Poetry Workshop

(Saturday 22 April, 9.30 am-12 noon)

el original es infiel a la traducción

[the original is unfaithful to the translation]

– Jorge Luis Borges

Preliminaries

When Michele Leggott asked me to write a short report on the poetry workshop we did at the Bluff 06 Poetry Symposium a couple of months ago, I agreed blithely enough. It’s been hanging over me ever since as a kind of uncompleted obligation. Nevertheless, it’s worth remembering that nothing in the literary field is ever really complete until you’ve written a spiel pointing out what an unqualified success it was – or, rather (as one might say), the proof of the pudding is in the assertion.

So I’m sitting in my office here at Massey Albany, staring at a pile of scribbled-on pieces of paper: annotated interlinear translations, ballpoint drafts of poems, battered sheets of A3 with curious designs drawn on them in multi-coloured felt-tip … I bundled them all together at the end of the exercise (I almost wrote “class”), and have hardly had a moment to go through these rather inscrutable relics since.

The original plan, I must confess, was simply to get the assembled poets to produce some creative transcriptions of foreign-language poems with the help of annotated cribs. Extensive discussions with Michele, however, modified and broadened the idea significantly. “Why not translate out of English as well?” she asked, and I had to admit she had a point.

Why privilege English as a kind of conceptual default? Even if we haven’t been intending to stay on the Te Rau Aroha Marae, the multicultural complexion of our projected line-up of poets would no doubt have brought the issue to the fore.

The request we finally sent out to all the guests at the symposium was accordingly for English-language poems as well as dual-text interlinears:

In the tradition of the collective poem and online anthology put together during FUGACITY 05 in Christchurch, you are invited to attend and contribute to the opening workshop of the BLUFF 06 symposium.

Components

There are various components to the exercise we’ll be doing. The first two are:

- a poem in a language other than English, with interlinear literal translation and notes.

- an anonymous poem in English.

For the rest, you’ll have to wait and see. Please bring along pen, paper and anyone else you think might like to spend the morning writing and talking.

Results

The end result, by Saturday noon, should be one or more poster-poems for display and impromptu reading. After due consideration, you may wish to type up your poem to be posted to the nzepc online anthology being launched next day in Oban, at the final reading of the symposium.

How can you help?

You can send us a poem.

Either one of your own, in which case you would have to agree to allow other people to play variations on it.

Or, alternatively, those of you who are fluent in – or have studied – another language (or languages) could email me a poem laid out as an interlinear text, with the original above and an English translation under each line (as in the example below). Footnotes on contentious points, double-entendres etc. would also be helpful. Please provide a phonetic transcript if it’s written in a non-Roman script.

What kinds of poem should you choose? Well, up to you. Fairly short ones, up to a page in length. Poems which interest you, or which you find challenging in some way.

The greater the variety, the more entertaining the workshop will be.

I made a few comments about it on the

Leaf Salon website, but here goes with a much fuller report:

The Day of the WorkshopSaturday morning dawned grey and overcast, the perfect weather for a good long writing session. I’d brought down enough poems for (I hoped) ten or twelve groups, but a number of people approached me with new materials there in Bluff, so I ended up with enough pieces of paper for an army.

(Poor

David Howard was kept very busy ferrying poems to and from the photocopier;

Martin Edmond and I had had an interesting time the day before trying to find poster-sized paper in Invercargill).

We ended up with seven groups. Each one was issued with a

poem, an interlinear

translation, and a

stimulus (we’d brainstormed these on the blackboard before the exercise got underway):

o Ancestors

o Bluff

o Oysters

o Ferry to Rakiura

o The view out of the window

o The weather

o 100 years from now

I debated for a long time whether or not to post the original materials on this site, but I can’t really see any harm in it. Some of the adaptations were extremely subtle, and it’s hard to get their full flavour unless you know the ingredients each group started from:

Group 1Letter to a lost friendParticipants:

Rob Allan, Michael Harlow, Cilla McQueen, Emma Neale

Original Poem:

The Mooring of Starting OutWe walk into what we’ve made already:

Zapiski

iz podpol’ya – underground; red spot on the right cheek,

then the left, flecked off. More spacious gestures,

opening to wide boulevards, the cars (Daihatsu, Hyundai),

Nikkei index – minutiae of day.

The renovations here fall into legend; we plot their progress,

waiting, day by day.

Dürer’s self-portrait in the Prado: “

Can self-love

go any further?” intones canned Kenneth Clark. Self-loathing,

rather – through the frame dry summer, Central

Otago moon-landscape – six huhus rubbing together.

