuki

- [2001] - Mark Twain: The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn

- [2002] - Anon.: The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar (2002)

- [2002] - J. R. R. Tolkien. The Annotated Hobbit: Revised and Expanded Edition. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson

- [2003] - Andrew Marvell: The Poems, ed. Nigel Smith

- [2004] - Jane Austen: The Annotated Pride and Prejudice, ed. David M. Shapard

- [2004] - Charles Dickens: The Annotated Christmas Carol, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn

- [2004] - Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The Annotated Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar

- [2005-6] - Arthur Conan Doyle: The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (3 vols)

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes & The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (2005)

- The Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow & The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (2005)

- A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear (2006)

- [2006] - Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Hunting of the Snark, ed. Martin Gardner

- [2007] - Hans Christian Andersen: The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, ed. Maria Tatar & Julie K. Allen

- [2007] - Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Annotated Secret Garden, ed. Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina

- [2007] - Herodotus: The Landmark Histories, ed. Robert B. Strassler (2007)

- [2007] - Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Hollis Robbins

- [2007- ] - Alexander Pope: The Poems [c. 6 vols], ed. Julian Ferraro & Paul Baines

- [2008] - Charles Darwin: On the Origin of Species: The Illustrated Edition, ed. David Quammen

- [2008] - Edgar Allan Poe: Annotated Short Stories, ed. Andrew Barger

- [2008] - Edgar Allan Poe: Annotated Poems, ed. Andrew Barger

- [2008] - Bram Stoker: The New Annotated Dracula, ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2008] - Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems, ed. Edna Longley

- [2009] - John Donne: The Songs and Sonets, ed. Theodore Redpath

- [2009] - Kenneth Grahame: The Annotated Wind in the Willows, ed. Annie Gauger

- [2009] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows, ed. Seth Lerer

- [2009] - Xenophon: The Landmark Hellenika, ed. Robert B. Strassler

- [2010] - Arrian: The Landmark Campaigns of Alexander, ed. James Romm

- [2010] - Jane Austen: The Annotated Persuasion, ed. David M. Shapard

- [2010] - Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice, ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks

- [2010] - John Donne: The Complete Poems, ed. Robin Robbins

- [2010] - Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams: Illustrated Edition, ed. Jeffrey M. Masson

- [2011] - Jane Austen: Persuasion, ed. Robert Morrison

- [2011] - Jane Austen: The Annotated Sense and Sensibility, ed. David M. Shapard

- [2011] - J. M. Barrie: The Annotated Peter Pan, ed. Maria Tatar

- [2011] - Charles Darwin: The Annotated Origin, ed. James T. Costa

- [2011] - Norton Juster. The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth. Illustrated by Jules Feiffer. Ed. Leonard S. Marcus

- [2011] - Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray, ed. Nicholas Frankel

- [2012] - Jane Austen: The Annotated Emma, ed. David M. Shapard

- [2012] - Jane Austen: Emma, ed. Bharat Tandon

- [2012] - Thomas Jefferson, James Madison et al: The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence, ed. Jack N. Rakove

- [2012] - Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Annotated Emerson, ed. David Mikics

- [2012] - Mary Shelley: The Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Susan J. Wolfson & Ronald Levao

- [2012-15] - Neil Gaiman. The Annotated Sandman. 4 vols. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2013] - Louisa May Alcott: Little Women, ed. Daniel Shealy

- [2013] - Jane Austen: The Annotated Northanger Abbey, ed. David M. Shapard

- [2013] - Jane Austen: Sense and Sensibility, ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks

- [2013] - Alfred Russell Wallace: On the Organic Law of Change, ed. James T. Costa

- [2014] - Jane Austen: Northanger Abbey, ed. Susan J. Wolfson

- [2014] - Emily Brontë: The Annotated Wuthering Heights, ed. Janet Gezari

- [2014] - H. P. Lovecraft: The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft, ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2014] - Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, ed. Pamela Smith Hill

- [2015] - Louisa May Alcott: The Annotated Little Women, ed. John Matteson

- [2015] - Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition, ed. Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein

- [2015] - Edgar Allan Poe: The Annotated Poe, ed. Kevin J. Hayes

- [2015] - Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Importance of Being Earnest, ed. Nicholas Frankel

- [2016] - Jane Austen: Mansfield Park, ed. Deidre Shauna Lynch

- [2016] - Abraham Lincoln: The Annotated Lincoln, ed. Harold Holzer & Thomas A. Horrocks

- [2017] - Jane Austen: The Annotated Mansfield Park, ed. David M. Shapard

- [2017] - Julius Caesar: Complete Works, ed. Kurt A. Raaflaub

- [2017] - Ulysses S. Grant: The Personal Memoirs, ed. John F. Marszalek

- [2017] - Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons. Watchmen: The Annotated Edition. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2017] - William Shakespeare: The Complete Poems, ed. Cathy Shrank & Raphael Lyne

- [2017] - Mary Shelley: The New Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2018] - Anon.: The Annotated African American Folktales, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Maria Tatar

- [2018] - Leslie S. Klinger, ed. Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Introduction by Otto Penzler

- [2018] - Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Prison Writings, ed. Nicholas Frankel

- [2019] - Neil Gaiman. The Annotated American Gods. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2019] - Ulysses S. Grant: The Annotated Memoirs. ed. Elizabeth D. Samet

- [2019] - H. P. Lovecraft: The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft: Beyond Arkham, ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2020] - Oscar Wilde: The Short Stories: An Annotated Selection, ed. Nicholas Frankel

- [2020- ] - W. B. Yeats: The Poems [c. 5 vols], ed. Peter McDonald

- [2021] - Anon.: The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights, ed. Paulo Lemos Horta

- [2021] - Ben Jonson: The Poems, ed. Tom Cain & Ruth Connolly

- [2021] - Virginia Woolf: The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, ed. Merve Emre

- [2021] - Xenophon: The Landmark Anabasis, ed. Shane Brennan & David Thomas

- [2022] - Robert Louis Stevenson. The New Annotated Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger

- [2022] - Oscar Wilde: The Critical Writings: An Annotated Selection, ed. Nicholas Frankel

- [2024] - Samuel Johnson: The Complete Poems, ed. Robert D. Brown & Robert DeMaria, Jr.

