Should you ever have occasion to look up the name of Henry Torrens on Wikipedia, you may have some difficulty actually locating him. You'll find Major-General Sir Henry Torrens KCB, author of that standard textbook Field Exercise and Evolutions of the Army (1824):

Chances are you'll also find his grandson, the even more eminent Lieutenant General Sir Henry D'Oyley Torrens KCB KCMG, without too much trouble:

What you won't find, unless you look very hard indeed, is the entry on Henry Whitelock Torrens, son of the first, and father of the second of the military gentlemen listed above:

Henry Whitelock Torrens (20 May 1806 – 16 August 1852), son of Major-General Henry Torrens, was born on 20 May 1806. He received his B.A. at Christ Church, Oxford (where he was a president of the United Debating Society), and entered the Inner Temple. After a short service under the Foreign Office, he obtained a writership from the Court of Directors of the East India Company and arrived in India in November 1828 and held various appointments at Meerut. In 1835 he joined the Secretariat, in which he served in several departments under Sir William Hay Macnaghten. In 1839 he assisted in the editing of the Calcutta Star, a weekly paper, which became a daily paper called the Eastern Star. He was secretary (1840–1846) and a Vice-President (1843–1845) to the Asiatic Society of Bengal (now the Asiatic Society). In December 1846, he was appointed Agent to the Governor-General at Murshidabad. Here in his endeavours to improve the Nizamat administration, his relations with the Nawab Nizam and his officials became greatly strained.A bit of a nobody, one might feel tempted to conclude: a lawyer and journalist, who died young, leaving behind a son and a pile of "scattered papers."

He was a clever essayist as well as a journalist and scholar, and his scattered papers were deservedly collected and published at Calcutta in 1854.

Torrens died of dysentery at Calcutta while on a visit to the Governor-General on 16 August 1852 and was buried in the Lower Circular Road Cemetery.

What this entry fails to mention, however, is his importance as the author of the first serious attempt at a complete English translation of the 1001 Nights from the Arabic. He is included on the page devoted to Translations of One Thousand and One Nights, however:

Henry Torrens translated the first fifty nights from Calcutta II, which were published in 1838. Having heard that Edward William Lane began his own translation, Torrens abandoned his work.

There's a bit more to it than that, however. Luckily Richard Burton, in the preface to his own complete 1885 translation of the collection, is somewhat more expansive:

At length in 1838, Mr. Henry Torrens, B.A., Irishman, lawyer ("of the Inner Temple") and Bengal Civilian, took a step in the right direction; and began to translate, "The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night," (1 vol., 8vo, Calcutta: W. Thacker and Co.) from the Arabic of the Ægyptian (!) MS. edited by Mr. (afterwards Sir) William H. Macnaghten. The attempt, or rather the intention, was highly creditable; the copy was carefully moulded upon the model and offered the best example of the verbatim et literatim style. But the plucky author knew little of Arabic, and least of what is most wanted, the dialect of Egypt and Syria. His prose is so conscientious as to offer up spirit at the shrine of letter; and his verse, always whimsical, has at times a manner of Hibernian whoop which is comical when it should be pathetic. Lastly he printed only one volume of a series which completed would have contained nine or ten.You'll note that his wikipedia entry above made no mention of Torrens' Irish antecedents. Burton's remarks about the "Hibernian whoop" in his verses underlines it rather patronisingly ("plucky" seems a rather belitting epithet to apply to a fellow author, also). The curious thing is that Burton himself was often discriminated against as an Irishman by his intensely class and caste-conscious English contemporaries. Whilst he himself was born in Torquay, both of his parents were of Irish extraction.

- Richard F. Burton, "The Translator's Foreword." A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments, Now Entituled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, 10 vols. Benares: Kamashastra Society, 1885. vol.1: xi.

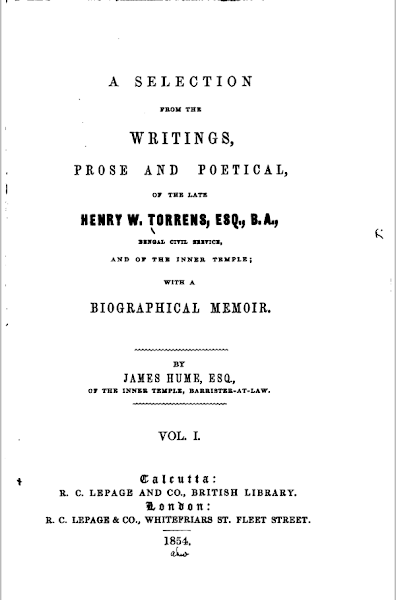

Anyway, whatever the rights and wrongs of the case, here are the title-pages of Torrens' two principal publications. Fortunately both are readily available online as free e-texts:

- Torrens, Henry. The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night: From the Arabic of the Aegyptian Ms. as edited by Wm Hay Macnaghten, Esqr., Done into English by Henry W. Torrens. Calcutta: W. Thacker & Co. / London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1838.

- Hume, James, ed. A Selection from the Writings, Prose and Poetical, of the late Henry W. Torrens, Esq., B.A., Bengal Civi Service, and of the Inner Temple; with a Biographical Memoir. 2 vols. Calcutta & London: R. C. Lepage & Co., 1854.

The editor of the second of these volumes explains that:

I have taken nearly all the poetry from the volume of the Arabian Nights ... because I found selection most difficult where all appeared good. The book is out of print, or nearly so I believe, and the severest critic will not blame me for preserving what otherwise might soon have been lost, or at any rate difficult to procure.So who's correct? Did Torrens have any poetic talent or not? Burton (of course) had a tendency to play down the merits of any possible rivals. He himself has a reputation as a most execrable versifier (unlike his fellow Nights translator, John Payne).

Perhaps, then, you should judge for yourselves:

Then they both gave her rings from off their hands, and she said to them, "This Ufreet carried me off secretly on the night of my marriage, and put me into a coffer, and placed the coffer in a chest, and put on the chest seven strong locks, and laid me low in the midst of the roaring sea, the ever restless in the dashing of waves; yet he does not know that when a woman desires aught, there is nothing can prevail against her, as certain poets say.The passage above comes from the frame-story to the Nights, where the two brothers Shahryar and Shahzaman, having executed their wives for adultery, are riding out to try and discover a virtuous woman. This one, even though she was abducted on her wedding night by a seemingly all-powerful Ifrit, has still managed to cuckold him more than 500 times.

"With confidence no women grace,Certain poets too have said,

Nor trust an oath that's given by them;

Passion's the source and resting place,

Of anger and joy with them;

False love they show with lying face,

But ’neath the cloak all's guile with them;

In Yoosoof's story you may trace,

Some of the treacheries rife in them;

See ye not father Adam's case?

He was driven forth by cause of them.“But alas! for you, who blame me

Fix the blamed one in his fault!

Is the sin with which you shame me,

Great and grievous as you call't?

Say, I be indeed a lover,

Have I done aught greater crime

Than in all men you discover,

Even from the olden time?

Ne'er at earthly thing I'll wonder,

Whatsoe'er the marvel be,

Till on one I chance to blunder

Scaped from woman's wile scot free."

Here's Burton's 1885 version of the same passage:

When they had drawn their two rings from their hands and given them to her, she said to them, "Of a truth this Ifrit bore me off on my bride-night, and put me into a casket and set the casket in a coffer and to the coffer he affixed seven strong padlocks of steel and deposited me on the deep bottom of the sea that raves, dashing and clashing with waves; and guarded me so that I might remain chaste and honest, quotha! that none save himself might have connexion with me. But I have lain under as many of my kind as I please, and this wretched Jinni wotteth not that Destiny may not be averted nor hindered by aught, and that whatso woman willeth the same she fulfilleth however man nilleth. Even so saith one of them:—'Rely not on women;And another saith:—

Trust not to their hearts,

Whose joys and whose sorrows

Are hung to their parts!

Lying love they will swear thee

Whence guile ne'er departs:

Take Yusuf for sample

'Ware sleights and 'ware smarts!

Iblis ousted Adam

(See ye not?) thro' their arts.''Stint thy blame, man! 'Twill drive to a passion without bound;

My fault is not so heavy as fault in it hast found.

If true lover I become, then to me there cometh not

Save what happened unto many in the by-gone stound.

For wonderful is he and right worthy of our praise

Who from wiles of female wits kept him safe and kept him sound.'"

And here's John Payne's (1882):

So each of them took off a ring and gave it to her. And she said to them, "Know that this genie carried me off on my wedding night and laid me in a box and shut the box up in a glass chest, on which he clapped seven strong locks and sank it to the bottom of the roaring stormy sea, knowing not that nothing can hinder a woman, when she desires aught, even as says one of the poets:I rede thee put no Faith in womankind,Or as another says:

Nor trust the oaths they lavish all in vain:

For on the satisfaction of their lusts

Depend alike their love and their disdain.

They proffer lying love, but perfidy

Is all indeed their garments do contain.

Take warning, then, by Joseph's history,

And how a woman sought to do him bane;

And eke thy father Adam, by their fault

To leave the groves of Paradise was fain.Out on yon! blame confirms the blamed one in his way.

My fault is not so great indeed as you would say.

If I'm in love, forsooth, my case is but the same

As that of other men before me, many a day.

For great the wonder were if any man alive

From women and their wiles escape unharmed away!"

So what do you think? I certainly think it would be difficult to claim that Torrens's version was any worse than either of the others. On the contrary, it's much easier to follow, and seems to mean much the same thing. As for Burton's accusation that the former's translation exemplified "the verbatim et literatim style," it's surely the case that both Payne and Burton make far greater efforts to follow the verbal and syntactical oddities of the original Arabic.

No doubt it's true that Torrens gave up on his project when he heard that Edward W. Lane was engaged in a not dissimiar work - not knowing, perhaps, how sadly bowdlerised the resulting translation would turn out to be. There's a curious echo, there, of Burton's discovery, fifty years later, that John Payne was embarked on the same project of a complete and literal translation of The Thousand Nights and One Night.

Unlike Torrens, though, Burton did not choose to step aside meekly. Instead he offered Payne priority of publication, but then went on to issue his own extensively annotated version a year later. The embarrassing similarities between large parts of the two translations has led to accusations of plagiarism on Burton's part. Whether or not this is true, even Burton admitted that when a previous scholar has hit on the perfect way to express something, it would be needless pedantry to insist on phrasing it differently. Make of that what you will.

It does seem possible that Burton was so scornful of Torrens because the latter resembled him in so many ways: the 'un-English' exuberance of manner, the gift for languages ... Unlike Torrens, though, Burton was sent down from Oxford without a degree, and managed to antagonise almost all of his well-wishers both in India and England.

Torrens, by contrast, managed to work harmoniously even with the eminent but eccentric William Hay Macnaghten, whose four-volume edition of the Arabic text of the 1001 Nights - the basis for his own translation - remains a monumental and irreplaceable work.

Of course, to anyone familiar with the history of nineteenth-century India, and particularly the ill-judged 1839 invasion of Afghanistan, Macnaghten is better known as the blundering political officer who was captured and killed by the Afghans in December 1841, shortly before the disastrous retreat from Kabul - generally thought to be among the worst military disasters in British history.

Macnaghten has a cameo role in the section devoted to the Afghanistan debacle in George MacDonald Fraser's irreverent but highly readable pisstake version of imperial history Flashman (1969), which purports to be the memoirs of the bully from Tom Brown's Schooldays.

Interestingly enough, the city I live in, Auckland, is named after George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland, Governor-General of India between 1836 and 1842, whose other great claim to fame is principal responsibility for the Afghanistan disaster.

My father could never walk past the toga'd statue of the great fool - originally erected in Calcutta in 1848, but donated to our city in 1969 - without shaking his fist and calling down curses upon his name.

The connections are all there, once you're ready to see them.