Edmund Crispin: The Glimpses of the Moon (1977)

Edmund Crispin: The Glimpses of the Moon (1977)"Under another name, he's a sort of male C. V. Wedgwood"

- The Glimpses of the Moon, pp. 74-75.

Between 1944 and 1955, promising young British composer Bruce Montgomery published eight detective novels and one collection of short stories under the pseudonym 'Edmund Crispin'. He also sold 38 stories to a variety of periodicals in Britain and the USA.

Most of these narratives featured the eccentric Academic Gervase Fen, Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Oxford, as their presiding sleuth.

After that there was a long silence until his final novel, The Glimpses of the Moon, appeared in 1977, the year before his death. It was followed by a further collection of short stories, Fen Country, which completed the canon.

'There goes C. S. Lewis,' said Fen suddenly. 'It must be Tuesday.'

'It is Tuesday.' Sir Richard struck a match and puffed doggedly at his pipe.

- Swan Song, p.60.

Why does he interest me so? Is it the minute portrait his books convey of an austerity Britain, first in the grip of wartime rationing, then of post-war shortages? Is it the constant barrage of in-jokes, comprehensible only to those familiar with such contemporary cultural icons as C. S. Lewis and C. V. Wedgwood? Or his ornate, orotund style of writing?

"An undergrad left an essay for you. I've been reading it. It's called - Sally puckered up her attractive forehead - 'The influence of Sir Gawain on Arnold's Empedocles on Etna'."

"Good heavens," Fen groaned. "That must be Larkin: the most indefatigable searcher-out of pointless correspondences the world has ever known."

- The Moving Toyshop, pp.110-11.

As well as all that, there's the 'Movement' connection. He was up at Oxford at the same time as Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, and the pair were initially hugely impressed by his effortless cosmopolitan airs and (initial) success with publishers, only to become increasingly carping and bitchy about him and his work as their own social and literary prestige mounted into the stratosphere.

So, yes, there's a good deal of gossip about him and his ways to be gleaned from their respective memoirs and biographies and collections of letters. If you read that kind of thing, that is. Which I do (obviously).

She talked about murder as she might have talked about the weather - being far too selfish, thick-skinned and unimaginative to see the implications either of that final, irrevocable act or of her own position.- The Moving Toyshop, p.105.

One of things that interests me most about the Montgomery / Crispin books is Gervase Fen himself. Not that Fen is a well-developed character. On the contrary, as I read my way through the books as a teenager, I was struck by how well portrayed and accurately placed most of the other people are, and how bizarrely unfocussed is Fen. It's almost as if the more we hear about him, the less there he is. His age seems fixed around 40, regardless of what year it is, and his Academic position at Oxford remains essentially unchanged throughout.

I don't know if this was intentional or not. I've sometimes wondered if it's connected to Crispin's unusual focus on the consequences of crime. His victims are not the cardboard cut-outs of an Agatha Christie or even a Dorothy Sayers, but living, breathing people, whose brutal deaths leave a gap in the world. It's as if he can't quite bring himself ever to forget the morality of the spectacle he's creating, however frivolously it may be framed.

Some of my taste for his work undoubtedly comes down to a similar taste in books. M. R. James is a persistent influence on Crispin throughout: most notably in the long description of the maze in Frequent Hearses, but also in the inset ghost story in his very first novel, The Case of the Gilded Fly, and the macabre goings-on in the cathedral in Holy Disorders.

He's also very well acquainted with the highway and byways of 17th and 18th century English poetry, which provide a good many of his titles - as well as most of the numerous epigraphs scattered through his pages.

In the last, longest and probably least focussed of his books, The Glimpses of the Moon, there's an illuminating aside by Fen, who's been forced by the insolvency of his publisher to abandon the book on modern British novelists he's been working on in a desultory manner throughout the whole narrative:

Fen pondered this; and the more he pondered it, the more he liked it. Some of the reading had been enjoyable, of course - The Doctor is Sick, I Want It Now, 'the Balkan trilogy', Elizabeth Bowen, The Ballad and the Source. But much more had not - and a great deal that was pending wasn't going to be either. [p.270]It's typical of Crispin that this passage will mean very little to anyone unfamiliar with the fiction of this period. I can't claim to have read all of the books on his list, but I have to say that this small selection seems to me very much on the money.

