I must have read Hershel Parker's great biography of Herman Melville sometime in 2005. It's hard to be more precise than that, but the details about Melville's unpublished (and now lost) eighth novel I used in my own short story "The Isle of the Cross" certainly came from there.

That story first saw the light of day in Myth of the 21st Century: An Anthology of New Fiction, co-edited by Tina Shaw and me. That's the only reason I can be so precise.

In those days I used to spend lots of time haunting the stacks in the Auckland Public Library. The extensive collection of graphic novels they kept on the ground floor was always beguiling, but for anything more weighty one generally had to fill in a little card and have it hoisted up from the off-limits basement below.

I don't recall if Parker's two immense volumes were kept down there, but I hope not. They were, after all, only a few years old at that point.

Hershel Parker: Herman Melville: A Biography. Vol. 1, 1819-1851 (1996)

[Cover image by Maurice Sendak]

When I mentioned the treasure trove of information in these books to a prominent Melvillean of my acquaintance, I was rather taken aback to receive a belittling reply. A few pages by a real critic, such as Tony Tanner, he informed me, were worth reams of such stupefyingly immersive material.

Hershel Parker: Herman Melville: A Biography. Vol. 2, 1851-1891 (2002)

[Cover image by Maurice Sendak]

I suppose that that was my first intimation that all was not well in the flowery fields of Melville biography - or criticism, for that matter. Clearly there were at least two schools of thought on the matter.

My own rule of thumb (for what it's worth), is always to award the plum to the critic or editor who seems most disposed to provide me with what the great Grady Tripp in Wonder Boys calls my "drug of choice": new printed material.

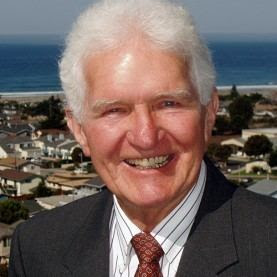

Hershel Parker certainly comes up trumps in that department. As well as his immense biography, he's also largely responsible for a whole series of Melvillean volumes in the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's complete works, the Norton Critical Editions series, and the Library of America (you can see some pictures of the more prominent examples here, if you wish).

It will therefore come as no surprise to you that when I first saw his subsequent book Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative advertised online, I felt extremely curious to read it. At that point I'd made a good resolution to try to read more books from libraries instead of buying them as soon as I saw them, so I duly ordered it for the Massey University Library.

They wouldn't get it for me! The process of listing books and having them acquired for my delectation had worked quite flawlessly up until then. A new policy of denying Academics the books they needed must have come in, however, and I can't recall them buying anything I've asked for from that day to this!

Anyway, to make a long story short, the other day I cracked and finally ordered all three books from Amazon.com. Their service had been pretty lousy over lockdown, but they seem to be making up for it now: the books were all with me in two shakes of a lamb's tail. Hence the title of this piece. I've finally succeeded in reading Hershel Parker's book, after almost a decade of waiting, and am busting to tell the rest of you all about it.

But first, a slight digression. I've always had a lot of time for cranky, obsessive scholars who go a bit strange from excessive concentration on their subject, and who gradually develop a sense of grievance at the world's indifference to their work - not to mention the rewards lavished on other, lesser researchers in the same field. Who do I have in mind?

Well, obviously, Sir Richard Francis Burton (you can find more information about him at the link here). On pp. 387-500 of the final volume of his massive translation of the 1001 Nights, he includes a section called 'The Reviewers Review'd.' This is how I described it in an earlier post on this blog:

In one of the six “Supplemental” volumes to his infamous ten-volume translation of the Arabian Nights (1885-88), Richard Burton included a section called “The Reviewers Review’d,” in which he heaped scorn and contumely on various imprudent critics who’d thought to question his command of Arabic. It’s very amusing to read, though occasionally a little unedifying (in another part of the same volume he put in a long essay abusing Oxford’s Bodleian Library, who’d dared to deny him their copy of the famous Wortley-Montague ms. of the Nights – he’d had to employ someone to make primitive photocopies, or “sun pictures,” of it instead. If they had agreed to lend it to him, he crowed, he would have felt honour-bound to suppress some of the more explicit passages, but since he’d had to pay for the pages out of his own pocket, he’d felt at liberty to spell out every last unsavoury detail for the delectation of his readers!)Yes, that's the attitude, all right. No wonder his employers, the British Foreign Office, exiled him to the backwater of Trieste in the (vain) hope of keeping him out of trouble. What is it they called him? "Brilliant but unsound." One would have to admit that he's had the last laugh in the eyes of posterity, though.