- [2024- ] - Lord Byron: The Poems [c. 5 vols], ed. Jane Stabler & Gavin Hopps

- [2025] - F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Annotated Great Gatsby, ed. James L. W. West III

•

1970s:

•

1980s:

•

1990s:

•

2000s:

•

2010s:

•

2020s:

- Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888):

- Louisa May Alcott: Little Women, ed. Daniel Shealy (2013)

- Louisa May Alcott: The Annotated Little Women, ed. John Matteson (2015)

- Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875):

- Hans Christian Andersen: The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, ed. Maria Tatar & Julie K. Allen (2007)

- Anonymous:

- Anon.: The Annotated Mother Goose, ed. William S. Baring-Gould & Ceil Baring-Gould (1962)

- Anon.: The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar (2002)

- Anon.: The Annotated African American Folktales, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Maria Tatar (2018)

- Anon.: The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights, ed. Paulo Lemos Horta (2021)

- Matthew Arnold (1822-1888):

- Matthew Arnold: The Poems, ed. Kenneth Allott (1965)

- Arrian of Nicomedia (c.86/8 –c.146/160 CE):

- Arrian: The Landmark Campaigns of Alexander, ed. James Romm (2010)

- Jane Austen (1775-1817):

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Pride and Prejudice, ed. David M. Shapard (2004)

- Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice, ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks (2010)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Persuasion, ed. David M. Shapard (2010)

- Jane Austen: Persuasion, ed. Robert Morrison (2011)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Sense and Sensibility, ed. David M. Shapard (2011)

- Jane Austen: Sense and Sensibility, ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks (2013)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Emma, ed. David M. Shapard (2012)

- Jane Austen: Emma, ed. Bharat Tandon (2012)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Northanger Abbey, ed. David M. Shapard (2013)

- Jane Austen: Northanger Abbey, ed. Susan J. Wolfson (2014)

- Jane Austen: Mansfield Park, ed. Deidre Shauna Lynch (2016)

- Jane Austen: The Annotated Mansfield Park, ed. David M. Shapard (2017)

- Sir James Matthew Barrie (1860-1937):

- J. M. Barrie: The Annotated Peter Pan, ed. Maria Tatar (2011)

- Lyman Frank Baum (1856-1919):

- L. Frank Baum: The Annotated Wizard of Oz, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1973)

- L. Frank Baum: The Annotated Wizard of Oz, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (2000)

- Earl Derr Biggers (1884–1933):

- Earl Derr Biggers, S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Dashiell Hammett & W. R. Burnett: Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2018)

- William Blake (1757-1827):

- William Blake: The Poems, ed. W. H. Stevenson & David V. Erdman (1972)

- Emily Jane Brontë (1818-1848):

- Emily Brontë: The Annotated Wuthering Heights, ed. Janet Gezari (2014)

- Robert Browning (1812-1889):

- Robert Browning: The Poems [c. 7 vols], ed. John Woolford, Daniel Karlin & Joseph Phelan (1991- / 2010)

- Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849-1924):

- Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Annotated Secret Garden, ed. Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (2007)

- William Riley Burnett (1899–1982):

- Earl Derr Biggers, S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Dashiell Hammett & W. R. Burnett: Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2018)

- George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (1788–1824):

- Lord Byron: Asimov's Annotated Don Juan, ed. Isaac Asimov (1972)

- Lord Byron: The Poems [c. 5 vols], ed. Jane Stabler & Gavin Hopps (2024-?)

- Gaius Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE):

- Julius Caesar: The Landmark Complete Works, ed. Kurt A. Raaflaub (2017)

- Lewis Carroll (1832-1898):

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice, ed. Martin Gardner (1960)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Snark, ed. Martin Gardner (1962)

- Lewis Carroll: More Annotated Alice, ed. Martin Gardner (1990)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, ed. Martin Gardner (1999)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Hunting of the Snark, ed. Martin Gardner (2006)

- Lewis Carroll: The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition, ed. Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein (2015)

- Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936):

- G. K. Chesterton: The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown, ed. Martin Gardner (1987)

- G. K. Chesterton: The Annotated Thursday, ed. Martin Gardner (1999)

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834):

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge: The Annotated Ancient Mariner, ed. Martin Gardner (1965)

- William Collins (1721-1759):

- Thomas Gray, William Collins & Oliver Goldsmith: The Poems, ed. Roger Lonsdale (1969)

- Charles Robert Darwin (1809–1882):

- Charles Darwin: The Illustrated Origin of Species, ed. Richard Leakey (1979)

- Charles Darwin: On the Origin of Species: The Illustrated Edition, ed. David Quammen (2008)

- Charles Darwin: The Annotated Origin, ed. James T. Costa (2011)

- Charles John Huffam Dickens (1812-1870):

- Charles Dickens: The Annotated Christmas Carol, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1977)

- Charles Dickens: The Annotated Dickens, ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins, 2 vols (1986)

- The Pickwick Papers / Oliver Twist / A Christmas Carol / Hard Times

- David Copperfield / A Tale of Two Cities / Great Expectations

- Charles Dickens: The Annotated Christmas Carol, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (2004)

- John Donne (1572-1631):

- John Donne: The Complete Poems, ed. Robin Robbins (2010)

- John Donne: The Songs and Sonets, ed. Theodore Redpath (2009)

- Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (1859–1930):

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. William S. Baring-Gould, 2 vols (1967)

- The Early Holmes (c. 1874-1887)

- An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes (c.1889-1914)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. Leslie S. Klinger, 3 vols (2005-6)

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes & The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (2005)

- The Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow & The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (2005)

- A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear (2006)

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. William S. Baring-Gould, 2 vols (1967)

- John Dryden (1631-1700):

- John Dryden: The Poems [5 vols], ed. Paul Hammond & David Hopkins (1995-2005)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882):

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Annotated Emerson, ed. David Mikics (2012)

- Sir William Empson (1906-1984):

- William Empson: The Complete Poems, ed. John Haffenden (2000)

- Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (1896-1940):

- F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Annotated Great Gatsby, ed. James L. W. West III (2025)

- Sigismund Schlomo [Sigmund] Freud (1856-1939):

- Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams: Illustrated Edition, ed. Jeffrey M. Masson (2010)

