[Rita Angus: "Portrait of Betty Curnow" (1942)]

[Rita Angus: "Portrait of Betty Curnow" (1942)]

NB: All images in this post come from Rita Angus: Life and Vision,

the website for the Te Papa exhibition running 5/7-5/10/2008Well,

Bronwyn and I had a fascinating time over the weekend. We flew down to Wellington to take part in the Rita Angus Symposium at Te Papa.

There were seven papers read in the course of the day, an Artists' Roundtable with Robin White, Seraphine Pick and Julian Dashper, chaired by exhibition curator William McAloon, followed by a chance to question him and the other curator of "Rita Angus: Life and Vision," Angus's biographer Jill Trevelyan. We started at 9 am, and went on till past five o'clock in the afternoon. The whole event was excellently organised by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, Director of Art and Collection Services at Te Papa.

The first signs of trouble started with the second paper in the morning session. Mary Kisler of the Auckland Art Gallery had just given an interesting paper about Angus's links with traditional European Old Master motifs, but then Prof. Wystan Curnow of the Auckland English Department set the cat among the pigeons by giving a paper mocking the various attempts which have been made to date to turn Angus's "Portrait of Betty Curnow" (1945) into an "iconic" (his inverted commas) image.

As I understand his argument, he detected a recrudescence of that old New Critical bugbear, the (so-called) "

intentional fallacy," in the readings of this painting. When it came to providing his own reading, though, it was hard to see what precisely he wanted to put in their place. "Let the painting speak for itself," he said. But doesn't that generally mean (in practice) let the licensed Art Critic speak for it?

I quite understand the problems of historicism when it comes to dominate criticism ("How many children had Lady Macbeth" etc.), but I don't myself see any way in which one can remove history - or at any rate the cultural history of styles - from

any interpretation of

any artistic artefact. In other words,

can one successfully take the history out of Art History and still have much left to talk about? Our categories of interpretation are so culturally determined and contingent, after all.

Jo Drayton and Professor Michael Dunn gave the next two papers in the morning session.

The afternoon session began with an interesting discussion of Angus's Hawke's Bay landscapes by Ron Brownson of the Auckland Art Gallery. Perhaps the most telling moment in his presentation came, however, when there was a question from the floor about the reception of Angus's late paintings.

"I can act it out for you," he said, and stood still for a moment.

"Silence. That was the reaction."

This formed the prelude to Bronwyn's paper, which I've reprinted in full below.

I don't know that I've ever seen anything quite so dramatic at an Academic gathering as the way this paper sorted the audience into two groups. On the one hand, most of the general public appeared to be moved and fascinated by Bronwyn's revelations about Angus and Lilburn's strange love-affair and its artistic aftermath. Some were actually in tears as she read out her short story "It goes like this Gordon," at the end. One girl in the audience exclaimed, "That lady rocked my day." Another lady leant across me to tell her friend that it was by far the best paper she'd heard so far.

But the Art Historians hated it. I guess they felt that it was biographical, not critical - and they tried to shoot it down with a series of objections and barbed queries. Bronwyn stood her ground, though. It is her PhD subject, after all, and nobody knows the ins-and-outs of Angus studies like she does (with the possible exception of Jill Trevelyan).

As a bit of a card-carrying New Historicist myself, I found it a bit hard to believe that Art Historians were still so rooted in the dogmas of mid-twentieth century criticism that they didn't understand that all that "affective fallacy" and "intentional fallacy" stuff was long since outmoded theoretically. Removing history from your argument simply means being a slave to alleged norms of cultural "meaning," as the post-structuralists should have taught us all by now. Isn't that the basic function of deconstruction, to remind us what slippery ground we're all standing on?

So when Wystan Curnow stood up to school this young whipper-snapper in the critical facts of life, I doubt he expected her to give him as good as she got. Wystan just doesn't think the Goddess paintings are any "good" (whatever

that means), but more to the point, he doesn't think that the exploration of personal symbolism is a valid way of explicating pictures.