My next exhibit is the prodigiously energetic Sunand Tryambak Joshi (1958- ), otherwise known as S. T. Joshi. Like Hershel Parker, he is both editor and biographer, and his work on - in particular - H. P. Lovecraft has definitely revolutionised the field.

Joshi's self-appointed, life-long task has been to tidy up Lovecraft's literary legacy by re-editing his works (not just the fiction, but the essays and poetry as well), as well as chronicling various other aspects of this activities. This resulted, initially, in the lengthy H. P. Lovecraft: A Life (1996), subsequently re-issued in its even longer original form, in two large volumes, as I am Providence.

Does Lovecraft really deserve all this effort? Well, you're talking to the wrong person, I'm afraid. I accept that his prose is clunky and overblown, his plots predictable, and his racial and cultural attitudes pernicious - but I can't help finding him fascinating even so. The same appears to be true for Joshi, who - as an Asian American - can hardly relish all Lovecraft's diatribes about the 'mongrel races' thronging the Eastern seaboard ...

Joshi, to do him justice, is pretty omnivorous in his taste for Fantastic literature. He's edited editions of Lord Dunsany, Arthur Machen, and Edward Lucas White, among many, many others. He's also written voluminously on Supernatural Fiction in general.

As the title of his book The Stupidity Watch: An Atheist Speaks Out on Religion and Politics (2017), pictured above, would suggest, however, he's also fairly combative when it comes to any belittling of his views - by other, blander, Lovecraftians, for instance. He, too, then, would have to be seen as a prime example of your textbook "irascible scholar".

All of which brings us, by a commodius vicus of recirculation, back to Hershel Parker, the ostensible subject of this post. Who are his particular enemies?

Well, basically anyone who doubts the value of minute archival research on the lives and texts of famous writers is liable to incur his ire: in other words, New Critics, Structuralists, Deconstructionists, and New Historicists (the latter get an extra caning for frivolously pretending to be real researchers without understanding the true rules of the craft). In essence, he's opposed to most of the major trends in American literary-Academic studies since the end of the Second World War.

And, like Burton and Joshi, one has to admit that he makes a strong case. The famous, oft-quoted example of the critic (F. O. Matthiesson) who made a huge to-do over the metaphysical implications of the phrase "soiled fish of the sea" in Melville's White-Jacket, only to end up up with egg on his face when it turned out that Melville actually wrote "coiled", goes a long way to prove his point.

The fact is that, without reliable texts, such hi-faluting scholarship is pretty much of a waste of time. Hence Parker's fifty-odd years of service as co- and eventually managing editor of the 15-volume Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's complete works (1968-2017).

It isn't quite as simple as that, however. Parker has an additional enemy in the famously irritable (and, according to Parker, not particularly competent) textual authority Fredson Bowers. Parker's monograph - jointly authored with Brian Higgins - denouncing Bower's poor choice of copytext for his edition of Stephen Crane's early novel Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (suppressed when it was first written, in the 1970s, and not finally published until 1995, here, down under, in the The Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand) constituted his declaration of war:

However purely he began, Bowers became the Mad Scientist of Textual Editing - a Mad Scientist who ran what may have been the world's sloppiest textual lab and promulgated varying self-serving high-sounding textual theories to cover the slovenliness. [29]In particular, the tedious (and largely pointless) lists of hyphenated words and other trivia in editions of American works of literature promulgated by the Bowers-dominated MLA Center for Scholarly Editions occupied time and space which could more profitably allotted to considering more substantive variants, in Parker's opinion.

When experts disagree, it generally behoves the rest of us to stay silent. It certainly is true that obstrusive over-editing is a feature of many of the scholarly editions produced under the auspices of this organisation.

But then, that's more or less what Edmund Wilson said, in his late essay "The Fruits of the MLA" (1968). And Wilson - or at any rate his army of followers - is another enemy. One of the principal targets of his essay was the then just published first volume in the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's works:

Wilson acknowledged that there was some minimal significance in the textual and historical scholarship. He was even "prepared to acknowledge the competence of Mr. Harrison Hayford, Mr. Hershel Parker, and Mr. G. Thomas Taselle [sic] in the stultifying task assigned them" ... [However,] Wilson's prestige was such that flatterers leapt to endorse his views without ever studying the CEAA editions for themselves. Even thirty and forty years later younger critics justified themselves to their coteries by huddling behind the corpse of Wilson as they lobbed fuzees underhanded toward scholarly editions and biographies. [42-43]Parker concludes:

The CEAA [Center for Editions of American Authors] had been a nobly conceived enterprise but now it was, in fact, flawed, often deeply flawed. Intelligent, constructive criticism, just then, might have worked some good later on. Wilson and [Lewis] Mumford were so extreme as to be merely destructive. [43]

All of which brings us to Public Enemy No. 1, Andrew Delbanco, author of the above biography of Melville, and a vicious critic - in the reviews pages that matter - of Parker's own biography.

In the chapter 'Agenda-driven Reviewers' [pp.167-93 of his book], Parker documents in immense detail the cabal of New York critics and professors who poured scorn on the plethora of new, archivally gleaned facts in his massive work.

Aside from ingratiating himself with the Wilson-revering New York Review of Books crowd, Delbanco had a pretty clear agenda. He could establish himself as an authority on Melville the easy way, not by doing research on Melville, but by reviewing what I published, then what I published next, and then what I published after that. Thereafter, plundering the Higgins-Parker collection of reviews and my two volumes of the biography, he could emerge with a biography of his own, even if he did not get around to learning some basic episodes in Melville's life until after 2002 ... [182]The collective contempt shown by these ignoramuses for the "gigantic leaf-drifts of petty facts" [177] in Parker's first volume went into overdrive when the second volume appeared in 2002:

In the May 20, 2002, Nation Brenda Wineapple (whose vulgar ignorance of Melville and desecration of the Lamb of God I look at elsewhere in this book) declared that I was as secure in my fantasy biography "as Edmund Morris is in his imaginary Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan" ... [Richard H.] Brodhead in the June 23, 2002, New York Times implied that I had invented The Isle of the Cross (1853) and Poems (1860) out of thin air ... In the New Republic (September 30, 2002) the look-ma-no-hands biographer-to-be Andrew Delbanco said I couldn't be trusted at all on anything because I had merely surmised the existence of those lost books [188].Needless to say, Parker (pp.295-300) proceeds to produce oceans of documentary evidence for the existence of these two lost books by Melville. More to the point, though, he quotes the following passage from Delbanco's own biography, written a couple of years later:

When Hawthorne replied, in effect, thanks but no thanks, Melville decided after all to have a crack at the story himself. The result was a novel-length manuscript, now lost [my emphasis - JR], submitted the following spring to Harpers under the title The Isle of the Cross and promptly rejected, possibly because the Harpers anticipated a legal dispute involving descendants of Agatha and her bigamous husband. [301]In other words, precisely what Parker had been saying all along, and a direct contradiction of Delbanco's earlier sneers at the allegedly "merely surmised" existence of this lost book. "Later," Parker goes on, "Delbanco also belatedly recognized the existence of a collection of poems:"

Exactly when Melville started writing verse is unknown, but by the spring of 1860 he had accumulated enough poems to fill a small manuscript, and while in New York waiting to board the Meteor, he asked his brother Allan to place it with a publisher [301].A very belated acknowledgement by Delbanco of his debt to the "prodigious scholarship" of Hershel Parker, "whose discoveries have immeasurably deepened our knowledge of Melville's life" [303] has done little to placate the latter, especially when it turned out that this phrase was entirely absent from the bound-up proofs of Delbanco's biography, which seem to have somehow fallen into Parker's hands.

Need I go on? Like Caesar's Gaul, Parker's book is divided into three parts: an autobiographical opening, outlining his coming-of-age as a Melville scholar; a long denunciation of modern scholarly ignorance; and, finally, a set of fascinating excursions into particular episodes from Melville's life, designed as a kind of supplement to his biography.

Livid with rage at the effrontery of critics who sneer at a book one day and appropriate its findings the next, he finds it difficult to take his foot off the accelerator at times, but it can be justly said that his book is never dull. And while his opponents may be more typically sold-out products of the Academic machine than Parker acknowledges, preferring to type them as fiends incarnate, there seems little doubt that Delbanco and co. did do considerable damage to his scholarly reputation.

Some of his most extreme vitriol is reserved for a comparative bystander, however, the Hawthorne-biographer Brenda Wineapple, whose comparison of Parker's biography with Edmund Morris's notoriously fraudulent Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan I quoted above:

In her review of the second volume of Parker's biography, Wineapple cast back in time to throw doubt on the veracity of the November 1851 meeting between Melville and Hawthorne which served as the culmination of the first volume. A year later, however, in her own biography of Hawthorne, this "fantasy" meeting appears to have become an historical fact:

Early in November, Hawthorne met Melville for dinner at the Lenox hotel, and that night Melville presumably gave Hawthorne his inscribed copy of Moby-Dick, cooked, Melville hinted, partly at Hawthorne's fire. "I have written a wicked book," Melville was to tell him, "and feel spotless as a lamb." [423]"Dirty pool, old man, dirty pool!" as Gomez Addams was wont to say. Wineapple can't really have it both ways. Either it was a fantasy, a complete fabrication from a scholarly fraud, or it was a real meeting, abundantly documented by the kinds of sources Parker has made a speciality of delving into.