- Joseph Furphy [Seosamh Ó Foirbhithe]; pen name 'Tom Collins' (1843-1912):

- Joseph Furphy: The Annotated Such is Life, ed. Frances Devlin Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, & G. W. Turner (1991)

- Neil Richard MacKinnon Gaiman (1960- )

- Neil Gaiman: The Annotated Sandman. 4 vols. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2012-15)

- Neil Gaiman: The Annotated American Gods. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2019)

- David Chester Gibbons (1949- ):

- Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons: Watchmen: The Annotated Edition. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2017)

- Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (1836-1911):

- W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: The Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, ed. Ian Bradley (1982 / 2001)

- W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: Asimov's Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, ed. Isaac Asimov (1988)

- Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774):

- Thomas Gray, William Collins & Oliver Goldsmith: The Poems, ed. Roger Lonsdale (1969)

- Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932):

- Kenneth Grahame: The Annotated Wind in the Willows, ed. Annie Gauger (2009)

- Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows, ed. Seth Lerer (2009)

- Ulysses S. Grant [born Hiram Ulysses Grant] (1822–1885):

- Ulysses S. Grant: The Personal Memoirs, ed. John F. Marszalek (2017)

- Ulysses S. Grant: The Annotated Memoirs. ed. Elizabeth D. Samet (2019)

- Thomas Gray (1716-1771):

- Thomas Gray, William Collins & Oliver Goldsmith: The Poems, ed. Roger Lonsdale (1969)

- Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (1785-1863):

- Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The Annotated Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar (2004)

- Wilhelm Carl Grimm (1786-1859):

- Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The Annotated Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales, ed. Maria Tatar (2004)

- Samuel Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961):

- Earl Derr Biggers, S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Dashiell Hammett & W. R. Burnett: Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2018)

- Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c.484–c.425 BCE)

- Herodotus: The Landmark Histories, ed. Robert B. Strassler (2007)

- Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826):

- Thomas Jefferson, James Madison et al: The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence, ed. Jack N. Rakove (2012)

- Jerome Klapka Jerome (1859-1927):

- Jerome K. Jerome: Three Men in a Boat: Annotated Edition. Ed. Christopher Matthew & Benny Green (1982)

- Samuel Johnson (1709-1784):

- Samuel Johnson: The Complete Poems, ed. Robert D. Brown & Robert DeMaria, Jr. (2024)

- Benjamin Jonson (1572-1637):

- Ben Jonson: The Poems, ed. Tom Cain & Ruth Connolly (2021)

- Norton Juster (1929-2021):

- Norton Juster: The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth. Illustrated by Jules Feiffer. Ed. Leonard S. Marcus (2011)

- John Keats (1795-1821):

- John Keats: The Poems, ed. Miriam Allott (1970)

- Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865):

- Abraham Lincoln: The Annotated Lincoln, ed. Harold Holzer & Thomas A. Horrocks (2016)

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890-1937):

- H. P. Lovecraft: The Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. S. T. Joshi. Illustrations by Michael Lark (1997)

- H. P. Lovecraft. More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. S. T. Joshi & Peter Cannon (1998)

- H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature. Ed. S. T. Joshi (2000)

- H. P. Lovecraft: The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2014)

- H. P. Lovecraft: The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft: Beyond Arkham, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2019)

- James Madison (1750-1836):

- Thomas Jefferson, James Madison et al: The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence, ed. Jack N. Rakove (2012)

- Andrew Marvell (1621-1678):

- Andrew Marvell: The Poems, ed. Nigel Smith (2003)

- John Milton (1608-1674):

- John Milton: Paradise Lost, ed. Alastair Fowler (1968)

- John Milton: The Complete Shorter Poems, ed. John Carey (1968)

- John Milton: Asimov's Annotated Paradise Lost, ed. Isaac Asimov (1974)

- Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874-1942):

- L. M. Montgomery: The Annotated Anne of Green Gables, ed. Margaret Anne Doody, Mary Doody Jones, & Wendy Barry (1997)

- Alan Moore (1953- ):

- Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons: Watchmen: The Annotated Edition. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2017)

- Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863):

- Clement Moore: The Annotated Night Before Christmas, ed. Martin Gardner (1991)

- Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (1899-1977):

- Vladimir Nabokov: The Annotated Lolita, ed. Alfred J. Appel, Jr. (1970)

- Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849):

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Short Fiction: An Annotated Edition, ed. Stuart & Susan Levine (1977)

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Annotated Tales, ed. Stephen Peithman (1981)

- Edgar Allan Poe: Annotated Short Stories, ed. Andrew Barger (2008)

- Edgar Allan Poe: Annotated Poems, ed. Andrew Barger (2008)

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Annotated Poe, ed. Kevin J. Hayes (2015)

- Alexander Pope (1688-1744):

- Alexander Pope: The Poems [c. 6 vols], ed. Julian Ferraro & Paul Baines (2007- )

- Ellery Queen [pseudonym of Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred Bennington Lee (1905–1971)]:

- Earl Derr Biggers, S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Dashiell Hammett & W. R. Burnett: Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2018)

- William Shakespeare (1564-1616):

- The Annotated Shakespeare, ed. A. L. Rowse, 3 vols (1978)

- William Shakespeare: Comedies

- William Shakespeare: Histories and Poems

- William Shakespeare: Tragedies and Romances

- William Shakespeare: The Complete Poems, ed. Cathy Shrank & Raphael Lyne (2017)

- The Annotated Shakespeare, ed. A. L. Rowse, 3 vols (1978)

- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797-1851):

- Mary Shelley: The Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Leonard Wolf (1977)

- Mary Shelley: The Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Susan J. Wolfson & Ronald Levao (2012)

- Mary Shelley: The New Annotated Frankenstein, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2017)

- Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822):

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Poems [6 vols], ed. Kelvin Everest & Geoffrey Matthews (1989-2024)

- Edmund Spenser (1552-1599):

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene, ed. A. C. Hamilton (1977)

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene: Revised Edition, ed. Hiroshi Yamashita & Toshiyuki Suzuki (2001)

- Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894):

- Robert Louis Stevenson. The Essential Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Illustrations by Michael Lark (1995 / 2005)

- Robert Louis Stevenson. The New Annotated Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2022)

- Abraham [Bram] Stoker (1847-1912):

- Bram Stoker: The Annotated Dracula, ed. Leonard Wolf (1975)

- Bram Stoker: The Essential Dracula: A Completely Illustrated & Annotated Edition. Ed. Raymond McNally & Radu Florescu (1979)

- Bram Stoker: The Essential Dracula: Including the Complete Novel. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Rev. with Roxana Stuart. Illustrations by Christopher Bing (1993)

- Bram Stoker: The New Annotated Dracula, ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2008)

- Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (1811-1896):

- Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern (1964)

- Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Hollis Robbins (2007)

- Giles Lytton Strachey (1880-1932):

- Lytton Strachey: Eminent Victorians: The Illustrated Edition, ed. Frances Partridge (1988)

- Lytton Strachey: The Illustrated Queen Victoria, ed. Michael Holroyd (1988)

- Jonathan Swift (1667-1745):

- Jonathan Swift: The Annotated Gulliver’s Travels, ed. Isaac Asimov (1980)

- Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (1809-1892):

- Alfred Tennyson: The Poems, ed. Christopher Ricks (1969)

- Alfred Tennyson: The Poems: Revised Edition, 3 vols, ed. Christopher Ricks (1987)

- Ernest Lawrence Thayer (1863-1940):

- Ernest Lawrence Thayer: The Annotated Casey at the Bat, ed. Martin Gardner (1967)

- Philip Edward Thomas (1878-1917):

- Edward Thomas: Poems and Last Poems, ed. Edna Longley (1973)

- Edward Thomas: The Annotated Collected Poems, ed. Edna Longley (2008)

- David Henry [Henry David] Thoreau (1817-1862):

- Henry D. Thoreau: The Annotated Walden, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern (1970)

- Thucydides (c.460–c.400 BCE)

- Thucydides: The Landmark Peloponnesian War, ed. Robert B. Strassler (1996)

- John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892-1973):

- J. R. R. Tolkien: The Annotated Hobbit: The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson (1988)

- J. R. R. Tolkien: The Annotated Hobbit: Revised and Expanded Edition. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson (2002)

- Samuel Langhorne Clemens [Mark Twain] (1835-1910):

- Mark Twain: The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (1981)

- Mark Twain: The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (2001)

- Willard Huntingdon Wright [S. S. Van Dine] (1888-1939)

- Earl Derr Biggers, S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Dashiell Hammett & W. R. Burnett: Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2018)

- Jules Gabriel Verne (1828-1905):

- Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. Ed. Walter James Miller (1976)

- Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon. Ed. & trans. Walter James Miller (1978)

- Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913):

- Alfred Russell Wallace: On the Organic Law of Change, ed. James T. Costa (2013)

- Elwyn Brooks White (1899-1985):

- E. B. White: The Annotated Charlotte’s Web. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Ed. Peter F. Neumeyer (1994)

- Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (1854-1900):

- Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Oscar Wilde, ed. H. Montgomery Hyde (1982)

- Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2011)

- Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Importance of Being Earnest, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2015)

- Oscar Wilde: The Annotated Prison Writings, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2018)

- Oscar Wilde: The Short Stories: An Annotated Selection, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2020)

- Oscar Wilde: The Critical Writings: An Annotated Selection, ed. Nicholas Frankel (2022)

- Laura Ingalls Wilder (1867-1957):

- Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, ed. Pamela Smith Hill (2014)

- Adeline Virginia Woolf (née Stephen) (1882-1941):

- Virginia Woolf: The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, ed. Merve Emre (2021)

- Xenophon of Athens (c.430–355/354 BCE):

- Xenophon: The Landmark Hellenika, ed. Robert B. Strassler (2009)

- Xenophon: The Landmark Anabasis, ed. Shane Brennan & David Thomas (2021)

- William Butler Yeats (1865-1939):

- W. B. Yeats: The Poems [c. 5 vols], ed. Peter McDonald (2020- )

- Julie K. Allen

- Hans Christian Andersen. The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen. Ed. Maria Tatar. Trans. Maria Tatar & Julie K. Allen. Introduction by A. S. Byatt. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2007.

- Kenneth Allott (1912-1973)

- Matthew Arnold. The Poems. Longmans Annotated English Poets. Ed. Kenneth Allott. London: Longmans, Green & Co. Ltd., 1965.

- Miriam Allott (1920-2010)

- John Keats. The Poems. Longmans Annotated English Poets. Ed. Miriam Allott. London: Longman, 1970.

- Douglas A. Anderson (1959- )

- J. R. R. Tolkien. The Annotated Hobbit: The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. 1937. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson. London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

- J. R. R. Tolkien. The Annotated Hobbit: Revised and Expanded Edition. 1937. Ed. Douglas A. Anderson. 1988. Rev. ed. 2002. London: HarperCollins, 2003)

- Alfred J. Appel, Jr. (1934-2009)

- Vladimir Nabokov. The Annotated Lolita. 1955. Ed. Alfred Appel, Jr. 1970. Rev. ed. 1991. Vintage Books. New York: Random House, Inc., 1991.

- Isaac Asimov (1920-1992)

- Lord Byron. Asimov's Annotated Don Juan: An Original Interpretation of Lord Byron's Epic Poem. Ed. Isaac Asimov. Illustrated by Milton Glaser. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1972)

- John Milton. Asimov's Annotated Paradise Lost: An Original Interpretation of Milton's Epic Poem. Ed. Isaac Asimov. New York: Doubleday, 1974.

- Jonathan Swift. The Annotated Gulliver’s Travels: Gulliver's Travels, by Jonathan Swift. 1726 / 1734 / 1896. Ed. Isaac Asimov. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. / Publishers, 1980.

- W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan. Asimov's Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan: An Original Interpretation of the World's Best Loved Light Opera. Ed. Isaac Asimov. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

- Professor Paul Baines

- Alexander Pope. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Julian Ferraro & Paul Baines. Vol. 1 of 6. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Andrew Barger

- Edgar Allan Poe. Annotated Short Stories. Ed. Andrew Barger. USA: Bottletree Books, 2008.

- Edgar Allan Poe. Annotated Poems. Ed. Andrew Barger. USA: Bottletree Books, 2008.

- Lucile Marguerite Moody ['Ceil'] Baring-Gould (1914-2010)

- Anon. The Annotated Mother Goose: Nursery Rhymes Old and New, Arranged and Explained. Ed. William S. Baring-Gould & Ceil Baring-Gould. Illustrated by Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, Arthur Rackham, Maxfield Parrish, and Early Historical Woodcuts. With Chapter Decorations by E. M. Simon. New York: Bramhall House, 1962.

- William S. Baring-Gould (1913-1967)

- Anon. The Annotated Mother Goose: Nursery Rhymes Old and New, Arranged and Explained. Ed. William S. Baring-Gould & Ceil Baring-Gould. Illustrated by Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, Arthur Rackham, Maxfield Parrish, and Early Historical Woodcuts. With Chapter Decorations by E. M. Simon. New York: Bramhall House, 1962.

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The Annotated Sherlock Holmes: The Four Novels and the Fifty-Six Short Stories Complete, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967.

- The Early Holmes (c. 1874-1887)

- An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes (c.1889-1914)

- Wendy Barry

- L. M. Montgomery. The Annotated Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Ed. Margaret Anne Doody, Mary Doody Jones, & Wendy Barry. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- The Reverend Professor Ian Bradley (1950- )

- W. S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. [Trial by Jury (1875); The Sorcerer (1877); H.M.S. Pinafore (1878); The Pirates of Penzance (1879); Patience (1881); Iolanthe (1882); Princess Ida (1884); The Mikado (1885); Ruddigore (1887); The Yeomen of the Guard (1888); The Gondoliers (1889); Utopia Limited (1893); The Grand Duke (1896)]. Ed. Ian Bradley. 1982, 1984, 1996. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Shane Brennan

- Xenophon. The Landmark Anabasis. Trans. David Thomas. Ed. Shane Brennan & David Thomas. Series Editor: Robert Strassler. Pantheon Books. New York: Penguin Random House LLC, 2021.

- Robert D. Brown

- Samuel Johnson. The Complete Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Robert D. Brown & Robert DeMaria, Jr. London: Routledge, 2024.

- Mark Burstein (1950- )

- Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Illustrations by John Tenniel. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein. 1960, 1990 & 1999. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2015.

- Tom Cain

- Ben Jonson. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Tom Cain & Ruth Connolly. London: Routledge, 2021.

- Peter H. Cannon (1951- )

- H. P. Lovecraft. More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. ["The Picture in the House", "The Hound", "The Shunned House", "The Horror at Red Hook", "Cool Air", "The Call of Cthulhu", "Pickman's Model", "The Thing on the Doorstep", "The Haunter of the Dark"]. Ed. S. T. Joshi & Peter Cannon. Introduction by Peter Cannon. New York: Dell, 1998.

- John Carey (1934- )

- John Milton. The Complete Shorter Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. John Carey. 1968. London: Longman Group Limited, 1971.

- Philip Collins (1923-2007)

- Charles Dickens. The Annotated Dickens. Ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986.

- The Pickwick Papers / Oliver Twist / A Christmas Carol / Hard Times

- David Copperfield / A Tale of Two Cities / Great Expectations

- Charles Dickens. The Annotated Dickens. Ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986.

- Ruth Connolly

- Ben Jonson. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Tom Cain & Ruth Connolly. London: Routledge, 2021.

- James T. Costa

- Charles Darwin. The Annotated Origin: A Facsimile of the First Edition of On the Origin of Species. 1859. Ed. James T. Costa. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Alfred Russell Wallace. On the Organic Law of Change: A Facsimile Edition and Annotated Transcription of Alfred Russel Wallace's Species Notebook of 1855-1859. Ed. James T. Costa. Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Robert DeMaria, Jr.

- Samuel Johnson. The Complete Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Robert D. Brown & Robert DeMaria, Jr. London: Routledge, 2024.

- Margaret Anne Doody (1939- )

- L. M. Montgomery. The Annotated Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Ed. Margaret Anne Doody, Mary Doody Jones, & Wendy Barry. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Philippa Robin [P. R. or Robin] Eaden (1943-2001)

- Joseph Furphy: The Annotated Such is Life: Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins. 1903. Ed. Frances Devlin Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, & G. W. Turner. 1991. Rev. ed. Halstead Classics. Rushcutters Bay, NSW: Halstead Press, 1999.

- Merve Emre

- Virginia Woolf. The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway. 1925. Ed. Merve Emre. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021.

- David V. Erdman (1911-2001)

- William Blake. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. W. H. Stevenson. Text by David V. Erdman. 1971. London: Longman / Norton, 1972.

- Kelvin Everest (1950- )

- Percy Bysshe Shelley. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Carlene Adamson, Will Bowers, Jack Donovan, Kelvin Everest, Geoffrey Matthews, Mathelinda Nabugodi, & Michael Rossington. 6 vols. London: Routledge, 1989-2024.

- Julian Ferraro

- Alexander Pope. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Julian Ferraro & Paul Baines. Vol. 1 of 6. London: Routledge, 2019- .

- Radu Florescu (1925-2014)

- Bram Stoker. The Essential Dracula: A Completely Illustrated & Annotated Edition of Bram Stoker’s Classic Novel. 1897. Ed. Raymond McNally & Radu Florescu. New York: Mayflower Books, 1979.

- Alastair Fowler (1930-2022)

- John Milton. Paradise Lost. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Alastair Fowler. 1968. Second Edition. 1997. Pearson Longman. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

- Nicholas Frankel (1962- )

- Oscar Wilde. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. 1890. Ed. Nicholas Frankel. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Oscar Wilde. The Annotated Importance of Being Earnest. 1895. Ed. Nicholas Frankel. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Oscar Wilde. The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde. Ed. Nicholas Frankel. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Oscar Wilde. The Short Stories of Oscar Wilde: An Annotated Selection. Ed. Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Oscar Wilde. The Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde: An Annotated Selection. Ed. Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022.

- Martin Gardner (1914-2020)

- Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass. Illustrated by John Tenniel. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Martin Gardner. Bramhall House. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1960.

- Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Snark: The Hunting of the Snark – An Agony in Eight Fits. Illustrations by Henry Holiday. 1876. Ed. Martin Gardner. 1962. Rev. ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973.

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The Annotated Ancient Mariner: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. 1798. Illustrations by Gustave Doré. 1798. London: Anthony Blond Limited, 1965.

- Ernest Lawrence Thayer. The Annotated Casey at the Bat: A Collection of Ballads about the Mighty Casey. 1888. Ed. Martin Gardner. Bramhall House. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1967.

- G. K. Chesterton. The Annotated Innocence of Father Brown: The Innocence of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton. 1911. Ed. Martin Gardner. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Lewis Carroll: More Annotated Alice: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Martin Gardner. Illustrations by Peter Newell. New York: Random House USA Inc., 1990.

- Clement Moore. The Annotated Night Before Christmas: A Collection of Sequels, Parodies & Imitations of Clement Moore's Immortal Ballad About Santa Claus. 1823. Ed. Martin Gardner. Summit Books. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1991.

- Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Illustrations by John Tenniel. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Martin Gardner. 1960 & 1990. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 1999.

- G. K. Chesterton. The Annotated Thursday: G. K. Chesterton’s Masterpiece The Man Who Was Thursday. 1908. Ed. Martin Gardner. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1999.

- Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Hunting of the Snark: The Definitive Edition. Illustrated by Henry Holiday. 1876. Ed. Martin Gardner. 1962. Introduction by Adam Gopnik. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2006.

- Lewis Carroll. The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. Illustrations by John Tenniel. 1865 & 1871. Ed. Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein. 1960, 1990 & 1999. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2015.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (1950- )

- Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 1852. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Hollis Robbins. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2007.

- Anon. The Annotated African American Folktales. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Maria Tatar. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

- Annie Gauger

- Kenneth Grahame. The Annotated Wind in the Willows. 1908. Ed. Annie Gauger. Introduction by Brian Jacques. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2009.

- Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (1947- )

- Frances Hodgson Burnett. The Annotated Secret Garden. 1911. Ed. Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2007.

- Janet Gezari (1945- )

- Emily Brontë. The Annotated Wuthering Heights. 1847. Ed. Janet Gezari. Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Frances Devlin Glass

- Joseph Furphy: The Annotated Such is Life: Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins. 1903. Ed. Frances Devlin Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, & G. W. Turner. 1991. Rev. ed. Halstead Classics. Rushcutters Bay, NSW: Halstead Press, 1999.

- Benny Green (1927-1998)

- Jerome K. Jerome. Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the Dog): Annotated Edition. 1889. Ed. Christopher Matthew & Benny Green. London: Pavilion Books, Ltd., 1982.

- Edward Guiliano (1950)

- Charles Dickens. The Annotated Dickens, ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins, 2 vols (1986)

- The Pickwick Papers / Oliver Twist / A Christmas Carol / Hard Times

- David Copperfield / A Tale of Two Cities / Great Expectations

- Charles Dickens. The Annotated Dickens, ed. Edward Guiliano & Philip Collins, 2 vols (1986)

- John Haffenden (1945- )

- William Empson. The Complete Poems. Ed. John Haffenden. 2000. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2001.

- Albert Charles Hamilton (1921-2016)

- Edmund Spenser. The Faerie Queene. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. A. C. Hamilton. 1977. London: Longman Group Limited, 1980.

- Paul Hammond

- John Dryden. The Poems of John Dryden. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Paul Hammond & David Hopkins. 5 vols. London: Routledge, 1995-2005.

- Kevin J. Hayes (1959- )

- Edgar Allan Poe. The Annotated Poe. Ed. Kevin J. Hayes. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Michael Patrick Hearn (1950- )

- L. Frank Baum. The Annotated Wizard of Oz: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, by L. Frank Baum. Pictures in Color by W. W. Denslow. 1900. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1973.

- Charles Dickens. The Annotated Christmas Carol: A Christmas Carol in Prose, by Charles Dickens. Illustrations by John Leech. 1843. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1977.

- Mark Twain. The Annotated Huckleberry Finn: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain. Illustrated by E. W. Kemble. 1884. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1981.

- L. Frank Baum. The Annotated Wizard of Oz: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Pictures by W. W. Denslow. 1900. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. 1973. Centennial Edition. Preface by Martin Gardner. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

- Mark Twain (Samuel L. Clemens). The Annotated Huckleberry Finn: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer’s Comrade). Illustrations by E. W. Kemble. 1884. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. 1981. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2001.

- Charles Dickens. The Annotated Christmas Carol: A Christmas Carol in Prose. Illustrations by John Leech. 1843. Ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. 1976. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Pamela Smith Hill (1954- )

- Laura Ingalls Wilder. Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography. Ed. Pamela Smith Hill. A Publication of the Pioneer Girl Project: Nancy Tystad Koupal, Director; Rodger Hartley, Associate Editor; Jeanne Kilen Ode, Associate Editor. Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2014.

- Lois Hoffmann

- Joseph Furphy: The Annotated Such is Life: Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins. 1903. Ed. Frances Devlin Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann, & G. W. Turner. 1991. Rev. ed. Halstead Classics. Rushcutters Bay, NSW: Halstead Press, 1999.

- Michael Holroyd (1935- )

- Lytton Strachey. The Illustrated Queen Victoria. 1921. Introduction by Michael Holroyd. 1987. London: Guild Publishing, 1988.

- Harold Holzer (1949- )

- Abraham Lincoln. The Annotated Lincoln. Ed. Harold Holzer & Thomas A. Horrocks. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- David Hopkins

- John Dryden. The Poems of John Dryden. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Paul Hammond & David Hopkins. 5 vols. London: Routledge, 1995-2005.

- Gavin Hopps

- Lord Byron. The Poems of Lord Byron: Don Juan. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Jane Stabler & Gavin Hopps. vols. 3-4 of 5. London: Routledge, 2024.

- Thomas A. Horrocks

- Abraham Lincoln. The Annotated Lincoln. Ed. Harold Holzer & Thomas A. Horrocks. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Paulo Lemos Horta

- Anon. The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights. Trans. Yasmine Seale. Ed. Paulo Lemos Horta. Foreword by Omar El Akkad. Afterword by Robert Irwin. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021.

- H. Montgomery Hyde (1907-1989)

- Oscar Wilde. The Annotated Oscar Wilde: Poems, Fiction, Plays, Lectures, Essays, and Letters. Ed. H. Montgomery Hyde. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1982.

- Mary Doody Jones

- L. M. Montgomery. The Annotated Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Ed. Margaret Anne Doody, Mary Doody Jones, & Wendy Barry. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Sunand Tryambak Joshi (1958- )

- H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. ["The Rats in the Walls," "Herbert West--Reanimator," "The Colour Out of Space," "The Dunwich Horror", "At the Mountains of Madness"] Ed. S. T. Joshi. Illustrations by Michael Lark. New York: Bantam Dell, 1997.

- H. P. Lovecraft. More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. ["The Picture in the House", "The Hound", "The Shunned House", "The Horror at Red Hook", "Cool Air", "The Call of Cthulhu", "Pickman's Model", "The Thing on the Doorstep", "The Haunter of the Dark"]. Ed. S. T. Joshi & Peter Cannon. Introduction by Peter Cannon. New York: Dell, 1998.

- H. P. Lovecraft. The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature: Revised and Enlarged. 1927. Ed. S. T. Joshi. 2000. New York: Hippocampus Press, 2013.

- Daniel Karlin

- Robert Browning. The Poems of Browning. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. John Woolford, Daniel Karlin, & Joseph Phelan. 6 vols of 7. London: Routledge, 1991-2010.

- Leslie S. Klinger (1946- )

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. Leslie S. Klinger, 3 vols (2005-6)

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes & The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. 1892 & 1894. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- The Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow & The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes. 1905, 1917 & 1927. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear. 1887, 1890, 1902 & 1915. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2006.

- Bram Stoker. The New Annotated Dracula. 1897. Edited by Leslie S. Klinger. Additional Research by Janet Byrne. Introduction by Neil Gaiman. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Inc., 2008.

- Neil Gaiman. The Annotated Sandman. 1988-1996. 4 vols: Issues #1-20 (2012); Issues #21-39 (2012); Issues #40-56 (2014); Issues #57-75 (2015). Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York: Vertigo, 2012-2015.

- H. P. Lovecraft. The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. Introduction by Alan Moore. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2014.

- Mary Shelley. The New Annotated Frankenstein: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. 1818. Rev. ed. 1831. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. Introduction by Guillermo del Toro. Afterword by Anne K. Mellor. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Inc., 2017.

- Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons. Watchmen: The Annotated Edition. 1986-87. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. Introduction by Dave Gibbons. New York: DC Comics, 2017.

- Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s. ['House Without a Key', by Earl Derr Biggers; 'The Benson Murder Case', by S. S. Van Dine; 'The Roman Hat Mystery', by Ellery Queen; 'Red Harvest', by Dashiell Hammett; 'Little Caesar', by W. R. Burnett]. Ed. & annotated Leslie S. Klinger. Introduction by Otto Penzler. New York: Pegasus Books, 2018.

- Neil Gaiman. The Annotated American Gods. 2001. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York: William Morrow, 2019.

- H. P. Lovecraft. The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft: Beyond Arkham. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. Introduction by Victor LaValle. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2019.

- Robert Louis Stevenson. The New Annotated Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger (2022)

- Arthur Conan Doyle. The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. Leslie S. Klinger, 3 vols (2005-6)

- Richard Leakey (1944-2022)

- Charles Darwin. The Illustrated Origin of Species. 1859. Abridged & Introduced by Richard Leakey. Consultants: W. F. Bynum & J. A. Barrett. London: Book Club Associates, 1979.

- Seth Lerer (1955- )

- Kenneth Grahame. The Wind in the Willows. 1908. Ed. Seth Lerer. Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Ronald Levao

- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. The Annotated Frankenstein. 1818. Ed. Susan J. Wolfson & Ronald Levao. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Stuart Levine

- Edgar Allan Poe. The Short Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe: An Annotated Edition. Ed. Stuart & Susan Levine. Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1977.

- Susan Levine

- Edgar Allan Poe. The Short Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe: An Annotated Edition. Ed. Stuart & Susan Levine. Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1977.

- Edna Longley (1940- )

- Edward Thomas. Poems and Last Poems (Arranged in Chronological Order of Composition). Ed. Edna Longley. 1917 & 1918. Collins Annotated Student Texts. London & Glasgow: Collins Publishers, 1973.

- Edward Thomas. The Annotated Collected Poems. Ed. Edna Longley. 2008. Highgreen, Tarset, Northumberland: Bloodaxe Books Ltd., 2011.

- Roger Lonsdale (1934-2022)

- Thomas Gray, William Collins & Oliver Goldsmith. The Poems of Thomas Gray, William Collins, & Oliver Goldsmith. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Roger Lonsdale. 1969. London: Longman Group Limited, 1980.

- Deidre Shauna Lynch

- Jane Austen. Mansfield Park. 1814. Ed. Deidre Shauna Lynch. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Raphael Lyne

- William Shakespeare. The Complete Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Cathy Shrank & Raphael Lyne. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Peter McDonald

- W. B. Yeats: The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Peter McDonald. 3 vols of 5. London: Routledge, 2020- .

- Raymond McNally

- Bram Stoker. The Essential Dracula: A Completely Illustrated & Annotated Edition of Bram Stoker’s Classic Novel. 1897. Ed. Raymond McNally & Radu Florescu. New York: Mayflower Books, 1979.

- Leonard S. Marcus (1950- )

- Norton Juster. The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth. Illustrated by Jules Feiffer. 1961. Ed. Leonard S. Marcus. Knopf Books for Young Readers. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

- John F. Marszalek

- Ulysses S. Grant. The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition. 1885. Ed. John F. Marszalek, with David S. Nolen & Louie P. Gallo. Preface by Frank J. Williams. Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass.:, Harvard University Press, 2017.

- Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson (1941- )

- Sigmund Freud. The Interpretation of Dreams: Illustrated Edition. 1900. Trans. A. A. Brill. 1913. Ed. Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. New York: Sterling Publishing Co. Inc., 2010.

- John Matteson (1961- )

- Louisa May Alcott. The Annotated Little Women. 1868-69. Ed. John Matteson. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2015.

- Christopher Matthew (1939- )

- Jerome K. Jerome. Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the Dog): Annotated Edition. 1889. Ed. Christopher Matthew & Benny Green. London: Pavilion Books, Ltd., 1982.