A lake though, not these bomb-craters of metal,

light-blue and red t-shirt over hipster slacks, skewed platforms.

One more line completes it,

your breasts rhyme with the cloudlessness of day.

[Jack Ross]

Transcription from Chinese:Yang Lian

Berlin Storkwinkel 12 [word for word rendering by Hilary Chung]

Group 2

Nevada’s dead white face Participants:

Jeanne Bernhardt, Martin Edmond, Jeffrey Paparoa Holman

Original Poem:

Some More of Your Friends from NevadaIn a corner of the old Capitol cinema

Balmoral

(Now an indoor rock-climbing centre

track-suited, trussed-up straight arrows

working their way up the walls)

they’ve left up one poster

Wes Craven’s

The Hills Have Eyesa black cut-out hillside (you guessed it)

studded with lidless red eyes

Of course it’s too late to convince you

it’s always that friend of a friend

Who hoons off downriver

veers off the state highway

ends up getting fucked like a pig

or mown into road-spoil?

[Lorraine West]

Translation from Latin:Theodorich of Saint-Trond, near Liege (12th century)‘Flete, canes, si flere vacat, si flere valetis;

Weep, dogs, if there is time to weep, if it suits you to weep;

flete, canes: catulus mortuus est Pitulus.’

Weep, dogs: the little puppy is dead, Pitulus.’

‘Mortuus est Pitulus? Pitulus quis?’ ‘Plus cane dignus.’

‘Pitulus is dead? Which Pitulus?’ ‘More worthy than a dog.’

‘Quis Pitulus?’ ‘Domini cura dolorque sui.

‘Which Pitulus?’ ‘The love and sorrow of his Master.

Non canis Albanus, nec erat canis ille Molossus

Not an Albanian dog, nor was he a Molossian dog

sed canis exiguus, sed brevis et catulus.

but a tiny dog, but short and a puppy.

Quinquennis fuerat; si bis foret ille decennis,

He had been five years old; if he had been twice, ten years old ,

usque putes catulum, cum videas, modicum.

when you saw him, you’d think he was just a tiny puppy. .

Muri pannonico vix aequus corpore toto

Scarcely equal to a marmot with his whole body

qui non tam muri quam similis lepori.

not so much like a mouse as a hare.

Albicolor nigris facies gemmabat ocellis.’

His white coloured face was jewelled with little black eyes.

Unde genus?’ ‘Mater Fresia, Freso pater.’

‘From whence his tribe?’ ‘Mother Fresian, father Fresian.’‘Quae vires?’ ‘Parvae, satis illo corpore dignae,

‘What strength?’ ‘Little, enough to match that body,ingentes animi robore dissimili.’

huge spirits with dissimilar physical strength.

‘Quid fuit officium? Numquid fuit utile vel non?’

‘What was his work? Was it anything useful or not?’

‘Ut parvum magnus diligeret dominus.

‘So that the big master might take delight in the small. ’Hoc fuit officum, domino praeludere tantum.’

This was his work, only to play around for his master.

‘Quae fuit utilitas?’ ‘Non nisi risu erat.’

‘What was the use?’ ‘There was none unless by laughter.’

‘Qualis eras, dilecte canis, ridende, dolende,

Such you were, beloved dog, to be laughed at, to be mourned,

risus eras vivens, mortuus ecce dolor.

living you were laughter, dead behold grief

Quisquis te vidit, quisquis te novit, amavit

Whoever saw you, whoever knew you, lovedet dolet exitio nunc, miserando, tuo.

and laments your death now, which must be mourned.[trans. Bernadette Hall]

Group 3

Trafiggere Participants:

Brian Flaherty, Lisa Williams

Original Poem:

1918

At the edge of Temuka the road is blocked by three bales of hay, a black flag, and the last two O’Shaughnessy kids, who take turns holding the rifle their cousin brought back from the Somme. Outsiders get sent back to the city: Maoris have to keep to Arowhenua, on the far side of the creek we dive in to wash the sickness away.

When Queenie got the cramps we took her to the small house behind the marae, and laid her out on a clean sheet, and fetched a bucket of creekwater, and cooled her stomach and hips, and washed the mushrooms under her arms. The younger kids giggled beside the bed, expecting another baby cousin. First her fingernails then her hands turned black; her breasts swelled, popped their nipples, and dribbled blue-black milk. We couldn’t straighten her arms in the coffin, so we folded them across her chest. She looked like she was diving into herself.

[Scott Hamilton]

Translation from Italian:

Salvatore Quasimodo

Ed è subito sera

And it’s suddenly eveningOgnuno sta solo sul cuor della terra

Everyone is alone on the heart of the earthTraffitto da un raggio di sole:

Transfixed by a sunbeam:

Ed è subito sera.

And it’s suddenly evening.Notes:

the verb ‘trafiggere’ means to run through, stab or pierce – here I’ve gone for the sonic equivalence of ‘transfix.’

‘raggio’ means ‘ray’ – I’ve gone for ‘sunbeam’ for the assonance / slant rhyme it offers with evening, specifically because Quasimodo’s original has the significant full rhyme of ‘sera’ and ‘terra’, as well as the internal half rhyme of sole and solo.

[trans. Cliff Fell]

Group 4“rhapsodia autographia”Participants:

Maureen Dillon, Murray Edmond, Bernadette Hall

Original Poem:

New Leaf

for Alan and MiriamSuch a green song

so full of light sings

in the palm of your

hand, cave walls

have it, the first high-

five to say hello:

that shout of green,

love you could go

crazy for, and all

mind’s tendernesse

to the heart, take hold

[Michael Harlow]

Translation from Russian:Osip Emilyevich Mandelshtam

Za gryemuchuyu doblyest’For the sake of the resonant …

Za gryemuchuyu doblyest’ gryadushchikh vyekov,

For the sake of the resonant valor of ages to come,

Za v’isokoye plyemya lyudyei

for the sake of a high race of men,

Ya lishilsya i chashi na pirye otsov,

I forfeited a bowl at my fathers’ feast,

I vyesyel’ya i chesti svoyei.

and merriment, and my honor.

Mnye na plyechi kidayetsya vyek-volkodav,

On my shoulders there pounces the wolfhound age,

No nye volk ya po krovi svoyei,

but no wolf by blood am I;

Zapikhai myenya luchshye, kak shapku, v rukav

better, like a fur cap, thrust me into the sleeveZharkoi shub’i sibirskikh styepyei, –

of the warmly fur-coated Siberian steppes,

Chtob nye vidyet’ ni trusa, ni khlipkoi gryazts’i,

– so that I may not see the coward, the bit of soft muck,

Ni krovav’ikh kostyei b kolyesye,

the bloody bones on the wheel,

Chtob siyali vsyu noch’ golub’iye pyests’i

so that all night the blue-fox furs may blaze

Mnye v svoyei pyervob’itnoi krasye.

for me in their pristine beauty.

Uvyedi myenya v noch’, gdye tyechyet Yenisyei,

Lead me into the night where the Enisey flows,

I sosna do zvyezd’i dostayet,

and the pine reaches up to the star,

Potomu chto nye volk ya po krovi svoyei

because no wolf by blood am I,

I nyepravdoi iskrivlyen moi rot.

and injustice has twisted my mouth.

[trans. Vladimir Nabokov,

Strong Opinions, 1973 (New York: Vintage, 1990) 280-83.]

Group 5

The Moral is the Swan Participants:

John Dolan, Talia Smith, Robert Cooke

Original Poem:

Pong

between classes I play this computer game called Radial Pong

originally there was Pong

which was just a square with two rackets on either side and a ball going between them

Radial Pong is the same concept in a circle

the rackets are curved like brackets

it takes a bit of getting used to working in this way

because the ball goes off at all these wacky angles

when I’m teaching my students are always looking at their digital dictionaries

or compact mirrors or out the window

so I’m always trying to intercept their line of vision

like I’m playing Radial Pong

it’s a funny job teaching

you have to become a kind of all-pervasive presence

darting around the classroom

breaking them up

raising your voice

you’re not really real

you’re a hologram

they call you Teacher

[Gabriel White]

Translation from French:

Un Gâteau BilangueLes mufliers me rappellent l'Américain

The snapdragons remind me of the American

qui s'est approché de moi dans un café

who came up to me once in a coffee bar

en s'exclamant d'une voix forte,

exclaiming loudly,

– Madame, vous mangez comme un serpent!

– You eat like a snake!

J'ai posé mon gâteau.

I put down my cake

– Pardon, Monsieur?

– I beg your pardon?

– Un serpent. Vous qui êtes tellement petite!

– A snake. And you're so small!

C'était vrai.

It was true.

La tranche avait été grande –

The slice was very tall,

il a fallu ouvrir très grand la bouche pour l'accommoder –

I had to open wide to get it in.

il a fallu faire sortir presque tout à fait les mâchoires des gonds.

Unhinge my jaws.

Et moi avec de la crème au menton,

Cream on my chin,

j'avais été absente, invisible,

I had been oblivious of my surroundings,

sur une planète inconnue.

invisible, on a foreign planet.

[from

Firepenny ©Cilla McQueen]

Group 6net a little to land... Participants:

Hilary Chung, Jacob Edmond, Cliff Fell, Paula Green

Original Poem:

Micromelismata

[Michele Leggott,

DIA (Auckland: AUP, 1994) 7].

Transcription from Chinese:Bei Dao

Shēng huó

Life (two characters: “to be born” and “live”)

网

wang = net, network, web (including www web)

one character-looks like a net: 网

[word for word rendering by Jacob Edmond]

Group 7

gyres of moaning poppies Participants:

Michele Leggott, Jack Ross, Helen Sword

Original Poem:

from A Satire Against Reason and MankindThe senses are too gross; and he'll contrive

A sixth, to contradict the other five;

And before certain instinct will prefer

Reason, which fifty times for one does err.

Reason, an ignis fatuus of the mind,

Which leaving light of nature, sense, behind,

Pathless and dangerous wandering ways it takes,

Through error's fenny bogs and thorny brakes;

Whilst the misguided follower climbs with pain

Mountains of whimseys, heaped in his own brain;

Stumbling from thought to thought, falls headlong down,

Into doubt's boundless sea where, like to drown,

Books bear him up awhile, and make him try

To swim with bladders of philosophy;

In hopes still to o'ertake the escaping light;

The vapour dances, in his dancing sight,

Till spent, it leaves him to eternal night.

Then old age and experience, hand in hand,

Lead him to death, make him to understand,

After a search so painful, and so long,

That all his life he has been in the wrong.

Huddled in dirt the reasoning engine lies,

Who was so proud, so witty, and so wise.

[Henry Wilmot, Lord Rochester]

Translation from German:Rainer Maria Rilke

Sonette an Orpheus – I, ixSonnets to OrpheusNur wer die Leier schon hob

Only [he] who the Lyre already raisedauch unter Schatten,

even among shades,darf das unendliche Lob

may the infinite Praise,

ahnend erstatten.

when sensed, render.

Nur wer mit Toten vom Mohn

Only [he] who with the dead of poppiesaß, von dem ihren,

ate, those which were theirs,

wird nicht den leisesten Ton

will not the softest notewieder verlieren.

again lose.

Mag auch die Spieglung im Teich

Though even the reflection in the pond may

oft uns erschwimmen:

often dissolve before us:

Wisse das Bild.

Know the image.

Erst in dem Doppelbereich

Only in the dual realm

werden die Stimmen

will the voices

ewig und mild.

be eternal and gentle[from

The Penguin Book of Twentieth-Century German Verse, ed. Patrick Bridgwater, 1963 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968) 47].

Conclusions

I guess, from my point of view, the most interesting thing was that each of the seven groups took a completely different tack on what they were “supposed” to do. It would have been a bit odd if such a stellar group of talents

hadn’t come up with some pretty interesting poems, but I hadn’t expected quite such a range in the results:

- Group 1 composed a gentle, allusive lyric.

- Group 2 wrote a stanza each (Martin the first, Jeffrey the second, Jeanne the third, if you’re curious).

- Group 3 chose to emphasise the clash of languages.

- Group 4 condensed their materials with Zukofskyan precision.

- Group 5 ended up transcribing the vagaries of their own writing process.

- Group 6 made a concrete poem.

- In Group 7, breaking down the wordy materials we’d been given into bite-sized phrases inspired us to make a kind of collage – which doubled as a reading score.

I suppose the real point of this postmortem on our poetry workshop is to suggest that poetry is a more robust art than even poets often assume. Once you’ve chanced upon something interesting, something from left field, by going along with an exercise like this, I hope you’ll feel more inclined to get wiggy with it more often in the rest of your writing.

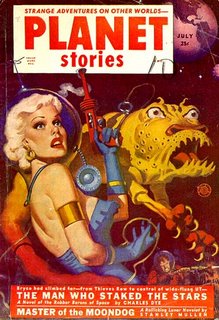

Planet Stories (July 1952) -- Philip K. Dick's first published story, "Beyond Lies the Wub" appeared in this issue (though it isn't mentioned on the cover ... I take it that lobster thing is meant to be a moondog rather than a wub).

Planet Stories (July 1952) -- Philip K. Dick's first published story, "Beyond Lies the Wub" appeared in this issue (though it isn't mentioned on the cover ... I take it that lobster thing is meant to be a moondog rather than a wub).