Whether Wineapple really merits this much attention is beside the point. She has sinned against the basic tenets of scholarly integrity, sneering in print at a purveyor of facts which she subsequently relied on herself. Parker's denunciations of her "cheeky, vulgar writing" might go a bit far, but he is certainly right to point out that she fundamentally misconstrues the meaning of Melville's "lamb" remark:

Wineapple misquoted what Melville wrote Hawthorne three days or so later, his claiming to "feel spotless as the [not a] lamb." We are dependent on Rose Hawthorne Lathrop's transcription, but this daughter of Hawthorne's knew a biblical reference when she saw one. Melville felt then ... - anyone who knows the Bible or falteringly consults a biblical concordance would have recognized - as spotless as Jesus, the Lamb of God. [424]

As an ex-fundamentalist Christian myself, I must confess it hadn't occurred to me that anyone could miss so obvious a reference, but of course the Bible is no longer obsessively studied by most of the population nowadays. It's not that I think it necessarily should be, but anyone hoping to make a profession of literary criticism had better try to acquire a familiarity with it.

There's scarcely an author in English who doesn't constantly drop in phrases from it from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, a span of approximately five hundred years. And I'm afraid it never really occurred to most of them (including Melville) that these allusions wouldn't be recognised as such.

So, would I recommend that you rush out and buy a copy of Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative, then? Not really - not unless you're a literary biographer or a critic of same. It certainly has an eccentric charm as a book, but one can only salute Parker's wisdom in confining most of this stuff to a single, stand-alone monograph.

His biography will continue to be the one indispensible work on the subject of Melville in English for the foreseeable future, and I guess all his fans continue to await the eventual appearance of his revised edition of Jay Leyda's classic Melville Log.

Parker certainly needed to get all these corrections of fact and emphasis off his chest, but - as is the case with Burton and Joshi (though I doubt the former would relish the comparison) - their true monument remains the splendid works they've managed to usher into the light of day for the rest of us.

•

Hershel Parker: Herman Melville: A Biography (2 vols: 1996 & 2002)

Hershel Parker (1935- ):

His Books in my Collection

-

As Author:

- Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume 1, 1819-1851. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume 2, 1851-1891. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2012.

- Herman Melville. Mardi, and A Voyage Thither. 1849. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker & G. Thomas Tanselle. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 3. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 1970.

- [with Harrison Hayford]. Moby-Dick as Doubloon: Essays and Extracts (1851-1970). A Norton Critical Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1970.

- Herman Melville. The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade. An Authoritative Text / Backgrounds and Sources / Reviews / Criticism / An Annotated Bibliography. 1857. Ed. Hershel Parker. A Norton Critical Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1971.

- Herman Melville. Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land. 1876. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, Hershel Parker & G. Thomas Tanselle. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 12. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 1991.

- Herman Melville. Pierre, or The Ambiguities: The Kraken Edition. 1852. Ed. Hershel Parker. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

- Herman Melville. Published Poems: Battle Pieces; John Marr; Timoleon. 1866, 1888 & 1891. Ed. Robert C. Ryan, Harrison Hayford, Alma MacDougall Reising & G. Thomas Tanselle. Historical Note by Hershel Parker. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 11. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 2009.

- Herman Melville. Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings: Billy Budd, Sailor; Weeds and Wildlings; Parthenope; Uncollected Prose; Uncollected Poetry. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, Robert A. Sandberg & G. Thomas Tanselle. Historical Note by Hershel Parker. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 13. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 2017.

- Herman Melville. Complete Poems: Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War / Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land / John Marr and Other Sailors with Some Sea-Pieces / Timoleon Etc. / Posthumous & Unpublished: Weeds and Wildlings Chiefly, with a Rose or Two / Parthenope / Uncollected Poetry and Prose-and-Verse. 1866, 1876, 1888 & 1891. Library of America Herman Melville Edition, 4. Ed. Hershel Parker. Note on the Texts by Robert A. Sandberg. The Library of America, 320. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2019.

As Editor: