August Derleth. The Solar Pons Omnibus. 2 vols. Ed. Basil Copper. Drawings by Frank Utpatel. Foreword by Robert Bloch. A Mycroft & Moran Book. Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House Publishers, Inc., 1982.

The other day I ran across this strange pair of volumes in a local secondhand bookshop. Solar Pons? Who on earth could that be? I was, of course, familiar with the name of the author, August Derleth, from my extensive reading of the late H. P. Lovecraft, whose literary executor he was ... or claimed to be.

"Solar Pons", though ... "pons" is the Latin word for bridge, and "solar" for all things pertaining to the sun. Was the intention, perhaps, to suggest some kind of Bifrost-like bridge leading to enlightenment?

Richard Lancelyn Green, ed.: The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1985)

Richard Lancelyn Green, ed.: The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1985)"God said: Let Sherlock be! and all was light ..."

- John Masefield

But enough of this trifling. "Solar Pons" is an avatar of "Sherlock Holmes", as I knew already from a scatter of references here and there. He isn't included in Richard Lancelyn Green's classic anthology The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, as that collection is confined solely to stories using the original names.

But then that was Derleth's original intention, too:

On hearing that Doyle did not plan to write more Sherlock Holmes stories, the young Derleth wrote to him, asking permission to take over the series. Doyle graciously declined, but Derleth, despite having never been to London, set about finding a name that was syllabically similar to "Sherlock Holmes," and wrote his first set of pastiches in 1928, which were published in The Dragnet Magazine in 1929.- Wikipedia: Solar Pons

We've certainly become rather accustomed to updated film and television versions of Sherlock Holmes over the past couple of decades.

And if you're tempted to query the presence of Dr. House in this grouping, what can one say of a man whose best friend is called "Wilson" (= Watson), and who's segued from a consulting detective to a consulting diagnostician? In any case, I've canvassed that subject extensively here.

Of the other three pictured above: Robert Downey Jr's steampunk version of Holmes; Benedict Cumberbatch's excessively cerebral, almost Alan Turing-like incarnation of the great man; and Jonny Lee Miller's New York-based junkie impersonation of the detective, I'm rather surprised to put on record here that at present it's Jonny Lee Miller who scoops the prize for me.

No doubt that has something to do with a serendipitous pairing with the dazzling Lucy Liu, definitely the most impressive Watson to date - so much better than Martin Freeman's petulant misery-guts, or even Jude Law's no-nonsense action man. In any case, for those of you who haven't seen it, Elementary is a very satisfying exercise in suspension of disbelief.

So what's next? Sherlock Holmes on ice? With an eventual total of 154 episodes, Jonny Lee Miller is now (according to Wikipedia) "the actor who has portrayed Sherlock Holmes the most times in television and/or film, overtaking Jeremy Brett (with 41 television episodes) and Eille Norwood (with 47 silent films)."

It may, however, interest you to know that Derleth wrote "more stories about Pons than Conan Doyle did about Holmes." Doyle wrote four novels and 56 short stories about Holmes, whereas Derleth wrote more than seventy stories (plus a couple of novels) about Pons.

There are obvious similarities between the two. Pons lives at 7B Praed Street; Holmes at 221B Baker Street. Pons' companion in crime is called Dr. Parker; Holmes's Dr. Watson. Pons' landlady is Mrs. Johnson; Holmes's Mrs. Hudson. Pons' Inspector Jamison stands in for Holmes' Inspector Lestrade - et al. Each has a group of "Irregulars" who assist him in scouring the labyrinthine warrens of Old London Town ...

There are, however, significant differences as well. The Pons stories are set in the 1920s and 30s, starting just after the First World War. The Holmes stories are set some forty years earlier, in the twilight years of the Victorian era (with one significant flash-forward, in "His Last Bow," to a spot of espionage during WWI). Pons frequently mentions his "great predecessor," and even comments on the resemblance of some investigation or another to one conducted by Holmes himself.

Nor are the other characters precisely interchangeable. Dr. Parker is a far more peevish and irritable companion than Watson, and there is far less sniping at the official police in the Pons adventures. Nor is Mrs. Johnson's sang-froid at the goings-on of her unusual tenant nearly as tenuous as Mrs. Hudson's.

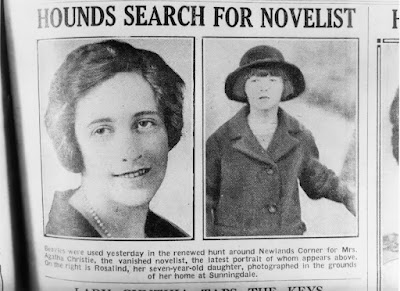

Pons lives in a rather more cushioned fantasy world than his progenitor Holmes. He also encounters other heroes of the time, such as Sax Rohmer's Dr. Fu Manchu, Agatha Christie's Poirot, Somerset Maugham's Ashenden, and even Leslie Carteris's Saint on various occasions, which might have the deleterious effect of breaking the fourth wall, but which nevertheless provides innocent amusement to fans such as myself.

But are the stories themselves any good? Well, that's debatable. They're surprisingly readable. Pons is seldom at a loss when it comes to solving the neat little puzzles that present themselves to him (more often than not by an attractive young lady who "instinctively" addresses herself to him despite the presence in the room of the gloomy Dr. Parker). He often repeats classical Holmesian adages such as "the game's afoot", and is seldom seen without a deerstalker - an item of clothing invented by Doyle's illustrators rather than by the author.

Here's a list of Derleth's original collections:

- "In Re: Sherlock Holmes": The Adventures of Solar Pons (1945)

- The Memoirs of Solar Pons (1951)

- The Return of Solar Pons (1958)

- The Reminiscences of Solar Pons (1961)

- The Casebook of Solar Pons (1965)

- A Praed Street Dossier (1968)

- Mr. Fairlie's Final Journey (1968)

- The Chronicles of Solar Pons (1973)

The story doesn't finish there, though - not by a long chalk. After Derleth's death in 1971, the character was revived by British horror and detective writer Basil Copper (author of Necropolis, among many other titles). He went on to write a further eight volumes of Solar Pons adventures, initially with the cooperation of Derleth's estate, but later on his own:

- The Dossier of Solar Pons (1979)

- The Further Adventures of Solar Pons (1979)

- The Secret Files of Solar Pons (1979)

- The Uncollected Cases of Solar Pons (1979)

- The Exploits of Solar Pons (1993)

- The Recollections of Solar Pons (1995)

- Solar Pons Versus The Devil’s Claw (2004)

- Solar Pons: The Final Cases (2005)

As a result, The Original Text Solar Pons Omnibus Edition was published in 2000 by Mycroft & Moran. It restores the original text as it was before Basil Copper's edits, and includes - as well as the six collections and one novel in order, the full text of A Praed Street Dossier (1968), as well as The Final Adventures of Solar Pons (1998).

To the 71 canonical stories by Derleth included in the 1982 Solar Pons Omnibus, then, one should add the following supplementary publications:

- The Unpublished Solar Pons (1994)

- The Final Adventures of Solar Pons (1998)

- The Dragnet Solar Pons et al.: Original Pulp Magazine and Manuscript Versions (2011)

- The Novels of Solar Pons: Terror Over London and Mr. Fairlie's Final Journey (2018)

- The Apocrypha of Solar Pons (2018)

- The Arrival of Solar Pons: Early Manuscripts and Pulp Magazine Appearances of the Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street (2023)

So what is one to conclude from all this? That some people have far too much time on their hands? That the idea of fan fiction goes back far further in time than one might have supposed (as far back as Cervantes in the 17th century, at least ...) That the Transatlantic battles between American Sherlockians and English Holmesians now have their echo in the battle between these two warring omnibuses? (Or is the correct term omnibi? Basil Copper would know ...)

If you're curious to know more about Solar Pons and his adventures, I strongly recommend the website http://solarpons.com/, which is solely devoted to him. Its creator, Bob Byrne, who is clearly a pop culture fanatic after my own heart, has also written a good introductory article, "The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Meet Solar Pons" (17/11/2014), on his blog Black Gate: Adventures in Fantasy Literature.

I certainly don't regret purchasing Basil Copper's handsomely bound and curated collection of the Solar Pons mysteries - not to mention the many happy hours I've spent poring over its contents. There are only 60 actual Holmes stories to read and re-read, after all, and even a somewhat watered-down version of his mythos such as this can be very entertaining.

I'm also trying very hard to tell myself that I don't need the (even rarer) Original Text Solar Pons Omnibus Edition, but if anyone has a copy for sale at a reasonable price, you could do worse than drop me a line in the comments section below ... There's no fool like a bibliophile, as the saying has it, and I have to plead guilty to the imputation.

•