Fair enough. I'm sure we'd all agree with him that it's not the only approach. But when you've had an archive of letters expounding in detail exactly what the artist thought she was up to, addressed to the one other person she was counting on to understand her, land in your lap, it would surely be foolish not to pay them some attention?

As an outsider to this field, I found it quite fascinating to watch this battle of the rival interpreters. That's what Academic symposia are for, after all, aren't they? I may well be misrepresenting some of the arguments, but I prefer to think that I'm just contextualising them within the debates rife in my own discipline of Literary Criticism.

Bronwyn's position (as I understand it) is basically a New Historicist one. She thinks that exploring an artist's stated intentions, unpacking all the clues and following up all the leads in her published and unpublished writings and statements is an excellent starting point for interpreting her works. We're in an unusually privileged position with Rita Angus and Douglas Lilburn, as Rita had to explain a lot of things to him, as a non-visual artist, which she might well have elided over in correspondence with another painter.

But Bronwyn is certainly

not claiming that this is the sole task of art critics. Certainly there are many other levels of interpretation which can be applied to paintings, including purely formal criticism of styles. Close study of contexts does not preclude the close examination of texts.

Wystan's position appears to be that these letters are no guide at all to the actual content of Rita Angus's paintings. They provide material for biographers and historians, not critics, who should confine themselves to painted surfaces and the history of styles.

And this is of course still the establishment view - at any rate in New Zealand Art History Departments (though not, I suspect, within the discipline as a whole). His position seems basically New Critical to me, though he might prefer to see it as Post-structuralist.

To me, then, the argument comes down to one question: Is it

ever worth listening to what artists have to say about their work, or should one treat them as inspired idiot savants, good at slathering on the paint but fatally biassed when it comes to interpreting their own creations? Taking their statements entirely at face value surely would be naive, but then that's not what an historian (or a New Historicist) does, I wouldn't have thought.

The alternative appears to be trusting that art critics know more about art than artists do, and I fear I just don't have that much belief in the acumen of my own profession.

The debate will no doubt continue. The gloves came off momentarily at this seminar. I'll be interested in hearing what some of the rest of you think about this issue.

Are there sacred bounds which interpretation may not venture across? The New Critics would have said so, but then it turned out that the categories they were relying on to introduce objectivity into the field were so culturally coded as to be virtually meaningless to non-Europeans and even (it seemed at times) non-Anglo-Saxons.

Personally I'd rather echo Abraham Lincoln's words - we can no longer live by the dogmas of the quiet past. We study history because we have to - if we're serious about learning more about the vast tides which agitate humanity, that is. One of those immense chaotic forces goes by the name of "Art."

[Rita Angus: "Portrait of Douglas Lilburn" (1945)]The Dream Children: Rita Angus’s Goddess Paintings

[Rita Angus: "Portrait of Douglas Lilburn" (1945)]The Dream Children: Rita Angus’s Goddess Paintings[Te Papa Symposium: 13 September 2008]

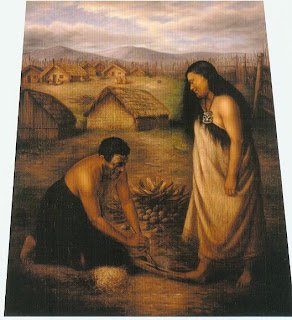

Rita Angus’s own description of the ideal way to present her art has determined the structure of the ‘Rita Angus Life & Vision’ exhibition, beautifully curated by Jill Trevelyan and William McAloon. Angus’s friend John Money recalled that she imagined her work displayed as a ‘kind of temple of art’ with her three Goddess paintings at the centre surrounded by a series of small chapels containing smaller paintings and watercolours related one to the other.

In this paper I want to look at why Angus envisaged the Goddess paintings at the centre of her temple of art. I believe that she was inviting us to inhabit the imaginative core of her creative world through the understanding of her three imaginary Goddess portraits: her trio of immortals.

To begin to understand the Goddess paintings we must first acknowledge two incontrovertible facts: That Rutu is not a self-portrait, idealised or otherwise, and that the Sun Goddess and Rutu are Angus’s imaginary children and in her mind they were real and very much alive.

If we can come to terms with these facts then we will realise that this is a very powerful temple indeed, because there inside it Rita Angus has placed her successors and her legacy to future generations.

•

When Angus died in 1970, these two paintings were among a lifetime's work that survived her. The secret of their identity as her imaginary children, however, the artist took with her to the grave. Documentary evidence of the imaginary lives of Angus's two painted Sun Goddesses is contained, as we now know, in an archive of some 400 letters written by Angus to the man she regarded as the father of her dream children, acclaimed New Zealand composer Douglas Lilburn, who bequeathed the correspondence to the Alexander Turnbull Library.

Through his bequest Lilburn posthumously revealed the hitherto unknown emotional and intellectual complexity of his 28 year friendship with Rita Angus, which included the story of their love affair at the end of 1941, the pregnancy that resulted and a miscarriage suffered by Angus in January 1942 as well as the remarkable story of the two dream children that their relationship generated.

'I have wanted to make a work of art of our relationship’ Angus wrote to Lilburn in 1943, ‘as much as is possible, I think so'. The two qualifiers used by Angus here render her motivating intention less absolute and signal from the outset that there were limits imposed on such an undertaking. The sexual and marital proprieties presiding over her era prevented Angus, a divorced woman artist, from giving full and open expression to the story of her love affair with Lilburn and the loss of their illegitimately conceived child, and from using this as a legitimate subject in her painting. Her desire to do so, however, continued unabated. ‘I have been in love with you,’ she wrote to Lilburn, ‘and it will be expressed in paint’.

If Angus wanted to tell this story in her art, and it is clear that she did, then the subject would have to be approached covertly, and for this she would need to find the right painterly language. What she arrived at was a method of painting in symbols and one in which two stories, a public and a private story, could exist on a single canvas. In order to tell a story that was simply unacceptable in her own time she had to hide or veil the personal and subjective, painting it into her compositions as one private layer of symbolism among other publicly accessible symbolic motifs. In short, Angus elaborated an art of subterfuge.

[Rita Angus: "Douglas Lilburn" (1944-50)]

[Rita Angus: "Douglas Lilburn" (1944-50)]

She began with the Lilburn oil portrait in 1944, which was abandoned incomplete some ten years later. In this portrait, Angus wanted to represent the composer’s daemon: the very source and spirit of his creativity. She attempted to convey this through his expression of quiet repose, the strong line of his shoulders, which carried the hope of the world, and the qualities of honesty and humility in the position of Lilburn’s hands, for which Angus made numerous pencil studies. The tombstones painted in the work were a symbol of the violent conquests of man, and the group of anthropomorphic rocks, a representation of time. Lilburn’s creative power as a composer was symbolised by the majestic mountain range that formed the background to the portrait.

[Rita Angus: "Rutu" (1945-51)]

[Rita Angus: "Rutu" (1945-51)]

Shortly after Angus began the Lilburn portrait she had a dream and in it her first dream child, a Sun Goddess, later named Rutu, was born.

You may remember my dream, the latter part, of a child in the likeness of my father. Last Saturday week, I awoke with the idea of making this image, a sketch. I began with the water colour of my Father before me, and your portrait at the end of the room. My memory served me well, about three hours later a child about 16 or 17 years of age, like my family, but not mine; she belongs to you. Of European birth, simple, monastic, Western schooling, you will find her in the paintings on the walls of the Temple Caves of India, where wandering Yogi priests sheltered, in the Bodhisattas of the Buddhist shrines where the Chinese worshipped in the flower and tea ceremonies of the Samurai. The Geisha and the Priestesses of the Shinto shrines of Japan.

•

The Lotus

Angus had seen reproductions of the masterpieces of Buddhist art adorning the Ajanta caves in India. One of these, a galloping elephant, she incorporated into her marvellous pacifist portrait of Lawrence Baigent but another much reproduced image from the central shrine of the first Ajanta cave, an image of the Bodhisattva Padmapani, a serenely beautiful youth holding a white lotus, may well have been one of the inspirations for Rutu. Her reference to the Shinto shrines of Japan is also significant given that the most important Shinto shrine in Japan is the Ise shrine dedicated to the deity Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, her name meaning that which illuminates heaven. The white lotus or waterlily held by Angus’s first Sun Goddess Rutu is also an Egyptian motif, homage to an ancient civilisation greatly admired by Angus for the advanced social status enjoyed by women.

Over time Rutu became much more important to Angus than the sum of her many symbolic parts: ‘The 'Sun Goddess' is your child’, she wrote to Lilburn, ‘She is mine. The waterlily is painted.’

[Rita Angus: "Sun-Goddess" (1946-49)]

[Rita Angus: "Sun-Goddess" (1946-49)]

In 1946 Angus’s second Sun-Goddess appeared in watercolour. She is a Western Goddess holding a white orchid and standing in the foreground of a bushclad landscape densely planted with hydrangeas, orchids, shrubs and trees. Angus described the auspicious event in her letters to Lilburn. ‘She is beautiful, and brings peace. The Sun Goddess has come to earth. She 'lives'.’

[Rita Angus: "A Goddess of Mercy" (1945-47)]

[Rita Angus: "A Goddess of Mercy" (1945-47)]

Angus's painting, A Goddess of Mercy, sits chronologically between the two Sun Goddesses. She is a kindred work to the Sun Goddesses, although she is not one of Angus’s dream children. She is a young woman holding a single yellow crocus who delivers a message of mercy and compassion to the world. 'This year,' Angus wrote to Leo Bensemann in 1947, 'I exhibit 'A Goddess of Mercy' in memory of my sister, Edna, who died in December, 1939. Most of the idea of this painting was blocked in, just before and during, the week peace was declared with Europe. It is the pull between life and death, with the triumph of the living over the dead. 'Ruth' is the woman, and the painting 'lives'.

Angus’s repeated insistence that the Goddess paintings ‘live’ is an important part of the story. Few fictional or factual accounts of imaginary children invented in adulthood exist, perhaps because it is a subject teetering on the knife-edge of fantasy and madness, and presenting too disquieting a combination of the real and the unreal for us to openly or comfortably acknowledge. Edward Albee’s play, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Robin Hyde’s fantasy novel, Wednesday’s Children, are two very powerful fictitious stories about dream children. Factual accounts of imaginary children suggest that the creation of fictive offspring generally stems from the desire to fill the void of childlessness arising either from the experience of losing a child or the sorrow caused by the inability to conceive one. Rita Angus and Katherine Mansfield were two prominent New Zealand women who had such a story in common.

Angus’s experience of pregnancy, although brief, was deeply spiritual and transformative. In her mind the developing child inside her was inextricably bound to her artistic creativity. In letters written to Lilburn before the miscarriage she described her heightened powers of perception and how pregnancy had brought the two parts of herself, the painter and the woman, into alignment:

In the months following the miscarriage Angus reflected on the way that her pregnancy had awakened within her a sense of life’s continuity, which she was attempting to harness and channel into her painting. ‘There's life in my painting of some flowers in water colour’, Angus wrote. ‘I sense the child, I loved the child.’ Her heartfelt reflection is immediately followed by a quotation from The Meditations of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius: 'Love that which happens to thee and is spun with the threads of thy destiny. For what is more suitable?' (23 June 1942, MS-P-7623-050).

Were Angus’s words an offering of assurance to Lilburn that she had emotionally recovered from the miscarriage? Was she attempting to comfort herself in the knowledge that the experience of losing a child must have some higher purpose or value, or did she really believe that the loss of the child was somehow fated? A definitive answer to these questions is not possible but the appearance of her first painted dream child two years later suggests that the spirit of her lost child was an ongoing presence in her life and was to some extent directing the course of her painting.

In 1919, Katherine Mansfield, dying of tuberculosis, was beset by a desperate longing to have a child with her husband, John Middleton Murry. Her dream of motherhood went unfulfilled but an imaginary child was invented to fill the maternal void. Mansfield’s deteriorating health compelled her to leave England for the Mediterranean while Murry remained behind to manage their financial affairs. Her loneliness, depression, and illness only increased her desire for a child, so she imagined one, sometimes a daughter, sometimes a son named Dickie who is mentioned a number of times in her letters from this period. Murry whole-heartedly supported the creation of the dream child as a surrogate before the arrival of their own longed for child. Towards the end of 1919 Mansfield wrote to her husband:

We MUST have children - we MUST. I want our child - born of love - to see the beauty of the world - to warm his little hands at the sun & cool his little toes in the sea. I want Dickie to show things to. Think of it! Think of me dressing him to go for a walk with you. Bogey we must hurry - our house - our child - our work.

In C K Stead’s selected edition of Mansfield’s journals and letters, a journal entry from 1919 describes one of a series of almost hallucinatory dreams that Mansfield was experiencing around that time and which she considered to be the one positive side effect of her illness. In the dream she is on an ocean liner late at night walking on deck with her father. A break in the journal entry suggests a shift of scene in her dream and suddenly she is undergoing a medical examination:

‘Any children?’ he asked, taking out his stethoscope, as I struggled with my nightgown.

‘No - no children.’

But what would he have said if I had told him that until a few days ago I had had a little child aged five and three-quarters - of undetermined sex. Some days it was a boy. For two years now it had very often been a little girl. (162)

In Stead’s historical novel Mansfield he imaginatively reconstructs Katherine Mansfield’s life during the First World War. The subject of Mansfield’s dream child is raised in the novel as part of a private exchange between Mansfield and English artist Dora Carrington in which Carrington discloses that she secretly imagines herself as a man and Mansfield reveals in return that she secretly imagines herself as a mother:

Katherine’s face was so kind, so comprehending, Carrington found herself saying, “Mansfield, would you mind very much…Pretending, you know?”

‘That you’re a chap? I’m doing it already. You’re a chap.”

Carrington laughed. “Am I? Are you sure?”

“Absolutely certain. You’re a chap, and I’m a mother.”

“Oh yes you are. I’ve seen your little girl…”

“Boy,” Katherine corrected. “She was a girl last week, but this week she’s a boy.”

“I say, isn’t it nice that it can change.” (161)

When Middleton Murry purchased a cottage in the Sussex countryside in 1920 he hoped that he and Mansfield would fulfil their dream of a family and writing life. Murry wrote to his wife about the ‘two little daisy children’ they would have when they settled in their new home and Mansfield replied: ‘Oh Destiny, be kind. Let this be. Let these two children live happily ever after. Sadly, the dream did not eventuate. Mansfield never lived to see the Sussex cottage and their two ‘daisy children’ were never to be born.

The air of sentimentality and longing that pervades the characterisation of Katherine Mansfield’s dream children is the vital point of difference between them and Rita Angus’s two imaginary children. Mansfield’s children are innocents, inhabiting the role of loved and longed for children. While the loss of Rita Angus’s child was certainly the catalyst for the development of the Sun Goddesses, they emerged on the canvas, not as innocent children, but as fully formed young women, with the pacifist, feminist, and cultural role they were to play in the world painted into every aspect of their being.

A dream child is a unique creation, the fabric of the child's identity woven entirely from the imagination of its parents. A dream child can grow and develop from infancy through to adulthood. Dream children experience life, they develop personality and character traits, interests and beliefs, and their lives unfold in much the same way as real children's do.

Rita Angus’s Sun Goddesses developed an interest in anthropology. They thrived on the praise they received from visitors. They sent their love to Lilburn and asked to hear his music – especially the Allegro which Angus felt contained the spirit of her lost child. Rutu travelled abroad before Angus herself did to take part in an exhibition of NZ art in London organised by Helen Hitchings and a strange custody battle ensued between Angus and Lilburn upon her return because they both longed so much to see Rutu again.

The fact that only one side of the correspondence between Angus and Lilburn survives means that there are many elisions in the narrative of the lives of the Sun Goddesses. While Angus’s role as mother and creator of the dream children dominates the story the letters suggest that Lilburn was a willing participant in the fantasy, and that he accepted his role as father to the Sun Goddesses and actively contributed to their development. Much of the story of the dream children, I suspect, exists outside the pages of the letters, in the many conversations shared between Angus and Lilburn in the presence of the Sun Goddesses. A letter written by Angus to her sister Jean mentions one such private exchange between Angus, Lilburn, and their firstborn dream child:

Dear Jean

Many happy returns of the day. I intended to send you a wire but I did not go down to the village. Gordon came unexpectedly to lunch and we meditated with the Sun Goddess.

What was said between Angus and Lilburn during occasions such as this will never be known to us. As a consequence Angus’s written account of the lives of the Sun Goddesses presents us with only a partial narrative. The story of the Sun Goddesses spans a period of eleven years in the correspondence from 1944-55. The most detailed account of the dream children’s development occurs during the first five years of this period. Following the severe nervous breakdown suffered by Angus at the end of 1949 it appears that the fantasy became increasingly difficult to sustain on the part of both Angus and Lilburn. References to the Goddesses beyond this date are sporadic, the imaginative construction of their lives dissipates, and they are seldom mentioned at all in letters beyond 1955.

•

The story recounted by Angus in the letters is one of loss and love, transformed through artistic invention into a fantasy family. Angus's inclusion of the Goddess paintings in particular exhibitions and publications opens up the possibility for a fascinating contextual analysis in light of the revelation that she was displaying her children. Furthermore, the extremity of responses by both Angus and Lilburn to less than positive reviews and opinions about the Goddesses by third parties, not privy to the secret of their identity, reveals a great deal about the challenge of sustaining a fantasy family. For a brief period parental pride and devotion to the Sun Goddesses characterised the letters but a growing undercurrent of tension between Angus and Lilburn inevitably led to a dénouement and the unravelling of the fantasy.

It’s clear that for Lilburn the dénouement came in 1947 after he took his friend Charles Brasch to view the Goddess paintings at Angus’s Clifton cottage. Brasch didn’t like the Goddess paintings at all and he found very little to say during the visit which upset Lilburn enormously. Brasch recounted in his journal that while they waited for the train home Lilburn asked, ‘was I not going to say anything about the pictures, adding quietly but provocatively that if we could not talk about these we could not remain friends - I ignored this last & said that of course we could talk about them & went on to say what I felt about the paintings, that they - or rather it, the Sungoddess, was unreal with a kind of obsessional intensity but no life.’ This statement must have cut Lilburn to the quick and Brasch remarked that on the journey home ‘Douglas seemed really hurt - wounded, by my attitude.’

In response to Brasch’s critique of the Goddesses it seems that Lilburn spoke to Angus encouraging her to focus more on her landscapes rather than her portrait painting, a suggestion to which she responded angrily in writing:

Well, to tell you, I didn't accept your wishful speaking, I am too interested in portraying people, and if you, too, were more rational you could realize that I have variable abilities and, have been well schooled in many branches of painting, portraits, figure composition as well as landscape. (I've heard this attitude of mind towards me, as a landscape painter for more than 10 years now, I am sorry you cannot think for yourself)

Words don't unpaint paintings nor paint them. Line and colour do.

Though you are a musician (and one who does not paint) you astonish me, you have visited me, and are one of the few, privileged to see my mature and recent painting grow, works that I have been seriously devoted to for some years. You have not had the courtesy to see the truth. It is no longer important to me that you don't wish to see, you do not bind me with your narrow restrictions upon my artist freedom which you do not, and cannot possess. The spirit of woman is not crushed.

While her spirit may not have been crushed, Lilburn’s apparent desire to opt out of the psychological contract established between he and Angus and their imaginary offspring highlighted the fact that such a contract is binding only for as long as the parent or parents elect to keep the fantasy alive. It is a tenuous existence for the child, doubly so in the case of a two-parent family, where the child's life depends on the ability of the two adult participants in the shared fantasy to maintain the fragile balance between their kindred and competing desires. If one parent reneges on the contract the child is lost.

For Angus the unravelling of the fantasy came in a dream which she described in a letter to Lilburn:

Last night's dream I heard your 'Sonatina for Clarinet & Piano.' The clarinet was beautiful. Also I was in a large room, fire had gutted it, my haversack was half burnt & I couldn't find the 'Sun Goddess.' She was missing, she was burnt, she was ashes. I accepted. There was nothing to be done about it. I awakened to see the 'Sun Goddess' on my wall this morning. To me, my dream means the end of symbolism, and the beginning of a new abstraction, hearing the music.

As you will no doubt appreciate the story of Rita Angus’s dream children is a difficult one to tell. In many ways it is a very sad love story but out of the sadness and loss something amazing and beautiful emerged. It would be something of an understatement to say that at times over the past three years I have found the weight of the archive of Angus’s letters to Lilburn overwhelming. In a moment of research anxiety I composed a short cri de coeur addressed to Lilburn, known to his friends as Gordon, which summarises my response to the story of the Sun Goddesses. I would like to end by reading it to you.

•

It goes like this Gordon

For 28 years she tried to tell you that her peasant heart belonged to you. When you said you didn't want it she went inside her mind and made you her dream. When that wasn't enough she went inside her mind and made you a child. She made up a child with golden hair, fish swimming around her neck, and a lotus flower just starting to open in her hands.

She made you a Goddess, a daughter of the sun, for the daughter or son that she never had and neither did you.

And you're gone now Gordon but you left behind the 400 letters with her 28 years of questions and anger and devotion. You left them behind and now I'm reading them as if I'm you and I'm trying to understand what she was saying, only she wasn't saying it to me. And I'm reading all the books she recommended to you, the ones she thought would show you the way to understand her. I hope you read them too.

She tried to paint your daemon once but you kept shutting her out, you kept hiding your daemon from her because you didn't want her to find it, to really find it. After a while she gave up and made a cut through your left ear and across your throat and she painted out your face. It was a desperate act but you didn't see.

You took your friend Charles to meet the daughter she had made up just for you and he didn't see it either. He looked and he looked but he had no words. All he saw was Rita's face looking back at him and he was scared. And because he saw nothing and he said nothing he made you feel foolish for believing that she was real, that she was Rita's Mona Lisa, that she was your child. And you ran off down Aranoni Track, Gordon, and you were so angry at Charles and he couldn't understand why because he didn't know that she was your child and that he had been rude.

She made another daughter for you Gordon, a second Sun Goddess, so beautiful, with her halo and her flower. She hid parts of you in her face. You were there in her face all along.

Rita's dream caught fire. Your first daughter was burnt and there were only ashes but then Rita woke up and saw her there, your daughter, shining at her from the bedroom wall. It was an end though.

You wrote something to her once about lessons to learn for which there's no guidance except in myth and parable. In art these things have meaning, you wrote. She quoted your words back to you to reinforce the point. She had made a myth just for you Gordon.

Don't get me wrong, I know you tried, you tried really hard. You were kind. You made an offering of part of a chicken in her shrine once and she read too much into that. She read too much into everything you did. You sent her Rilke and she took his advice about solitude. You sent her The Life and Times of Po Chü-i with the sapphire cover and the gold letters. She loved that book. You sent her to Otago to make you a painting.

But she gave you two daughters - two daughters for you.

I'm going to take care of her kids now Gordon.

You just rest.