- Geoffrey Matthews

- Percy Bysshe Shelley. The Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Carlene Adamson, Will Bowers, Jack Donovan, Kelvin Everest, Geoffrey Matthews, Mathelinda Nabugodi, & Michael Rossington. 6 vols. London: Routledge, 1989-2024.

- David Mikics (1961- )

- Ralph Waldo Emerson. The Annotated Emerson. Ed. David Mikics. Foreword by Phillip Lopate. The Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass & London: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Walter James Miller (1918-2010)

- Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. The Only Completely Restored and Annotated Edition. ['Vingt mille lieues sous les mers', 1869-70]. Ed. Walter James Miller. New York: Thomas J. Crowell, Publishers, 1976.

- Jules Verne. The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon - Direct in Ninety-seven Hours and 20 Minutes. The Only Completely Rendered and Annotated Edition. ['De la Terre à la Lune, trajet direct en 97 heures 20 minutes', 1865]. Ed. & trans. Walter James Miller. New York: Thomas J. Crowell, Publishers, 1978.

- Robert Morrison (1961- )

- Jane Austen: Persuasion: An Annotated Edition. 1817. Ed. Robert Morrison. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Peter F. Neumeyer (1929- )

- E. B. White. The Annotated Charlotte’s Web. Illustrated by Garth Williams. 1952. Ed. Peter F. Neumeyer. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1994.

- Frances Partridge (1900-2004)

- Lytton Strachey. Eminent Victorians: The Illustrated Edition. 1918. Foreword by Frances Partridge. London: Bloomsbury, 1988.

- Stephen Peithman

- Edgar Allan Poe. The Annotated Tales of Edgar Allan Poe. Ed. Stephen Peithman. New York: Doubleday, 1981.

- Joseph Phelan

- Robert Browning: The Poems of Browning. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. John Woolford, Daniel Karlin, & Joseph Phelan. 6 vols of 7. London: Routledge, 1991-2010.

- David Quammen

- Charles Darwin: On the Origin of Species: The Illustrated Edition. 1859. Ed. David Quammen. 2008. Sterling Signature. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2011.

- Kurt A. Raaflaub

- Julius Caesar. The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works: Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War. Ed. & trans. Kurt A. Raaflaub. Series editor: Robert A. Strassler. Pantheon Books. New York: Random House, Inc., 2017.

- Jack N. Rakove (1947- )

- James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, et al. The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence. 1776 & 1789. Ed. Jack N. Rakove. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Theodore Redpath

- John Donne. The Songs and Sonets of John Donne: Second Edition. 1955. Ed. & annotated by Theodore Redpath. Belknap Press. Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Sir Christopher Bruce Ricks (1933)

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson: The Poems of Tennyson. Longmans Annotated English Poets. Ed. Christopher Ricks. London & Harlow: Longman, Green and Co, Ltd.. 1969.

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson: Tennyson: A Selected Edition. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Christopher Ricks. 1969. Revised ed. 3 vols. 1987. Selected Edition. 1989. Pearson Longman. Edinburgh Gate: Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

- Hollis Robbins (1963- )

- Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 1852. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Hollis Robbins. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2007.

- Robin Robbins

- John Donne. The Complete Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Robin Robbins. London: Routledge, 2010.

- James Romm

- Arrian: The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander / Anabasis Alexandrou. Ed. James Romm. Trans. Pamela Mensch. Introduction by Paul Cartledge. Series Editor: Robert B. Strassler. Pantheon Books. New York: Random House, Inc., 2010.

- Alfred Leslie Rowse (1903-1997)

- William Shakespeare. The Annotated Shakespeare: The Comedies, Histories, Sonnets and Other Poems, Tragedies and Romances Complete. Ed. A. L. Rowse. 3 vols. London: Orbis Publishing Limited, 1978.

- Comedies

- Histories and Poems

- Tragedies and Romances

- William Shakespeare. The Annotated Shakespeare: The Comedies, Histories, Sonnets and Other Poems, Tragedies and Romances Complete. Ed. A. L. Rowse. 3 vols. London: Orbis Publishing Limited, 1978.

- Elizabeth D. Samet

- Ulysses S. Grant. The Annotated Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. 1885. Ed. Elizabeth D. Samet. The Liveright Annotated American History Series. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2019.

- Yasmine Seale (1989- )

- Anon. The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights. Trans. Yasmine Seale. Ed. Paulo Lemos Horta. Foreword by Omar El Akkad. Afterword by Robert Irwin. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021.

- David M. Shapard

- Jane Austen. The Annotated Pride and Prejudice 1813. Ed. David M. Shapard. 2004. Anchor Books. New York: Random House Inc., 2007.

- Jane Austen. The Annotated Persuasion. 1817. Ed. David M. Shapard. Anchor Books. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2010.

- Jane Austen. The Annotated Sense and Sensibility. 1811. Ed. David M. Shapard. Anchor Books. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011.

- Jane Austen. The Annotated Emma. 1815. Ed. David M. Shapard. Anchor Books. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2012.

- Jane Austen. The Annotated Northanger Abbey. 1817. Ed. David M. Shapard. Anchor Books. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013.

- Jane Austen. The Annotated Mansfield Park. 1814. Ed. David M. Shapard. Anchor Books. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017.

- Daniel Shealy

- Louisa May Alcott. Little Women: An Annotated Edition. 1868. Ed. Daniel Shealy. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Cathy Shrank

- William Shakespeare. The Complete Poems. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Cathy Shrank & Raphael Lyne. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Nigel Smith (1958- )

- Andrew Marvell. The Poems of Andrew Marvell. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Nigel Smith. 2003. Revised Edition. Pearson Longman. Edinburgh Gate: Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

- Patricia Meyer Spacks (1929- )

- Jane Austen. Pride and Prejudice: An Annotated Edition. 1813. Ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Jane Austen. Sense and Sensibility: An Annotated Edition. 1811. Ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks. Belknap Press. Cambridge Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Jane Stabler

- Lord Byron. The Poems of Lord Byron: Don Juan. Longman Annotated English Poets. Ed. Jane Stabler & Gavin Hopps. vols. 3-4 of 5. London: Routledge, 2024.

- Philip Van Doren Stern (1900-1984)

- Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 1852. Ed. Philip van Doren Stern. Bramhall House. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1964.