Let's see then. In strictly alphabetical order, reference is being made to:

- Amis, Kingsley. I Want It Now. 1968. London: Panther Books, 1969.

- Bowen, Elizabeth. The Collected Stories of Elizabeth Bowen. 1980. Introduction by Angus Wilson. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- Burgess, Anthony. The Doctor is Sick. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

- Lehmann, Rosamond. The Ballad and the Source. London: Collins, 1944.

- Manning, Olivia. The Balkan Trilogy. Volume One: The Great Fortune / Volume Two: The Spoilt City / Volume Three: Friends and Heroes. 1960, 1962 & 1965. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

The Doctor is Sick is one of four novels written by Anthony Burgess during his 1960 annus mirabilis, shortly after receiving a (later rescinded) sentence of death from his doctors. By far the most famous of these is A Clockwork Orange, but I'd already clocked The Doctor as by far the most entertaining of the bunch even before reading Crispin.

Kingsley Amis, too, is an author whom I've read both in bulk and in depth. I Want It Now is certainly not one of his most celebrated novels - no Lucky Jim or One Fat Englishman - but it is, again, quite exceptionally fun to read even in so impressive a line-up of hits.

As for The Balkan Trilogy, I've always been glad that this casual reference by Crispin inspired me to track it down and read it a number of times before it achieved temporary apotheosis as a TV miniseries with Kenneth Branagh and Emma Thompson. It is quite wonderfully moving and good, I think - far better than the follow-up, The Levant Trilogy. Nor did the TV adaptation really do it justice.

I suppose that it shouldn't really come as a surprise that Crispin was so astute and pleasure-of-reading-focussed a critic. His distinguished series of anthologies of SF, crime, and horror stories did a great service to the dissemination of each of these forms on the UK literary scene, in particular. But they travelled as far as little ol' New Zealand, too.

As John Clute puts it in his magisterial Encyclopedia of Science Fiction:

Crispin's work in sf Anthologies was of great influence. When Best SF (1955) appeared it was unique in several ways: its editor was a respected literary figure; its publisher, Faber and Faber, was a prestigious one; and it made no apologies or excuses for presenting sf as a legitimate form of writing. Moreover, Crispin's selection of stories showed him to be thoroughly familiar with sf in both magazine and book form, and his introductions to this and succeeding volumes were informed and illuminating ... It would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of the early volumes in this series in working towards the establishment of sf in the UK as a respectable branch of literature.

All I can add is that it was in one of his Tales of Terror anthologies that I first encountered Elizabeth Jane Howard's classic ghost story 'Three Miles Up', and for that I remain eternally grateful.

-

Novels:

- The Case of the Gilded Fly [US title: Obsequies at Oxford] (1944)

- The Case of the Gilded Fly. 1944. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1946.

The wartime production of a new play in Oxford is disrupted by the murder of one of the actresses. The novel includes a set-piece recounting of a ghost story by an old Don very much in the style of M. R. James.

- Holy Disorders (1945)

- Included in: The Second Gollancz Detective Omnibus: Whose Body?, by Dorothy L. Sayers / The Weight of the Evidence, by Michael Innes / Holy Disorders, by Edmund Crispin. 1923, 1943 & 1945. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1952.

A series of sinister murders by Nazis in a cathedral town are counterpointed by an old ghost legend about an organ loft.

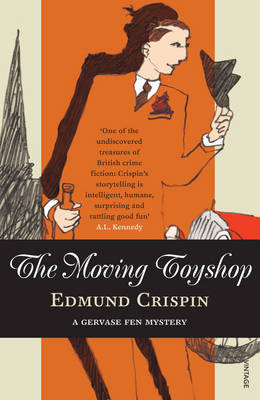

- The Moving Toyshop (1946)

- Included in: The Gollancz Detective Omnibus: The Moving Toyshop, by Edmund Crispin / Appleby’s End, by Michael Innes / Unnatural Death, by Dorothy L. Sayers. 1946, 1945 & 1927. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1951.

A Chestertonian poet goes looking for adventure, but ends up being coshed over the head in a toyshop in Oxford.

- Swan Song [US title: Dead and Dumb] (1947)

- Swan Song. 1947. A Four Square Crime Book. London: The New English Library Limited, 1966.

A postwar production of Wagner's Die Meistersinger is plagued with problems - including the suicide (or is it murder?) of one of the principal singers.

- Love Lies Bleeding (1948)

- Love Lies Bleeding. 1948. Penguin Crime Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

An invitation to present prizes at a girl's school puts Fen on the trail of a Shakespearean discovery of epoch-making importance. Will Love's labours finally be won?

- Buried for Pleasure (1948)

- Buried for Pleasure. 1948. Penguin Books 1292. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1958.

Fen stands for Parliament in a rural district. Halfway through the campaign he realises he doesn't want the job.

- Frequent Hearses [US title: Sudden Vengeance] (1950)

- Frequent Hearses. 1950. Penguin Crime Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

A loving tribute to the postwar British film industry - for which Bruce Montgomery composed so many scores - in the unlikely form of an abortive bio-pic about Alexander Pope.

- The Long Divorce [US title: A Noose for Her] (1951)

- The Long Divorce. 1952. Penguin Books 1304. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961.

Someone is sending poison-pen letters in the small village where Gervase Fen is temporarily domiciled. Could something so trivial have led to murder?

- The Glimpses of the Moon (1977)

- The Glimpses of the Moon. 1977. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

Fen is on sabbatical in a small Devon village plagued by a series of gruesome murders and dismemberments. A rich cast of characters are permitted to indulge their eccentricities to the utmost, until the actual murders become perhaps the least notable feature of the book.

- Beware of the Trains (1953) [BT]

- Beware of the Trains

- Humbleby Agonistes

- The Drowning of Edgar Foley

- Lacrimae Rerum

- Within the Gates

- Abhorred Shears

- The Little Room

- Express Delivery

- A Pot of Paint

- The Quick Brown Fox

- Black for a Funeral

- The Name on the Window

- The Golden Mean

- Otherwhere

- The Evidence for the Crown

- Deadlock

- Beware of the Trains. 1953. Penguin Classic Crime. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

- Fen Country (1979) [FC]

- Who Killed Baker?

- Death and Aunt Fancy

- The Hunchback Cat

- The Lion's Tooth

- Gladstone's Candlestick

- The Man Who Lost His Head

- The Two Sisters

- Outrage in Stepney

- A Country to Sell

- A Case in Camera

- Blood Sport

- The Pencil

- Windhover Cottage

- The House by the River

- After Evensong

- Death Behind Bars

- We Know You're Busy Writing, But We Thought You Wouldn't Mind If We Just Dropped in for a Minute

- Cash on Delivery

- Shot in the Dark

- The Mischief Done

- Merry-Go-Round

- Occupational Risk

- Dog in the Night-Time

- Man Overboard

- The Undraped Torso

- Wolf!

- Fen Country: Twenty-Six Stories. 1979. Penguin Crime Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

- Best SF (1954)

- Best SF: Science Fiction Stories. 1954. London: Faber, 1962.

- Best SF 2 (1956)

- Best SF Two: Science Fiction Stories. 1956. London: Faber, 1964.

- Best SF 3 (1958)

- Best SF Three: Science Fiction Stories. 1958. London: Faber, 1963.

- Best SF 4 (1961)

- Best SF Four: Science Fiction Stories. 1961. London: The Science Fiction Book Club, 1962.

- Best SF 5 (1963)

- Best SF Five: Science Fiction Stories. 1963. London: Faber, 1971.

- Best SF 6 (1966)

- Best SF 7 (1970)

- Best Detective Stories (1959)

- Best Detective Stories 2 (1964)

- Best Tales of Terror (1962)

- Best Tales of Terror. 1962. London: Faber, 1966.

- Best Tales of Terror 2 (1965)

- The Stars And Under: A Selection of Science Fiction (1968)

- Outwards From Earth: A Selection of Science Fiction (1974)

- Best Murder Stories (1971)

- Best Murder Stories 2 (1973)

- Whittle, David. Bruce Montgomery / Edmund Crispin: A Life in Music and Books (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Group, 2007)

Short Story Collections:

Edited:

Secondary: